It’s a mellow Fall afternoon in Carrboro, NC, shortly before the early-evening hustle to get home. A lot of students make up the little town’s population thanks to the adjacent town of Chapel Hill and the University of North Carolina, but Carrboro is also a home to artists and other creatives — its cheap living, easy-going attitude, and compact layout make it an attractive spot to set up camp.

The roots music upstarts in Mipso call Chapel Hill home, though they hang out more in Carrboro. Singer/mandolin player Jacob Sharp sits in a small brewery downtown, as the band’s new record, Old Time Reverie, pours out of the speakers. Sharp is quick to admit it’s weird, but that’s one of the perils of the area’s tight-knit music community — it’s as common to hear locals’ tunes playing on shop stereos as anything else.

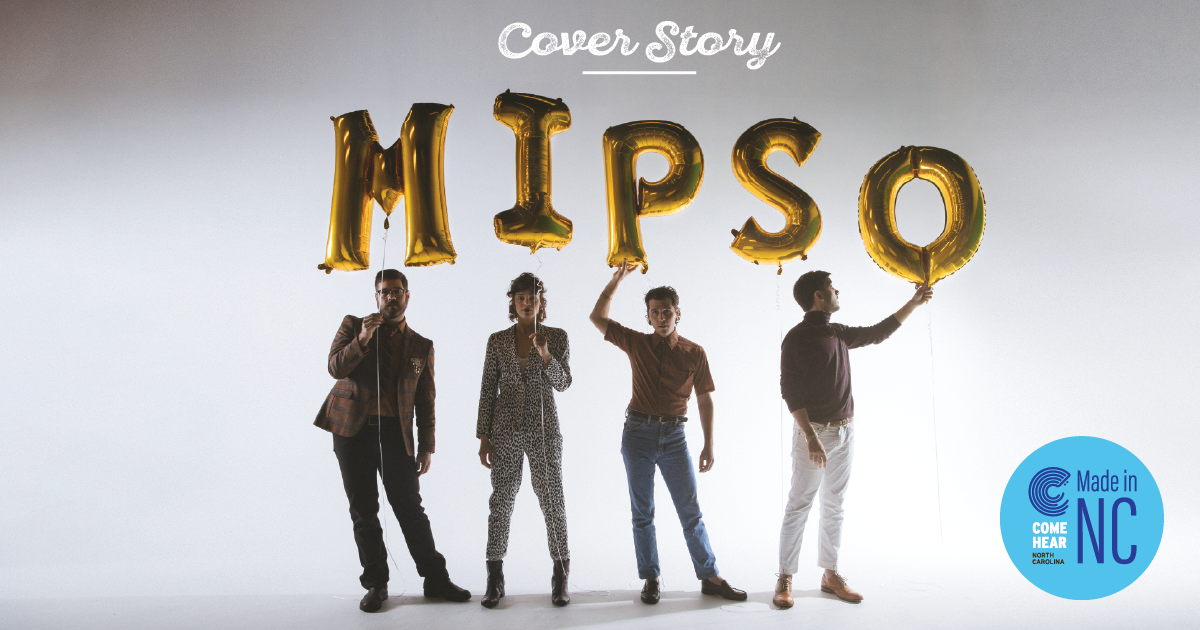

But this is hardly the most exciting thing going on for Sharp and his cohorts at the time: The day before, the newly released Billboard charts featured Old Time Reverie at the top of its bluegrass listing, at number 20 on its folk chart, and number 23 on its Heatseekers chart. The band spent the previous 24 hours fielding dozens of phone calls about the feat, but they didn’t see it as a big deal. For Mipso, the chart numbers were merely a passing recognition of something the band has already put years of hard work into, and its members hope that Old Time Reverie will help push them along even further toward a sustainable, long-term music career together. Guitarist Joseph Terrell, bassist Wood Robinson, and fiddler Libby Rodenbough join Sharp to discuss the band’s work up to this point and what they hope lies down the road.

Joseph, you mentioned in another interview that bluegrass was a big tent, and I think we’ve all talked about that together, at some point. Could you talk about that a little more and how y’all fit into that?

