The very first instrument you hear on “New Freedom Blues,” the new single from Town Mountain, is a kick drum. Wait, what?! As the title track of their upcoming album (out on October 26), it’s a mildly, slyly defiant poke at bluegrass tradition (or, more precisely, one interpretation of that tradition) before the full band piles in behind Robert Greer’s gruff, wry lament from a guy who just can’t win for losin’. (Stream the song below.)

Yet as a conversation with banjoist Jesse Langlais makes clear, the members of Town Mountain are more determined than ever to dish up a different take on the bluegrass legacy—one that hearkens back to some of the greatest work by some of the music’s greatest masters during their times of greatest creativity. That should come as no surprise to those who have followed the independent-minded group since they first attracted attention in and around their hometown of Asheville, North Carolina, more than ten years ago.

For while it’s easy to hear the individual progress they’ve made as players, singers and songwriters, and the collective progress they’ve made as an ever more confident and tightly-knit band, their unrestrained energy and freewheeling approach were there right from the start. Whether you’re talking about their shows or about their growing body of recordings, they’ve always had one foot in the honky-tonk and one foot in the jam band world, all the while following the rambunctious roads paved by the King of Bluegrass, Jimmy Martin, as well as his best-known banjo man, J. D. Crowe.

That’s a powerful combination, and it’s taken Town Mountain on a unique journey—one that’s found them as much at home in muddy festival fields filled with energetic dancers as at ground zero for traditional bluegrass, Nashville’s World Famous Station Inn. Still, they’re like almost everyone else when it comes to trying to figure out the 21st century music business, and that’s where our conversation began.

Twenty years ago, it was clear what making a record would do for you as a band: you’d sell it, and hope to get some airplay, so the writers at least would make some royalties. But there was a much bigger economic component to making records back in the day than there is now. So what motivates you guys to make a record?

You’re completely right about the business. I don’t know, it’s just to get that stuff out. The record sales are not what drives the reasoning behind an album for bands at our level anymore; financially, it doesn’t make a lot of sense. The bulk of the material that gets sold is such a small percentage of the music out there. A lot of independent artists are just trying to get people to come to their shows—and one catalyst to do that is to release music. And personally, it’s also gratifying, just to be able to have that tangible object with which you as an artist can say, this is my material.

You guys pretty much write all your own material?

Yes. Phil Barker and I tackle the bulk of the material, Robert contributes a couple of songs here and there, and then we sprinkle a couple of covers in. But yeah, that’s been the premise of the band from the beginning: let’s utilize the songs. And really, for the longest time, songs would come to the chopping block and we would say, well, how bluegrass is this song? And that would be the parameters for how we would choose our material; we succumbed to the ways of the bluegrass world. That was almost dictating the material that we would choose, and all the while, there was all this other material that you’re turning the page on, so it’s just sitting in song notebooks, which we finally realized. So our last album and previous albums are much more of our brand of bluegrass, while I’d say half of the new one is more of a departure from that, but still maintaining the Town Mountain sound.

That’s funny, because it sounds very much like a bluegrass album to me. What are the ways you feel like these songs are less bluegrass than in the past?

There is some bluegrass material on this album, hands down. But if you sit down and analyze the songs musically, you would probably understand a little more of what I’m saying. I would say one thing is that we’ve got a full drum kit in there, which changes the feel immediately. Adding a snare in a bluegrass band totally works, and sometimes you bury it in the mix and can’t even tell it’s there. But with a full kit, it allows some of these tunes to breathe a little bit. We just said, OK, let’s not chop these songs at the chopping block because they don’t fit the mold; let’s move forward with them. And I guess that still maintains some bluegrass integrity, which is good to hear.

It’s not imitative but it reminds me of what the Osborne Brothers were doing, or what J. D. Crowe was doing, in the 1970s—the Starday album, You Can Share My Blanket, the Keith Whitley stuff. And then I notice you hit that low C note on your banjo more than a lot of other banjo players I hear these days, and that’s kind of a throwback thing to Scruggs, J.D., and Sonny. It sort of skips back a generation.

That’s the highest compliment we could be paid. I don’t think anyone could say anything that would make us feel more proud. If you’re getting that vibe of the Osborne Brothers and J.D., that’s totally what we’re going for. Everybody in Town Mountain just loves that ‘70s music so much; My Home Ain’t in the Hall of Fame, anything that Crowe put his stamp on is like the best stuff ever in my opinion, and I know Robert and Phil and the other guys feel the same. Now, I am a huge Osborne Brothers fan; not everyone else in Town Mountain is a huge Osborne Brothers fan, but I am. I’ve personally always loved the mix of hardcore country and the hardcore grass sound—and yeah, collectively Town Mountain is trying to emulate and bring some of that sound back into the scene.

