(Editor’s note: Read part one of Neil V. Rosenberg’s Bluegrass Memoir on the Earl Scruggs Celebration of 1987 here. Read part two here.)

Boiling Springs, NC on Saturday, September 26, 1987: My workshop in the Gardner-Webb College Library with Snuffy Jenkins, Pappy Sherrill and the Hired Hands ended at 4:30 that afternoon when Dan X. Padgett presented Snuffy with a hat. From my diary:

Afterward I hung around and listened for a while to the Hired Hands’ young banjo picker Randy Lucas play the Bach “Bourrée,” “The Stars and Stripes Forever,” and another classical piece expertly on the banjo.

Here’s a nice example, from Bill’s Pickin’ Parlor, of Randy’s recent work in this milieu:

I went for some barbecue (big regional difference thing — this barbecue was red, vinegary; with shredded pork) with Tom [Hanchett] and Carol [Sawyer] and then was kind of enticed away by Dan X Padgett…

I’d met Padgett the afternoon prior, when I first arrived in Boiling Springs; a respected local banjo elder, he was the teacher of the young banjo player in Horace Scruggs’ band whom I’d met earlier today. Padgett had a long and interesting career, with deep connections to Earl Scruggs and Snuffy Jenkins, as well as memories of an earlier generation of banjo greats. He was interviewed for the Earl Scruggs Center by Craig Havighurst in 2010.

…to his car (an old Cadillac) to look at various memorabilia like photos of him with various important country and bluegrass people. He also showed me a very worn copy of the very first F&S songbook and when I expressed a strong interest in copying it he loaned it to me. I also talked with him about the possibility of obtaining a banjo like one he played during the afternoon, a miniature Mastertone about the size of a mandolin with an actual tone ring, flange, and resonator. He said he’d see about it and we ended up standing at his trunk trying out various instruments.

I was picking away on “St. Anne’s Reel” when I noticed there were some people standing around me, and when I finished and looked around there was Doug Dillard looking at me with that big smile. Quite an introduction!

In an edition of the Shelby Star a week or so earlier, Joe DePriest wrote of Dillard’s association with Earl Scruggs, telling how in 1953 the Salem, Missouri teen first heard “Earl’s Breakdown” on the car radio. It hit him so hard “he ran off the road into a ditch.” Dillard got his folks to take him to Scruggs’s Nashville home. “We knocked on the door, and he came, and we asked him to put some Scruggs tuners on my banjo. He invited us in.”

