In the fall of 2004, it seemed like everybody was getting into Trouble. Even with that major label debut album, Ray LaMontagne managed to keep a low personal profile while maintaining the rigorous pace of a promising new artist. Meanwhile, the title track of Trouble got covered by that season’s winner of American Idol and ended up in an inescapable but kinda cute insurance commercial. Other cuts on the album ended up in films such as The Devil Wears Prada, Prime, and She’s the Man. In addition, Zac Brown Band recorded “Jolene” and Kelly Clarkson often performed “Shelter” in her shows (and recently revived it for Kellyoke.)

Now, LaMontagne is bringing Trouble back around for a 20th anniversary remaster and re-release (which dropped this summer) and North American and European tour dates set for 2026. He’ll be singing every song on the record to commemorate the collection two decades after its release.

“It’ll be interesting to see how my spirit reacts to learning these songs again, to going back and listening to them again in that way, to bring it to people again,” LaMontagne tells BGS. “I’m looking forward to it. And I feel like it’s important to do to mark this moment, because these are the songs that brought people to my music in the first place.

“Listening to it again now after all these years, I’m very proud of my younger self, for having the strength of will amidst all the pressures of the music business at the time, and about my writing and the way I wrote, to make the record that I did, and to leave the songs the way I wrote them and not take any advice.”

What was your day-to-day life like before Trouble was released?

Ray LaMontagne: Well, we lived off the grid. I was already married for six or seven years at that point. My two boys were five and three and we lived on a piece of land I bought in Maine. I had built a small cabin on it and we had a hand-dug well that we used for water. We had an outhouse. It was back-to-the-land living and that was just because I couldn’t stand renting. I wanted to have my own piece of ground. But it was really hand to mouth, and we were broke. And that’s putting it mildly. I mean, we were broke, broke, broke. I was working carpentry, sometimes seven days a week, because I would take anything I could get on the weekends just to get a little extra money, because I constantly was trying to improve the cabin. And I never had a car that ran.

You’d made some independent records before Trouble and I’ve read a couple of accounts of how you got your music in front of Chrysalis Music. How did that actually happen?

Someone heard me at a festival and they gave a disc to a college friend who was in the music business. Then he brought it to his boss. I went out and met with Hollywood Records first. I felt that I was in a room with a bunch of cynical people who made me feel kind of gross. I went back home and that guy called and said, “I think they’re gonna offer you a record deal.” And I said, “I don’t want to do it.” He said, “Are you crazy? What do you mean, you don’t want to do it? They’re gonna give you a record deal!” And I was like, “I didn’t like them. They made me feel gross.” So I went back to being a carpenter again, as I was, and went back to my life.

Then it was close to a year later when that guy called me again and said he had gone to a different company. Now he was with a publisher and that was Chrysalis. He said, “I played your stuff for my boss and he really likes your songs and is interested in you as a songwriter. Would you come out and meet my boss?” I talked to my wife about it and then I said, “Okay, I’ll come out.” I went out and I met his boss and played a couple songs in the office. We talked about songwriting and he said, “We want to help you as a songwriter.”

So, they were looking at you as a songwriter rather than as an artist.

And that’s how I got into the studio to make this record, because I was supposed to go in and make demos. What happened was, Ethan [Johns, who produced Trouble] and I met each other for the first time. We’re very different people and we couldn’t quite read each other. Especially at that time, I was very much a closed book, very much an observer. And he’s a type A personality, big ego, big presence, loves to talk – mostly about himself. And I don’t say that critically, I say it with humor! Anyone who knows Ethan will agree with me!

So anyway, it was this strange thing, but I began to realize as we were starting to record demos or talk about songs, that they didn’t really feel like these songs were finished. They thought they were promising. But I was getting a lot of input coming at me very quickly about, “This song doesn’t have a bridge. This song is just two verses. Is that even a song? This song just has four verses and then it ends. Is that a song?” And it was like that right down the line.

The first demo we recorded was “Hold You in My Arms.” We got to a point in the song where Ethan stopped me and said, “This song is just not finished. It needs a bridge.” He started throwing lyrics at me for this bridge and my shield started to go up. I thought, “These lyrics, first of all, aren’t right…” I was resisting and resisting, and he was getting more frustrated with me. He said, “I’m gonna go make a cup of tea. You write a bridge.” So, he went to make a cup of tea and I wrote an instrumental bridge by the time he got back. I said, “It’s just gonna go into an instrumental bridge and then back into the chorus again.” And he said, “OK. I’ve always been told you gotta do this in the moment. So how many points do you think that’s worth?”

I knew nothing about the way these things happen, but in that moment I knew what was going on and I knew why I was there. From that moment on, I was a brick wall. Nothing was changing. I was changing nothing. I’m recording the songs exactly as I had written them and then I’m going home. If you like them and you want to shop them around, great. If you don’t like them, I’m still going home. It doesn’t matter to me, but I’m not playing this game. So that’s what we did. We recorded this record, which is basically the demos the way I wrote them.

How did the recordings go from demos into becoming the Trouble album?