One of the things about the classic bluegrass band creation pattern was that people played in somebody else’s band, went through an apprenticeship, played with people older and more experienced, and then went off to do their own thing. And around the turn of the century, something new started to happen—bands began more like garage rock bands, where people heard the sound of bluegrass and wanted to do it, but they didn’t go through the apprenticeship. How did Town Mountain get started?

None of us grew up in the ranks of the bluegrass community, doing what you’re describing. None of us have. Did we all play in other projects prior to Town Mountain? For sure. But they weren’t products of that hardcore bluegrass environment. Robert and Phil and I were all in bands based out of Asheville, but they were more like pick-up bands—buddies playing music. I’ll say, there’s nothing wrong with what you describe but it does create parameters when everyone’s coming through the same sounds and is being taught how to play the same way—I’m generalizing—and it creates this precedent and guidelines to adhere to, and all the musicians and bands end up kind of getting into that sound. I dig that sound, I get it for sure, and it’s a lifestyle and a way of music and a genre, and totally cool. But developing in that garage rock kind of way allows for a little more outside influence, a little more of a creative approach to the music. And that is how Town Mountain started, for sure.

One of the implications of that is that you have to be more deliberate about learning the older stuff. How’d you guys find your way through the bluegrass canon? How’d you get into that Crowe stuff?

