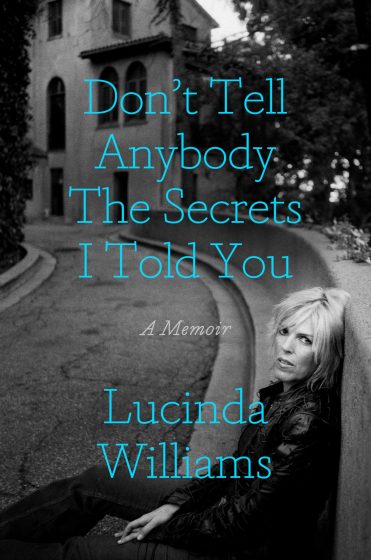

2024 served up a treasure trove of great music books – too many to encapsulate in a concise way. However, it’s still worth a try! So, here is a look at some notable books (in no particular order) that should hold an appeal to the BGS community. This baker’s dozen hopefully provides a diverse and interesting sampling of what has been published over the past year.

There are biographies of superstars like Joni Mitchell and Dolly Parton alongside important if underappreciated figures, such as guitarist Jesse Ed Davis and the Blind Boys of Alabama. Look into the lives of bluegrass icons Tony Rice and John Hartford led by those that knew them while Joan Baez, Lucinda Williams, and Alice Randall each released memoirs that told their life stories in fascinating ways.

There are books here, too, that examine sub-genres like the world of busking and the outlaw country movement, as well as scenes from the musical history of Greenwich Village and the story of a little-known but significant music project that was part of FDR’s New Deal.

There’s a little something for everyone, whether for your holiday shopping list, your winter break stack of books “to be read,” to use up those bookstore gift cards, or for your 2025 resolution to sit down and read more.

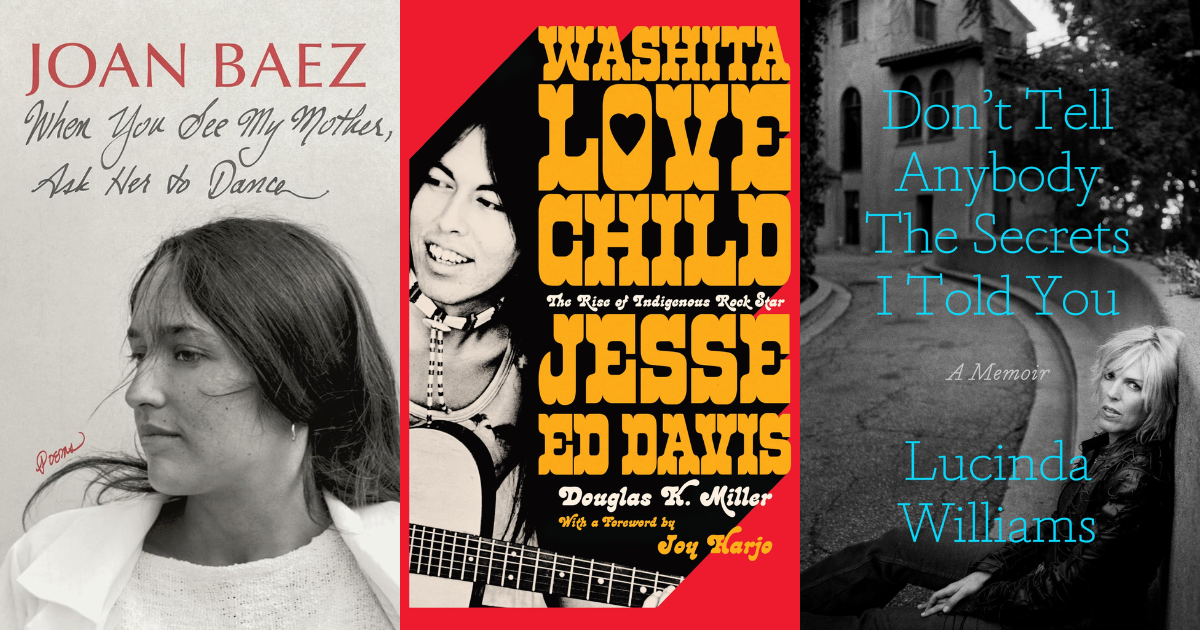

Traveling: On the Path of Joni Mitchell by Ann Powers (Dey Street Books/HarperCollins)

