From Bill Monroe on down the line, bluegrass has always stayed rooted even while it has reached its branches out to embrace each new generation of players. Fiddler Mark O’Connor knows a thing or two about that history, growing up listening to the greats and, eventually, playing with many of them. He collected a dozen bluegrass basic tunes for anyone wanting to explore the form.

Bill Monroe — “New Muleskinner Blues” (1940)

The virtuoso singer Bill Monroe introduced his new bluegrass sound in 1939 to the Grand Ole Opry with “New Muleskinner Blues.” Jimmie Rodgers also called it his “Blue Yodel No. 8” on his recording of the song 10 years earlier. In an Atlanta recording session in 1940, Bill and his Blue Grass Boys revved the song up with his high tenor voice, a faster tempo, and his trademark hard-driving rhythm. Along with his unusual lead mandolin solos and the bluesy fiddling by Tommy Magness, it set the pace for bluegrass to come. I am proud to say that I got to record with Monroe on one of his signature instrumentals, “Gold Rush” in 1992.

Flatt & Scruggs — “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” (1949 Mercury Single)

Flatt and Scruggs made bluegrass wildly successful, bringing it to the mainstream of television, the movies, and to Carnegie Hall. Lester Flatt had, perhaps, a more accessible country music voice than Monroe did, but it was his instrumental counterpart, Earl Scruggs, who lit the music scene up with the perfected five-string banjo roll he adopted from North Carolina banjo pickers. Forward, backward, and alternating, he was an absolute virtuoso on the banjo. I had the Scruggs book and tried to learn banjo the way he did it, as did thousands of others. A thrilling opportunity for me was to record with Earl on his second instrumental banjo album produced by his son Randy Scruggs.

Osborne Brothers — “Rocky Top” (1956)

When the mandolinist and virtuoso singer Bobby Osborne recorded “Ruby, Are You Mad at Your Man?” featuring his astonishingly clear tenor voice, the bluegrass world had another standard-bearing tenor after Monroe. The brothers soon took “Rocky Top” to being one of the most successful bluegrass songs in history. Not many have the chops to sing “Ruby,” but our own Kate Lee sure can in the O’Connor Band! We recorded it in a loving homage to these greats from the 1950s.

The Stanley Brothers — “Angel Band” (mid-1950s)

My mother had nearly 30 Stanley Brothers albums during my childhood. Like with Mozart, mom thought that listening to the Stanley Brothers on the phonograph was good for her children. And it was. Ralph had the most alluring lonesome tenor voice in bluegrass music, and there is no one really close to him on that account. When the old-time mountain soul singer comes in on each chorus to join his brother Carter, Ralph’s was a lonesome, enchanting beauty. The sacred quartet singing of the Stanleys moved the soul.

Doc Watson with the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band — “Tennessee Stud” (1972)

When I was 11, this is the album that I actually took to bed with me at night. It replaced my stuff animal and security blanket, I loved it so much. I wanted this music more than anything else really, and so did a lot of people as the three-LP set went platinum. Besides the virtuoso performances on it by Vassar Clements and Earl Scruggs, I was transfixed by Doc Watson’s guitar playing and voice. He was a larger-than-life figure on this recording. I joined Doc on the road, along with his son Merle, for a few years in my early 20s on the fiddle and mandolin, and it gave me the mountain groove for a lifetime that I will never forget.

Old & in the Way with Jerry Garcia, David Grisman, Peter Rowan, and Vassar Clements — “Midnight Moonlight” (1973)

The folkies and hippies from the unlikely bluegrass stronghold of California were blowing minds in the ’70s. For the next generation like me, it appealed to my contemporary sensibilities. These rockers navigated the bluegrass byways with their long hair, virtuoso playing chops, and a modern attitude with the old music. While it was hard for Monroe to accept, this generation of bluegrass was among the best thing that happened to his music. It gave bluegrass music its future, and prevented it from becoming a museum piece. I must have played “Midnight Moonlight” on stage with former Monroe sideman Peter Rowan hundreds of times in the ’80s.

J.D. Crowe and the New South with Tony Rice, Ricky Skaggs, and Jerry Douglas — “Ten Degrees” (1975)

At the same time that the California bluegrassers were establishing the genre’s jamband future, Crowe ran his ship tightly with this group of new bluegrass virtuosos out of Kentucky. In much the same way that Monroe rehearsed his boys, the New South vintage 1975 album achieved perfection in bluegrass music for their time. Ricky became a superstar and Jerry became a person for which the dobro could have been renamed. And there was the legend in the making — Tony Rice. He was defining what bluegrass guitar was to become and, at the same time, bringing modern songs and singing into bluegrass repertoire.

