Like her appellation, Bedouine (Azniv Korkejian) has wandered far from where she first began. The nomadic impulses beating at the heart of her chosen stage name carried her from her birthplace in Syria to her self-described home in Saudi Arabia as a child and later to the United States, where she continued shuffling from Boston to Houston to Lexington to Savannah, and eventually Los Angeles. But with that kind of existence forming the bedrock of her identity, and the mystery — not to mention magic — of new places constantly calling, what does it take to stay? Nothing really so romantic, really. Just a choice. Thanks to the artistic community she eventually found in her most recent adopted city, Korkejian has sacrificed the wild call of the road to instead see whether or not the old adage about blooming where you’re planted holds salt … for now.

Rather than focus entirely on her wandering ways, her self-titled debut traces the surprising blossom of love for one so used to traveling light. On “Heart Take Flight,” she spends the first meters of each verse allowing her voice to convey its full dusky depth before loosening it to rise to a joyous conclusion. The chorus’s simple maxim, “Heart take flight. I give you every right, when he’s around,” not only encourages mindfulness, but also acts as a kind of permission: “Dive in, it’s okay.” But Korkejian’s lyricism contains an enchanting ephemerality, as if she knew one day she would need to sing these songs to herself. The “you” surfacing throughout the album shifts from lover to self as time carries the message back to the messenger. In “Dusty Eyes,” she ventures forth her feelings, but her declarations feel as much to herself as to anyone who has momentarily captured her heart. “The lampposts burn the night, but they don’t come close. No, they don’t come close to the way that I feel about you now.” If movement involves a process of self-discovery, then Korkejian traces a similar means of self-exploration by choosing where to stay, and for whom. The answer may have initially involved someone else, but by the album’s end, it largely comes down to her.

Written over the course of three years, Bedouine came about after Korkejian heard what Matthew E. White’s Space Bomb studio had done for artists like Natalie Prass. She sent him a demo, and something about the confluence of her lyricism, the space she breathes into every song, and her soporific yet self-assured voice wasn’t so easily brushed aside. It’s easy to hear why on songs like “Solitary Daughter” which reverberates with independence — the kind fought for after years of self-doubt and discovery. “I don’t want your pity, concern, or your scorn. I’m calm by my lonesome, I feel right at home,” she sings. Korkejian’s debut comes in her early 30s, a refreshing place for a new voice to enter the conversation, as she eschews the often-solipsistic questioning that takes place earlier in life, and instead enters quietly yet assertively to offer a different, more internally robust, picture of the wanderer enticed to stay.

How have you curated a sense of rootedness within all the movement you’ve experienced?

I don’t know that I have, to be honest. I love L.A. — I think it’s the closest thing to home that I’ve felt in a really long time. But I think when I left Saudi Arabia as a kid, I had this pent up resentment like, “As long as I’m not there, I may as well be anywhere.” I was pretty intentional with anything I acquired: I wanted to stay light on my feet; I wanted to know I could move myself place to place on the drop of a dime. It’s only recently that I was like, “Maybe I’ll buy some furniture.” I do want to feel at home in L.A., and it’s a current process for me.

Like choice over happenstance.

Yeah, I think so. It’s largely due to the people that I’ve met. They’re so wonderful and talented, and I feel so inspired, and it wasn’t until I moved to L.A. that I pushed myself to be a better writer. There’s no room for mediocracy there. Not to say that I’m so great — I just felt like I got better.

It’s the kind of record that demands attention. I think that’s part of its power: There’s a soothing quality about it.

Thank you. There are times I’m singing and I think I’m singing my heart out in there, and I go back to listen to it and I sound half asleep. It’s just what I know. I don’t know how to sing any other way. Growing up, I loved to sing a little bit more bombastically, but it was always to other people’s music. I don’t think it’s conducive to the kind of song I write, and I’ve learned to accept that — that it’s a different quality.

You’ve drawn comparisons to Judy Collins and Nick Drake, and especially Leonard Cohen in terms of your lyrics’ poetic quality …

Which is totally fine!

Not a bad comparison! So that blend of the poet’s voice — quiet but insistent — alongside the melodic, what are you turning to for guidance? Other writers? Something else?

[Regarding “Solitary Daughter”] The whole thing was so reactionary. It just poured out of me that one night; I didn’t even stop to ask myself what I was trying to say exactly. The language is so figurative, and I leaned into it without interrupting it much. It felt so internal. I don’t think I was reading anything at the time that found its way in, necessarily. It was just a really emotional experience writing it.

I know people have fixated on the claim of solitude you make, but you’ve also said it’s about experiencing a relationship as two whole individuals rather than hoping such a connection will make you whole.

