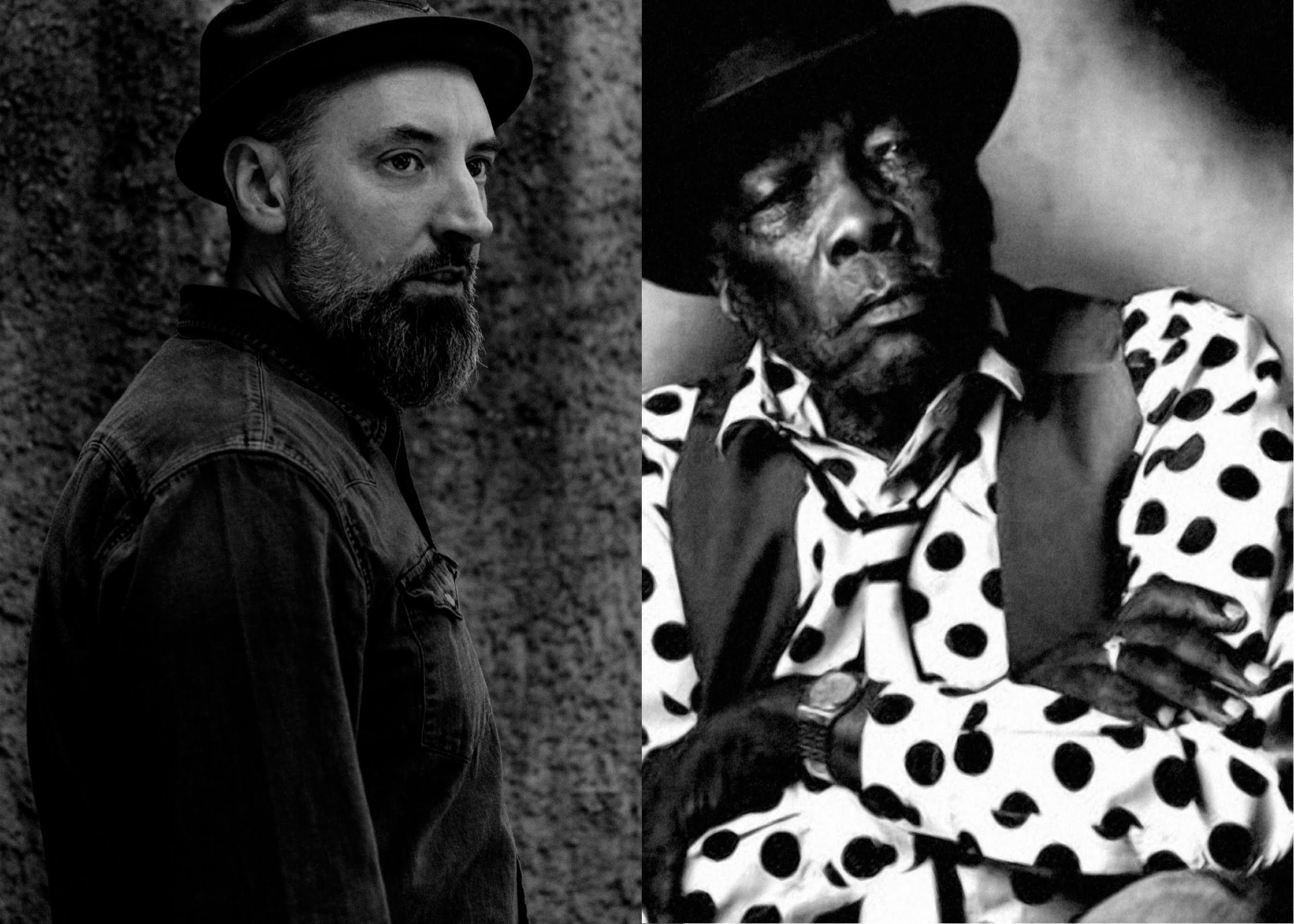

While putting the finishing touches on my new record, At First There Was Nothing, I found myself living beside the tracks of the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge Railroad in southwestern Colorado. Widely considered one of the most scenic train trips on the continent, the jaw-dropping route stretches 45 miles through pristine wilderness, along impossibly narrow cliff ledges, and above roaring river rapids.

Though it was originally constructed in order to haul gold and silver ore from the otherwise inaccessible San Juan Mountains, these days it’s a tourist line beloved by sightseers, backpackers, and whitewater rafters. Even though the cargo has changed, the railroad is still powered by steam engines, just as it was 140 years ago when it first opened, and it’s hard not to fall in love with the sights and sounds and smells that go with it.

When it came time to make a video for the album’s lead single, “Long Haul,” I knew that I wanted to find a way to bring the railroad into it, and fortunately they were gracious enough to let us commandeer a caboose for the finale.