Joseph Terrell: I think there are a lot of great young artists that we’ve gotten to know, touring over the last couple of years. We have great respect for some of the early bluegrass guys like Bill Monroe and the Bluegrass Boys, Flatt & Scruggs, and the Stanley Brothers, but don’t feel like loving them and respecting them and playing music that feels informed by them necessarily means playing music that sounds exactly note-for-note like them.

Jacob Sharp: Within the context of the charts, it’s funny, because we’re also on the folk one, which is probably how I think more people would understand this album if they hadn’t seen the tags beforehand. I would think it’s a little more naturally under that point. I think it’s cool for Billboard to put it up on a couple, and I think it’s good for bluegrass that — as a genre and as a home — it’s become broad enough to sneak over there because, previously, that probably wasn’t as much the case. There were enough bands that pulled heavily enough from bluegrass to get cross-catch, but I don’t think any of us would really say this is a bluegrass album or that we’re a bluegrass band. But we’ll totally take being on the charts, and we love learning from that place and being a part of that community.

JT: I think it’s interesting from the charts' perspective, too, because the folk charts have Jason Isbell and Ryan Adams’ 1989 album. And that’s rock ‘n’ roll. They’re all a bit blurry, I think, right now. And I can imagine traditional bluegrass people saying, “Wait a second: If you’re not going to use this as a bluegrass chart, then why have it? If you’re going to broaden it to be acoustic music, then call it acoustic music, not bluegrass.” So I can understand how the terms get frustrating when you try to really understand what they mean.

You’ve spent a lot of the last year on the road. How has that been? Do you feel like you've gotten into the swing of it now?

JT: It’s definitely been a big adjustment. We live in Chapel Hill, but to say we live anywhere is kind of a stretch. At some point in a touring musician’s life, when you’ve been a musician for a long time and traveling a lot — for example, like we were talking about earlier, when you wake up on a Tuesday in the middle of Iowa in February, you have that sense of, “How did I get here? Where am I going? What am I doing?”

JS: That question of “How did I get here, where am I going” is in both senses — like, “Where was I yesterday? How did I actually arrive in this location? And what happened over the last two-and-a-half years of my life that I thought this was rational? What major glitches in logic have I found?”

JT: There are great things, too. We’re all grateful for having gotten to know so much of the country. I think that sounds like you’re trying to find a way to make it sound good, but genuinely, it’s been super cool.

Before you hit the road, how much of the Old Time Reverie was done? How did you fit recording and writing into your touring schedule?

Wood Robinson: The songs were pretty much written before we got in the studio in December of last year. We had a week there, and another week in early January, and a final week in early February between the Northeast run and the Midwest run. It was basically all done before the breadth of the year happened.

JS: When we were touring in 2014 — Summer and Fall — that was really our transition into full-time touring. We had carved out time. We wanted to understand the motions of touring before getting into the studio.

Libby Rodenbough: There were very discrete sections. We had to very intentionally set aside time for recording, and it was very scheduled. I know some people who record as they’re on the road, and they do a few days here and leave for a few weeks, and do a few days here. For us it was like, “This is now studio time,” and then back to the road again after that.

Many contemporary folksy bands style themselves to be sort of old-timey looking, and y’all definitely don’t do that. Has that been a really conscious choice?

LR: It is not really that important, and I don’t think that we spend so much time thinking about it. But it is kind of tricky to negotiate that. I find myself wondering sometimes if I’m playing too much into a stereotype. I think, even though we dress in regular 21st-century clothing, it’s also kind of influenced by our general aesthetic tastes. It’s not a mistake that we’re all from this area, and we all listen to some acoustic music, and we like leather boots. We like rural-influenced-type clothing — it’s not like we’re dressing up like cowboys all the time, but we have those inclinations.

I think it has to do with family history, but also, in our lives, we’re drawn to many things like that. I studied a lot of folklore in school, and I’m drawn to the traditions of the South — musically and culturally, generally, and also aesthetically. So I think that’s part of the way we dress, for sure. But you don’t want to be too thematized in a band in a certain genre. And I think that has to do, too, with the fact that we don’t want to be pigeonholed as playing a particular type of music exclusively. And if we were to dress a certain way and have a banjo in our band — there are certain cues you can give your audience, and we don’t want to give them those cues.

