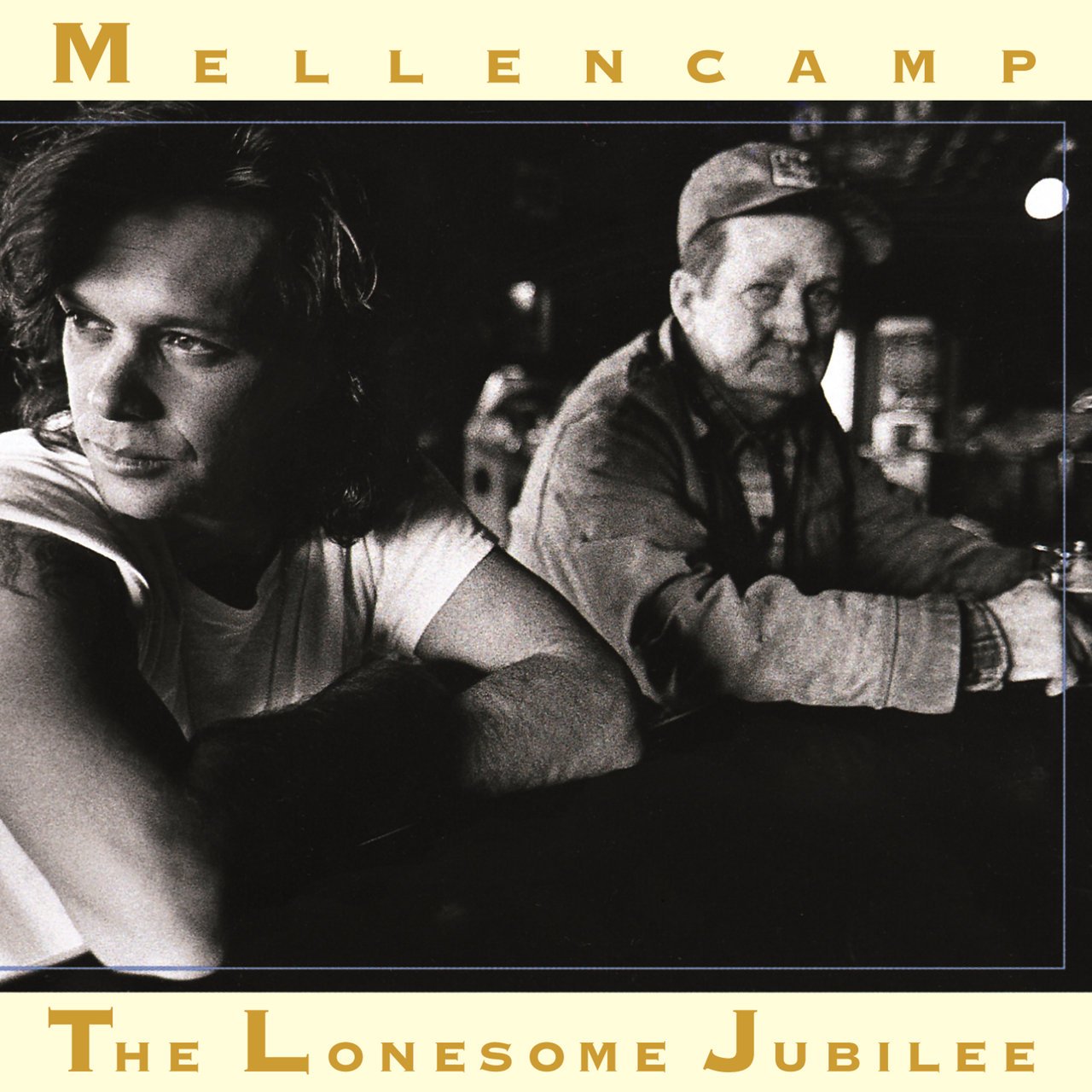

The Lonesome Jubilee was released on August 24, 1987, just a few weeks after Def Leppard’s Hysteria and a few weeks before Belinda Carlisle’s Heaven on Earth. But unlike those two albums, it is not getting a new 30th-anniversary edition. No remastering, no bonus tracks, no unearthed live cuts or alternate takes, no new liner notes, no think-pieces or take-downs. But John Mellencamp’s ninth album certainly deserves the deluxe treatment — and not only because it’s a rousing collection of politically barbed folk-rock songs. The best reissues allow us to hear old music in new ways, providing a fresh context in which artists might speak to a different moment and to a different generation. The songs on Jubilee speak very loudly, and they have as much to say in 2017 as they did in 1987.

Mellencamp recorded the album in late 1986 and early 1987, taking his road-tested touring band into his Belmont Mall Studio outside of Bloomington, Indiana. As usual, he worked with his long-time producer Don Gehman, who had helmed his breakthroughs during the transition from Johnny Cougar to John Cougar Mellencamp. Two crucial things had changed in the singer/songwriter’s life, one professional and the other personal. First, his longtime label Riva Records had gone out of business, leaving him briefly homeless. He soon signed with Mercury, where he remained for the next decade. Second, his uncle, Joe Mellencamp, died from lung cancer, and his passing lends the record an intense mortal resignation. While many of these songs may sound like they’re about other people, in fact they are about John Mellencamp delving into his family’s personal demons. According to a 1987 New York Times feature, he wrote first single, “Paper in Fire,” about “my family’s ingrained anger.”

