When Maya de Vitry quit her most recent full-time touring gig, she did it for self-preservation. Before her solo debut Adaptations was released in 2019, the multi-instrumentalist and singer/songwriter prioritized her life by centering community, home, and a sense of place in what had often been a frantic, taxing, and nomadic daily life.

Her second, just-released album, How to Break a Fall, was tracked almost immediately after Adaptations hit shelves, and with a harder, more grizzled, rockier aesthetic it demonstrated the growth and transformation that had occurred in the meantime. A sense of movement, of excited, unapologetic momentum permeates the Dan Knobler-produced project. Where Adaptations had seen de Vitry through a transition to stillness, How to Break a Fall was poised to carry her into still another new period for the budding solo artist.

Enter a global pandemic. With nearly all of that momentum and her entire release cycle squandered on a music industry that had to shutter itself in the face of COVID-19, de Vitry found herself once again prioritizing, enjoying each individual moment at home, focusing on community in whatever shape it can take at this point, and baking banana bread, too. It turns out practice does make perfect.

BGS spoke to de Vitry over the phone, immediately diving into how serendipitous this collection of songs is for a moment of global pausing.

BGS: The last record, Adaptations, was written in isolation and now you’ve landed with this new record, How to Break a Fall, and on the back end of it you’ve ended up in isolation again. I wondered if you’ve thought about that? Or considered the strange symmetry, the way that these records are bookended by the idea of intentional solitude?

de Vitry: [Laughs] Wow, I absolutely did not connect those dots and that is so wild. It’s so ironic, because I was feeling very frustrated and angry about losing all of these shows this spring and I was finally feeling like [I was ready to get on the road] — because with Adaptations I didn’t tour really at all. I wasn’t emotionally or mentally healthy enough to be touring my music, I wasn’t ready to be on stage. Then this time, I felt emotionally healthy to go out there and play shows and it was like, “Oh, but the world has another health situation going on.”

In some ways, How to Break a Fall was also written in isolation. I had kind of cut myself off a bit from the East Nashville scene, because I needed some space from the patterns and circles of people. I needed space from touring and leaving [the Stray Birds]. I was working at Starbucks while I was writing the album and I was essentially in isolation. You go to work for eight hours, come home, and you’re just in your house again. It was still voluntary, and I definitely still had some community. I could still pop out and play a show.

I’m kind of an introverted person, so I’m always in isolation when I’m writing — in some way. I’ve been writing so much in the last couple of weeks. I was ready to kind of emerge, I was ready to go and be out there, and in interaction, instead of isolation. Now it’s like mandatory isolation and I’m going to write.

What does that feel like to you? Does it feel like a grinding of the gears? Like, “Oh, hold on, we’ve gotta turn this ship around and it’s going to take some effort and energy for me to go back into the writing frame of mind when I was ready to be in the outward-facing, extroverted frame of mind.”

It feels like muscle memory. It’s like a pivot. That part of it has not been difficult. I think accessing the writing part, the inward part of being an artist, is [always] within reach. I get as much satisfaction from creating the stuff as I do performing the stuff, if not more. I would say the process of writing an album, recording an album, and being in the studio with people is so fulfilling to me. Just creating it. There’s almost a grieving process when that’s over. Then there’s the next thing, when the songs come alive… I was looking forward to that, seeing how the songs would live and evolve and change. How they would land, out there in the world in real time with people. What other choice do I have? Let’s just pivot. Let’s write another record. [Laughs]

“Better and Better” is about the idea of building something and the song feels pertinent in this moment of… pausing, let’s say, because I think we could all eventually agree that life isn’t about being the best, it’s about being better. It’s about being better than the moment before, the day before, the year before. How do you see that song’s potential for connecting with listeners right now?

That song was like the doorway for writing the rest of that album and it was the doorway because, through writing it, I was realizing that I was actually unwell. Some of the things I was singing about, those lyrics were all things that I wanted to believe, and I realized that I had to make changes. I had to stop doing something that felt normal. I had to leave the band that I was in, I had to stop touring for a while, and yeah, that in some ways does remind me of this moment, too. The only thing we really can control right now is how we take care of ourselves — and that’s also sort of the only thing we ever can control. But it’s easier to feel that when it feels like other things are so outside of our control.

