Rod Picott writes from the heart, and that’s particularly true on his new album, Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil. A frightening heart condition – mercifully caught just in time – shifted his songwriting perspective inward, resulting in 12 news songs recorded with merely an acoustic guitar, a harmonica, and a storyteller’s voice.

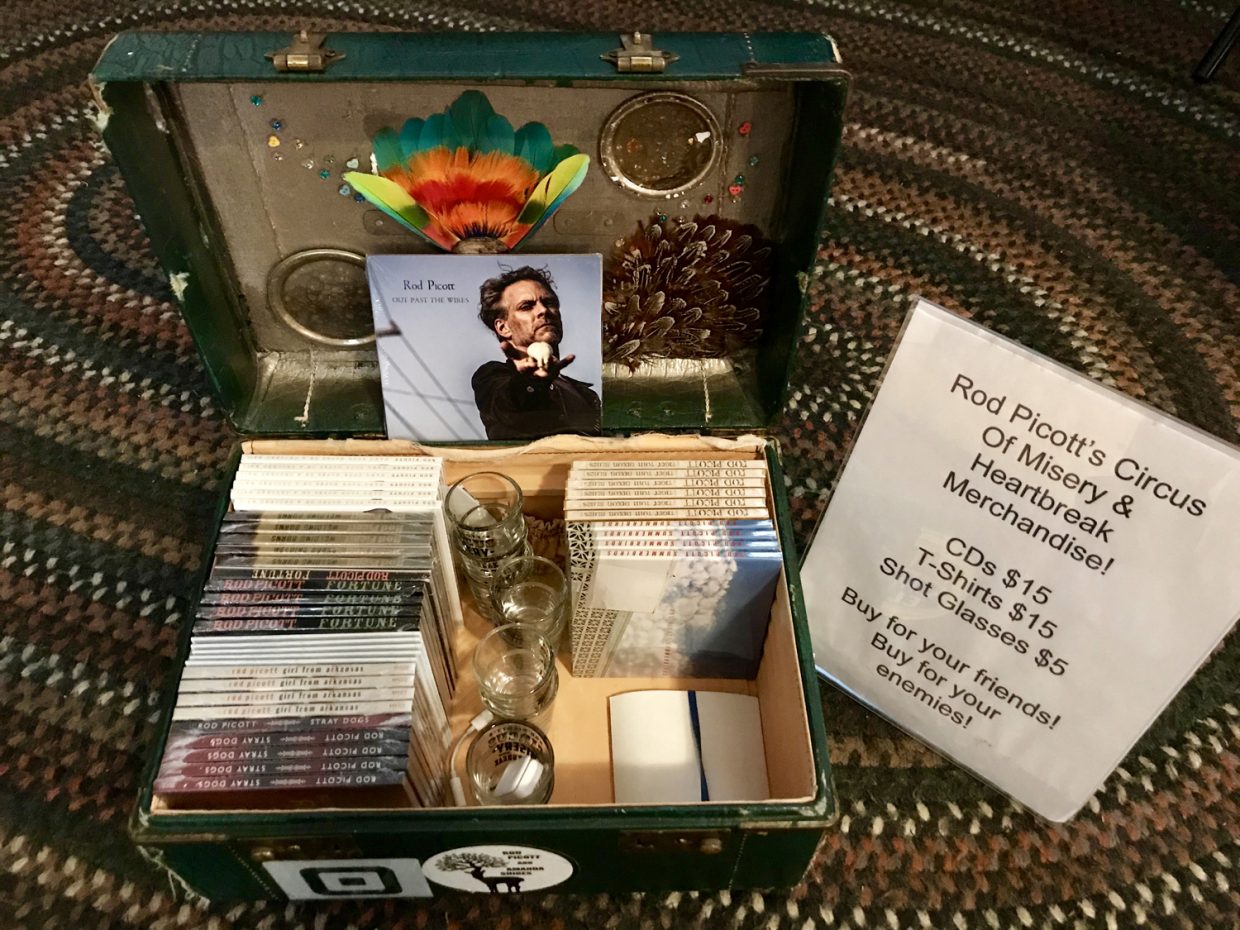

That’s a familiar set-up to anyone who’s seen Picott perform over the last 20 years. The Nashville-based songwriter released his first album, Tiger Tom Dixon’s Blues, in 2001, and he’s toured almost constantly since then. While most of his albums are fully produced, Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil is almost whispered in places, inviting listeners to lean in.

