Been around the world, seen some of everything, but what I like about it the most is the joy that I bring…

– Robert Finley, “Livin’ Out A Suitcase”

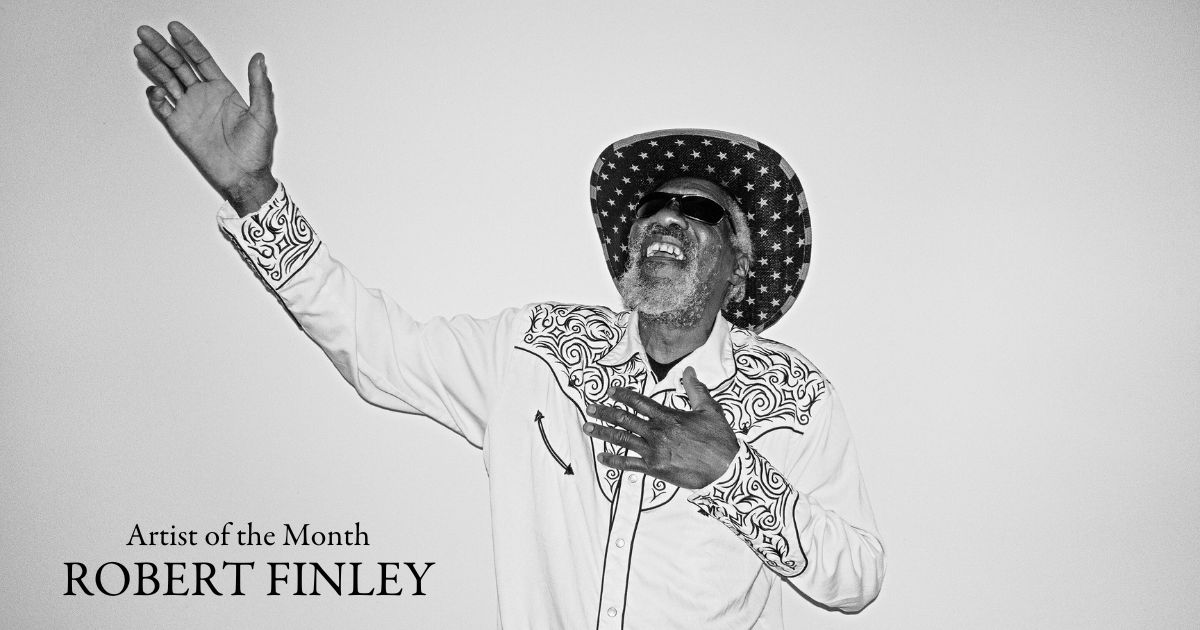

Whether it’s at home or abroad, Robert Finley’s youthful exuberance has a knack for not only lighting up rooms, but people’s faces as well. On his latest batch of songs, the former sharecropper and carpenter – who got his start in music during a stint in the Army – continues that trend with 11 stories pulled from his Louisiana upbringing that include everything from the poignant “No One Wants To Be Lonely” to the cheeky and overly embellished “Alligator Bait.”

Pulling from rock, soul, blues and a whole lot of gospel, Black Bayou is easily Finley’s most personal and sonically developed record to date. His third project with Dan Auerbach and Easy Eye Sound, the record is one that came about organically, feeding on the artist’s energetic live performances with lyrics and arrangements put together on the spot in the studio with no pre-fabricated blueprint.

“When we did this album there was no pencil or paper in the room,” Finley tells BGS of the process. “The band was free to jam what they felt and I had the freedom to say what I felt. Nothing was written beforehand, it all came to life in the moment.”

Born in Winnsboro and now based in Bernice, a North Louisiana hamlet only thirty miles from the Arkansas border, Finley has excelled at living in the moment despite the fast moving world around him. That essence is what accelerates his storytelling throughout Black Bayou, particularly on songs like the aforementioned “Livin’ Out A Suitcase” and “Nobody Wants To Be Lonely,” the latter of which has the artist crooning about the elderly sitting at nursing homes around the country with no family wanting or able to keep in touch or care for them. It’s a topic that Finley doesn’t just sing about from the studio, though. He visits nursing homes in his community on a regular basis to serenade its residents.

“So many people have been forgotten,” says Finley. “Their kids drop them off and go on with their lives. I go down occasionally and perform at the old folks home in Bernice. Just take my guitar and play for 30 minutes or so, try to get them to dance, try to bring some joy to them.”

Whether in those homes or the local clubs, Finley is determined to use his platform to give back to the community that made him. In addition to never turning down a conversation or photo op, he also aims to lift up the next generation of musicians, offering support and guidance to those cutting their teeth and in need of a role model as they pursue their own musical dreams.

“I always go back whenever I’m not on tour, simply because that’s where I got my start,” says Finley. “It also gives me a chance to encourage the young artists there to pursue their dreams, because I can share how I started busking over there on the corner eight years ago and now I’m touring the world. Had I not made that first step, then nobody would even know what I was capable of doing.”

As listeners have come to expect from Finley, Black Bayou is full of lust, love, spirituality, and humor as well. Tunes like “Sneakin’ Around,” “Miss Kitty,” and “Can’t Blame Me For Trying” showcase Finley’s flamboyant and flirtatious side, which goes hand in hand with his center-stage shimmying and shaking at live shows. On the flip side, cuts like the swampy album closer, “Alligator Bait,” unravels as a spoken word recollection of a formative day on the bayou with his grandfather with a gnarly and always evolving backbeat oozing with attitude.

