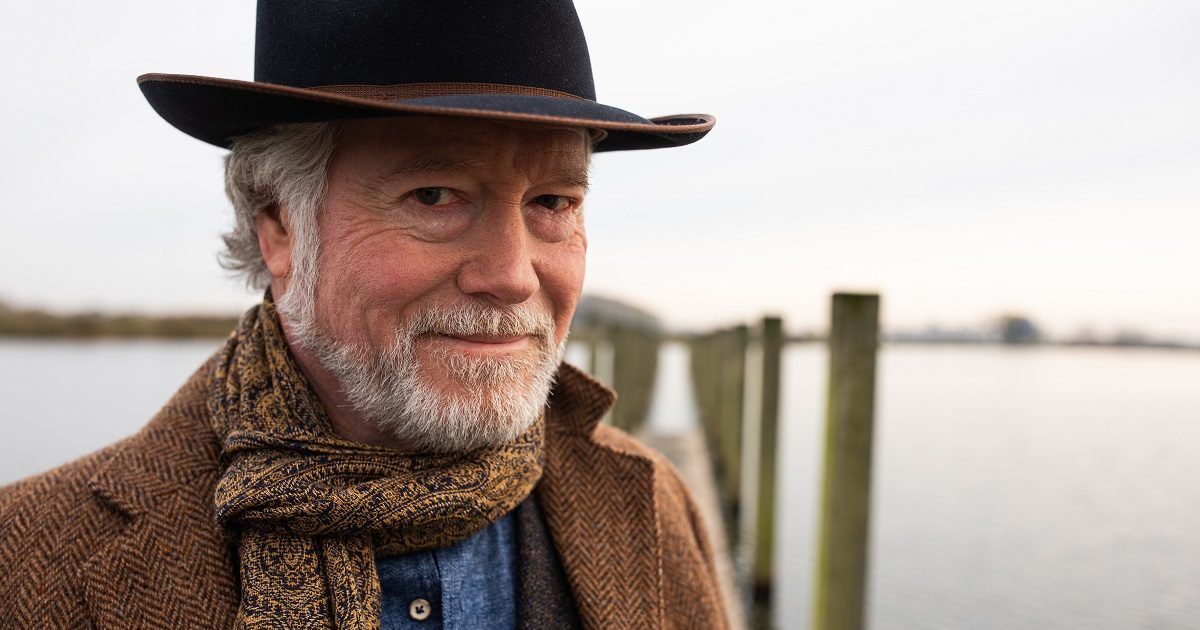

For Arlo McKinley, melody is a secret weapon. He sings about grief, addiction and bad decisions throughout his new album, This Mess We’re In, and the songs stick with you — the rugged emotions and the catchy choruses alike. After listening a few times, there’s a silver lining that emerges, one that provides illumination into his life now.

Now in his early 40s, the Cincinnati musician nurtured his songwriting craft the old-fashioned way, by testing out material to small crowds, absorbing the structure of songs on classic vinyl, and trusting the positive response to his early work even when he wasn’t so sure himself. This Mess We’re In is his second record for Oh Boy Records, the indie label co-founded by John Prine (who was himself a big fan and signed McKinley to the roster).

In this backstage interview with BGS prior to an album kickoff show at Nashville’s Brooklyn Bowl, McKinley also reveals a few of his favorite bluegrass artists and the way the genre has inspired the way he plays guitar.

BGS: You returned to Memphis to make this record, so I’m curious, what was the vibe in the studio this time around?

Arlo: This time, it was different. Die Midwestern [released in 2020] was my first time working with a producer and a studio band. Die Midwestern wasn’t rushed, but we did it in six or seven days. And this time I was down there for two weeks, so it was more comfortable. I had already worked with Matt, and he and I talked during that entire time [between albums]. I had become good friends with Matt and all the guys in the band. This time it was just easy, a lot less stressful. I was much more comfortable, and with the vibe of it all, we got to be a little more creative and really work with each other.

I can hear that comfortable nature and that confidence in the delivery. Did you approach your singing differently on this record than you have on the past records?

Yeah, I think so. I was singing and trying to maybe do things I wouldn’t have always done in the past. One thing about Die Midwestern, we all were coming out of colds, so there’s a lot of that album — a lot of people can’t really hear it, but me personally, I can tell and it always kind of bugged me a little bit. But I love that album. I’ve always been a singer way before I was a songwriter. This one, I just wanted to show vocal ability more. That was important on this album.

How did you get your musical education? Was it a radio station or someone’s collection?

