Sometimes you have to be willing to make sacrifices for your art. Sometimes you spend extra hours rehearsing or extra days touring; sometimes you have to become a martyr for a larger cause. Sometimes all you have to do is wax your chest.

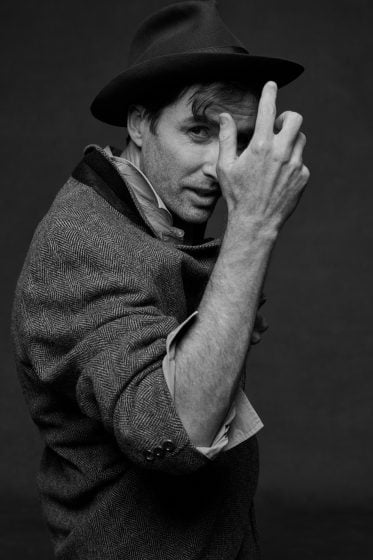

On the cover for his latest album, the cheekily titled My Finest Work Yet, the Chicago-raised, LA-based multi-instrumentalist and virtuoso whistler Andrew Bird lies in an old tub, his head hanging askew: the poet on his deathbed, expiring after scribbling his final testament. He recalls, “A few days before the shoot, the photographer said, ‘OK, you have to wax your chest!’ She wanted me to be as smooth as a dolphin. My first thought was, ‘Oh lord, is she just testing me? Is she just seeing how committed I am to the concept?’”

Bird’s chest hair. “We just ran out of time,” he says, no small amount of relief in his voice. Despite his hirsute torso, that image is startling, beautiful yet gruesome, and strangely fitting for an album that examines in a roundabout way the artist’s responsibility to his audience.

The cover is based on Jacques-Louis David’s 1793 painting The Death of Marat, on view at the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium. “I stumbled across that image in a book called Necklines, which is a funny title for a book about the French Revolution. I had already decided to go with My Finest Work Yet for the title, and I was trying to find an image that would make that title work, that would make it funny. When you don’t know the history of that painting, you just see the suffering poet on his deathbed penning his last words with his dying breath. I thought it was pretty tongue in cheek,” he says.

The more research he did on David’s painting and its subject, the more it revealed a slightly more serious, slightly less self-deprecating undercurrent running throughout these new songs. Jean-Paul Marat was a radical journalist during the French Revolution and one of the leaders of the insurgency against the Crown. He took frequent medicinal baths to soothe painful skin infections, and he wrote most of his most famous works while soaking in his tub. That’s where he was assassinated by the conservative royalist Charlotte Corday; shortly after, David painted him as a martyr, a stab wound to the chest stained his bathwater red. “We went to great lengths to re-create the painting,” says Bird. “There’s a lot of detail, but we drew the line at blood. It felt like if I had the wound and a bathtub full of blood it would go just a little too far.”

An album that might actually live up to that title, My Finest Work Yet, makes clear that we are living in revolutionary times, that we are at the precipice of some great calamity, some great upheaval. “The best have lost their conviction, while the worst keep sharpening their claws,” Bird sings on “Bloodless,” a sober, even scary examination of American factionalism. “It feels like 1936 in Catalonia.” That last line might sound cryptic, but it is a reference to another revolution – not the French uprising, but the Spanish Civil War. “There’s a lot to unpack in these songs,” Bird admits. “Maybe you don’t know what happened in Catalonia in 1936, but you’ve got Google and three minutes to figure it out. I think that makes people a little more invested, maybe not quite knowing what the references are but hopefully thinking, ‘I need to find out.’”

His lyrics have always been brainy, often bordering on merely clever, but the allusions to the French Revolution and the Spanish Civil War — not to mention to Greek mythology, J. Edgar Hoover, Japanese kaiju, and whoever Barbara, Gene, and Sue are — lend the album weight and timeliness, as though we might better understand our current political predicament simply by looking to the past. And the artist in 2019 might understand his duties by looking to past examples like Marat. “The flipside to music being devalued as a commodity these days is that it can maybe make even more of an impact than any other medium can. Everything is commodified, but music is slipping away, but it’s still this thing that is very powerful. It helps people get through hard experiences,” Bird says.

Released back in November following the midterm elections, “Bloodless” was the first song on which he found just the right vocabulary to sing about issues that he and so many other artists are pondering. It was also the moment when a sound gelled alongside his lyrical strategy — a sound that incorporates bits of folk, pop, gospel, even jazz. Bird was fascinated with what he calls the “jukebox singles of the early ‘60s,” when jazz vocals were popular, when the piano was a prominent pop instrument, when bands worked out songs and recorded them live together.

“The piano contains so many references, a couple centuries’ worth,” he says. “Our ear gets taken in certain directions, but something was happening during that period in terms of not overly complicated jazz and gospel. I knew I wanted to make a piano-driven record with Tyler Chester, and I knew I wanted to make a jazzier record with a good room sound. And ‘Bloodless’ was the first time we got it right.”

Bird and his small jazzy combo recorded live in the studio, which wasn’t easy. It involved rehearsing heavily and using only a handful of microphones. He says, “There is so much work before you record the first note, so it’s risky. But if you spend the time, you end up with something that I think is weightier and has more value, even if it goes against the last 34 years of production trends.”

There is a lot of bleed between the instruments, which creates an intimacy even when you’re listening over your computer speakers. However, it means you have almost no opportunity to make changes after you’ve recorded a song. “If you want to change the vocal sound, you have to change the drum sound. If you want to change the drum sound, you have to change the bass sound. Everything is connected,” he explains.

It became a house of cards. Remove one and the whole thing tumbles. That meant Bird had to surrender his usual self-criticism to focus on other things besides listening to his own voice. “When you record, you have to have something to fixate on and fetishize — something that has some ceremony to it. Maybe it’s a certain microphone that gives you a certain sound, or a tape machine. It helps you remember who you are,” he says. “I tend to forget who I am when I’m recording. I know exactly who I am when I step onstage, but you have to trick yourself into being yourself in the studio. I liken it to hearing your voice on an answering machine, and you’re like, ‘That doesn’t sound like me.’ Same thing happens when you’re recording: You hear yourself back and you don’t recognize yourself.”

During the sessions for My Finest Work Yet, Bird focused on the piano and more generally on the live-in-studio approach to keep himself centered. Rather than make him more prominent, however, it only makes him one musician among many: the singer and creative force, certainly, but only one member of a lively band. That connectivity — that sense of musicians joining together in a common artistic goal — is “philosophically important,” says Bird, as are the pop references he’s making with that approach. “The music I’m referencing was deep in the Civil Rights era, the beginning of all this activism and turmoil. I wasn’t thinking about that when we were in the studio, but I think it makes sense,” he says.

In other words, those connections weren’t planned, which means My Finest Work Yet lacks the self-seriousness of a concept album or the self-righteousness of a political album. Instead, Bird wrote and arranged and recorded intuitively, as though posing a question to himself that would be answered on this album. “I’ve always had a tendency to say, ‘Here’s some stuff I’ve been thinking about,’ but I’ve always trusted that the listener has the curiosity and intelligence to think about what I’m bringing up.”

Photo credit: Amanda Demme

Illustration: Zachary Johnson