There’s a particular knowledge that is born only from a road-worn trek, like literature’s hero’s journey, where a protagonist adventures in pursuit of higher knowledge or power, someone like Captain Ahab or Tom Joad.

Kaoru Ishibashi, the musician known as Kishi Bashi, packed a camper during the pandemic and left his home of Athens, Georgia, wandering northbound through the American frontier that’s woven throughout the Western narrative. With newfound time and his daughter in tow, this journey was a personal exploration of Ishibashi’s own identity through the sprawling American terrain.

His trip took him to places like Heart Mountain in Wyoming, a World War II Japanese internment camp — a location he has visited many times during research for his upcoming documentary, Omoiyari: A Songfilm by Kishi Bashi, where he visits similar sites throughout the United States searching for the history that still persists today. The journey also carried him through the Ozarks and the Dakotas, and to small Montana towns like Emigrant — population 271 — just north of Yellowstone, and ultimately across the great expanse of the States to Oregon.

BGS chatted with Kishi Bashi about how this trip is intrinsically tied to his new EP, Emigrant.

BGS: What was the concept behind creating Emigrant? What drew you to creating the theme around the EP?

Kishi Bashi: I’ve been spending a lot of time in Montana the last several years — especially this year, since I had so much time. I took the camper out, took my daughter out, and we did this huge trip cross-country all the way to Oregon; we spread it out over a period of months. I got to enjoy nature in a way that I hadn’t in the past, to kind of imagine what it was like back then. A lot of rural places are pretty much intact; it pretty much is what it was like 100, 200 years ago. In Montana, it’s really cold, so there’s a reason not many people live there — but that’s changing. Emigrant is a town in Montana north of Yellowstone where a friend of mine had a cabin. I borrowed it from her family, and I stayed there for a few days and fleshed out a lot of the EP.

How is the title tied to the name of the town?

To be an emigrant is to leave somewhere in search of a better place to live. I found myself really searching my own identity, my own place in this country — as a minority or even as a musician in these COVID times — trying to find what makes me happy or what makes me a person. The symbolism was really great. [Emigrant] was a frontier town for a lot of people. It was literally the frontier of this violent place, both naturally from the weather, and it was a really cutthroat environment. I was also watching a lot of Deadwood before that — it’s up around there. It may not be historically accurate, but the vibe is definitely accurate. It was that frontier, settler, colonialism type thing. It was a really harsh place to live.

How did you plan your route? What were some of the lessons taken from the road trip?

With my daughter, we started in Athens, so we went up north, and there was a lot of driving. It was a good history lesson for her because we went to the Black Hills in eastern Wyoming — actually, that’s where Deadwood takes place — and how it was Sioux territory. We went to Mount Rushmore, and it was pretty unimpressive. There’s a Crazy Horse Memorial they’re building, which looks interesting and amazing. I was getting her to understand that this is a very complicated, nuanced, but violent history that existed in these lands.

I had the realization that if you live in a city — a town that’s been modernized over and over and over — you don’t feel what it was like back then. That paved road you stand on was a dirt road at one point. Before that, it was just a trail. You don’t really get to see that unless you go out to Montana or some rural area. We basically went straight up through Tennessee, Arkansas, South Dakota, and then cut over through Wyoming.

It sounds like this road trip was an American history lesson. Did you purposefully choose locations around Indigenous or Asian American histories?

Heart Mountain [in Wyoming] — where the internment camp was — I had been there many times. And my daughter as well; she has been there a couple times in the summer, because we’re filming there a lot for this documentary I’m doing. You can’t avoid Native American spaces in this place. It was interesting to see that a lot of the reservations were closed to outside travelers because their health infrastructure was so shoddy, and that people around them were bringing in COVID irresponsibly. That was heartbreaking to see; they were really desperate to keep it out.

Tell me about “Town of Pray.” Was it inspired by the actual town of Pray, Montana?

More by the name; the town of Pray is such a stoic name. I was reading this book — do you know who Jeremiah Johnson is? He’s this folk hero [also called John “Liver-Eating” Johnson], I think a real person, pioneer, Montana mountain man. I don’t know if you know the legend, but it’s such a violent place to exist. He had a Flathead [now known as the Confederated Salish and Kootenai tribes] wife, and she was murdered by the Crows. Then he went on a murderous rampage against the Crows, and then they respected him, and he joined forces against a different tribe. We have a very narrow narrative of what history is. When you see this violent history, it just makes me grateful that I don’t have to, like, kill other people to thrive, which may have been the case if you lived around there back then. You’re always watching your back. You’re always susceptible to trauma.

What are some lessons you hope listeners take away from this EP? Or lessons you learned through making it?

If people have the opportunity to go out and visit nature, get outside of your comfort zone and explore this country. And even more social justice issues, if you wander into any of these small towns, like in Montana — Bozeman used to be like 20 percent Chinese. Now it’s like zero. There’s a reason a lot of towns are white. After they built the railroad, they drove everyone out of town. Wonder why this country is not being shared by everyone?

You included two covers on your EP, [Dolly Parton’s “Early Morning Breeze” and Regina Spektor’s “Laughing With”]. Why were those chosen, and how do they tie into the overall theme?

