Bassist and singer/songwriter Missy Raines has spent the majority of her life on the road — she began professionally touring with bluegrass bands as a teenager. Early on, she supplied the low end to acts like Eddie and Martha Adcock and Claire Lynch Band, but the greater part of her past musical decade has been spent fronting her own band, the New Hip, and exploring genre-bending terrain on the fringes of bluegrass. Royal Traveller, her brand new album, sheds the New Hip moniker, but keeps the exploration, inspired by the handle of a suitcase and her ever-nomadic life.

But this isn’t an album that you’d simply file away as a musical fulfillment of the “it’s about the journey, not the destination” cliche. It’s an open and honest telling of the realities of a life in transit, a life in flux, in constant motion. The countless miles Raines has traveled are a gorgeous, weathered patina on her songwriting as well as the careful, intentional arrangements — and rearrangements — of these songs. That patina — which we temporarily coined “haggardness,” clearly the word of the day during our conversation earlier this month — is balanced by a hopeful message, youthful joy, and the feeling that, despite that weariness, the album ultimately still looks ahead to what’s next.

There’s a beautiful kind of — and I don’t want this to sound insulting at all — haggardness or road-weariness, this totally relatable human feeling of, “wow we’re still doing this,” in the record. It’s kind of beautiful because it doesn’t feel depressing or downtrodden, it doesn’t drag you down, it feels like a musical sigh of relief. How intentional were you in fostering that feeling — or were you? Do you feel that in the record?

I don’t think it was an intentional “sigh of relief,” but I definitely chose these songs intentionally to say the same thing, hopefully in different ways, which is, “I’m still here. I’ve endured.” And, not just “I’ve Endured” — I chose that song specifically because I’ve always loved the words, I’ve always loved it, and wanted to do some kind of different version of it, but also, I wanted to be able to say, “Here’s a little bit about what’s happened to me through these years.” It’s that feeling like, “It is what it is.” I’m not going to sugarcoat it, it is what it is.

