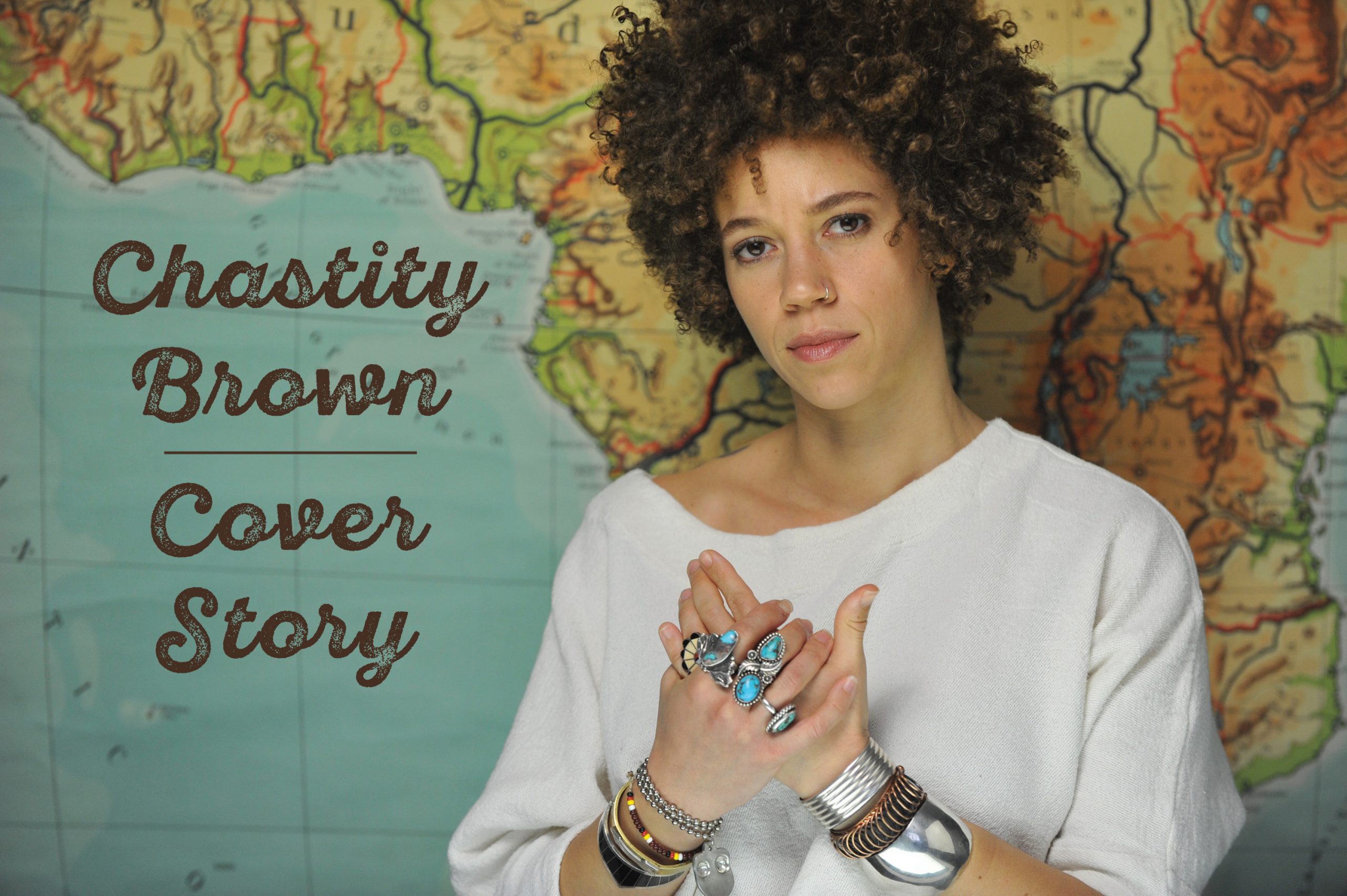

“All my life, I was afraid of everything, and I wouldn’t touch what was beautiful to me,” sings Chastity Brown on “Drive Slow,” the first track on her new LP, Silhouette of Sirens. Appropriately, it’s a song filled with motion: an automotive chug toward the horizon, a call to move on and leave our ashes behind. But, like Brown herself, it’s more complex than just that. There are moments to stop, plant your feet, and savor the stillness, a rearview mirror filled with memories both sweet and sinister.

But Brown likes to move, no doubt — right now, she’s just completed a run in Denver, where she’ll be singing in Ani DiFranco’s back-up band later in the night. She certainly likes to move on, too, and Silhouette of Sirens finds the Minnesota-residing, Tennessee-born artist pondering perseverance: how to overcome and heal a broken heart with an understanding of all the many ways one can be shattered in the first place.

Now signed to Red House Records, Brown crafted Silhouette of Sirens with her longtime writing partner, Robert Mulrennan, and the result is a set of songs that exist in the perfect sweet spot between roots inspiration and modern sensibilities. And with plenty of soul-bearing honesty, too. “I try to find a way to sing where I’m not having a therapy session,” says Brown. “But I think there is a lot of longing on this record.” These aren’t songs to be heard prone on the couch anyway. “Pouring Rain” has a soul-filled groove, and “Carried Away” is a delicate but sweeping mid-tempo ode to rising up and over what sets us adrift.

You just got back from a jog — does running help you think creatively?

It helps me calm down. I think I have such high anxiety that it clears out the cob webs. I don’t do it to be entirely healthy. I just have to have something to take the edge off.

It’s been quite a bit of time since 2012’s Back-Road Highways, your last release. So much has changed since then: You have a new label, you’re five years older, we have a new president. How do you reflect back on it all?

