Banjoists Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn are set to the host the International Bluegrass Music Association awards in September. Their presence on stage signals the genre’s expansive growth in recent years, reaching toward the edges in order to better understand the center. It also preempts their second full-length album, Echo in the Valley, due out October 6 on Rounder Records. The follow-up to their 2014 self-titled debut finds the husband-and-wife duo exploring new territory by restricting their creative path: They only used banjos on their latest set of songs, and ensured all recordings could be reproduced live. The resulting conversations they have — a mix of original songs (all co-written for the first time in their career as a duo) and covers of Clarence Ashley and Sarah Ogan Gunning — reveal a quiet muscularity. The limitations, rather than stripping away their imaginative prowess, instead lay fecund ground. If 2017 really is the “Year of the Banjo,” then Béla and Abby are its exciting exemplars, showcasing just how much fun can be had on the edge.

The IBMAs are part of the International Bluegrass Music Association, and will take place in Raleigh, North Carolina, on September 28. Tickets can be purchased through the IBMA website.

As a superstar banjo couple, do you have a conjoined nickname like Brangelina?

Béla Fleck: Abba.

I think that one’s already taken.

Abigail Washburn: I don’t think we create those ourselves. You’re going to have to create them.

Leave it to the people — that’s fair. What does it mean to you both that you’re hosting the IBMAs together?

Béla: I’m quite proud. I’ve had a long association with the IBMAs — from the first year when I won the banjo award, then a couple of years ago I did the keynote. For me, as a long-time bluegrass player and a person in that world, I’ve been a little disassociated, and this means I’m not anymore. I’m right in the center of it.

Abby: And for me, it’s an extreme honor. I’ve played music that’s certainly got a lot of bluegrass elements to it — the old-time Appalachian music that I’ve been playing with Uncle Earl for a long time, and the work that Béla and I do — so just to be so deeply included in the community, but also to be on stage in front of those wonderful people who are preserving and passing along this really bright and beautiful piece of American culture and tradition. I’m excited, too, because Béla and I and the folks that are heading up the awards presentation, are brainstorming lots of ideas to be playful and have fun. We’re excited to get to share the playfulness of our couplehood on stage.

Béla: I think we both look for ways to be creative with any situation that we’re involved in. We’re trying to figure out, “Okay, what could we do that would really be fun and really feel good to everybody?” We’ll see what we come with.

It seems like a crowd that appreciates laughter.

Béla: I think part of that is they’re all together. It’s very safe for bluegrass people. Out in life, we can sometimes feel we’re very unusual and odd, but at IBMA, everyone’s together and so everyone understands these subtle jokes about old-time bluegrass people we all love … or Sam Bush’s hair. I think that’s really special.

I know, like any genre, there are some players who get mired down in tradition and don’t want to see things change, but you’ve both pushed those boundaries in really exciting ways.

Béla: I would just say the very fact that we’ve been invited to do it … because I’ve spent a lot of my life outside of the bluegrass world playing other kinds of music, but I always take bluegrass with me. And Abby, you wouldn’t call her a bluegrass artist at her core, but she’s very associated with it. It’s showing that we’re all part of that family. We’re very respectful of the tradition; we just happen to live on the edge of it. But bluegrass is a very wide musical genre these days. We only lose by chopping off the edges. Even Earl Scruggs was excited about swing. I’m hopeful that this is just part of appreciating the fact that you need some outside blood every once in a while. Where would we be without “Polka on the Banjo”?

That’s what makes for such exciting growth. Well, BGS has dubbed 2017 “The Year of the Banjo” because there are so many projects that are either banjo-focused or banjo-inspired. What would you pin to that explosion?

Béla: I’m a little skeptical of those kinds of things. I think people are doing great work every year and, a lot of times, the great strides come gradually along the whole scope of the curve, but then, every once in a while, there’s a moment when everybody shows up at the same time with new stuff and we do make a big jump. In the past, some pretty wonderful things were happening in the dark that might not even be covered, and might be ignored by the world at large, but now there’s enough interest in the banjo that we can really talk about it and build some energy around it.

