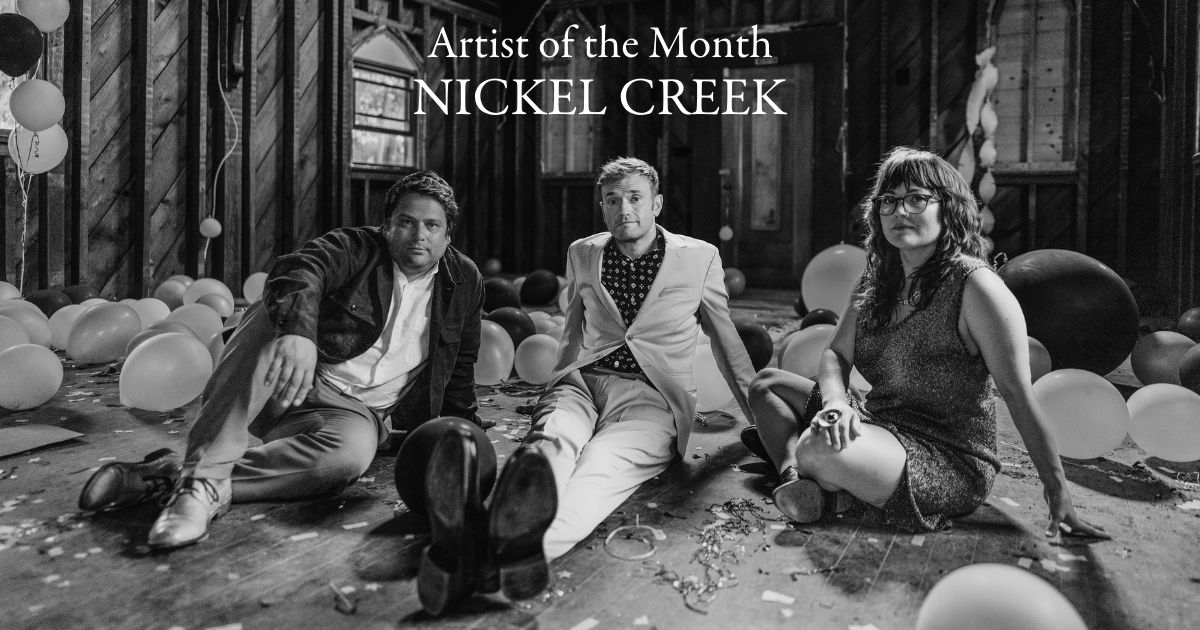

While they may be a foundational band in 21st-century roots music, the members of Nickel Creek have never saddled themselves with that genre’s conservatism. They dream big, viewing folk, bluegrass, and string band music as a launchpad to bigger ideas and heavier, weirder sounds, yet they’ve never been especially prolific as a trio. Since 2005 they’ve released only two albums, which makes Nickel Creek not quite an active band but not quite a side project either. Instead, the three players can return to the fold once a decade or so, whenever it feels right, whenever they need to get something off their chests together. As such, each new album becomes a point by which they can measure how much life has gone by, how they’ve changed as people and as players.

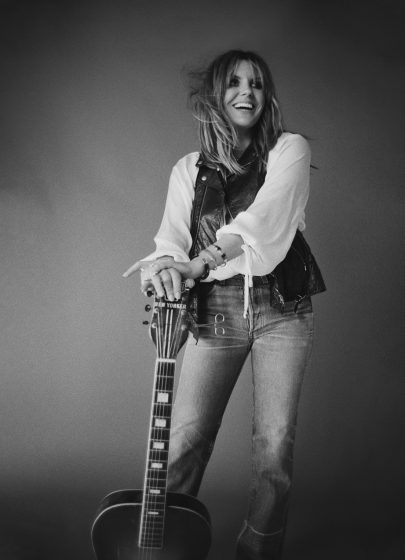

Since they released The Dotted Line back in 2014, fiddler Sara Watkins has been especially busy with an array of projects. She released two excellent solo albums, including 2021’s Under the Pepper Tree, inspired by her own children. She formed the supergroup I’m With Her alongside Sarah Jarosz and Aoife O’Donovan. She has backed artists as varied as Phoebe Bridgers, Robert Earl Keen, Amy Ray, and the Killers. And she and brother Sean founded the Watkins Family Hour, less a band than a live revue featuring Jon Brion, Madison Cunningham, Fiona Apple, and actor John C. Reilly. She brings all of that to bear on Celebrants.

In the first of our series of individual interviews with the members of Nickel Creek, Sara talked to the Bluegrass Situation about getting the band back together, exploring the friction in their relationships, and singing psychedelic cowboy harmonies. Look for our Artist of the Month interviews with Chris Thile and Sean Watkins in the weeks ahead.

BGS: At what point did you realize that it was time to make a new album? Was there a moment when the idea clicked into place for everyone?

Watkins: We always had it in our heads that we were going to do something in the future. We knew there would be more Nickel Creek music that we wanted to make. But it really started when we were asked to get on the phone together to do an interview with NPR. They brought it to our attention that it had been twenty years since our first release on Sugar Hill. We didn’t realize that it had been that long. It was mind-blowing that so much time had passed. We got on the phone together and were reminiscing. It was fun and felt really good. That was the first summer of the pandemic, so it was especially heartwarming to connect with anybody at that point. That started a conversation: Maybe this is our moment to get together and figure out what we want to do and try our best to make it happen. That’s what we did. We spent several months figuring out a way just to be together.

What is your relationship with each other like during those down years between records?