There are mile markers that I think are physical: a record label, for one. I finished the album two years ago and, at that point, I had taken two years to make it. That was the longest I had taken for anything. And, at that time, I was also turning 33. I’m not religious or anything, but I was like, “This is my Jesus Christ year. This is my Buddha year.” Thirty-three is where you go big or go home. And I gave myself permission to actually be ambitious and gave myself permission to get what they call in the music business a “team.” To make the album, I had emotionally gone through a really dark time without realizing it, and that influenced the work. I was separating all the dark shit going on in my head with these songs I was writing with my writing partner. It wasn’t until after I finished that I was like, “Holy shit, this actually digs deep into my subconscious and exercises some demons I wasn’t ready to acknowledge.”

How so?

The music reflected itself back to me and, in one part, let me know I was quite broken, and in another part of the album, let me know I wasn’t that way anymore. It’s a fucking therapy session, but I can’t say what it feels like to be different. Though I know I’m literally in a different place than when I was making it.

Was it difficult to give up your independence and sign to a label?

Yeah, I’m a little bit — and I think my band mates can vouch for the fact that — I am a little bit controlling. But at the same time, this isn’t really possible to do alone. I had to ask people for their gifts and talent. It was difficult to relinquish some of that, but we all work really well together. I’m a 34-year-old woman who is not going to be told what to do. Working with these people on collaboration, I don’t feel like it’s me telling them what to do or the opposite. But I do have clear goals, and it wasn’t just a spur-of-the-moment decision. It was thought out, and I have to trust them. And I do.

You mentioned the album was finished two years ago, so do these songs still feel fresh to you?

I was expecting them to be old by now, but they’re not old to me. Maybe it’s just my relationship with them. For 2016, I got the incredible opportunity to tour with Ani DiFranco, and that was the real test of these songs. And I feel like they can hold their own. I still love them. But after you create, and you go on the road, and you geek out, the songs are still evolving. All I did is capture where these songs were at the time. But now I’ve changed, shit’s changed. They augment with me.

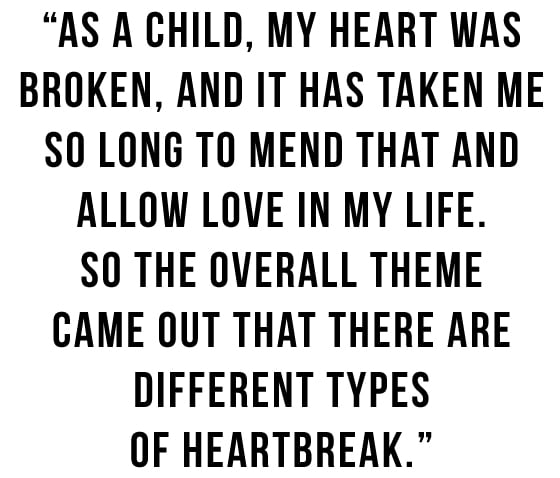

Who were you then versus now?

What I was experiencing during that dark time was having a really dark childhood. I think because of that — and the album is not about that at all — but I feel really sensitive to other people’s stories, and what I had realized is, that time period in my life broke my heart. As a child, my heart was broken, and it has taken me so long to mend that and allow love in my life. So the overall theme came out that there are different types of heartbreak. Of course there are love songs, but there are other things that break your heart. There is more to life than songs about coupled relationships — though I love those — but this is a little bit broader. A macro view of different types of heartbreak informed by my own personal heartbreak.

You’re singing with Ani tonight and you’ve opened for her in the past. That must have been an amazing, informative experience.

Yeah. Shit. I’ve said this before: It’s the most generous thing that any artist has done. She’s showed me how it’s done, in a different way. I’ve been touring for 10 years, but there are different things at her level, which you can only see from there. In the folk world, it’s generational, passing things down. It’s huge to me, how generous she’s been. And it’s a good affirmation that someone I respect gives me a thumbs up.

Did you have conversations with her about what it means to be a politically engaged artist?

Well, I don’t think we talk in terms of what things mean. We were out on the road when Trump was elected president, and what we talked about was how to act, and in what capacity. We have such a privilege, all across the country: When you step on stage, you are the loudest person in the room. I feel like Ani teaches by showing. She stands in her integrity so fiercely, it made me want to articulate even more what matters to me. Like how Black Lives Matter has been a huge cornerstone in what I talk about from stage the past year-and-a-half, and it will be until I feel like folks get it. You’d be surprised how many “liberal” audiences have a rebuttal to that.

Really?

I remember in Utah, I was talking about this Nina Simone song and I said, “I play this because Black lives matter.” And this woman was like, “All lives matter!” I want to use compassion to educate people, but at the same time, God, that woman fucking infuriated me. But it wasn’t the time. Going back to what to do as an artist during these times, it’s to use your voice in the capacity of your life. I’m from Tennessee; I have family members who voted for Trump. And those are family members I love, and I can’t pretend that they are evil. But I can get down and dirty in a difficult conversation, trying to figure out where they are coming from.

Have you written any overtly political songs?

I have, but none that I would play out. One of the titles was like, “Fuck You Pieces of Shit!” An ongoing rant. I was like, maybe I can kind of hone it in! But I have been creating. A lot of people are saying, “What are artists going to say as a comeback to all this?” And I’ve heard some incredible work that’s going after how fucked up our government is, but there are other things to focus on. Like the beauty of being a brown woman and celebrating that. There was a time after so many police shootings, all the songs I was writing were really angry. But Solange [and her 2016 LP, A Seat at the Table] was a great reminder of “Yo, let’s talk about our beauty.” And we should.

Photo credit: Wale Agboola