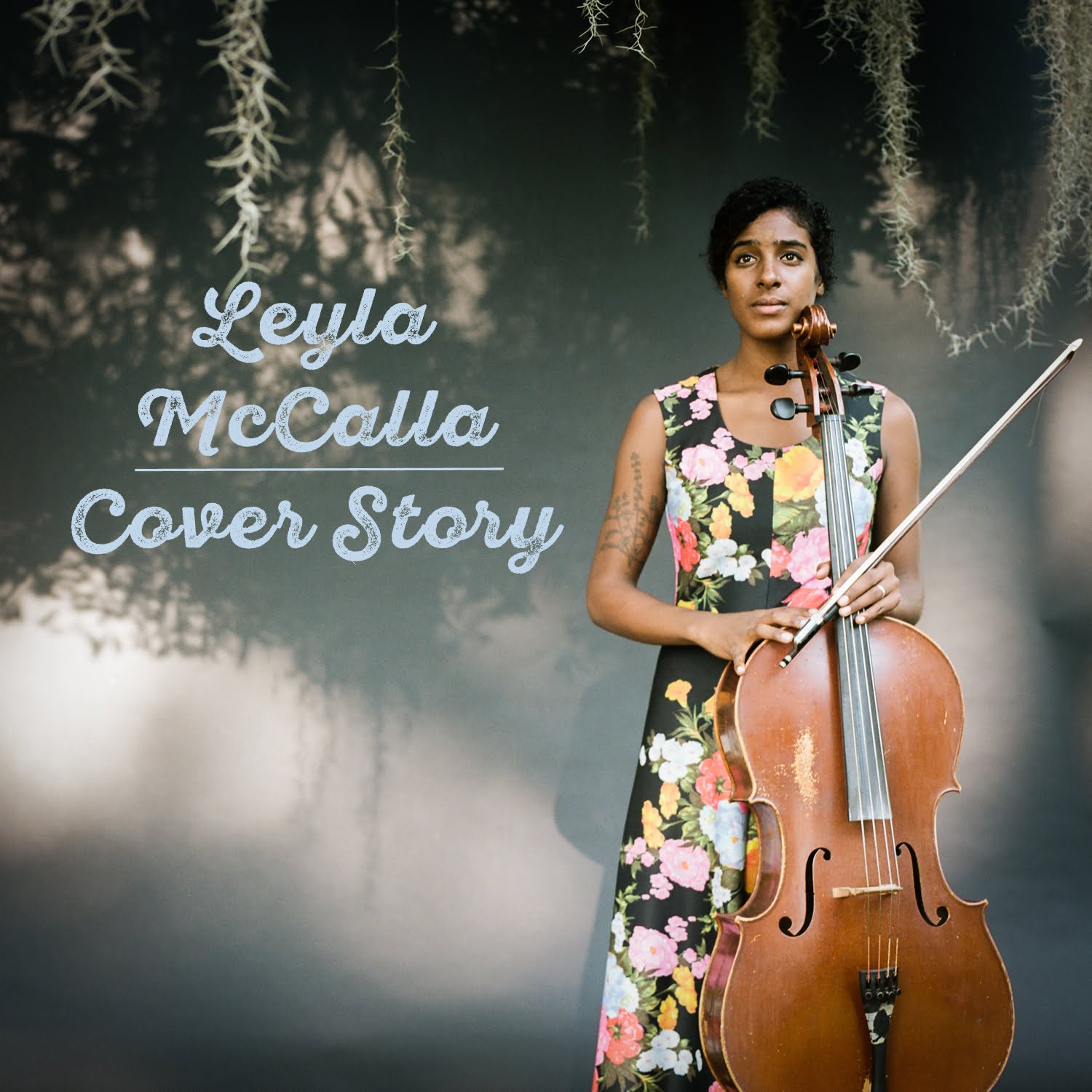

For cellist Leyla McCalla, everything begins with rhythm. On the titular single off her sophomore album — A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey — the formally trained McCalla takes her bow, drawing it back like an arrow and embodying for a moment the song’s noted hunter before releasing it in quick, short bursts that suggest a ballooning urgency. McCalla’s approach twists the cello’s low, luscious timbre to produce a different, but equally physical, effect on the listener. As a composer, her technique defies the traditions that shaped her musical foundation, helping her tell more nuanced stories as a result. The song, based on a Haitian proverb, recounts two narratives almost simultaneously — cello and banjo on the one hand; a second cello and fiddle on the other. Instead of devolving into a cacophony, the stories find their nexus, a point that echoes throughout the album and McCalla’s life.