David Grisman Quintet with Tony Rice — “E.M.D.” (1976)

When this album came out, it changed my young life and musical direction. I knew what I wanted to be, all of the sudden. Although I loved the old bluegrass, I could not see myself embarking on a career doing it. Tony’s switch to the DGQ from traditional bluegrass gave many of us bluegrass musicians permission to partake in swing and jazz, and that we did. I got to join the David Grisman Quintet just three years after this recording was made, replacing Tony as the lead guitarist and playing Dawg music.

Strength in Numbers — “Slopes” (1989)

Once upon a time, there was this group of bluegrass players that upped the ante from the swing, modern country, and rock explorations of its predecessors, bringing in modern jazz and classical sensibilities to the bluegrass music, successfully, for the first time. No one really knew what to call it or knew what to do with it, at the time. Decades later, the words “seminal” and “iconic” are ascribed to the five Nashville lads who dared to take it another step further.

Mark O’Connor — “Granny White Ridge” (1991)

This is one of my recordings and one of the biggest-selling albums I have released. Receiving two Grammys, this album put Nashville session musicians from the 1980s front and center. For a blistering track, the bluegrass and newgrass cats of Nashville were summoned: I called on Béla Fleck, Sam Bush, Jerry Douglas, Russ Barrenburg, and Mark Schatz who all rose to the occasion and answered bluegrass’s call once again!