Yeah, I’ve had to backpedal a bit to understand what I was saying. It’s inspired by that quote, “No man is an island.” It’s about empathy and isolation, and here I am singing this song that says like, “Leave me alone, leave me alone.” I had to dig a little deeper, like “Why did I say that?” I had to come to terms that it was about this specific kind of relationship: If I’m doing something entirely on someone else’s terms and I’m not being considered, that’s why I’m saying, “Leave me alone.” But then I sing about an ocean, and an ocean is about connectivity, but it’s also about a self-sustaining, rich internal life existing underneath a surface. It’s fine on its own. It doesn’t need tending to, but it also connects everything together. It’s been a joyful process, breaking that down.

Discovering and rediscovering, in a way.

Yeah, it’s revealed itself to me, in a way.

This is just one interpretation, but I think of it as a love song both in terms of what one offers to oneself.

I love that. Someone brought up with me that it’s not as common to hear a woman singing about a rich internal life. I didn’t even think of it that way, but it must’ve found its way in there. As a woman, maybe, I feel a little bit protective of myself in a way that I don’t want to be perceived as “less than.” I also don’t want to overcompensate, but sometimes you feel you have to. I think it does say that: “I’m happy with myself, and if you can’t see me as an equal, then there’s no reason to continue.”

Yes. Also, too, I think society doesn’t know what to do with women who are out in public and visibly, comfortably alone. So I love that you’ve managed to cultivate this rejoinder to that.

Yeah, it is. And it’s a pretty passionate claim, too.

Another love song that struck me is “Heart Take Flight.”

I’m so happy you feel that way because no one has asked me about that song.

How much would you say that your movement has made you guarded to a point where you have to remind yourself to enjoy those romantic, vulnerable moments when you find them?

Absolutely. That song is like a memo to myself. I wrote it when I first fell in love with someone, and I thought to myself, “I can’t forget the way this feels.” You hear about love or feelings fading or building an immunity to it, and I wanted to remember the way I was feeling at that moment.

A reminder and also a permission, which I thought so haunting.

Yes! I haven’t had to talk about this song, so I’m still sorting this out, but, yeah, it is about giving my heart permission to let go a little bit. And it is a counterpart to “Solitary Daughter.” Like a bookend.

Also, what you were saying before about rootedness and the materialism it engenders — buying furniture — it also means attachments, and people can be part of that equation.

Yes, so to speak in terms of the song, “Back to You,” which is the third track, that is a song I wrote about having an instinct to leave Los Angeles, but staying for someone, so it all kind of connects, in a way. What I’m saying in that song is, “It always comes back to you. That’s why I’m here.” It doesn’t make a huge case or anything, really. It’s just more of an observational song. Taking in L.A. and trying to understand everyone’s place there and what they do, and being confused about it sometime. Taking note that I’m there for that reason, and trying to be okay with that.