One of the reasons was I definitely wanted to showcase female songwriters, because I looked at the Rolling Stone top 100 songwriters, and there were like two women in there — like Madonna and Dolly Parton. And it’s embarrassing. So I made an effort to do that. Of course, I love Dolly Parton just like everybody else. I always liked that song, and I thought it fit the vibe. The Regina Spektor song — I used to play for her; I was in her band — I always thought she was underrated, especially amongst musicians and as a songwriter. Lyrically, she’s brilliant, and she’s a huge inspiration for me. For the next generation of people who may not know her music, I wanted to point out that I have the deepest respect for her songwriting by covering her song.

Why lean into the folk or bluegrass genre for this EP?

It’s something I always wanted to do. This is also a disclaimer: I’m not a bluegrass musician. I don’t have much of a bluegrass situation amongst me, but I’m bluegrass adjacent. I went to Berklee College of Music and I studied with Matt Glaser, who’s an Americana teacher. But I played jazz violin. Gypsy swing, that’s my thing. I always loved bluegrass music, but I never felt, culturally, it was something I could attach myself to. I had this whole stigma, like imposter syndrome, of not being from a rural place. I’m a city dweller. It took me a while to own up to a fiddle tune.

As I became more comfortable with my own identity of being an American musician — an Asian American musician — I was like, “What if I just want to play something folky?” It was something I always wanted to do. So there are a lot of fiddle elements, especially in “Town of Pray.” If you think about “What is American music?” There’s jazz, there’s blues. Fiddle tunes come from a lot of Irish and Scottish roots in the mountains. American music is this huge conflagration of all these different cultures melding into each other. I think that’s the beauty.

And where’s my place in that? I’m an Asian guy playing a European instrument — violin — playing jazz, which is from the South with African American contributions. I always felt like I didn’t have a real identity as an American, so that’s probably why I felt so comfortable singing bluesy stuff, or putting a fiddle tune in there — just because I want to.

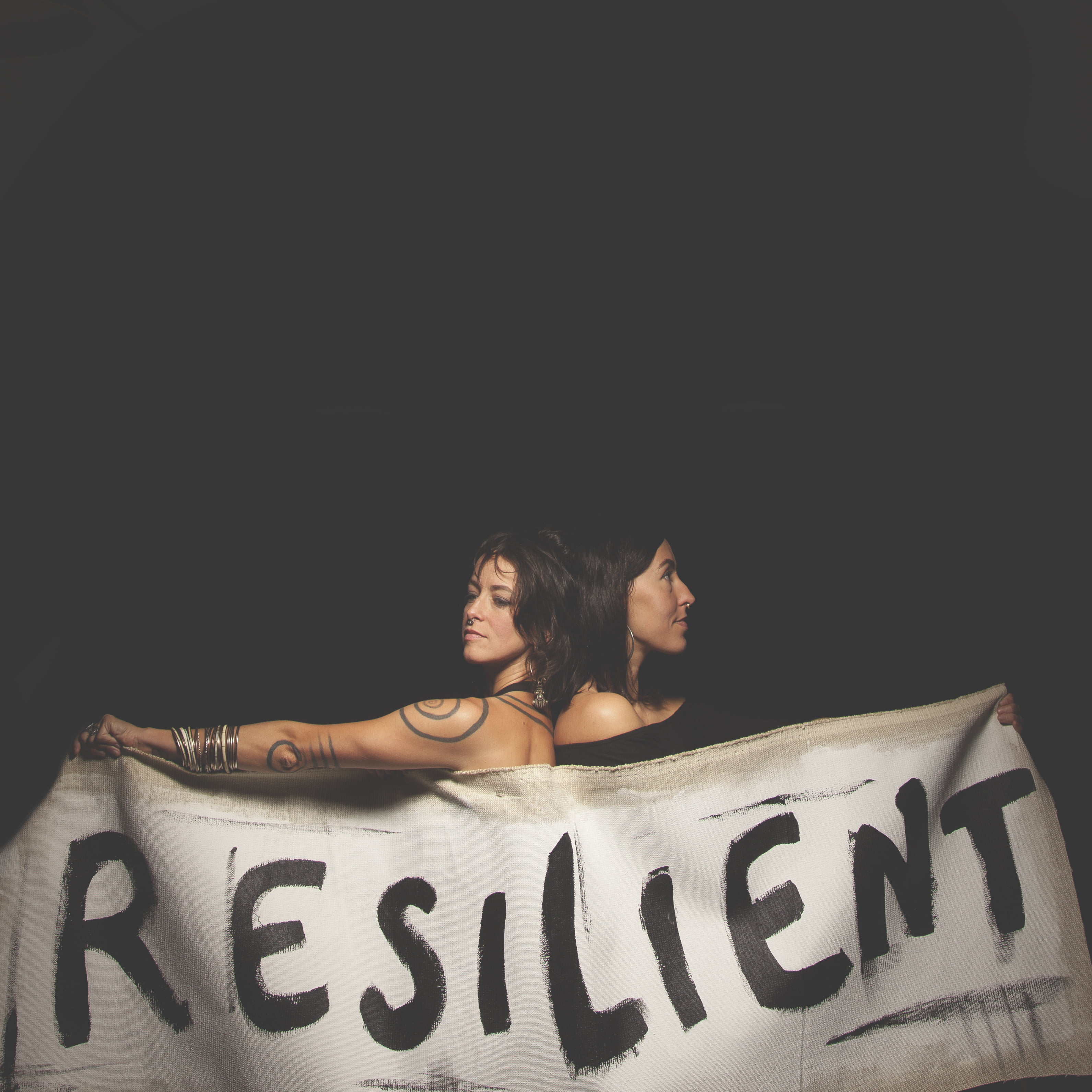

Photo credit: Max Ritter