Six months easily passed and the publisher called me and said, “You know, the songs are just… no one wants to sing the songs. No other artists are gravitating towards the songs, but weirdly, record labels are coming forward because they like your voice and they like what they’re hearing, but they like it delivered by you. It works when you sing it, but it’s not working for any other artist.” And that led to the next step of going back and meeting record labels and talking to people about me as a performer, which was not even on my radar.

So it was a whole other challenge. It was like me against my biggest fear. I was much more interested in being a songwriter at that time. So, that’s how it happened. Slowly, and one step at a time, and one thing led to another, and led to another. But again, that’s why, when I hear these songs at this point in my life, listening to it again for the first time, it really hits me, just where that 28- or 29-year-old guy had that strength of will to know at a gut level that what I was doing had value. Just me being me had some value and I wanted to protect that. And it just makes me very proud of him.

It’s interesting to hear that no other artists wanted to record your songs, because when this record came out, a lot of people were singing these songs. What’s the personal reward for you as a songwriter when someone does take one of these songs from the album and makes it their own?

I really like that. It always makes me happy. I think any songwriter would be happy if even one song gets covered by someone else. You feel lucky if one song you wrote even makes it into people’s lives in some meaningful way. If you’re a songwriter and that happens to you once, you’re grateful. I mean, it’s just the truth of it. It’s like any other art form. It’s not easy, and it either will work or it won’t work, because music is a complex language. … It’s probably the same with painters, with dancers, with writers. You just don’t know if it’s going to connect to people, or if people are going to understand what you’re saying, or if it’s going to speak to them in a real way, speak to their spirit in some way. So I’m very grateful. I’m so glad that there are people in the world, all over the world, who understand my language.

Something that struck me about this record, then and now, is that dynamic in your voice. At what point did you become aware of that range, that you could go loud when it when you needed to?

I don’t really know. I feel like I learned to sing just by doing it. There’s some truth to this, that I really didn’t know how to sing even when I went in to make the record. But I was learning by doing it. I had gotten to a certain point where I knew when I was singing incorrectly because I would be uncomfortable or something would hurt in my throat. And I knew that that wasn’t the right way to do it. At some point, I realized you had to really breathe and sing from your gut.

In 2004, before streaming and social media, how did you find an audience?

It was just live shows. I mean, I toured a lot. A lot. And in the beginning, even being signed, I was still just like anyone. I was in a rental car, just me and my guitar, a box of harmonicas, and getting myself from one gate to the next. Those early shows, again, it’s no different than anyone. It’s two or three people and the next year you go back and there’s 20 people and the next year you go back, there’s a hundred people. When people connect to what you’re doing, they will tell their friends about it, and they’ll bring them the next time you come around. But there’s nothing anyone can do outside of yourself to make that happen. It either works – people connect to what you’re doing, to your performance, to the music, and then they’ll tell their friends – or it doesn’t work. But being signed to a record label doesn’t mean anything. It just means they’re investing and they’re gambling. And if you build a career for yourself, then they win that bet, and if you don’t, then they move on.

I’ve read that you saw Townes Van Zandt play a show in the mid ‘90s and I wondered how much of an influence did he have on your writing and your musical direction for Trouble?

I don’t think he had a real heavy influence. I wouldn’t say that, especially at that time. It was too early. I just remember being really moved by watching him play, for a few different reasons. It’s kind of tragic in some ways. He was right at the end, but I could hear the poetry in the songs. That’s what moved me the most, to hear a song and be so close to somebody, eight feet away from him, and hear “Pancho and Lefty.” That story was completely immersive and took me somewhere else. That was really the most powerful thing I took from that particular night. He transported me. That’s powerful. Music can be really powerful if you’re receptive.

To me, your song “Narrow Escape” feels like a spiritual brother to “Pancho and Lefty.”

Yeah, I’m sure it is. I mean, it’s my take on a story song of this kind. They’re very different stories, but I’m sure that’s my “Pancho and Lefty.”

There’s a reference to “Liula” in that song and I noticed that fictional town shows up again, now, as the name of your own record company. So, are you fully independent these days?

I am, yeah. I still have all my same team around me, but I’m making records on my own and releasing them on my own. That’s a natural progression, too, in the way the music business has changed. It was a very different business when I entered it and at this point, especially for me, there’s no reason to be with a publisher or a record label at all. I left my publisher a long time ago, 10 years ago probably, and the record label followed.

I did want to ask about the illustration on the cover of Trouble. It’s not a picture of you. It’s this beautiful image from Jason Holley. What was it about that image that worked for you?

I just thought it was poetic. I saw the poetry in it. You can take lots of different things from that image, but it’s also just a powerful image. And of course, I have always been reticent to have my photograph taken, or to use my photos anywhere. Which, you know, we all have these things. If you’re comfortable doing it, that’s great. If you’re not comfortable, you should feel you have the right to say no.

Other than seeing you in concert, I don’t know that I really saw your face that much back then, when Trouble was out.

I remember telling my manager, “I want to be like the Lone Ranger. I don’t need to be seen and to be known. Just leave them with the music. And that’s it.” You can imagine how that went over. It was really, really difficult, and there were a lot of frustrated people, I’m sure, at the record label and with management. It frustrated a lot of people because they felt like I missed a lot of opportunities that I could have otherwise had. I knew that at the time as well.