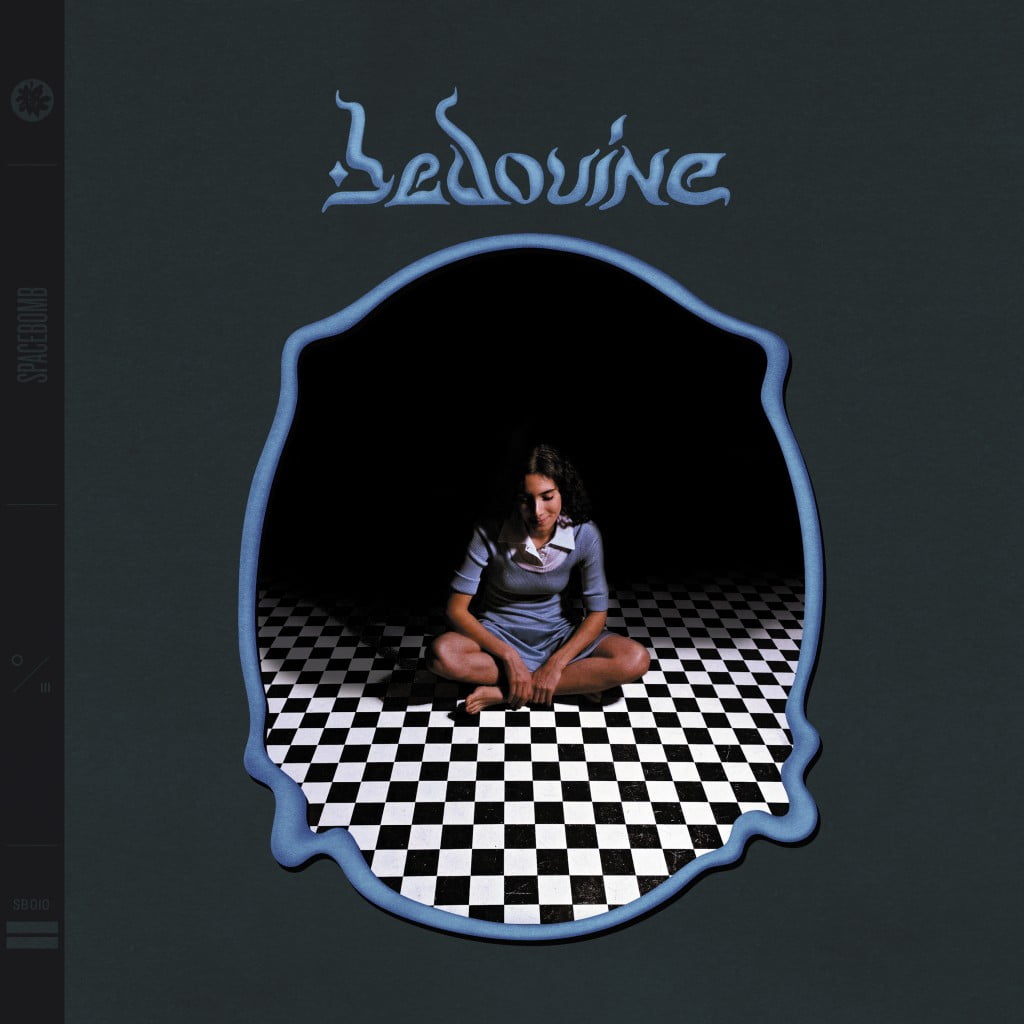

Definitely, and what we were discussing before about choosing a place. There’s freedom in that action, but it can be overwhelming in how you define and create “home.” Turning to the cover, I couldn’t help thinking of Alice in Wonderland. What was the intention behind that?

That was not intentional. Yeah, a lot of people have said that ,and I totally see it, and it actually kinda works with this whole theme. That photo was taken from a series of photos that my friend Polly did. The floor — that was the studio we recorded the record in. Before, you could see the background, but the photo was more striking when we blacked out the background and brought the shadows down. We didn’t shoot it with the intention of it being the cover, but I started messing around with a lot of templates, and I was looking at Nick Drake’s cover of Bryter Layter, which I think is one of the most beautiful album covers, especially the color combinations, and that lavender with the bright orange, I thought was so cool. I didn’t want to take that, as much as I did the oval pendant.

As a frame.

Yes, I love that frame. I think it’s so sweet and elegant. I brought that idea to Robert Beatty. He lives in Lexington, Kentucky, and I’ve always been a fan of his work, but in the last two years he’s gotten some really big records, but thankfully he did it. He made it a little psychedelic. The thing about it, which also was not intentional, it looks like a book cover, especially with the Space Bomb banner. To help with the symmetry of the record, we extended the banner, so you’ll see it looks different than their other releases.

And here you also created such lovely space throughout the album.

We were 30 songs deep, actually. We were just recording bits and pieces and slices of time — this is over the course of the last three-and-a-half years. They inherently had so much space to them because nothing was over-produced. When Matthew became interested in the record, we cherry picked our 10 favorite songs, and because we were aware of their process and how they wanted to put arrangements down, it worked out where it was like, “Let’s not over-produce these songs. If anything, let’s give them more space to work with.” They had to finagle their arrangements, which is something they normally have in mind when they’re producing.

That would have been a curious way to go about shaping this as a record.

I was so nervous about it because I had so much time to grow attached to these songs exactly the way they were, and I also fell in love with the space. “Heart Take Flight” is the perfect example. I presented it to Matthew as an afterthought and he was pretty passionate about “Heart Take Flight” being on the record. At that point, Trey had already started writing the arrangements. We didn’t intend it to sound so Nick Drake-y, and so Gus had to counteract that with something different, which is why he chose to put the moog on it, so it became a little less traditional. I didn’t listen to a Nick Drake song and think, “I’m going to write this.” I just changed the tuning on my guitar and started writing that. At the time, I really liked the method of seeing how long I could stay on one chord for, which is what I did for “Solitary Daughter.” I didn’t see it as an issue, but Gus said we needed to back away from that.

It’s a haunting sound, akin to a finger running over the rim of a wineglass.

Yeah, it’s so round. I think it worked out because it leant itself to an otherworldly type of thing. That’s a reference I gave to Robert Beatty. This is a perfect example of what the artwork could do: Traditional and simple, but notes of otherworldliness.

All of which came across. It’s really striking altogether.

Thank you. I’m so in love with the artwork.

I’m excited because when you’re talking about having 30 songs and carving them down to 10, that means we get more albums in the future, right?

Oh man, if I wanted to, I already have the next two records written, but I do want to challenge myself to keep writing. I have such a backlog of stuff that I didn’t record.