Lately, Picott has turned his attention to writing fiction, poetry, and a screenplay, but music remains a central theme of his life and career, clearly evidenced by a conversation in a Nashville coffee shop.

BGS: I’m curious about the song “Ghost,” because it describes somebody who seems to be at the end of his rope. What was on your mind when you were writing that song?

RP: I was in the middle of [the health scare] when I wrote that one. I did feel there was a time during the making of this record where I thought it’s possible that this will be the last record that I get to make. And if that’s the case, what do I want to say? How do I want it to be? I realize that sounds dramatic, maybe overdramatic, but when you’re in the middle of it, it sure doesn’t feel like that.

Because you thought you weren’t going to live? Or you weren’t going to be able to sing?

Didn’t know. I mean, I knew something was wrong and I knew it had something to do with my heart. My blood work came in. The doctor called me at night. Of course they don’t do that. He’s the on-call guy and he basically said, “You need to stop whatever you’re doing right now. You need to drive to the pharmacy and pick up this prescription. I’ve already called it in. They’re waiting for you.” He said, “You need to do it right now or you might not make it through the night, because your potassium level is so high, it’s messing with the electrical signals to your heart.” A simple thing like that — potassium levels. Who would know? They eventually got it figured out.

Did it affect the way you sing, or your singing voice in general?

I was weaker when I was recording, to be honest with you, which might have played a role in how intimate the recording sounds. I’m singing pretty quietly on most of the songs. Not all of them, which is counterintuitive because the quieter I sang, the bigger it sounded, which is very strange. It’s like cinéma-vérité, like I’m actually living the thing that I’m singing about, and it’s playing a role in how I’m singing.

I can hear some of that, but it’s not like this album has 12 songs from the brink of doom.

No, no, there’s a range. And there’s one song from 20 years ago, “Spartan Hotel,” which never fit in any of the other records, but it felt right for this record. There’s a handful of songs I still like from back then, but they just haven’t fit on a project.

On “Mama’s Boy,” you’re singing about boxing and it reminded me of “Tiger Tom Dixon’s Blues,” from your debut album. What’s your relationship with those older songs now? Do you still like to play those songs from the early records?

I’m still proud of them, yeah. I still play those songs from that first record. I wish I could redo the performances now, because I think I’m a better, more honest singer than I was then. But when I moved to Nashville, or even before I moved, I promised myself I wasn’t going to make a record until I had 10 songs I thought were worth people hearing. So that served me well, even though it took me a long time to get there. That first record, the songs themselves still hold up. I still play them all the time.

What was it like for you to move to Nashville in that era? What was your impression of it here?

I was married at the time and obviously my wife came with me. I’d never been to Nashville. I didn’t know anybody that lived in Nashville. I didn’t even know anybody who knew anybody who lived in Nashville. So it was completely blind. We got a hotel downtown and went for a walk. And of course, in 1994, half of downtown was boarded up, old porno shops and stuff.

At one point on the walk, we were looking for a restaurant. You couldn’t even find a single restaurant. We couldn’t find any place to eat. She just stopped and started sobbing: “Why did you bring me here?” [Laughs] But over the next six months or a year, I figured out the lay of the land. Playing a lot of open mics, and meeting other writers and really working hard at trying to decode how the town worked.

How did you found your tribe? Just going out to open mics?

Yeah, for sure. That was a big part of it. And writers nights where they would have a little 20-minute spot, as opposed to just getting on the list. Those were better, kind of playing a mini set. It was a huge learning curve. I loved to go into the Bluebird Café. I used to go to the early shows at the Bluebird right after work and sit at the end of the bar. I was one of those classic guys with a notepad, which is really annoying to other songwriters, because they feel like you’re stealing the song. Which I wasn’t, I was just making notes about what worked and what didn’t. It was wonderful. Soon after that, I realized Nashville had John Prine, Lucinda Williams, Gillian Welch, and Guy Clark, and I thought, OK, this gives me a marker to shoot for.

In your work, there’s often a theme of your family and a theme of a work ethic — and a lot of times they’re in the same song. Is that something that was instilled in you?

