We’ve so enjoyed looking back into the BGS archives with you every week for some of our favorite reporting, videos, interviews, and more. If you haven’t yet, follow our #longreadoftheday series on social media [on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram] and as always, we’ll put all of our picks together right here at the end of each week.

Our long reads this week are pioneering, longsuffering, triumphant, innovative, and so much more.

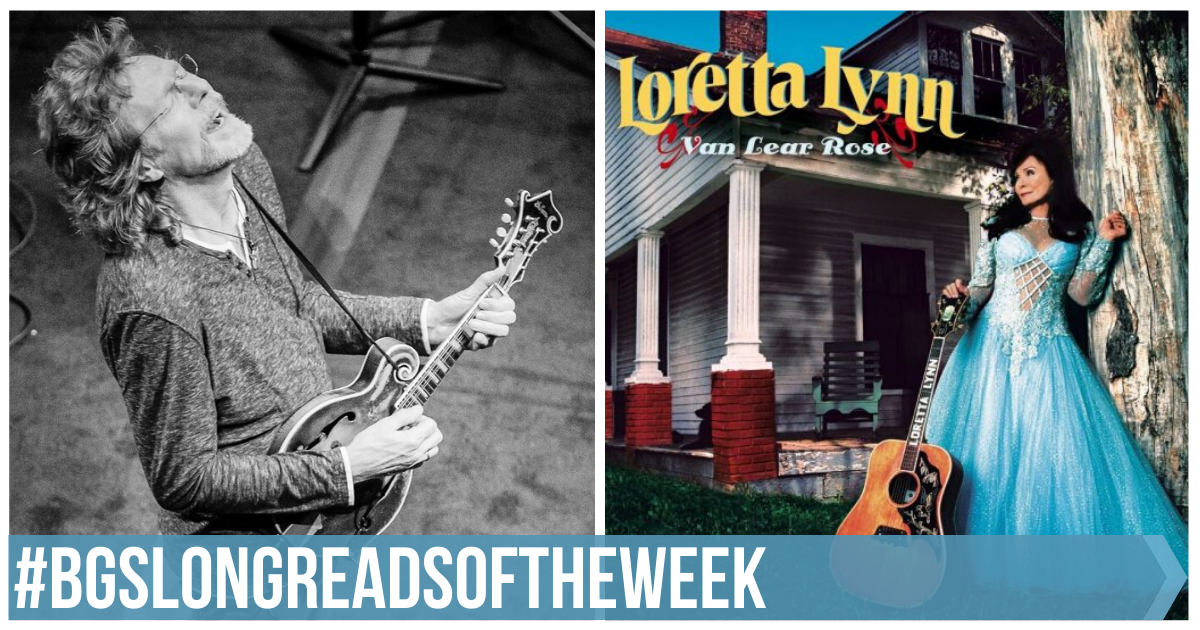

Old, New, Borrowed, and Blue: A Conversation with Sam Bush

April 13 just so happens to be the birthday of this bluegrass pioneer, a man who has had an incredible impact on the genre over the course of his lifelong career. So of course we started off the week in long reads with this 2016 interview with Sam Bush, written by Mipso guitarist and vocalist, Joseph Terrell. Sam talks New Grass Revival, Bluegrass Alliance, the future of mandolin, and so much more. It’s worth a read, birthday or not! Happy Birthday, Sam! [Read more]