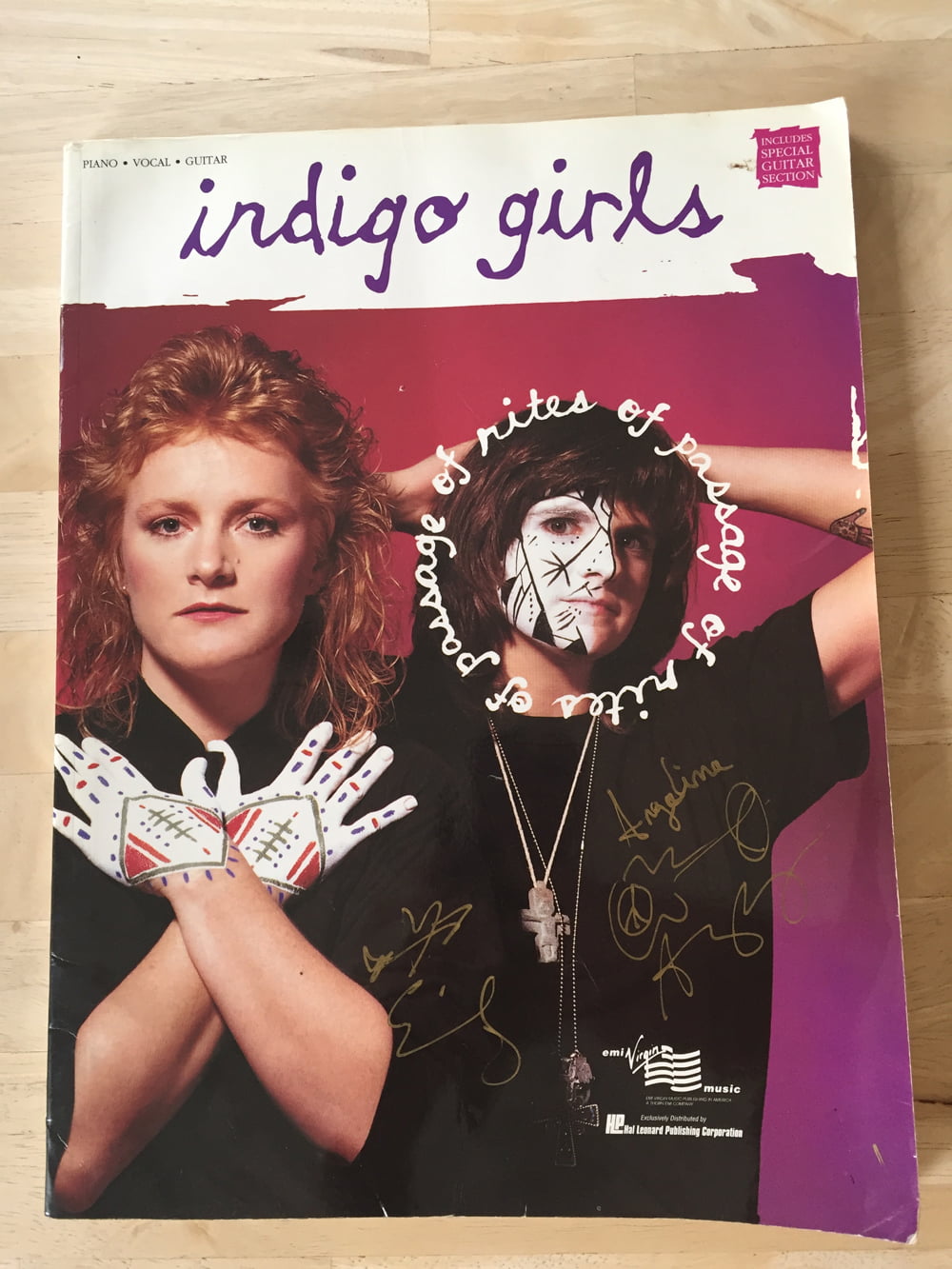

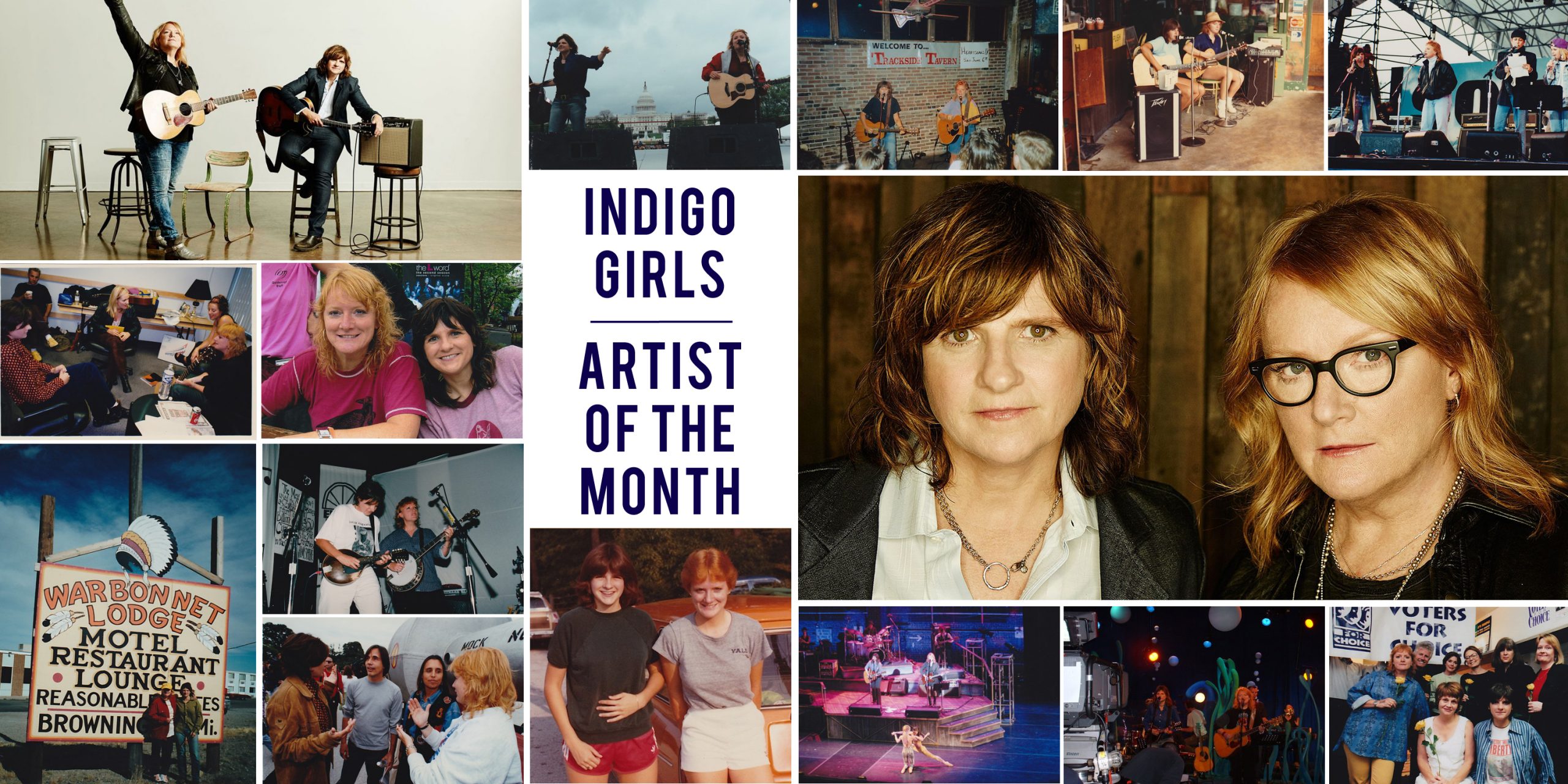

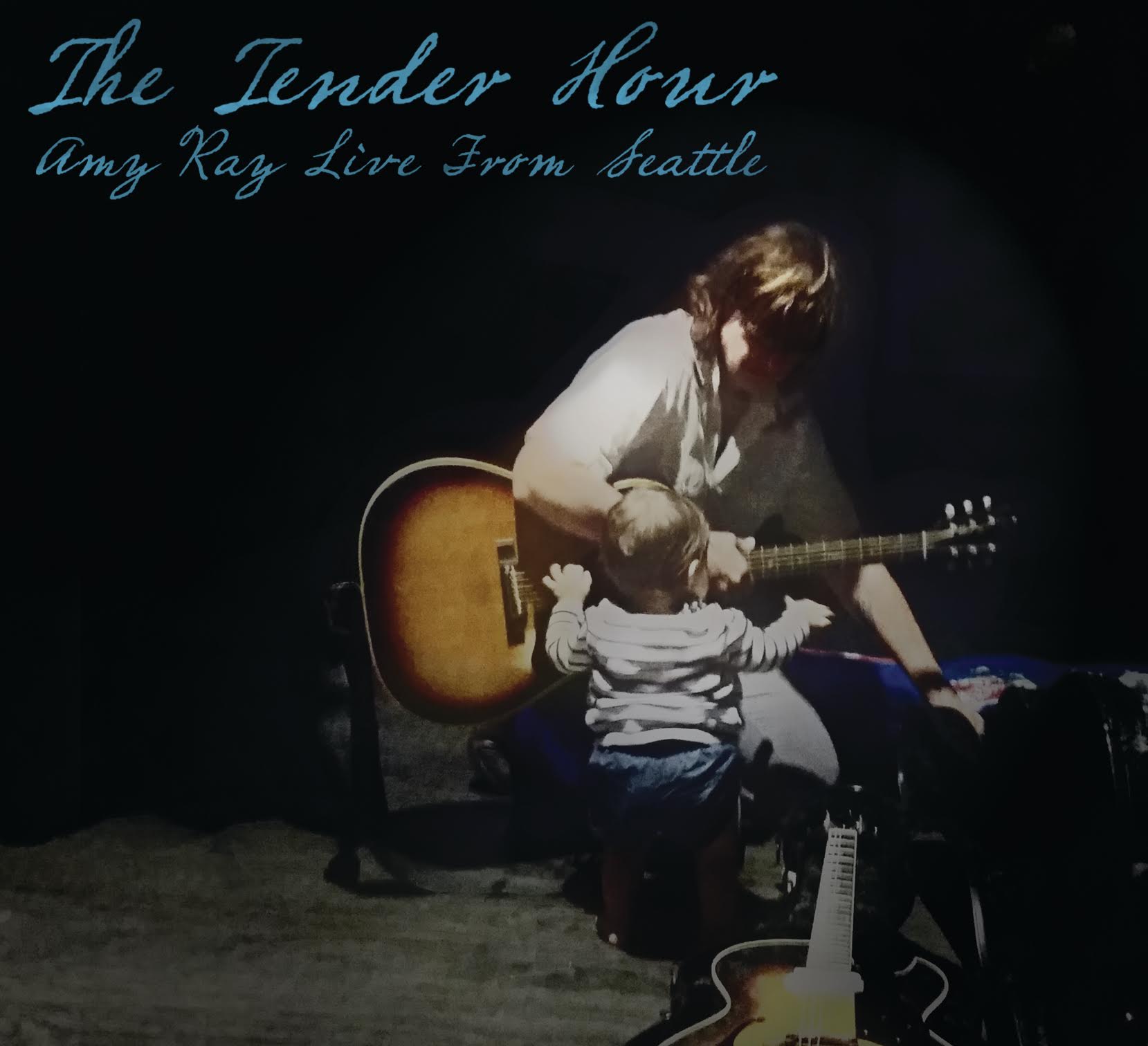

The guests on the album demonstrate, once again, how far your musical travels have taken you. Whether it’s 10 String Symphony or Amy Ray of the Indigo Girls, or your husband, Ben, singing harmony with you. You also collaborate so much across generations. It’s such an important part of bluegrass as a community, but it’s just as important to these sorts of conversations, right? What shaped the process of bringing all these collaborators together on the album?

A lot of it came from different configurations of the band and people I’ve worked with before. A lot of those guys are a generation below me at least. I just wanted them to be part of it. I do enjoy collaborating with people from different generations, I really do. I don’t know that we thought about it like, “Let’s get you paired up with somebody who’s not in your age bracket.” I don’t think we did that in that regard, specifically. I know that I do think about wanting to play music with different people just based on how much I like whatever it is they do.

10 String Symphony was just the obvious choice to do this sort of bowed effect we did on “I’ve Endured.” I get so much out of playing with younger people. It’s a kick in the butt. It makes me want to keep playing. I feed off of that, I feed off of the people I’m around, the band that I tour with, when they have this freshness and this eagerness and joy. I still have joy, but I know that I can’t help but be jaded in certain ways and maybe cynical about certain things that they aren’t. It’s interesting to hear from their perspective and it helps me to maintain what I’m doing every day, because I’m getting this input.