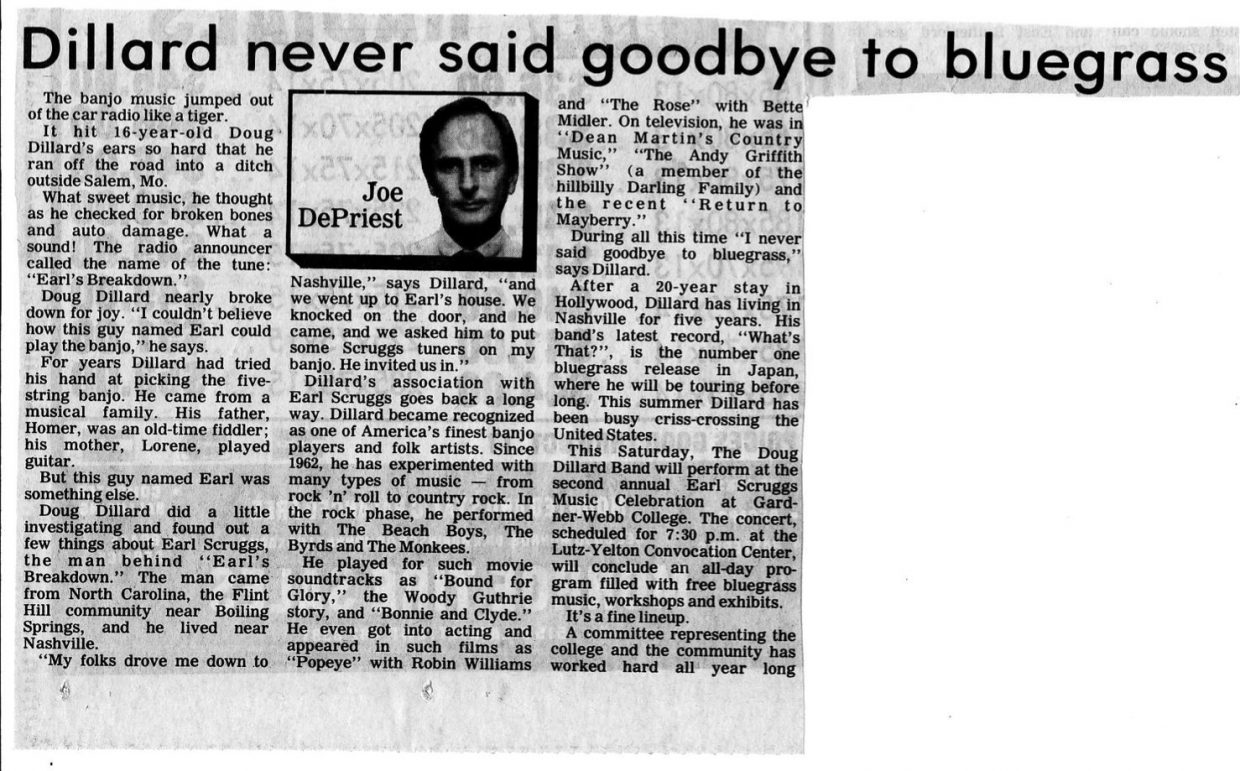

Earl welcomed banjo pickers to his home, especially if they wanted Scruggs Pegs. In the “Suggestions for Banjo Beginners” on the first page of Flatt & Scruggs Picture Album — Hymn and Songbook from 1958, Earl invited those interested to contact him in Nashville, and many did:

In 1962 Doug and his brother Rodney went with their band The Dillards to LA, where they were “discovered” at the Hollywood folk club The Ash Grove. With best-selling Elektra LPs, they toured extensively in the West and appeared on CBS’s The Andy Griffith Show as “the Darling Family.”

In 1966 Doug left The Dillards and ventured into what would soon be called “country-rock,” touring with the Byrds and forming a band with former Byrd, Gene Clark. Dillard’s banjo playing had been strongly shaped by his close listening to Scruggs. In the ’60s when players like Bill Keith and Eric Weissberg were pushing banjo boundaries in bluegrass, Doug was pushing boundaries in a different way by finding a place for Scruggs-style banjo in rock. He fitted solid, straight-ahead rolls into pieces like Gene Clark’s “The Radio Song”:

DePriest’s article quoted Dillard: “During all this time, ‘I never said goodbye to bluegrass.'” He moved to Nashville in 1983 and started a band.

The bluegrass music business was booming in Nashville. A bunch of young pickers were there, touring in bands and doing studio sessions. New Grass Revival featured newcomers Bela Fleck and Pat Flynn; John Hartford, Mark O’Connor, Jerry Douglas — all were in town. The Nashville Bluegrass Band started in 1984; that year Ricky Skaggs won a Grammy for his version of Monroe’s “Wheel Hoss.” Up in the Gulch district, between the Opry and Vanderbilt, the Station Inn was serving bluegrass seven nights a week.

I was introduced to the Doug Dillard Band this afternoon right there where Dan X Padgett and I had been jamming. His four-piece outfit drew from a pool of talented bluegrass musicians.

Rhythm guitarist, vocalist and emcee Ginger Boatwright was a seasoned veteran. During the ’70s she’d toured and recorded with Red White and Blue(grass), and later formed The Bushwackers, an all-female group that began as the house band at Nashville’s Old Time Picking Parlor. Her story is told well in Murphy Hicks Henry’s book Pretty Good for a Girl: Women in Bluegrass. Henry calls her “The first ‘modern’ woman in bluegrass” alluding to her folk revival roots, her styles of humor and dress, and, most importantly, “a softer, smoother, more lyrical quality” of singing.

Having a second guitar as a regular lead instrument in a four-piece band was uncommon at this time. When I met Doug’s young lead guitarist I was surprised to discover he was the son of Lamar Grier, whom I’d hung out with twenty years earlier when he was a Blue Grass Boy. David Grier was 26. He’d studied the lead guitar work of Clarence White (there’s a photo of him with White in Bluegrass Odyssey), Tony Rice, and Doc Watson. He was already an experienced pro.

Playing the electric bass, which was unusual for the time, was Roger Rasnake, a singer-songwriter from Bristol on the Tennessee-Virginia border.

In 1986 Flying Fish released this band’s first album, What’s That? (FF 377). Here’s the title cut. The band is augmented to six pieces by Vassar Clements on violin and Bobby Clark on mandolin; both played on the album. What we see and hear first is Ginger’s dynamic emcee work. Doug’s composition shows a banjo picker who knew fiddle music — a melodic “A” section followed by a punching Scruggs-style “B” part.

Rasnake made a point of telling me Roland White had sent his regards.

Roland was an old California friend, whom I’d met in 1964 and gotten to know when he was playing with Monroe. He’d just joined the Nashville Bluegrass Band. It was a pleasant surprise to hear from him.

Roger wanted to buy a copy of my book, so I took him up to the library and he bought one which I autographed. I signed several others during the day, including several that people brought with them.

I rested a bit before heading over to Gardner-Webb’s Lutz-Yelton Convocation Center.

That evening was the Doug Dillard concert in the gym. It was good, with Ginger Boatwright doing the MC work, Lamar Grier’s son David picking some nice lead guitar, and good singing by Roger, Doug, and Ginger.

Rasnake did one of his own songs from their album, “Endless Highway.”

There was a grand finale at the end with picking by Horace and the boys, and also fiddler Pee Wee Davis, whom I heard briefly in the back room for a while. I bought a souvenir photo of the Dillards with Andy Griffith. Home and in bed by 11.