By all appearances, it didn’t look like he had very much to be angry about. Mellencamp was coming off an incredible run that had established him as one of the biggest stars of the decade, alongside such well-remembered celebrities as Madonna, Whitney Houston, and Michael Jackson. Starting with 1982’s American Fool, he had devised a form of heartland rock that was unpretentious yet inventive, universal enough to appeal to anyone who heard it, yet eccentric enough to show the man behind the music. He had an easy way of rolling social and political issues into his songs, avoiding the all-caps melodrama of Springsteen, as well as the studious obscurity of R.E.M.

Sound followed setting. Mellencamp hailed from Indiana, where small towns were suffering, farmers were hurting, and regular Americans were shouldering the burden of corporate greed with nothing to show for it. In 1986, together with Willie Nelson, he co-headlined the first Farm Aid concert and testified before Congress in support of Iowa Democrat Tom Harkin’s Family Farm bill. In that same New York Times article, he explained that the giant corporations are “willing to exploit John Doe and let America become a third-world country, economically, if it benefits them.”

Throughout the 1980s, his populist mission informed songs that were based in strictly rock and pop sounds, in particular electric guitars. His catalog is littered with sharp and evocative riffs: the ominous growl of “Scarecrow,” the scene-setting rhythm of “Jack & Diane,” the horizon-expanding fanfare of “Rumble Seat.” While present on The Lonesome Jubilee, the electric guitar is primarily an accent to an arsenal of folk instruments largely foreign to MTV and the Billboard pop charts: fiddle and hammer dulcimer, autoharp and mandolin, penny whistle and accordion, dobro and lap steel. It wasn’t country, but it wasn’t folk either. Mellencamp called it a form of “gypsy rock,” rooted in his Dutch and German ancestry.

That musical palette gives The Lonesome Jubilee a special place in Mellencamp’s catalog and perhaps an even more impressive spot in pop music, more generally. Thirty years later, it might be one of the best-selling roots rock albums of all time, a bigger risk than the O Brother Where Art Thou? soundtrack; there is something brazen about Mellencamp’s embrace of these sounds, something ornery in his insistence that these traditions had a place in mainstream pop music. And yet, it still sounds like nothing else. His band deploys these instruments in unexpected ways, giving what might otherwise be guitar riffs to John Cascella’s accordion or Mike Wanchic’s dulcimer or, most often, to Lisa Germano’s fiddle. In particular, the strident urgency of “Paper in Fire” is grounded in her sharp bowing, which is industrial in concept if not in sonics: like squealing brakes on a car, or grinding gears in a factory, or perhaps a quarry saw through a block of limestone.

Mellencamp’s gypsy rock does a lot to tease out the meaning in his lyrics, whether evoking a specific regional setting in which these stories play out or simply providing an optimistic counterpart to his sometimes pessimistic worldview. If Springsteen (to whom Mellencamp is too often and unjustly compared) wrote about dreamers either escaping or succumbing to the drag of life, Mellencamp is much less romantic about the ordinary Americans who populate his songs. Rarely do they even have dreams or vistas that extend beyond the city limits. As Robert Christgau wrote in his A- review, “His protagonists don’t expect all that much and get less, but they’re not beautiful losers — they’re too ordinary, too miserable.”

When his characters reflect on their lives, they do so with a generational nostalgia that often obscures the source of their despair. “Cherry Bomb” is a gentle song about looking back to a more promising time in life. “We were young and we were improvin’,” he sings, but the implication hangs heavy in the melody: Age has brought personal stagnation. They’re just getting by, focused more on the golden past than the uncertain future. It’s easy to mistake the song for exactly what it lambasts — a rosy view of the past as paradise, when America was “great” and life was full of possibility. It’s a deceptive illusion: “That’s all that we’ve learned about happiness,” he realizes. “That’s all that we’ve learned about living.”

A politically left-of-center missive from the heart of the Reagan era, The Lonesome Jubilee requires almost no adjustment for the late 2010s. Mellencamp begins every verse in “Down and Out in Paradise” with the same refrain — “Dear Mr. President …” — before relating some poor soul’s story. It’s a ploy that recalls Woody Guthrie without being precious about the reference or, worse, deferential. Mellencamp knew Reagan wasn’t listening, just as he knows that our current president doesn’t have the capability to empathize with or understand the hard lives of the everyday Americans who inexplicably voted for him. Meanwhile, those same small towns wither, those farmers have long ago sold their fields, and regular Americans shoulder an even greater burden with less to show for it.

Perhaps even more impressive than sneaking dulcimers and autoharps into the mainstream is smuggling this brand of American fatalism into arenas and concert halls around the world. The ordinary Americans suffer while the rich stuff their wallets. Maybe you could have once argued that some things never change, but the discrepancy between 1987 and 2017 suggests that some things actually get worse. “Generations come and go, but it makes no difference,” goes the Bible verse that Mellencamp quotes in the liner notes. “Everything is unutterably weary and tiresome. No matter how much we see, we are never satisfied … So I saw that there is nothing better for men than that they should be happy in their work, for that is what they are here for, and no one can bring them back to life to enjoy what will be in the future, so let them enjoy it now.”

Maybe it’s not the most generous vision of human existence, but it’s certainly one that motivates Mellencamp’s empathy. Life is short, and we should make it as enriching as possible for as many people as possible. We should live squarely in the moment because yesterday, today, and tomorrow will all play out more or less the same. It’s a potent brand of cynicism, yet beautiful and American, too.