I think it’s just you write what you know. That really defined my childhood. My father was a solid, blue collar union guy, in the pipefitters union. He was a welder and surrounded by other really hardworking men. So I’ve always been really interested in that, because I was a slightly unusual kid. I was very sensitive, which didn’t work with my father’s personality. I don’t think he really knew what to do with me. Now I can look back and see the kid that’s me, and I can think, “Well, now I understand it. I was an artist.” But I was just a kid. I wasn’t there yet, so it was a very uncomfortable relationship for a long, long time with my father.

I’ve always been interested in those themes. Also I was in the construction world for a long, long time, for almost 20 years. I was a sheetrock hanger and finisher. Having an artistic nature and working in the construction world is a very, very tricky balancing act. I had to learn how to be tougher, which wasn’t my nature, really. I learned when you had to stand up for yourself and not get run over, but it was uncomfortable. I always felt like I had one foot in the arts and one foot in this working world. I took it seriously and I was really good at it. I loved walking out of a job and seeing those clean lines and knowing I did the best I could, and that the painter was going to have a really easy time with the job.

That’s pride in your work.

Yes. And that’s part of your inner makeup. That’s either there or not. It’s not something you can fake or create.

You’ve been doing making music as you’re living for a while now. What’s your secret?

You almost have to be in a state where you can’t not do it. I do remember having a really specific moment before I put the first record out. I was 35 years old and I had been in Nashville for six years then, I guess. I did have an afternoon where I had this sort of “come to Jesus” moment where I thought, “Man, if you’re not going to do it now, you’re not going to do it. Like, today. You start today.” I remember the feeling coming over me, and it was almost like panic, realizing that I hadn’t started yet, not really. I was learning and I was working hard at it, but I wasn’t really committed to it. I was sort of testing it to see if I could do it. That afternoon, I committed to it and I never looked back.

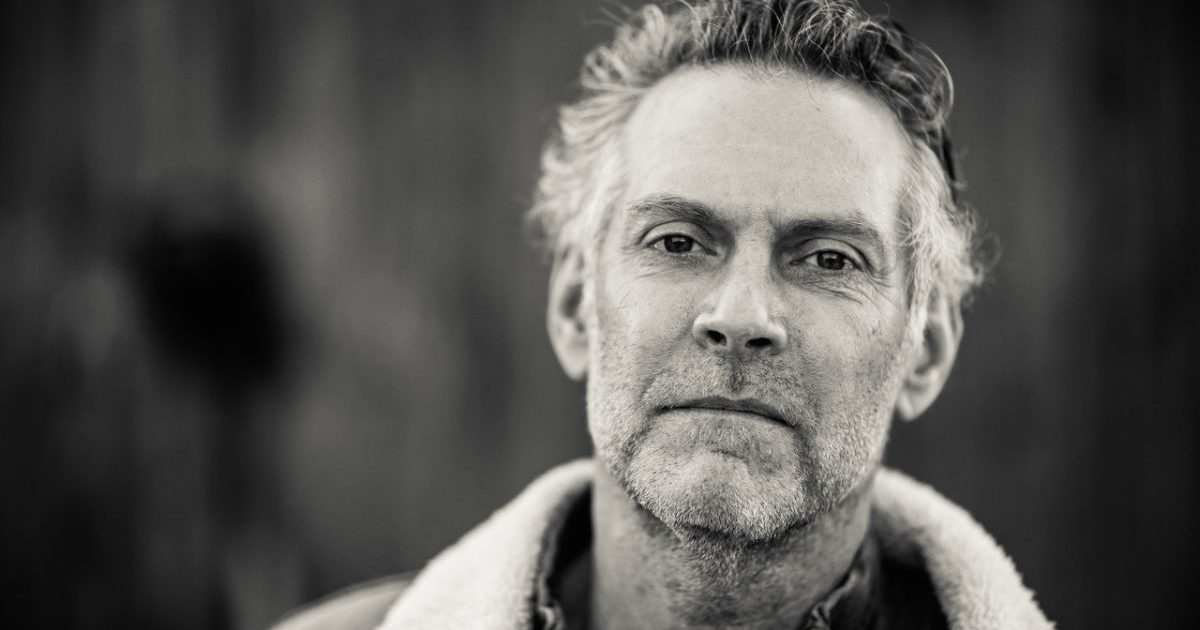

Photo credit: Stacie Huckeba