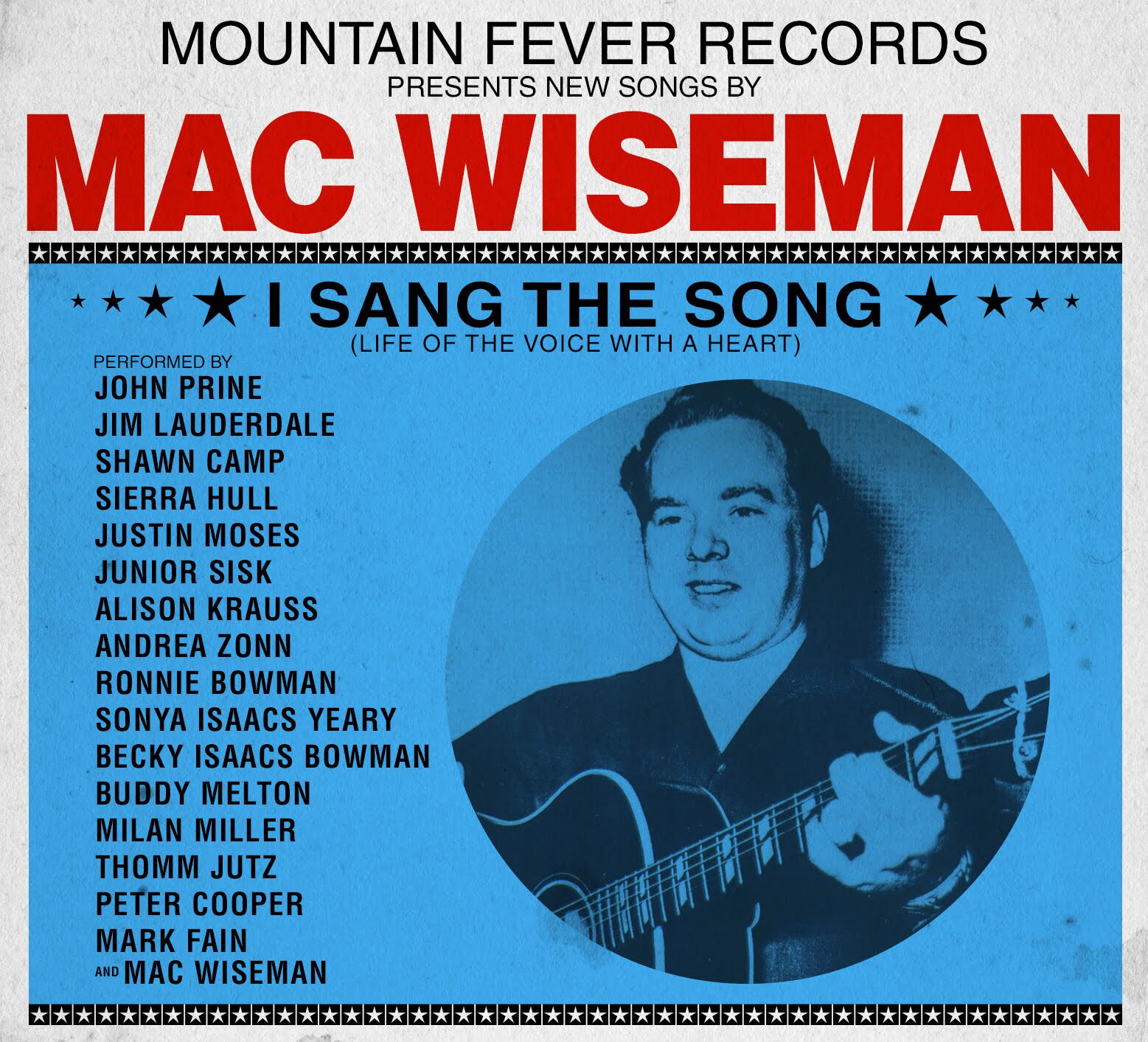

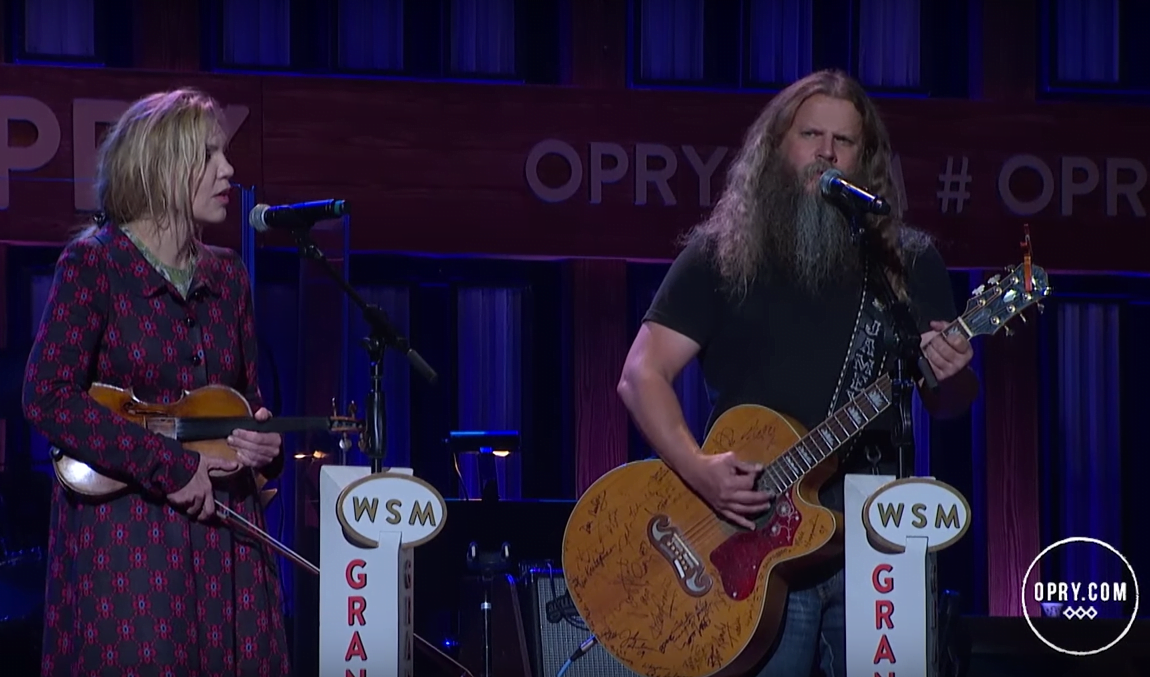

Alison Krauss & Union Station — “Every Time You Say Goodbye” (1992)

Alison made history as the first great female bluegrass star. With the voice of an angel and great bluegrass fiddling to match, she took a page from J.D. Crowe’s seminal bands and made bluegrass about smart, contemporary songs for a new generation of music lovers. Two of my best memories of getting to know Alison are when she beat me in a fiddle contest at age 13 and her parents apologized to me! And when I arranged the old tune “Fishers Hornpipe” for both of us to play fiddles with Yo-Yo Ma. Today we carry that arrangement of the old hornpipe into the O’Connor Band.

Kenny Baker — “Jerusalem Ridge” (1993)

I was like a kid in a candy store when I got to create an album that featured all of my fiddle heroes on it — all 14 of them! But the fun didn’t end there … I got to play fiddle duets with each of them on the album, and recording the very music of theirs that inspired me to play the violin in the first place. The largely out-of-body experience culminated in one of my classic records. For one of the cuts, I got to record with the bluegrass great Kenny Baker on a fiddle tune he wrote with his boss at the time — the Father of Bluegrass, Bill Monroe. Perhaps the greatest bluegrass instrumental tune of all time. We added the tune to the O’Connor Band repertoire as well with our three fiddles in the mix. Always a highlight, it is timeless.