2024 was a big year for Joni Mitchell, with her captivating appearance at the GRAMMY Awards representing another major milestone on her amazing recuperation from her 2015 brain aneurysm. NPR music critic (and occasional BGS contributor) Ann Powers extensively examines the many sides of Joni Mitchell in this stimulating and provocative book. Powers makes it clear from the get-go that she isn’t a biographer and compares her work here to being like a mapmaker. It makes total sense then that Powers entitled the book Traveling. The word not only references Mitchell’s tune “All I Want,” but it also reflects the numerous paths that Mitchell has traveled down during her long, storied career – a journey Powers incisively and insightfully explores over the course of some 400-some pages.

Dolly Parton’s White Limozeen by Steacy Easton (Bloomsbury)

Steacy Easton followed up their Tammy Wynette biography, Why Tammy Matters, by tackling an even larger female country music icon: Dolly Parton. Part of the acclaimed 33 1/3 book series, this compact tome focuses on Parton’s popular 1989 album White Limozeen. Easton views it as a pivotal work for Parton as it represented a triumphant rebound from her roundly disappointing 1987 release, Rainbow. Besides delving into how the Ricky Skaggs-produced White Limozeen found Dolly returning more to her country roots from the more pop-oriented Rainbow, Easton also uses her album as something like a prism to look at Dolly’s wildly successful career and her iconic persona.

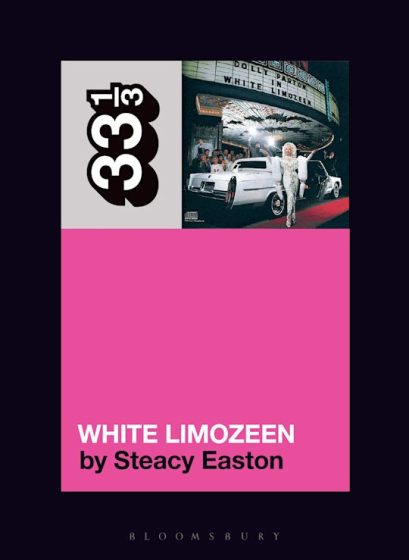

Don’t Tell Anybody the Secrets I Told You: A Memoir by Lucinda Williams (Crown)

Fans of Lucinda Williams’ songs may think they know her through her lyrics, which are often drawn from Lu’s own experiences. Williams’ memoir, however, reveals more about her extraordinary life than even her deeply felt lyrics have expressed. The book is especially strong in covering her quite turbulent childhood involving her father Miller Williams (a poet/professor long in search of tenure) and her mother, Lucille, who suffered from manic depression. Fittingly, Williams prefaces her book by listing the many places where she lived (a dozen before she was 18) which reflects her rootless childhood and set her up for a home in the Americana music pantheon. While the title suggests a racy tell-all, the book feels more like having the great pleasure of listening to Lucinda intimately tell stories from her life – what more could you ask for?