We’re all friends. Of course, Sean and I are siblings. We’ll run into each other often at festivals or gigs or weddings or parties. That’s always lovely. The nature of making a living as a musician is staying busy and touring, and the nature of being a musician is inviting all kinds of different collaborations — different people to play with, different records to make. It’s a testament to the strength of Nickel Creek that we’re each able to do that and not break up because of it. It also adds to the strength of the band in that we become stronger individuals and better musicians because of what we learn from those projects.

As a fiddle player, if I’m only playing Nickel Creek songs, then I’m not going to have anything new to bring to the table after a while. But if I’m in the house band for some big concert or supporting someone on tour or doing solo projects, I can use all of that to say, “What do I want to do right now?” That’s true for Chris and Sean as well. When we do come together, we truly have new things to say to each other. So much life has happened, so let’s bring it in. Let’s work it up. Let’s develop those ideas together. Side projects are really important for this band. It’s a huge part of how we’re able to keep growing.

What can you tell us about the writing and recording sessions? It sounds like you were writing songs, but also writing them as a larger piece of work.

Going into it, we knew we wanted it to be the kind of record that related to itself. We didn’t want it to just be a batch of songs that we put together on an album. We wanted the music to relate to itself. We wanted the songs to transition thoughtfully into each other. We’re writing about seemingly simple things like how to have friends, how to keep them, how to remember to engage with this person that you really care about. These are all topics that can’t be resolved in one song. They often require multiple revisits.

That approach afforded us the opportunity to take a melodic theme from one song and make it the bridge in another song. Or vice versa. We found we could do a similar thing with lyrical themes. It would have been almost impossible if we hadn’t been afforded this big chunk of time to lay the foundation together. We were living in a house together. We were spending almost every minute of every waking hour of every day together — having breakfast, talking about life, discussing music, catching up on what was going on with so-and-so’s cousin that we used to know growing up. Having that kind of time together allowed us to make this kind of record. If we were emailing each other lyrics or even just touching base a couple of times a day, it would’ve been impossible.

How long were you all living together?

Chris’s family drove out from New York, and we all spent two weeks together in a friend’s house in Santa Barbara. Then we spent another two weeks in LA. We weren’t all sleeping under the same roof then, but we were spending all day together. Our kids were getting together, our spouses were meeting each other for the first time, our dogs were all playing together. It was a really lovely and immersive experience. We were living out a lot of the stuff that we were writing and singing about.

That comes through on the opener, “Celebrants,” which is about that kind of reunion and the spaces between people. It really ushers you into this world.

We were thinking about that a lot. We were imagining our first shows for this album. We were talking about how that would feel and how great it would be if the first song on the album represented the way we think we’ll feel in those shows. “God, it’s good to see you!” But I guess we’re also singing it to each other. This is an album about the relationships that we often take for granted. Zooming super far out, it’s about how we feel about ourselves. This is just the stuff life is made of. There’s celebration, but there all those topics that we hope people don’t bring up. There’s all the wonderful stuff, and then there’s the mess. There’s that middle part of relationships that we often skip through. It’s not as sexy as the beginning or as devastating as the end. But it’s the bulk of life. That’s what we wanted to capture.

It also sounds like a way to mark time for you. It’s been nine years since the last Nickel Creek album, and it sounds like making this new one became a way to take in all the life that’s happened since then.

All of that’s absolutely true. We will always remember what was going on in our lives as we were writing this record. We were writing about what we were living, what we were experiencing. And we’re not unique in what we were going through, except in the context of us as a band. I think everybody craves intimacy, but we’re terrified of looking someone we don’t know in the eye. We all have a desire for true connection, but we’re allergic to the idea of friction. That’s where the warmth comes from. Friction. All the things are that true in physics are true emotionally as well. We need each other and we need differing points of view to have any kind of strength, but what’s required is the willingness to sit with that, the willingness to say, “I don’t agree and I’m still here.”

What kinds of conversations were you having about the music? It sounds like such an ambitious record, with an almost psychedelic quality to it.

I’m intrigued by what sounds psychedelic to you. There are some vocal bends that we came up with in the first two weeks, and they really set the tone for a lot of the vocals that we have on the record. The house had some high ceilings, and it was really a dream to sing in those rooms. There’s that moment on “The Meadow” where we’re all singing three-part harmonies, which bend and morph and separate and come back together. We were imagining this moment where everything goes into double vision for a second, then snaps back into clarity. I guess that might come across as psychedelic, but we were patterning it off those Sons of the Pioneers cowboy harmonies that we grew up singing. It was almost nostalgic to us, but also kind of trippy.

And when we all went to Nashville to record, we did take advantage of the studio. That became a surreal element, because the record isn’t meant to sound like a live show. It’s meant to sound like a record. That’s something that Eric Valentine, our producer and engineer, presented to us back when we were making Why Should the Fire Die? almost 20 years ago. He said that the studio isn’t doing its best job if you only use it to get the best live performance. That’s all fine. We’ve done that before, and we can do it again. But there is an opportunity, particularly with someone like Eric, to use it in a different way. Live shows are live shows, but the studio is an opportunity to do something totally different. On a lot of songs you’re hearing string sections that we built up in the studio. Chris played mandolin and mandola. You’re hearing Sean play guitar and baritone guitar and maybe also a high-strung guitar all at once, like on “Goddamned Saint” and “Failure Isn’t Forever” at the end of the record. I think we all played every instrument we had on “Failure Is Forever.” It’s a real curtain call. We were using all the tools we had on hand.

Photo Credit: Josh Goleman