It was a mixture of all that. Music was always in my home, but the church was a big thing. We went to a Baptist church when I was a kid. And that’s the first time I saw that music can bring emotion to people. Because we were in a Baptist church, it’s pretty much three-chord songs with a little bit of harmony. And then my dad had one of the best classic bluegrass vinyl collections and classic country vinyl collections that I have ever seen. And my brothers — I am the youngest of three — had punk rock and metal vinyl, so if my brothers weren’t home, I was in there going through their records. If they’d get home and kick me out, then I’d go to my dad’s room and listen. But someone was always listening to music. I mean, my earliest memories have music in them. My parents would sing, my dad played his acoustic guitar, and you would hear them singing in the hall. It was always around. It came from everywhere. That was kind of what we did as a family.

Were there certain bluegrass albums or bluegrass artists that really grabbed your attention?

Oh, I was always a Seldom Scene fan. And then The Country Gentlemen, my dad would always listen to that stuff. And then a little later, Doyle Lawson and the singer for IIIrd Time Out — Russell Moore. He is one of my favorite singers of all time. I’m nothing like bluegrass, really, at all, but that voice was always there. And then Larry Sparks was also a big one. We cover “John Deere Tractor” quite often. So yeah, I love that stuff so much. It was a big, big part.

Did any of that shape the way you play guitar?

I think it showed me to just keep it simple, for me, because I can’t play like that. [Laughs] It taught me that I’m just a rhythm guitar player. I can’t get my head to tell my hand to move like that. It’s amazing, that kind of playing, and it definitely shaped what I like to do vocally with harmonies. I like to layer my harmonies a lot on albums, and that comes from a lot of the old bluegrass albums.

As you were finding your own voice over the years, do you remember a point where you started to sound different, or you started to sound like you?

Yeah, I listen to old albums now and I think we were just trying to maybe sound like Bruce Springsteen. Or we were listening to Whiskeytown a lot, so maybe we were trying to sound like Ryan Adams. But it wouldn’t have been until writing these songs, probably in 2010, that I really found my voice as a front man singer as well. Because I was always a harmony singer. That was always my thing. This is all relatively new and it’s all kind of gone in crazy directions.

What were some of the jobs you held as you were developing this music career?

I worked for probably over 10 years all together, off and on, for a tuxedo store. We were delivery drivers that would take them to the stores. Then the company got bought out in Cincinnati and the headquarters moved to Michigan, up by Detroit. So, they needed someone to go up there three to four times a week, overnight. I literally would drive in to work and pick up a van that had dirty tuxedos in it. I’d drive up past Detroit, get out, get another van that had clean ones, then bring those back down that day. Then the other drivers would come and take them to stores. I would have 14- or 15-hour nights of just driving. I did that for the longest time. That’s where a lot of the songs for the first album [2014’s Arlo McKinley & the Lonesome Sound] came from. Just from those ideas in my head and listening to a lot of different music. It was a good job, and that’s the last job that I ever had. Then I quit and said I was going to try to go all in.

It worked! What has surprised you the most about the career you have now?

There’s nothing about it that doesn’t surprise me. It comes off the wrong way, I think, when I say it, but there’s never anything else I wanted to do. In a way I think I knew that I could do something in music if I applied myself to it, and really tried to do it. I think that kind of went away for a minute because I wasn’t very confident in my songwriting, but I was a good singer. I still wanted to sing. Then after that Lonesome Sound album that people really were responding to, I thought, well, maybe my songs aren’t so generic, lyrically. I mean, I thought the straightforwardness of it maybe wouldn’t be appealing to a lot of people and I was very wrong. But yeah, I don’t know, it all still surprises me. All of it, in some ways. But then in other ways I think I knew that something could happen if I worked hard at it.

Where did you get your work ethic from, do you think?

For music stuff, it just came from watching other bands, and always going to shows and seeing who was sticking around and who was still doing it. At first you have to face the hard truth of, “Is it good? Is what I’m doing good?” A lot of people won’t accept that sometimes. But if you’re doing something, and you know it’s good, and you’re willing to do the work for it, I think that’s what it was. I saw bands that were really good. And then come 2013, 2016, I started playing with Tyler Childers a lot. And me and John R. Miller, a lot of us, would be on shows in front of 10 people. And watching him do what he did as well. Watching other musicians do their thing is what put that in me.

This new record’s out on vinyl, too. Have you listened to this record on vinyl yourself?

Yeah. I got one spin in right before I came here. I had to end up snagging one out of the box and bringing it home with me, when we first got them. And yeah, it was my first time hearing it on vinyl. It’s everything I wanted. It brings a whole new life to it, really. I’ve been listening to it on my phone. I’ve had it on my computers. I’ve been listening to it through speakers. But to be able to put the needle down and let it go from Side A… It’s just a different thing. I am almost more proud of it now. I didn’t think that was possible because I already thought I made the record that I wanted, but now I know for sure, after giving it that spin.

Photo Credit: Emma Delevante