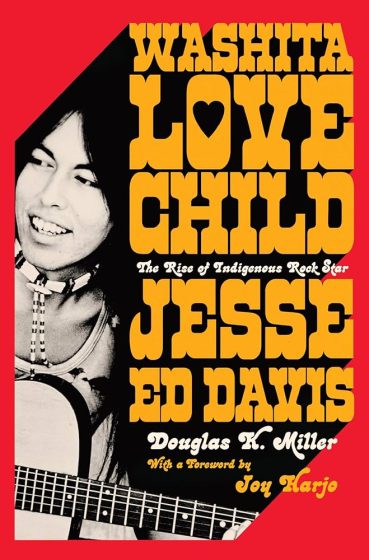

Washita Love Child: The Rise of Indigenous Rock Star Jesse Ed Davis by Douglas K. Miller (Liveright)

Jesse Ed Davis is a name that probably is not familiar to most music fans. Lovers of ’70s rock might recognize his name as a guitarist who worked with the likes of Taj Mahal, Eric Clapton, Neil Diamond, Ringo Starr, John Lennon, and George Harrison (Davis performed at the fabled Concert For Bangladesh). Those who know him from those gigs, however, might not even know that Davis was a rare Native American in the rock ‘n’ roll world. He only really made his Indigenous heritage prominent when he teamed with Native American poet/activist John Trudell during the ’80s in the Graffiti Band. Sadly, Davis’ career was derailed due to alcohol and drug abuse, which also led to his death in 1988 at the age of 48. In this vividly told biography, Douglas K. Miller, a professor of Native American History at Oklahoma State University, turns a spotlight on this ground-breaking and underappreciated musician.

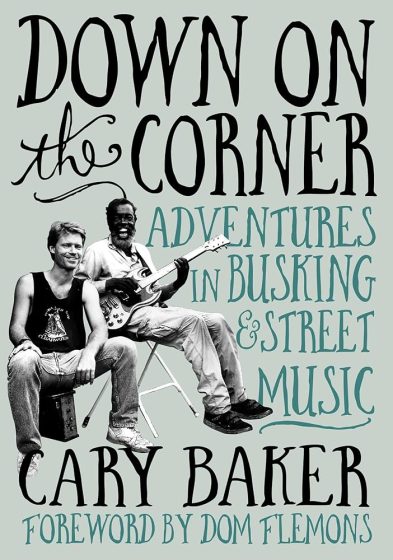

Down On The Corner: Adventures in Busking & Street Music by Cary Baker (Jawbone Press)

For his debut book, longtime publicist and journalist Cary Baker turned to a lifelong music interest of his: street musicians. Early on in this book, he relates the transformative moment when, as a teenager, he was taken by his father to Chicago’s famous Maxwell Street where he saw bluesman Blind Arvella Gray perform on the street. This experience not only led to his first journalism work, but it also launched a love for street music. His enlightening book, which is broadly divided geographically, profiles buskers from across America and Europe. Down On The Corner is populated with colorful characters like Bongo Joe, Tubby Skinny, and Wild Man Fischer along with well-known musicians, such as the Old Crow Medicine Show, Rambling Jack Elliott, Billy Bragg, Fantastic Negrito, and Peter Case, who share tales about playing on the streets.

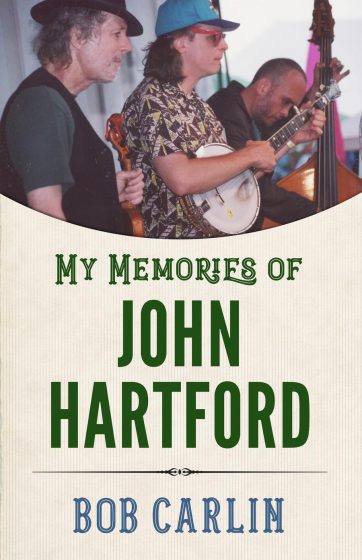

My Memories of John Hartford by Bob Carlin (University Press of Mississippi)

My own memories of John Hartford are of him playing on Glen Campbell’s TV show. He seemed so cool and laidback – and he could play banjo with lightning-fast virtuosity. Happily, Bob Carlin has more interesting memories about the legendary musician, and he comes to this book from a pretty unique perspective. Carlin first met Hartford when he interviewed him in the mid-1980s for the radio program Fresh Air. Carlin (himself an award-winning banjoist) later performed with Hartford and even became his de facto road manager. In his book, he deftly balances his background as a journalist and position as a longtime friend in telling the story of Hartford, who was a true crossover star bluegrass musician of his time.