Touring with those younger, joyful people is the perfect balance to that haggardness we were talking about, so the music doesn’t strike listeners as beleaguering or at the end of a long, tiring road. Even at the end of all these journeys, the music still sounds like it’s not retiring, it’s asking, “What’s next?”

That’s how I feel. I’m at the point in my life where I have definitely done a lot of miles and done a lot of things, but I’m in no way finished. It feels exciting to think about what the next thing is. I’m thinking about that and excited by that and ready for it. Yes, being around younger people feeds that, to me. I want to learn from them, I want to know who they’re listening to, I want to be turned onto things that I normally might miss, because I just can’t keep up.

We’re all in our little bubbles. I want to hear what their bubbles are. And on the flipside, I like hearing how young people are viewing how they’re struggling. I don’t mean to say just because they’re young doesn’t mean they don’t have struggles, I like hearing how they deal with their struggles. It helps me keep my shit in perspective. We’re still all fighting and we’re all moving in the same direction and that’s really empowering.

I hear your activism in the album as well; it’s simply you, your ethos, and your worldview coming through the music. You’re not only collaborating with all these women, but your deep pride in Appalachia shines through as well. You don’t fall into the trope of a downtrodden, helpless, bleak Appalachia and South. I wonder if this has been a conscious decision, to opt for this sort of hyper-personal approach to your activism, or is it subconscious, just you being you?

I’m just inspired by the fact that there are so many amazing women, both in my generation and coming up behind us, and the ones who came before, too. I’m inspired by the young women, by the women who are my age and kicking ass, and the women who are older than me who keep kicking ass. I’m also so encouraged and feel positive and excited and happy — I can’t find the right word… content. Not content with the way things are, exactly, but content with the fact that it is changing. I’m content that we are on a path. Things are changing. And that my nieces and grandnieces that I have are not going to be in the same world that I grew up in.

And I think it’s just me being me. I don’t think I’ve ever had anything together enough to make a plan that could’ve been contrived that well. [Laughs]

But see, I think that that’s why your music, and that more subtle activism, is so effective, because it’s not overwrought.

I appreciate that, I had tried to make those kinds of important decisions come from my gut. It sounds cliche, but it’s really true. The times that I haven’t done that, when I’ve done things that I’ve felt were what I should do or what would go over better, I’ve always regretted those decisions. When I’ve leaned back and allowed my gut to take me, it’s always been a better feeling and it’s always worked out better in the long run.