On Sunday morning:

Up and away by 7:30, carried my bags to Tom and Carol’s dorm. We hit the road and drove to Shelby where we went, on Joe’s advice, to the Pancake House, a local place on the strip which was sure to have livermush. We went in and sat at a table and when the menu came I eagerly perused it. Sure enough, at the top of the list on the right-hand side was “Livermush and Eggs.” And, in case I’d missed it, about halfway down the same list was “Eggs and Livermush.” So I ordered that and actually ate some. Very peppery, other than that not much taste and what there was didn’t really excite me. I mixed it with eggs, like one does with grits. Maybe it’ll help my banjo-picking, who knows.

In Chapel Hill I stayed the night with Tom and Carol and had a bit of time to visit friends and relations and buy a box of instant grits at a supermarket. Next day I was back home in Newfoundland, writing up my diary.

The weekend at the Earl Scruggs Celebration brought me face to face with a music culture in which bluegrass nestled. Seeing, hearing and talking with Snuffy, Pappy, Horace, and Dan put me in touch with generations older than mine, what Bartenstein has called “The Pioneers” and “The Builders” of this music. I feel fortunate to have seen, met and heard them all. Just as important for me was hearing new younger performers like Ginger Boatwright, David Grier, and Randy Lucas.

This was my first opportunity see my folk guitar hero, Etta Baker. It came near the start of her late-in-life performance career. In 1989 the North Carolina Arts Council gave her the North Carolina Folk Heritage Award; in 1991 she won an NEA National Heritage Fellowship. Wayne Martin produced her first CD, for Rounder, in 1991. Later she collaborated with Taj Mahal. Meanwhile Music Maker Relief Foundation, an organization “fighting to preserve American musical traditions,” gave her the support she needed to pursue her career as a musician up to her passing at the age of 93.

It was also my first time to see Doug Dillard. If Snuffy and Pappy personified the era when bluegrass emerged from old-time, Dillard’s new band blended the contemporary sounds of an era when classic, progressive, and newgrass elements were shaping and blending the sounds heard as bluegrass thrived in a festival-dominated scene.

Instead of an alpha male lead singer/emcee/rhythm guitarist, he had an alpha female. Replacing the mandolin or fiddle one expected in a band with a banjo was an acoustic lead guitar. Instead of an old “doghouse” upright the bass player had an electric. The lead vocals were shared between male and female. Repertoire ranged from bluegrass classics through old pop and rock favorites to band member compositions. The group was touring widely. State of the art bluegrass, 1987.

So how did all this fit together for me? I recalled the start of my visit when Joe DePriest took Tom, Carol, and me to visit the Shelby graveyard.

He showed us three graves: first that of Thomas Dixon, the local writer whose The Clansmen was turned by D.W. Griffith into The Birth of a Nation. Not far away was the grave of W.J. Cash, author of the immensely influential The Mind of the South. Joe and Tom pondered how the two men would have felt about being buried so close to each other; the image that sticks with me is one of Cash glaring at Dixon.

Joe gave us copies of the Greater Shelby Chamber of Commerce’s glossy full-color brochure, Shelby…it’s home. In it Thomas Dixon is identified as the author “whose novel Birth of a Nation became the first million-dollar movie” thus avoiding the fact that book and movie inspired the racist revival of the KKK. It describes Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist W.J. Cash simply as “author,” not mentioning his progressive stances in print against the Klan and Nazism.

Tom wondered, what if the paths of Cash (who lived in Boiling Springs) and the young Scruggs had crossed at the time? He told us:

Cash … thought that the South had no “Culture” to speak of — what would he have had to say about Scruggs’s contribution?

Joe took us to a third gravesite, that of a local Confederate colonel killed in a Civil War battle; after detailing that part of his life its headstone:

… describes him as a lover of the arts who twice rode by horseback all the way to a far-off northern city (Baltimore? New York?) in order to hear Jenny Lind sing. This tells you where Cash’s mind was when he spoke of Culture.

The Shelby brochure ended its historical section saying “Cleveland County has also produced two North Carolina governors and an ambassador, but our most famous son is country singer Earl Scruggs.”

So much for official culture in 1987!

Gardner-Webb’s decision to honor Earl Scruggs reflected a shifting intellectual landscape. A local musician of humble origins — a mill worker — had taken on new meaning and significance because of his national and international recognition and popular culture success. He deserved honor and celebration in his home. I was glad to help.

I don’t know if there were any further Earl Scruggs Celebrations at Gardner-Webb, but today there’s an Earl Scruggs Center in Shelby, which is planning to hold its inaugural Earl Scruggs Music Festival in September 2022.

(Editor’s note: Read part one of Neil V. Rosenberg’s Bluegrass Memoir on the Earl Scruggs Celebration of 1987 here. Read part two here.)

Neil V. Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, and co-chair of the IBMA Foundation’s Arnold Shultz Fund.

Photo of Neil V. Rosenberg: Terri Thomson Rosenberg