JS: I think style, like everything else you do from day to day, the more you do it, the more you think about it in more nuanced and critical ways. Going into this album process, we were thinking about the imagery of the cover and the clothes we were wearing in a different way than we had previously. Libby thinks about that stuff a lot, individually, and we thought about that stuff, collectively. This time, we worked with Dear Hearts, from Durham.

LR: I think it is worth noting for someone like me — who spends way too much time and way too much money on clothing anyway — I would be doing this regardless of whether or not I was a performer. It’s just a passion of mine. But when you get to be onstage and wear some of this stuff, there is some semblance of justification for it, which makes me feel better about myself. I would say it’s one of the perks of being a performer that, if I buy, for example, gold sequin pants, I can be like, “Well, this is for the stage! This is just a business purchase.” I don’t write it off, but I do buy some things like that with a very slight sense of justification, and I appreciate that.

JT: An example for me is, I recently saw a band performing with a microphone that was as big as a dinner plate. I said to the other guys that I thought that it was a real failure of the microphone that it amplified the voice well, but it distracted from the performance completely. If I wore gold sequin pants, and someone left the concert and all they thought about was my gold sequin pants, I think that would be a failure of my style. I want people to leave our concerts thinking about music and thinking about our songs. That being said, it starts to make sense to be thinking about how your clothes play a role in what people think about you. I don’t think it’s wrong to wear something you think is cool, but we’re not David Bowie exactly.

LR: We are the David Bowie of bluegrass.

What do you see for yourselves in the next year-plus?

LR: I think a lot of what we see is the same … but more. The same … but better. Probably hitting a lot of the same areas and doing a similar level of touring, in terms of how many days on the road, but hopefully better gigs and better attendance and cooler venues. The things that we see happening already — the people that we’re meeting, the bands we’re getting to play with and stuff — leads me to believe that that will happen. It feels like we’re headed in the right direction.

JS: It’s a funny thing to be learning about. You start to understand it in these cycles that are, like, 16 months in the future. This album was done in January, the songs are just now new to the stage but they’re old songs to us. We’re excited to get into the studio, but we understand that when that happens sometime later next year, there’s no way it can come out before February of 2017. You start to understand stuff in a weird world, these chapters that kind of have a slow roll.

LR: Somebody asked me recently, “Is it full-time?” I thought, it’s way more than full-time. It’s full life. It’s what I think about all the time. When we’re on the road, it’s pretty hard to fit anything else into your brain that isn’t band-related. I would love to have the time and, thus, the brain space to remember the other parts of who I am. I love being invested in the band, but I think it can get a little too much and, if we’re looking at longevity as a group, I think that actually depends on having some individual focuses that are far afield.

WR: There are only so many years you can tour 180 shows, which translates to, like, 220 days a year. You just can’t. You physically reach a wall, and we’re young enough to maybe prolong that wall a little bit further down the road. But it feels good to be consciously making changes in that regard.

Do you find it difficult having to balance thinking about all these long-term things with being present in everyday life?

WR: The one thing that catches up with me — it is my life, so it’s relevant and it isn’t just business. But, often times, when I call a friend, I don’t want to talk about music. And that’s impossible if that person is in music. It feels fake or something like that, sometimes, when you’re talking about your career, because it feels like you’re having a business talk about your hopes and dreams and stuff like that when you’re talking to a friend you’ve had for years. It subconsciously happens. You’re not actively trying to push your career on other people, but that is basically everything we do, so that is what’s been going on.

LR: And you get used to conversations that are kind of about you, and they’re uncomfortable, a lot of the times. There are a lot of conversations after shows, where you’re trying to learn how to gracefully reply to a lot of compliments that start to feel kind of meaningless. I find that when I return to talking to a friend who doesn’t give a shit that I play shows, it’s refreshing but also kind of disconcerting. I sort of snap out of a fog I’ve been in on tour. And, when you have those moments, you realize a certain kind of unreality or different reality that you’re in when you’re on tour. But sometimes it’s not other people imposing it on you. You can’t get yourself to stop talking about work. I’m in my own head, fighting with myself, like, “Stop talking about the band,” but I can’t think of anything else, because it’s all I do and think about most of the time.

Photos by Katie Chow for BGS