It’s interesting that you bring up the heritage and the Appalachian thing, because a few people have said this to me anecdotally or from fans, they’ll come up to me and say, “I can tell you’re such a proud person from Appalachia from this record.” I can tell you that that is the absolute last thing that I was going for. I feel that I am that [proud] person, it’s not disingenuous, but that wasn’t in my thoughts at all. All I was trying to do was to capture a bit of my story.

With “Allegheny Town” I just went to the feelings I get when I go back home, because I get all these really weird feelings when I go back home. I was trying to capture all of that in all of this — in “Royal Traveller,” in “So Good.” I leaned on a lot of visual images [of home] while I was writing this stuff. It’s fascinating to me that people are getting this from this! I’m thrilled, because when you’re not actively trying to get something across, but it is part of what you feel and part of who you are, it feels good when it’s worked.

You’ve played our Shout & Shine showcase at IBMA twice now. It’s not the first or only movement there’s ever been for inclusion in bluegrass, which is important for the record to reflect, but there is this new movement for diversity and inclusion in bluegrass and I wonder what you think, watching this unfold and being a part of it, after being in this community for your entire life and your entire career?

It fills my heart with joy. It’s like the fulfillment of something. Something that had been so missing is now being filled. It’s not completely full, you know–

But the spigot is on.

The spigot is on and I’m just thankful that I’m still alive and that it happened within my lifetime. I’ll hopefully be around for a lot longer, but to know that it’s happening feels like — you know, I’ve often talked about bluegrass is my family. It’s more than just music, it’s literally the family and community that I have chosen to be in. I don’t know where I leave off and where bluegrass begins, I really don’t. Despite all of my explorations into other kinds of music and my fascination with other kinds of music, I say I am bluegrass. I am of bluegrass.

It’s not where I end, but it does define the core of me. Without the community it’s nothing. It’s like being at a family reunion that lasts all year long. You’re at the family reunion and you’re sitting there, and you’ve just eaten a bunch of things, and you’re sitting with all your favorite people, but then you look over here and you see that two facets of the family that haven’t been speaking are now talking to each other. And you’re just filled with joy cause the family’s coming together more, becoming stronger.

All of a sudden it’s like a Fellini movie, people are hanging off of chandeliers and riding Ferris wheels that weren’t there a second ago, and we’re all just playing together. Because another link just got connected. That’s how I feel. We’re all in this family reunion where in the past, people wouldn’t have been connecting, and now that’s all starting to change. It makes me very, very happy. It’s an inexplicable feeling because it’s so important to me. I’m just happy to be a part of it.

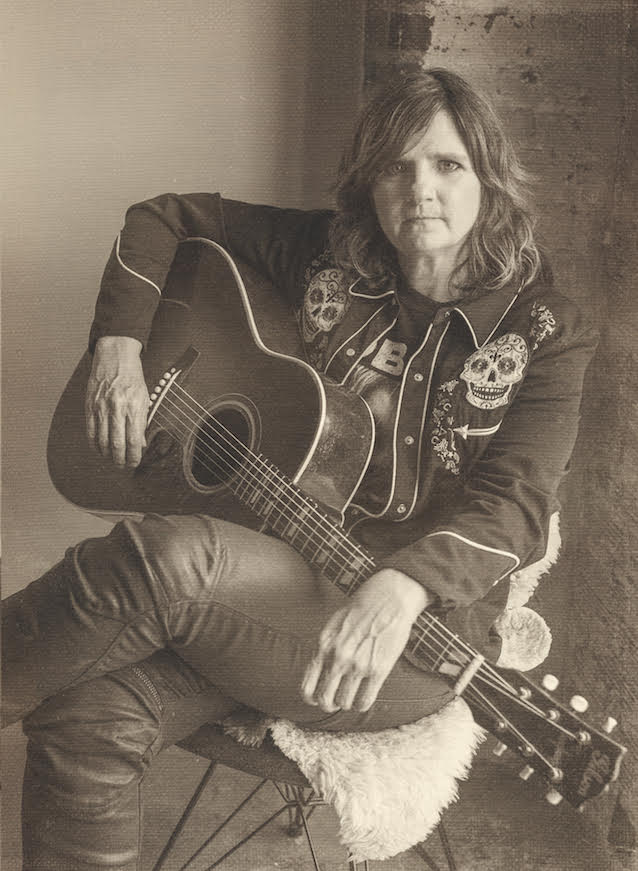

Photo credit: Stacie Huckeba