I felt myself stop, stock still in the moment that I heard the line, “Forgiving myself is the most I can do” go by, because I don’t think a lot of people realize that’s what we’re doing every day right now, to get through. Letting ourselves just be enough. Where does that line come from for you?

That line is specifically about staying. About staying in the situation I was in. Before I was in [the Stray Birds], I was a musician. I was playing fiddle tunes, I was really into old-time music, I was writing songs, and I started to draft up what would be a solo record — in like 2009 and 2010. Then the band became like an invisible fence. There was no room for anyone to be doing anything outside of the band. There was no physical room, for all of the time we were on the road, and there was no emotional room with the interpersonal dynamic of the band. It was not possible to continue to be myself, to nurture my own voice as a writer and musician and also be a member of that band, because of the environment of the band.

Forgiving myself, in that line, is about forgiving my nineteen-year-old self for not knowing any better at the time. And forgiving myself for my fears, because it was easier [to avoid them instead]. It’s vulnerable to sing your lyrics at all, ever, and I’m forgiving myself for those fears I had. Instead of standing up with my name and my lyrics, it was easier to climb inside the identity of a band and feel protected and more secure.

Which is quite the contrast from How to Break a Fall, because, to me, this record feels like a statement, a declaration for women to be allowed to take up space. And to be allowed to access and enjoy as much of the oxygen in those spaces as they like. Songs like “Something In the Way She Moves,” “Gray,” definitely “Open the Door” all speak to this. And the rock ‘n’ roll aesthetic often feels angry and impassioned, but the music doesn’t feel hostile in the way that it channels those energies.

That’s one hundred percent right. That comes from that process of forgiveness. It comes from walking through that doorway, the doorway being “Better and Better,” and walking into this landscape of songs and being receptive to writing that story. I think the record doesn’t sound hostile because it’s not. These are the songs, these are the sounds that I felt like making, this is a story. These things are true for me.

There’s this video of Sister Rosetta Tharpe playing incredible guitar, walking up and down this train platform, it’s an iconic taking-up-of-space. An iconic expression of joy. That kind of spirit is what’s behind this music and this record. For as much as I can control what people can get from it, I would hope that some of what it unlocks or awakens is, “Huh… there are a lot of female characters on this record taking up space and doing what they want.”

It’s not hostile because it’s taking the responsibility of going inward by going to my own interior and inviting listeners to go into their interiors and see what’s going on in there. In the song “Revolution” it’s like, What are these walls? What’s inside of me? If this is the way that my eyes have been trained to see, what new world am I going to see? If I can’t shift the lens or something on the inside, how am I going to see a world that’s [different?] It’s happened so many times in history, whether it’s women’s rights or gay rights or the civil rights movement. We have to practice imagining the impossible. That’s connected to why it’s not hostile.

When that’s the reason behind the music and the intent behind the record, the volume of it or whether it’s an electric or an acoustic guitar or if it’s rock or folk — none of that matters to me. [Laughs] This is the story I’m telling!

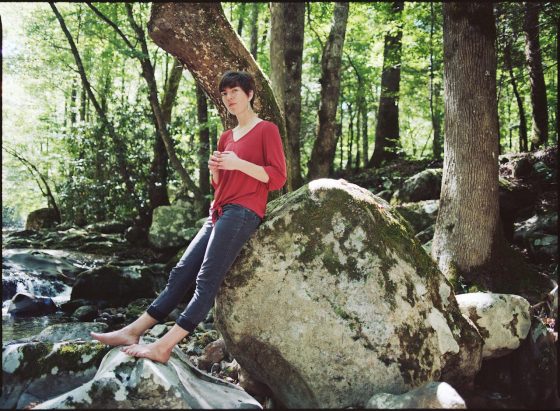

All photos: Laura Partain