Discovering Tony Rice by Bill Amatneek (Vineyards Press)

Like Bob Carlin with John Hartford, Bill Amatneek has a privileged perspective when it comes to writing about his subject, the late, great Tony Rice. Amatneek, a musician as well as writer, spent several years playing with Rice in the David Grisman Quintet. Rice was one of the best-ever flatpicking guitarists (and a terrific vocalist) whose career was undercut by illnesses and his own personal demons. Amatneek constructed his book as an oral biography, built around stories told to him by fellow musicians who knew Tony, like Sam Bush, Béla Fleck, Peter Rowan, and Jerry Douglas along with Rice family members, allowing readers to discover the bright and dark sides of this bluegrass master.

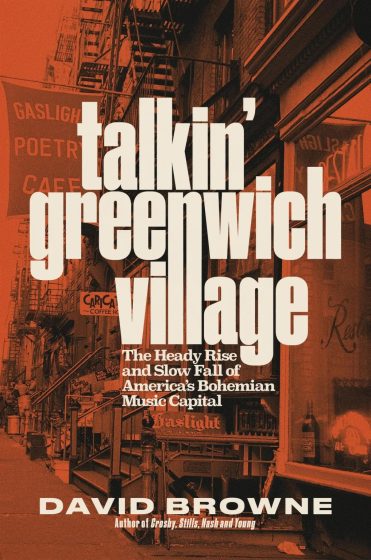

Talkin’ Greenwich Village: The Heady Rise and Slow Fall of America’s Bohemian Music Capital by David Browne (Hachette Books)

As its title plainly states, Talkin’ Greenwich Village discusses the renowned area of New York City that has been a center for bohemian arts culture for decades. The book can be described as a “biography” of both the people (Dave Van Ronk plays a prominent role throughout this story) and the places (particularly the clubs, such as the Bottom Line, Kenny’s Castaways, Gerde’s Folk City, and the Bitter End) that populated the Village’s music scene from 1957-2004. (Browne here basically concentrates on the West Village.) The author of books on the Grateful Dead, CSN&Y, and Sonic Youth, Browne does a masterful job at bringing this neighborhood to life during its many eras. The Village holds a special place in Browne’s heart; he discovered the neighborhood as an undergrad at NYU just as the new folk scene of the early ’80s was brewing. His passion shines through in his storytelling.

My Black Country: A Journey Through Country Music’s Black Past, Present, and Future By Alice Randall (Simon & Schuster)

You may have already heard about Alice Randall and her book right here, on BGS and Good Country. My Black Country has received great acclaim (NPR listed the book among its “Books We Love” for 2024) and justifiably so. An author, professor, and songwriter, Randall tapped all her talents in creating this inspiring work that addresses her life story and investigates the history of Black country music, which she traces back nearly a hundred years to when DeFord Bailey performed on Nashville’s WSM radio station. It should be noted, too, that this isn’t just a Nashville-centered book; it explores Black country music made all across America. Besides enjoying Randall’s literary creation, you can also enjoy her songwriting craft too; Oh Boy Records released an eponymous compilation of Randall-penned tunes interpreted by such artists as Rhiannon Giddens, Allison Russell, Valerie June, and Leyla McCalla. (Of which, Giddens’ performance of “The Ballad of Sally Anne” is nominated for a GRAMMY for Best American Roots Performance.)