But I’ve always felt like I know who I am. I could say no to a magazine cover back then because I know that that’s going to be a day out of my life where I’m going to be miserable, and it’s going to make me uncomfortable. … I’ve never felt like anyone in the press or who had a camera really cares about you as a person. They’re not sensitive to you, and your well-being doesn’t matter to them. They’re just doing their job. And whatever they capture there, they choose what they want. If you have your head in your hands, if you’re doing this, if you’re looking miserable. That’s power and they’re going to use it.

So, I turned down all of that stuff. You lose that opportunity, but I felt, well, I’ll lose that opportunity, true, but you know what? I’ve got a show tomorrow night, and I’m going to sing my ass off, and people are going to feel it. And if they feel it, they’ll come back next time. That’s what’s important, to build a career that is sustainable. And to do that, you need people to fill the seats. If they don’t come out to see you live, you have no career. That’s all there is to it. So that’s the most important thing. And that was then, and it still is.

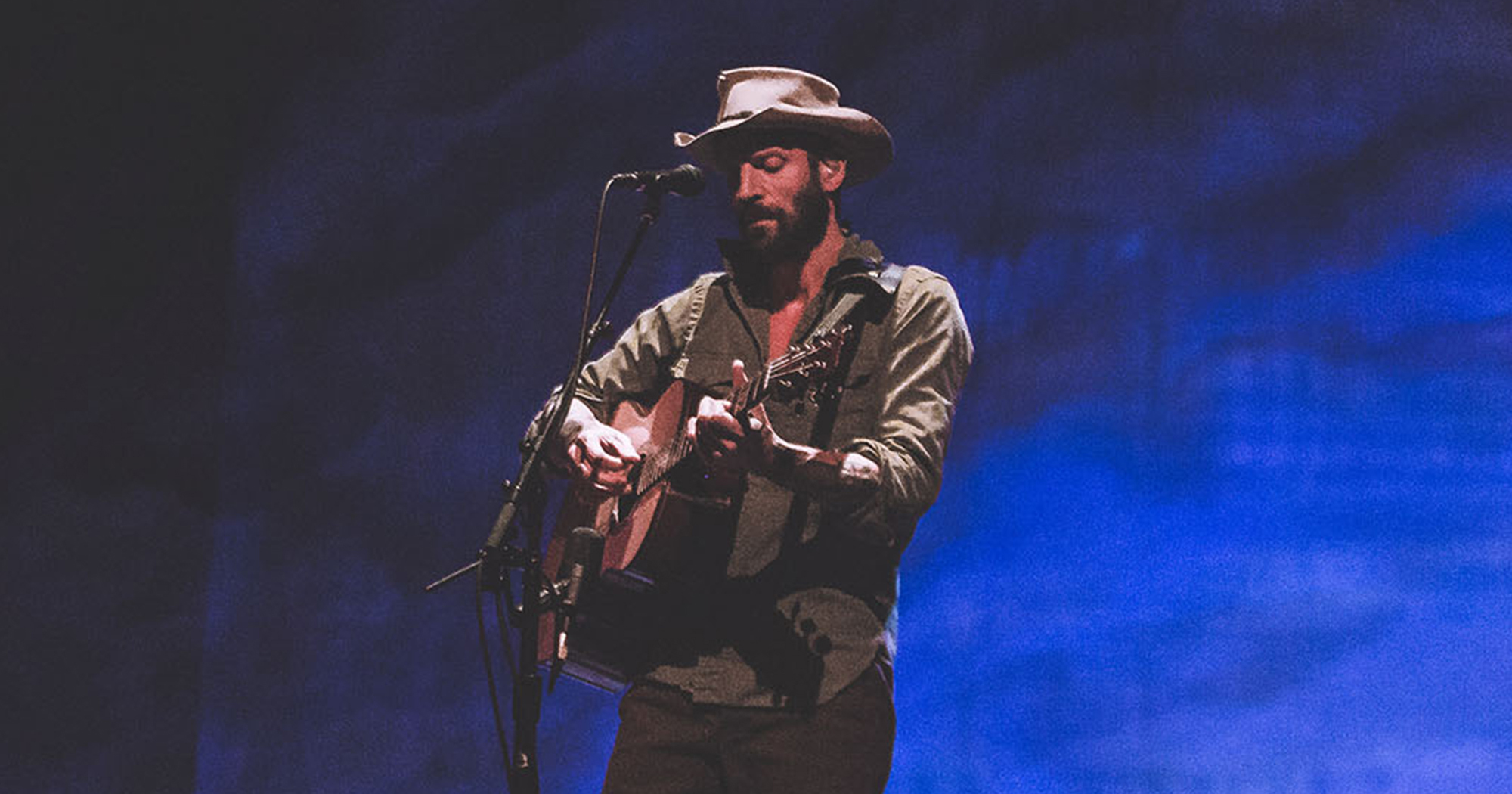

Photo Credit: Brian Stowell