For legions of folks, Wendell Berry is far more than a writer and a farmer. He's also a hero, an icon, a role model. His plain-spoken, yet poetic way of moving through the world inspires those who seek to tread a similarly thoughtful path without leaving much in the way of footprints. Through his book writing and community building, Berry shares his message of heart, of healing, and of hope — a message that filmmaker Laura Dunn set out to capture and convey in her new documentary about Berry, The Seer.

You had an interesting challenge on your hands to paint a portrait of Wendell by sketching out his world and his view without ever filming him. Because his voice is there and his life is there, you almost don't notice that he's not actually there. Mission accomplished?

Yeah, oh yeah. That's great to hear. I've been doing documentary films for a while and I'm tired of the sort of sprawling issues piece. I was interested more in something personal, something intimate. I really wanted to do a portrait. That way you get to know a single person and piece together a bunch of different issues.

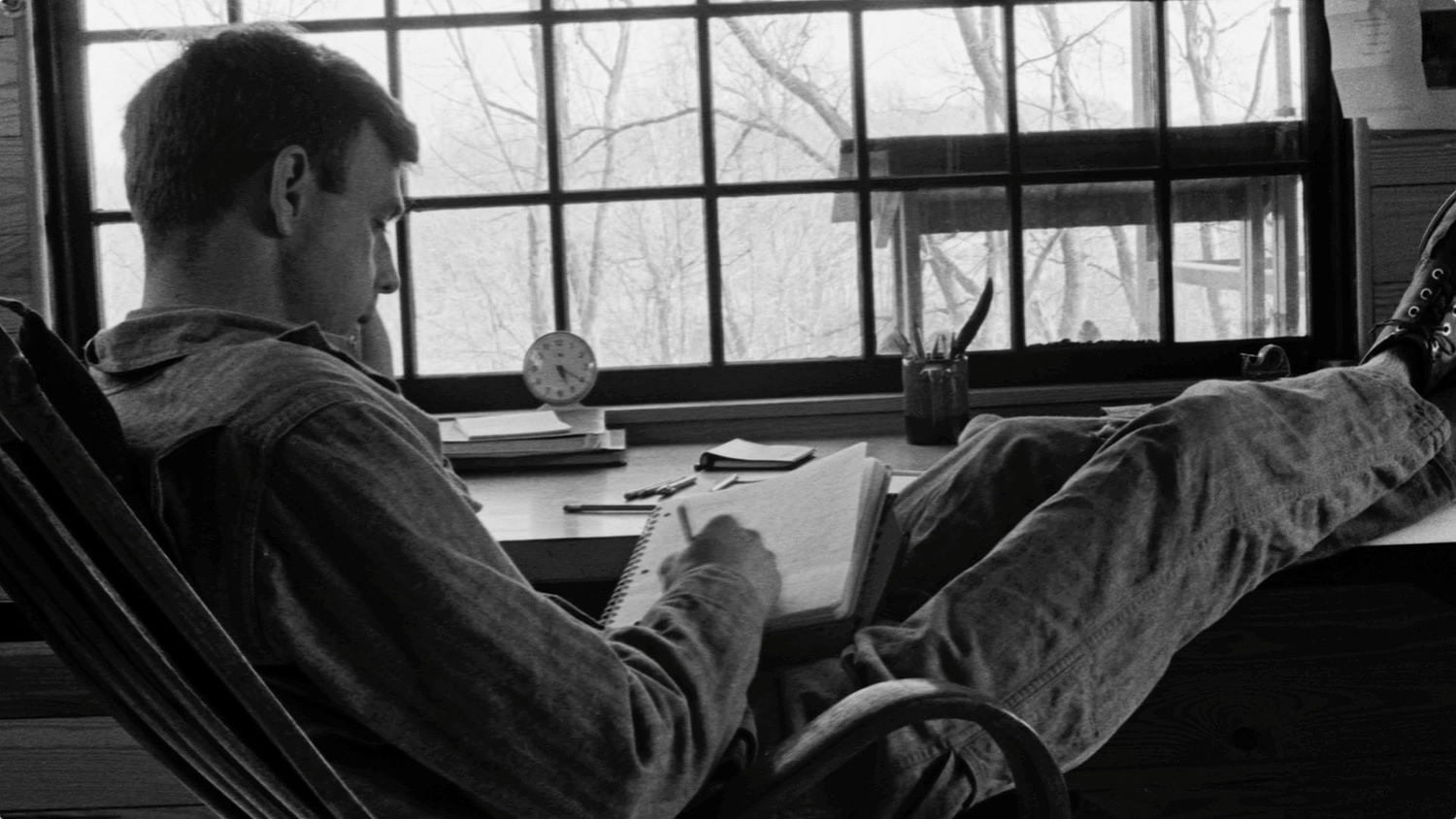

Wendell's my favorite writer — has long been — and I'd met him in the course of working on my last feature. I wanted to do something with his work. So I set out to do it that way, though I knew pretty early on that he was anti-screen, of all kinds. That certainly presents a challenge, but I like that challenge. It might make it less marketable, but that's not why I do films.