Spirit of the Century: Our Own Story by The Blind Boys of Alabama & Preston Lauterbach (Hachette Books)

The Blind Boys of Alabama are a remarkable story. Remarkable in the sense that the vocal group came into existence around 1940 at the Alabama Institute for the Negro Deaf and Blind and made their way out into the world through the gospel music circuit. And it is remarkable, too, that the Blind Boys of Alabama not only remain a group today (they describe themselves as the “longest running group in American music”), but they have earned five GRAMMYs (and a Lifetime Achievement Award) as well as an NEA National Heritage Fellowship. Preston Lauterbach (author of books like Beale Street Dynasty and The Chitlin’ Circuit) has done an eloquent job weaving together stories from band members and other musical colleagues, and turning them into this absorbing biography.

Willie, Waylon and the Boys: the Ultimate Outlaw Country Primer by Brian Fairbanks (Hachette Books)

This book is something of a biographical combo platter. The first nine chapters concentrate on the “Mount Rushmore” of outlaw country: Willie, Waylon, Johnny, and Kris. Those 240 pages are packed with colorful tales of the foursome, whether on their own or together as the Highwaymen. At that point, the book pivots and explores outlaw country’s legacy in the form of the alternative country scene that was burgeoning during the ’90s, as the Highwaymen were ending their run (their third, final, and least successful album came out in 1995). Fans of alt-country and “new outlaw” artists might wish for a deeper dive into this scene. The chapter on “The New Highwaymen” (built upon the idea of guys like Chris Stapleton, Jason Isbell, Ryan Bingham, and Sturgill Simpson as a new outlaw quartet) feels a bit too speculative. Fairbanks, however, is on stronger footing with his “Highwaywomen” chapter, which looks at the actual supergroup collaboration of the Highwomen, featuring Brandi Carlile, Natalie Hemby, Maren Morris, and Amanda Shires that, among other things, countered the male dominance of the original outlaw movement.

A Chance to Harmonize: How FDR’s Hidden Music Unit Sought to Save America from the Great Depression—One Song at a Time By Sheryl Kaskowitz (Pegasus)

This is a book for history buffs who love music – and vice versa. Author Sheryl Kaskowitz (who previously wrote a book on the history of the song “God Bless America”) has dug up the story on a little-known music unit that was part of the New Deal. This U.S. government program led by Charles Seeger (yes, the father of Pete) sent out musician/agents (noted American ethnomusicologist Sidney Robertson was one prime participant) to gather up folk songs around the country. The goal was to use these songs to build community spirit at homestead communities launched by federal government under the auspices of the Resettlement Administration. The projects were considered radical and controversial back then and, consequently, were very short-lived. Fortunately, however, more than 800 songs were recorded and have been stored away in the Library of Congress.

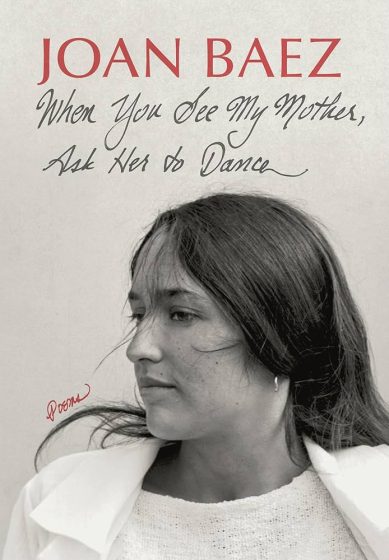

When You See My Mother, Ask Her to Dance by Joan Baez (David R. Godine)

Joan Baez spent over 60 years making music and touring. While she has basically retired from music, Baez hasn’t put an end to expressing her creativity. In 2023, she released a book of drawings and in 2024, she published this book of poetry. There are at least a couple of notable aspects to this poetry project. Baez has long been known more for being an interpreter of songs rather than a songwriter, so it is intriguing to see more of her writer side expressed in this collection. Also, she has struggled with dissociative identity disorder (AKA multiple personality disorder, a topic addressed in the powerful documentary Joan Baez: I Am A Noise). Baez candidly states in the Author’s Notes that some of the poems are “are heavily influenced by, or in effect written by, some of the inner authors,” adding intriguing layers to her creative process – which she displays through the pieces collected in this book.