Both literally and figuratively, McCalla’s music exhibits a web of spatial exchange, particular histories bumping up against one another in ways that reveal their convergences. If her first album, 2013’s Vari-Colored Strings, involved original compositions set to Langston Hughes’ poetry — a dialogue between past and present — her newest work moves beyond that tête-à-tête to exhibit a more polyvocal quality. Not only does McCalla sing in Haitian Creole, French, and English, but she also draws on old folk songs, proverbs, and more to shape A Day for the Hunter, A Day for the Prey. That kind of complexity makes sense coming from a Haitian-American musician who grew up in New Jersey, spent time in Ghana, and settled in New Orleans in 2010. Not finding herself in the traditional American landscape, McCalla unearthed her layered identity through a process of self-discovery that largely came to fruition in the Crescent City. After feeling an unusually tangible connection to the city — one bolstered by discovering many family names in its cemeteries — McCalla began researching Haiti and its connection to Louisiana. As a result, she hit upon the ways in which her identity cannot be confined to one explanation, one story. Her music is the result of those many utterances.

While you primarily play cello, you also play guitar and tenor banjo. How do these timbres embody your identity or your perspective?

The cello has all these different roles it can play, musically, and I think that’s one of the things I really like about it. I tend to play the cello like a rhythm instrument. In a recording situation, I’ll overdub, if I’m using the bow. And even sometimes when I’m using the bow, I’m still playing it like it’s a rhythm instrument. I think I play all of those instruments very rhythmically and, in composing and writing songs, I’m always thinking of those instruments as the ground for the song. It’s a different sort of conceptualization of the music, I think, because I’m not trying to fit into the classical context; it gives me a lot more freedom.

When I first heard [“Day for the Hunter…”], I thought, “Maybe I should play that with a bass drum.” Then I thought, “Well, what if I could experiment with the cello being that sound?” I felt like it was very percussive, so I’m bouncing the bow on the string, and that’s kind of how that song was born. I heard the rhythmic structure for it before completing the lyrics and the melody.

You’ve said before how, growing up, you felt disconnected because you identified as a Haitian-American, but didn’t see that reflected in the United States. How has New Orleans helped ground you by giving you a more physical sense of where you came from and who you are?

I think that’s just it. Being here in New Orleans has given me a very physical sense of place, in terms of my heritage. It’s said very often that New Orleans is the northernmost city in the Caribbean, and I think there’s a lot of truth to that. The more I stay here, the more I see all of these parallels between the culture of New Orleans and the culture of Haiti. Last weekend was Super Sunday and, Saturday night in the neighborhood, the Mardi Gras Indians came out, and we got to watch them parade and battle each other. It was so intense, but it reminded me of the Rara bands. The rhythm is almost the same. It kind of comes from the same place, like spiritually and culturally.

When I moved to New Orleans, I was like, “Huh, what’s going on here?” Some of these things feel so familiar, so I read a lot of books and did a lot of research and I was like, “Wow, how did I not know that there was a mass migration of people from Haiti to Louisiana in the 1700s during the Haitian Revolution? Why wasn’t I told that? Why isn’t that more talked about?” I remember going to St. Louis Cemetery and seeing my family’s names. That kind of tripped me out.

What an interesting way in which your history found you.

Yeah, and beyond that, I feel like myself here. I feel this sense of belonging that I never really felt up north, and I never felt in New York, and I never felt when I was growing up in New Jersey, and not in Ghana when I lived in West Africa. I think there’s something to that. That, in and of itself, is really inspiring to me. I feel so curious about what’s really going on here in terms of the history, but also in terms of how I understand what’s happening in our society and in our culture now. This album is definitely born out of a lot of curiosity and processing of those things.

Speaking of the album, what kind of narrative legacy do you want to leave for your daughter?

It’s a hard question because there are so many things I want to say. I want her to not feel the limitations that so many people feel now. It scares me that she could grow up feeling that, because she’s a woman or because she’s biracial or because she’s Black or whatever. I want her to understand the things that other people have had to live through and I hope that she doesn’t have to live through to have her freedom. I think it’s important to understand; I think it’s important to know the history and have that as a reference for things that are happening in our society today. I think it’s idealistic to think she won’t experience the pain of prejudice of racism or misogyny in her lifetime. I think that would be naïve, but I hope she’s more prepared than I was to face those things and to know how to deal with them.

I would imagine it kind of unfolds as she gets older, too.

Yeah, I think you have certain experiences in your life that are bigger teachers than any book that you can read or anything that anyone can tell you. That will really be part of her learning process is her life experiences.

Do you see your music providing her with a bit of that legwork? As if you’re able to say through your albums, “Here’s where we are and who we are and where we came from. I hope this helps inform you in some way.”

Definitely. Working on this album, as a new mother, that was so close to my heart and on my mind throughout the whole process, since she was physically not far from me, because I was still nursing. There are a lot of songs that were addressed specifically to a mother or to a child that came up on the record, because I feel like the challenge of figuring out survival in our world, it starts really early — it starts with your relationship with your parents. That comes up for me a lot, in thinking about this record. The thing about these songs is that, yeah, this is something I can share with her and talk about.