I mean, it'd be one thing if he didn't want to go on camera because he's shy or whatever. But his opinion about screens, I think is really interesting and provocative. He thinks they deaden the imagination, that they contribute to the decline in literacy. So I think not having him on screen actually reflects something essential about him, if that makes sense. I thought it was a good challenge because it actually forces you to open up your imagination and think in a different way … which is what Wendell does, through his writing.

Absolutely. The thing that steps up and takes his place is community. I feel like, whether it's online or on land, community is something that everyone craves and you put it at the heart of this film. So channel Wendell for me on the importance of community.

Absolutely. The thing that steps up and takes his place is community. I feel like, whether it's online or on land, community is something that everyone craves and you put it at the heart of this film. So channel Wendell for me on the importance of community.

That's great. I think you totally picked up on the other reason why not having him visible is really significant.

He once said to me that our culture likes to idolize people, put people up on a pedestal. But it's not true. We are all just a function of those who are around us. I am defined by my family, my neighbors, my landscape. That is who I am.

There's a great quote in one of his awesome fiction books called The Memory of Old Jack. One of his most famous fictional characters is an old farmer named Burley Coulter and Burley says, “We are all of one another.” All of us. We are part of one another. I think that's essential to understanding Wendell's world view. If you look at the wood engraving image that comes up as the title card in the film, it's a picture of Wendell, but he's looking away from the camera. His coat and his body are made up of images from his place.

That's a huge part of it, too, and one of the other concepts that jumped out for me, as well … the idea of having intimacy with a place — really knowing the land and its inhabitants. That's such a huge part of Wendell's perspective and motivation.

Yeah.

Do you feel like that practice has been lost as folks have migrated into cities or can that still happen in urban settings? Can people have those sorts of relationships?

I hope so. It is a highly mobile society, though. I live in Austin. I moved here for grad school 15 years ago. It has changed dramatically. It was a sleepy college town when I came here and it has become a big, urban center. So I've seen that kind of displacement because there are so many people moving in here from elsewhere and that pushes the prices up and displaces all of the folks, like me, who can't afford to live here anymore. I think that mobility makes connecting to your place and putting down roots very difficult. It's financial or economic forces that are displacing us. So I think it's a real challenge.

However, I would say that I think the way Mary Berry talks in the film about taking a walk and showing your children how to look and see … and I think the example of Steve Smith, the farmer who reimagined his own farm and started a CSA — the first one of its kind in Kentucky — and paid off his farm … There are urban farms, there are all kinds of ways that one can connect to where he or she is. It doesn't have to be multiple generations on a single farm. [Laughs]

So I would answer your question both yes and no. I do think people can always find ways to root themselves and connect to their neighbors and their landscape and their kids. I think that's one of the beauties of Wendell's world view is that it shows you the large-scale problems, but the answer that he gives is always, “If there aren't large-scale solutions to large-scale problems, it's all about the small scale.” That's where you can have agency in your life and in your world. That, I find very empowering, for me personally.

Piggy-backing on that, there's the bit about mistaking small places for nowhere …

Exactly.

That is something I think we are all guilty of, if not individually, then collectively. But the lives lived in small places aren't a joke to be laughed at. I don't know if you'll agree, but it seems like this election season is highlighting that those people need to be taken very seriously.

Yeah. Isn't that fascinating? I agree. I'm from the South and I went to college in Connecticut. And I have this one foot in the documentary film world, but I also have the other foot as a stay-at-home mom with six boys in Texas. So I think that I'm well-aware of how these ideas are so polarized … the stereotypes of the South, the stereotypes of rural people. And the tyrannical political correctness of the documentary film world is very much of that ilk.

The Democrats think they are so enlightened, but there's a huge disconnect between urban and rural. That's, I think, one of Wendell's key messages. You can buy all the organic food you want at Whole Foods, but if you have a total disregard for the culture where that food is made, there's a degradation of the people, there's a degradation of the land, and ultimately, your consumption is not going to have any effect, if the economics are such that people think they can't farm.

There's a huge disconnect. Mary Berry said it wonderfully. She was at SXSW when we screened the film and she had a great quote about all the eco-consumers in Austin. She said as the demand for local and organic foods is going up, the number of farmers in the country is going down. She said that less than three-quarters of a percent of our population are farming. That is staggering.

So, yeah, there's a cultural divide there. And I agree: The election season is illustrating it, powerfully.

In the film, Wendell draws that line. It's populism versus capitalism which he frames as value over profit. When he draws the line all the way back to the source with “farming as art as life” … you can't separate those things. It's all Creation, no matter what your spiritual inclination might be. It's the political as the personal as the political. It all ties together.