Returning to Durango for the project had me thinking about the strong connections between music and railroads. For as long as there have been trains, there have been train songs: some are joyful celebrations, others, mournful laments. A train whistle can mark a long-awaited arrival or a much-dreaded departure, the start of a new adventure or the end of the good old days. It’s hard to know where to begin when it comes to putting together a playlist of railroad songs, as trains have been written about from nearly every angle in nearly every genre, but here you’ll find some of my favorites, which I hope may inspire you to hit the rails yourself. — Anthony D’Amato

The Band – “Mystery Train”

A cornerstone of American rock and roll, “Mystery Train” has been performed and recorded by just about everyone over the years, but I chose to kick things off with The Band’s version. Musicians use the term “train beat” to refer to a certain kind of basic drum pattern, but Levon goes above and beyond here. There’s a relentlessness and a momentum to his groove that genuinely evokes the feeling of wheels rolling down the track, and it’s utterly mesmerizing.

Howlin’ Wolf – “Smokestack Lightnin’”

Eerie and hypnotic, “Smokestack Lightnin’” is an all-time blues classic. Howlin’ Wolf said the title was inspired by sitting in the country at night and watching sparks fly from the smokestack of passing trains. Close your eyes while you listen and it’s easy to see the red-hot embers dancing in the empty black sky.

The Kinks – “Last of the Steam-Powered Trains”

The through line from Howlin’ Wolf to The Kinks is pretty obvious when you listen to these songs back to back.

The Staple Singers – “This Train”

There are a whole host of versions of this song to choose from, but I’ve always loved The Staple Singers’ take on it, which blurs the lines between gospel and blues. The train is a potent symbol not just in 20th century music and art and literature, but in religious expression, as well, and this is a prime example.

Bruce Springsteen – “Land of Hope and Dreams”

Springsteen references a number of train songs (including “This Train”) within “Land of Hope and Dreams,” which was a live favorite for years before he recorded it on the Wrecking Ball album. I’ve always been drawn to the imagery in this tune, as well as the intricate way in which the words all fit together like puzzle pieces without a single wasted vowel or consonant. “Big wheels roll through fields where sunlight streams” is as clean a line as you could ever hope to write.

Elizabeth Cotten – “Freight Train”

Written when Cotten was still quite young, “Freight Train” is an enduring classic more than 100 years later, and her performance here is utterly timeless. Interestingly enough, the tune made its way to England in the 1950s, where it was covered by a skiffle group called The Quarrymen (which eventually evolved into The Beatles). Seems everyone cut their teeth on train songs.

Lead Belly – “Midnight Special”

The passing headlight of a train is a sign of freedom and salvation for a prisoner in this song, who lets the glow wash over him like baptismal waters in his penitentiary cell.

Ernest Stoneman – “Wreck of the Old 97”

Trainwrecks have been fertile ground for songwriters through the years, and who could blame them? Trainwrecks have it all: drama, heroism, danger, tragedy, sacrifice. If all we got out of this tune was Rhett Miller and his compatriots in the Old 97s, it’d still be worthy of inclusion here.

Woody Guthrie – “John Henry”

Railroads have produced their fair share of local and regional folk heroes over the years, but none as iconic as John Henry, who wins the battle of man versus machine but pays with his life. There’s a whole lot about capitalism and labor and race and technology all wrapped up in this song, which could be said of the railroads themselves, too.

Bob Dylan – “Slow Train”

There’s a simmering intensity to this song that stares you dead in the eye and refuses to blink. I don’t think it’s any coincidence that Dylan chose a train as the central metaphor in this scathing assessment of America.

Arlo Guthrie – “The City of New Orleans”

Steve Goodman’s “City of New Orleans” is another well-covered train song, but as far as I’m concerned, Arlo Guthrie has the definitive version. It’s a beautiful slice of life from the perspective of a traveler looking out the window at a changing country.

Justin Townes Earle – “Workin’ for the MTA”

It’s hard to write a modern train song that doesn’t sound like Woody Guthrie cosplay, but Justin Townes Earle did a brilliant job of updating the form on this tune, which is sung from the perspective of a New York City subway worker.

Amanda Shires – “When You Need a Train It Never Comes”

This one’s about a lack of trains, but I think it still qualifies. This was the first song of Amanda’s I ever heard, and I was instantly drawn to her unique perspective on what could otherwise be well-worn territory. Like the Justin Townes Earle tune, it’s a rare contemporary take that feels genuinely original.

Brad Miller – “Reader Railroad No 1702 2-8-0”

This might be considered cheating since it’s not technically a song, but over the years there have been a number of LPs released by and for railfans that consist entirely of field recordings of trains. Many have been relegated to attics and secondhand shops, but some were digitized and made the leap to streaming. I chose this recording from a 1972 album called Steel Rails Under Thundering Skys because I think it offers a great entry point to someone asking the perfectly reasonable question, “Why the hell would I want to listen to that?” The mix of steam trains, falling rain, and rolling thunder is incredibly soothing. Put it on and watch your blood pressure drop.

Photo Credit: Vivian Wang