What a neat conversation piece around the dinner table.

That’s the fun thing about making a record. This is going to last past my existence and past her existence, and hopefully it’s something she can pass on to her kids, if she decides to have kids. Even if it sucks, I would love to hear the music that my grandmother made. The music industry can make you feel like, “Oh God, what am I doing with my life?” But the creative side of it is really magical and gratifying, and will exist for a while.

What have you learned between your debut and sophomore albums?

Oh, man. I learned a lot. I think when you release an album, you tour it when you’re pregnant, and then get married, and have a baby, and then record another album, it’s impossible not to feel like, “Oh God, I’m learning too much!”

Did you have time to stop and take it all in?

I think it’s hard. I’ve had time to stop physically, but mentally, it’s hard to stop and take it in, and especially me. I’m always, “What’s next? What’s next?” We travel so much with my daughter on the road, and my husband and I started playing music together, so there’s a big learning curve there. I feel lucky to work with the people that I’m working with, and I feel I learn a lot from the musicians that I work with about music, about respect, about self-respect, about how to take care of yourself, about how to stay diligent in your work, which I think is a true challenge as a parent. Your time is just not the same anymore.

Well, it’s a consideration and a responsibility of someone else’s time.

Right. I feel I’m still trying to learn what opportunities to be okay passing on, and what opportunities to take. Luckily, I have a team of people around me that I can trust, that I can express myself with and truly be heard. That’s very important, I think. I feel, in some ways, I’m a lot more organized and engaged than I was before. Now I know more of the questions to ask about how we’re planning things, and how to get this music out into the world in a way that feels that it’s the right way.

And also just how to not be afraid to say, “Hey, I don’t really understand what you’re saying. Can you say that again?” I think — especially as women — we’re not taught to be comfortable with that, because you have the pressure on you to know how to deal with the world, and I think just being engaged and willing to stand up for yourself and say, “Hey, this is making no sense. Explain it to me or fix it” — that’s pretty empowering. I think it’s something that’s come a little bit easier to me since becoming a mother, because I have that instinctiveness, like, “I can’t really bullshit right now. I don’t have the time to be cute and please you right now.”

Right, so “Get to the point and let’s get going.”

Exactly. In some ways, motherhood is very empowering, as difficult as it can be and challenging in all these other ways. I feel I’m less afraid and really realizing that I’m a full-grown woman and this is my time to not try to be cute and hide what I think or what I feel. It’s very valid. I wish I’d known that when I was younger. I guess you have to learn.

You do, but thank goodness you’re learning now instead of 20 years from now.

I know! Think of how many artists … the Darlene Love story comes to mind … you know that film 20 Feet from Stardom, and just her not getting credit for all the creative work she did when she was 16? What gives?

Etta Baker — whose music I love and I’ve learned a bunch of her songs on guitar and gotten into that style of music — didn’t record hardly anything until she was in her 60s, and it was because her husband didn’t want her playing music. God, I can’t imagine. I would be divorced immediately. I guess it wouldn’t happen because my husband plays in my band, but yeah. It’s mind-blowing how far we’ve come in some ways, and how much further we still have to go.

Your last album drew upon Langston Hughes’s work, and your new album incorporates a variety of writing, like folk songs and proverbs. What kind of writing strikes you the most?

I think that I am drawn to those things that speak to me immediately, or the things that kind of make my mind turn over and over again. I felt that way about Hughes’s poetry. I feel that way so much about Haitian music. And I feel that way so much about Louisiana music, and so many other things, as well. Reading the biographies of Nina Simone and Bessie Smith … these women who were true pioneers and really sort of paved the way for me to be onstage — me and so many other artists. Reading about their lives and the decisions that they made, and how many children they had, and how they felt at that time, and what they lived through. Those are the things that really inspire me and motivate me. It’s not limited to Black artists or Black expression, but I feel that’s so much a part of my experience as an American it’s hard for me to not think of those things immediately.

I also read the Loretta Lynn biography. I love reading women musician biographies. Like, “God, how do we do this? How does it happen?” She’s like, “There’s no simple task.” It helps me remember that because, when you’re young and you think, “I’m going to be a musician; I’ll just meet the right people and things will just click into place.” And it’s like, “No, you still have to do that creative and spiritual work that feeds your art and feeds your craft” — like how to stay inspired in the face of having to pay your rent or your mortgage or find a daycare center for your kid, or figure out how to get health insurance. All those things. That’s the great balancing act. How to take care of yourself and your family, and also stay inspired and stay creative, and live your life in this way. That, I feel, is a big question for me, and I’m always answering through my work in some way.

Photo credit: Sarrah Danzinger