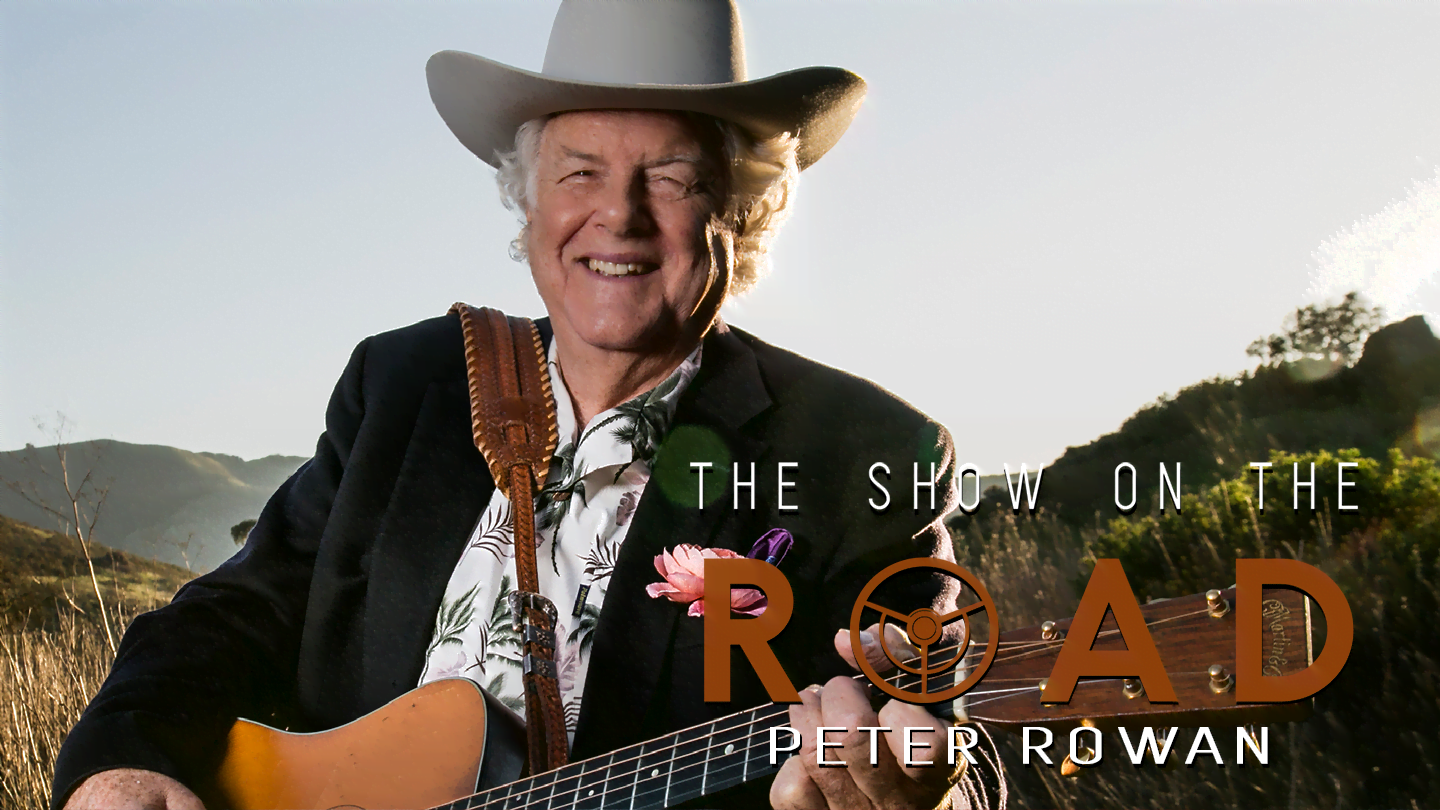

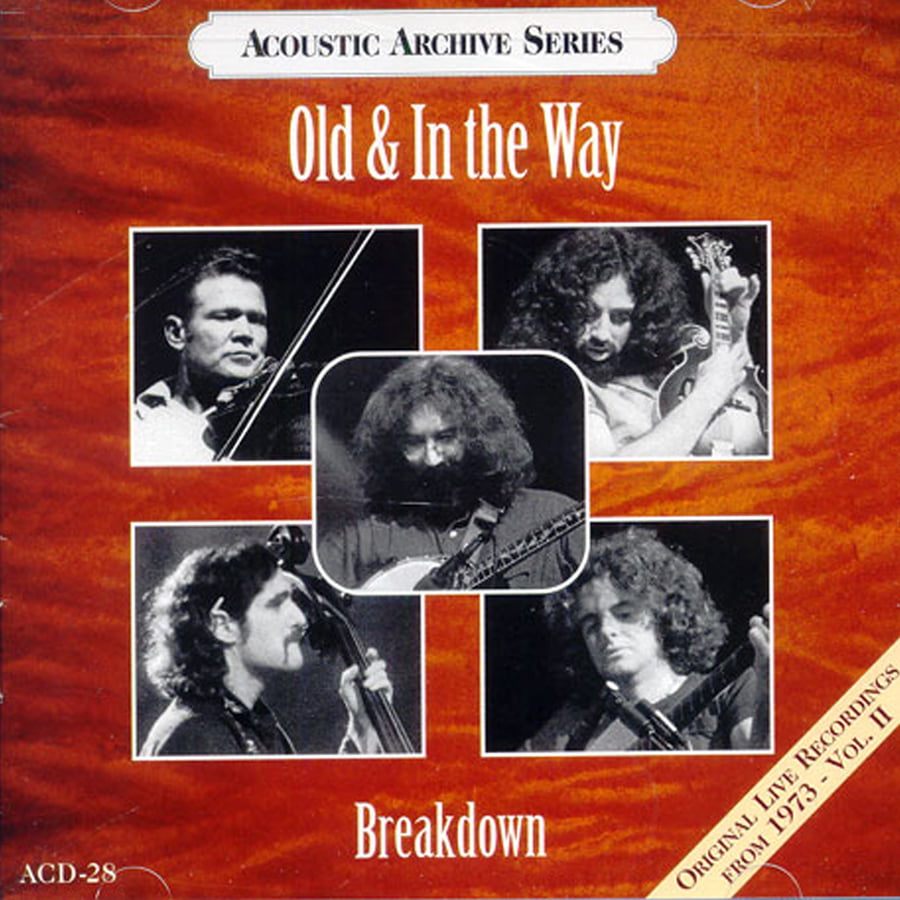

Digging, lots of digging. Personally, my foot was put in the door through Old & In The Way. But as soon as I found out Old & In The Way, I found out who Flatt & Scruggs were, the Stanley Brothers, Jimmy Martin, Jim & Jesse and Bill Monroe. And I found a banjo teacher who would tell me to check out stuff. So then, for five to seven years, the only thing I would listen to was classic bluegrass, or bluegrass in general. I dug in full force. Because at that time in my life I had no idea what it was. I grew up in Maine; it wasn’t part of my life. So I immediately immersed myself in it. And after that period, I could cover so much of the bluegrass canon; I knew by then who J.D. was, and the sound that I love. And then, when I moved to Asheville and met Robert and Phil, it was like, oh, these guys would love Jimmy Martin, too. You know how everybody loves everybody, but this one’s a Monroe guy, this one’s a Stanley guy? We were all Jimmy Martin guys. So our musical taste in bluegrass was very similar from the beginning of the band.

When I look at the band’s recording career, you self-released, then you signed with Pinecastle—that’s a hardcore bluegrass label—and then you made your way kind of back out of the bluegrass mainstream. I look at the variety of material on the album, but right in the middle there’s a very straightforward bluegrass instrumental. I looked at your schedule – you’re playing a lot of clubs and music festivals, but then you’re playing mainstream bluegrass events like Festival of the Bluegrass or Joe Val. Do you feel like you’re in a balanced place between the bluegrass world and all the other stuff?

That’s something we’ve always toiled with, making sure that we’re maintaining a foot in all these different scenes. But we’ve always kind of been a fringe band within the bluegrass world. I don’t think anyone’s ever looked at Town Mountain and said, “There’s traditional bluegrass.” So we’ve always kind of been right where we are right now. We maybe used to do more bluegrass festivals. We made a conscious decision to balance that out with other, all-around, eclectic music festivals. But we hope to get some play on the bluegrass radio stations, and that that will help to keep us in that scene. We certainly want to be part of that music scene as much as it wants us to be part of it.

Photo credit: Sandlin Gaither