Yeah. Truly! I love how you talk about it. That's encouraging to hear. I mean, I'm a Christian and Wendell's a Christian, but that doesn't necessarily mean that you're a right-wing propagandist. [Laughs] My politics are complicated and personal. I'm registered Independent because I can't attach myself to a formulaic world view. I was raised in a Christian family and I was taught those values, but there are many people who would hear me even say that and make a whole lot of assumptions about what a bad person I am. I'm so tired of those stereotypes. They are wrong and they have consequences. So, yeah, Wendell is definitely elevating the rural people.

I mean, I'm making a documentary and I know a bit about the documentary film world, which tends to lean left in a big way. I've always voted Democrat. It's not like I'm a card-carrying Republican, by any means. But I want there to be more complexity in politics. I say all that to say that the documentary film world, the powers-that-be in it are very attached to political correctness. I mean crazy attached. I thought, “What are they going to do with a film that looks lovingly at white, male, tobacco farmers from the South?” [Laughs] “What are they going to do?” It's been interesting. It's been embraced by some and shunned by others. I know that it provokes those politically correct radars in an anxious way.

[Laughs] The other idea that really struck me was the idea that making art equals making life, that you can look through a man's art and see him (or her). That must've resonated with you, as well, as a filmmaker.

Totally. Those of us — and I get the sense you're this way — who are trying to resist an industrial machine that tends to destroy everything we love, you try to find ways in your own life to do good work, to be inspired … to try to live a happy, good life against a lot of odds, these days. I think, for me, art is — and the Berrys reflect this — art is this beautiful way to work against the ugly things in the world. It isn't simply about a painting on the wall or a film.

Tanya Berry really elevates the domestic realm and imbues it with an artfulness. Like I said, I'm a full-time stay-at-home mom with six kids and part-time homeschool, yet I'm trying to be a filmmaker, too. There's often a sense of divide for me, personally. Tanya illustrates this. She elevates the domestic and shows that all aspects of life can be imbued with an artfulness because artfulness is, really, a way of seeing, a way of living. That, personally, helped me connect the different pieces of my life.

I don't have kids, but the whole thing about … when Mary's describing how they would make them look at things, make them appreciate things, and really engage them and their minds in thinking critically and with wonder. Gosh, if more parents engaged on that level, the world might have a chance.

I know what you mean. It's so crazy how our culture obscures all the most-basic things. You know? All this talk about education, but what about simply spending time with your kids and talking to them about what they see?

Or what they think or what they feel?

Right? Yeah. It's amazing how we obscure the most fundamental, natural paths, sometimes.

What was your biggest take-away from the project? What changed you? What has stuck with you?

Honestly, it was time with Tanya … kind of on a continuation of what we were just talking about. That's why the film goes there. It starts with Wendell and examines his fundamental, key arguments because I couldn't make a film about Wendell, in good conscience, without making classical arguments because that's what he would want. [Laughs] He wouldn't want it just to be an artsy-fartsy, feel-good piece. It has to have classical applications. So I knew I had to examine his ideas in that way.

But I think where we end up is with Tanya, mostly. I think there's a sense of hopefulness there. I think her connecting those dots for me, personally, between art and life was key.

And I think making environmental documentaries across the past 20 years can be very depressing. If you do the math, it's not looking so good, in terms of our natural resources — our fresh air, our clean water, our landscape … it's very depressing. At some point, I talked to Wendell about that and he said, “Of course you have to hope. Hope's a virtue. So we've got to find a way to have it.” I appreciate that because it challenges you. Like, “Quit sitting around whining. Find a way to create hopefulness in your own life. Make it happen.”

So, for me, personally, Tanya and Steve Smith, with his farm and CSA and the way he reimagined his landscape by looking for little glimmers of hope in his landscape, makes me want to find them in my own landscape and nurture them, grow them, rather than getting so overwhelmed with the looming specifics.

I'll be honest, I'm still going to do everything I can, because I believe in karma and I don't want this on me, but I think we're past the point of no return with the environment. It breaks my heart.

Yeah. Yeah.

If everyone had started doing everything they could 40 years ago, we wouldn't be here. But it hasn't happened.

It's amazing what we can do, when we want to. I think about us going to the moon and stuff. It's unbelievable what we can accomplish when we want to. I also think the resilience of nature is pretty freaking amazing. If we'd get out of the way, it can also heal itself pretty well. So I think there's good reason to despair, for sure.

But I know Wendell, through his work, points to the ugly in a very sobering way. It's hard. But, through the way he writes about things and talks about things, he shows the beauty there, and it's helpful, it's inspiring. So, hang on to that.

Photos courtesy of Laura Dunn and Wendell Berry

Absolutely. The thing that steps up and takes his place is community. I feel like, whether it's online or on land, community is something that everyone craves and you put it at the heart of this film. So channel Wendell for me on the importance of community.

Absolutely. The thing that steps up and takes his place is community. I feel like, whether it's online or on land, community is something that everyone craves and you put it at the heart of this film. So channel Wendell for me on the importance of community.