Together these stories make a patchwork quilt of sounds, emotions, and stories that only Finley could piece together. Calling into his North Louisiana home, we spoke with Finley — our November Artist of the Month — in detail about Black Bayou, making music with his family, the similarities between performing and preaching, and more.

What has busking taught you about performing and holding an audience’s attention?

I’ve learned that you don’t need to put all of your eggs in one basket. I’m always trying to shake it up and introduce new things to the crowd at my shows, because no matter how good a movie is, if you watch it two or three times you’re going to know exactly what happens next. It doesn’t mean it’s not a great movie, it just means you’re not going to watch something that you already know the result of. I don’t want to rehearse and be programmed to do the same thing over and over, I need to have the freedom of the spirit of the moment.

Your daughter Christy Johnson and granddaughter LaQuindrelyn McMahon both joined you on this record. What’s it mean to you to share your love for music with them?

It’s great being able to have three generations of Finleys singing together. I’ve always admired Pop Staples and The Staple Singers for him and his daughters. I have two other daughters as well, but they both work in the medical field and can’t just uproot and follow me around the world. My oldest is a licensed beautician, but put it on hold to help me pursue my career due to my sight being bad. She saw that I was determined to do it either way, so she sacrificed hers to make sure I wasn’t alone. Because of that I want to share the spotlight with her every chance I get.

She first came on during the audition process for America’s Got Talent, which was her introduction to the world. The label loved her so much that they were willing to use her on the albums. Soon we needed a second background singer, so I let Dan [Auerbach] know about my granddaughter. He and the label were immediately supportive and have been willing to [incorporate] as much of my family as possible into my career. This is mostly just me trying to open a gateway for them, because they have the potential to be bigger and better successes than me. Or at least it won’t take them 69 years to get discovered.

You’re often referred to as a bluesman, but Black Bayou could also just as easily be described as a gospel album. What are your thoughts on the dynamic between the two genres and how you’re able to tie them together on the record?

The only difference between the gospel and the blues is really the choice of words you use. The same music that you hear in the club is being played in the church and the same music that we grew up on in the church is being played in the clubs. The only difference is that if you want blues you sing “oh baby” and if you want gospel you sing “oh lord.” Other than that, a lot of the rhythms and dances are the same.

What’re your thoughts on continuing to make this type of music in the modern age?

I don’t even look at it as gospel or blues anymore. I look at it as just saying the truth. Regardless of what you’re going through, there’s someone else who’s somewhere who’s been through the same thing. The fact that they made it through gives hope that you can do it, too.

As artists, we’re blessed with fans that will pay to come see you and even take your advice home with them. The same people who go to church will not remember a thing the preacher talked about, but if they like your song they’ll remember it word for word. If you’re really trying to reach people, you’ve got a better chance to reach a lot more folks by singing than you would preaching. Nobody wants to listen to an hour and a half or two hour sermon, but they will stay around a concert for an encore. That’s why it’s so important when you have the world’s attention to tell them something positive with it.

It almost sounds like you view yourself performing on stage like a minister preaching from the pulpit?

That’s it. I can get a bigger crowd than the average preacher even though church is always free, but even then people will flock to the clubs. I’ve also sang “Amazing Grace” in nightclubs and had people put down their glasses, sing-a-long, and go to church with me. You just don’t know what people will do. Everyone’s going through something. If you stop the church people from going to the club then the club will shut down, because most of the people frequenting there are church folks from the other side of town. The problem is that while there they’re not getting the truth. They’re getting the water, but not the wine.

There’s not a better song on the album that ties these influences together than the aptly named “Gospel Blues.” Are you hypothesizing what you’ll do in heaven on it?

I’m trying to tell people not to be so judgmental. That’s why I sing, “I do drink a little whiskey, and I’ll take a little shot of wine” – because it’s better to be real with people than to try and fool them. Whether I have some whiskey [or not] isn’t going to have anything to do with whether or not I go to heaven or hell.

Another song I’ve been captivated by is “Alligator Bait.” Is that a true story?

That song was actually designed more or less as a joke. I never met my grandfather on either side, but I did hear stories when I was sitting around with my dad and his brothers about things like that. It seemed like I had a cruel, cruel grandfather, but that wasn’t the message I was trying to convey. I was trying to prove that any song where you think you’re right needs to be like you just read a novel. It needs to tell a story. It’s more about being a convincing writer than deceiving.

On the cover of Black Bayou is the pond that I used to swim in and got baptized in. For a while it’s just been deserted, but we went back there, because it conjured up a lot of those childhood memories. Even just standing there taking photos my mind flashed back to the things we used to do there like swimming on one end and fishing on the other. Us jumping in the water would scare the fish over to the other side where they could get caught easier, which in many ways is similar to how the alligator is lured in the song.

What has music taught you about yourself?

It’s helped me to find and be myself. I used to try imitating everyone from James Brown to Ray Charles, but soon I realized that the only person I could be the best version of was myself. Nobody can beat you being you. If you just be yourself then you’re automatically different from everybody else anyway. Being real with myself and my music has opened so many doors for me, because of that.

Photo Credit: Jim Herrington