Going back to your keynote address from 2014, you mentioned how the banjo was almost a hindrance to your early career because of the way people viewed it. It’s gone through its own sea change in terms of popularity.

Béla: I think part of it is we aged away from Deliverance. It’s an old movie and you have to go find it now. When it came out, it was everywhere and the song “Dueling Banjos” was such a huge hit. It sort of cemented that image of what happened in the movie with how people thought about the banjo, which was an unfortunate piece of that whole phenomenon. I saw very gradually a shift from “Squeal like a pig” to “The banjo? That’s cool.”

Abby: I think there have been a lot of people working really hard for a long time, including yourself. I will compliment my husband, at this point. He’s been working for decades trying to show another side of the banjo to people. Now there are a lot of younger groups who have really taken to it because of Béla.

Béla: Well, a lot of other people, too.

Abby: The list goes on. It’s having an impact. The things that younger people see isn’t Deliverance, but the Bill Keiths and the Rhiannon Giddens, and, gosh, Mumford and Sons. Different kinds of people playing the banjo. There’s the most wonderful representation of banjo that’s come from the edges. It’s very cool.

Very much so. Turning to your forthcoming album, you set out limitations about what instruments you could use and recorded songs that could be recreated exactly on stage. Why set such staunch parameters around creating?

Abby: Limitations are actually extremely freeing, when you set the right ones. We really like being able to create a record that can be experienced live by people. And it’s created these new kinds of challenges for us, because we want to learn and grow and spread our wings as a duo, and working on the eccentricities and complexities to develop the nuance of duo performance means that we incorporated some new ideas into what we’re doing.

Béla: My only addition to what Abby said is that it’s awkward when you make a record that you can’t perform live. We wanted the honesty of the music to be very clear. It’s really very sparse duet music, but we’re finding a way to make it sound as big and powerful as we can with just our two instruments. It’s an art of recording that we aspire to do well at, because I love that part of the process myself. I’m a nerd recording-type guy.

I would say that this latest LP is quieter than your debut and yet it’s no less powerful. I kept thinking of musical conversations that ebb and flow so naturally. Has your playing bolstered other forms of communication between you two?

Béla: I would say we have suffered times on this record because we have a lot of stuff to figure out.

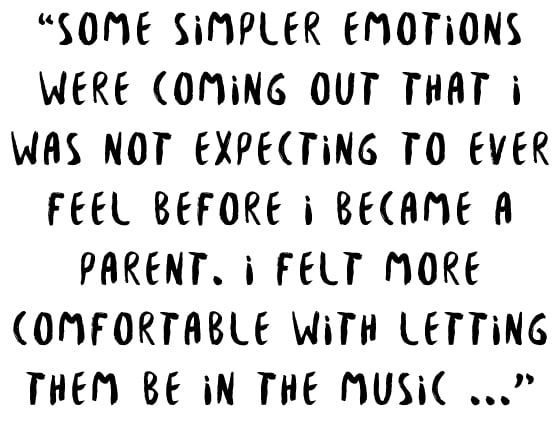

Abby: Suffered times, in terms of the fact that we had an infant. This time, we had higher expectations for ourselves, musically, so we took on new challenges that made for a lot of conflict at times.

Béla: Someone would have an idea, and rather than the other person going, “Yes, that’s perfect,” they’d say, “That’s cool, what if we tried this?” You might get your feelings hurt a little bit, but a little time would go by and we’d come back and go, “Okay, how can this be both of us contributing equally to the song?” I think we’re really good in our relationship at taking each other into account, but in the creative process, things are never exactly equal. You gotta fight for your ideas and then you have to find a way to change them to fit what the other person wants.

Abby: We decided we wanted to write the lyrics together, and that was different from the last record.

Béla: So that was hard for both of us, but we got to a place where we’re both very pleased, and that made our relationship stronger.

Photo credit: Jim McGuire