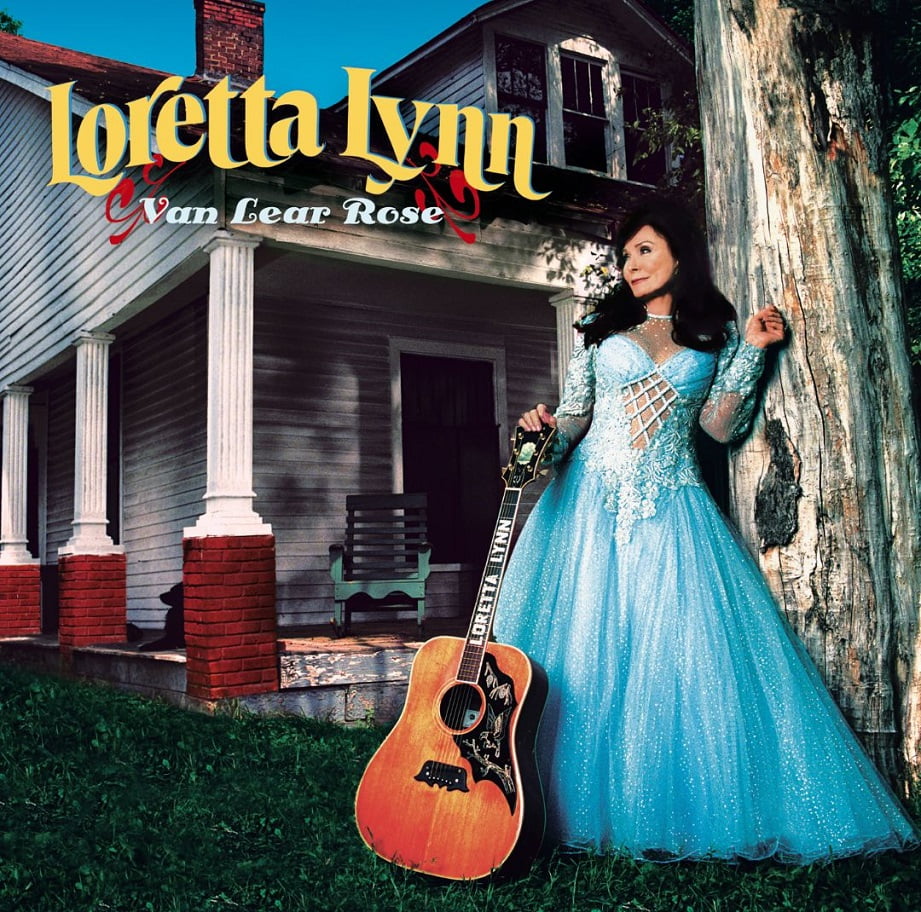

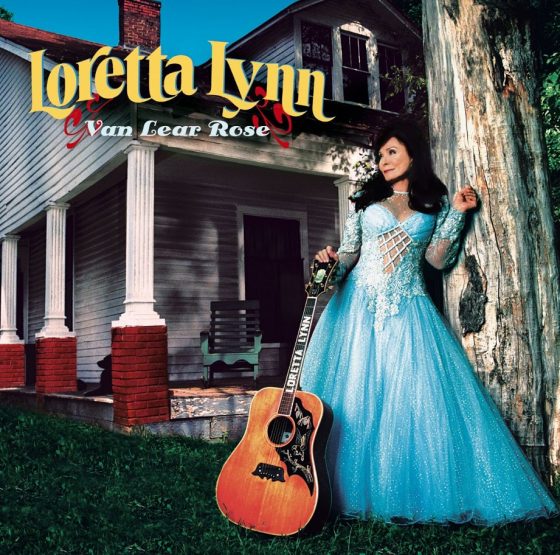

Canon Fodder: Loretta Lynn, Van Lear Rose

It just so happens, we’re featuring two birthday long reads in a row! On Tuesday this week we wished country legend Loretta Lynn a very happy birthday with a revisit to an archived edition of Canon Fodder on Van Lear Rose, her 2004 critically-acclaimed collaborative album made with Jack White. Lynn has changed and innovated upon country music in many more ways than one, and she continues to do so as her career goes on! Just like with Van Lear Rose. [Read more about the album]

Eric Gibson’s Family Shares Autism Story in New Film

We love a two-fer. With this look back into the archives, you get a film choice for tonight or this weekend, too. The Madness & the Mandolin is a documentary following the many challenges and breakthroughs of Kelley Gibson’s (son of The Gibson Brothers’ Eric Gibson) journey and evolution with autism. The film explores methods like exercise, meditation, reading, and music as tools that, combined, can often be the most powerful treatment. We spoke to the project’s producer/director Dr. Sean Ackerman last year.

The Madness & the Mandolin is available to rent on Amazon Prime. [Read the interview]

Like Father, Like Sons: Del McCoury & the Travelin’ McCourys

2019 was a banner year for The Del McCoury Band and The Travelin’ McCourys, Del celebrated his 80th birthday, his Opry anniversary, and DelFest conquered the mid-Atlantic once again. While 2020 is certainly off to a rockier start, the entire bluegrass world — and roots music altogether, too — are so glad to still have this legend of bluegrass making music, laughing a lot, and killing the hair game. At BGS, we’re grateful we got a chance to chat with Del backstage at the Opry last year. [Read more]

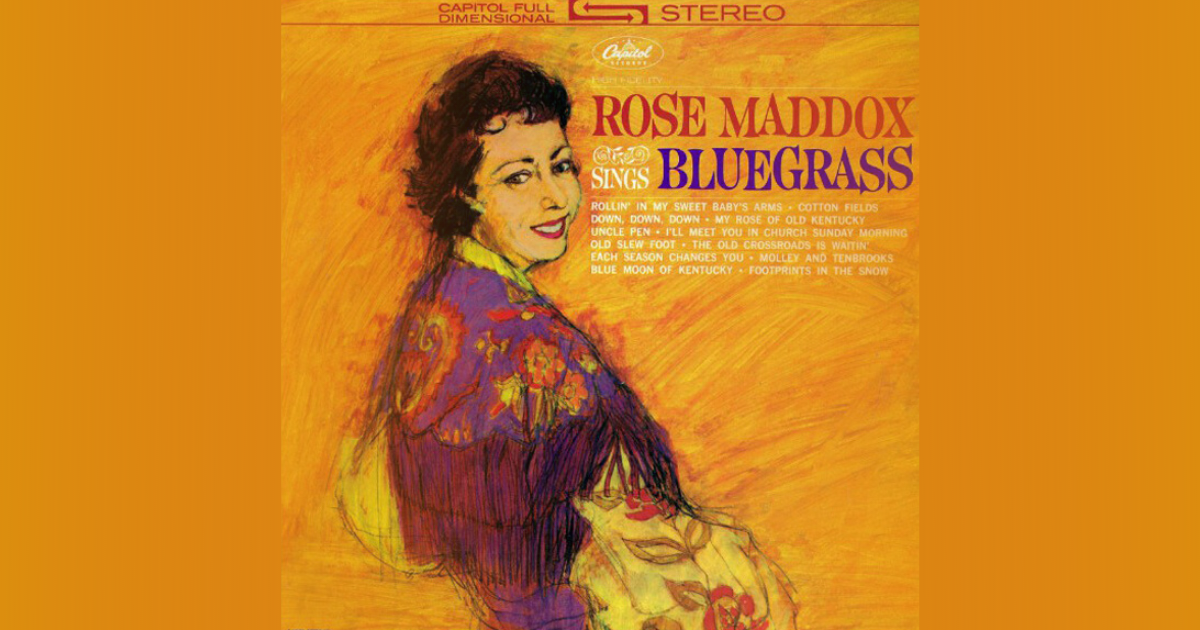

Rose Maddox: The Remarkable Hillbilly Singer Who Made Bluegrass History

She’s not in the Country Music Hall of Fame or the Bluegrass Hall of Fame, and Hollywood has never adapted her story for any sized screen. She’s certainly more than deserving of the former — regarding the latter, you’ll just have to read our feature to see why Rose Maddox deserves to be canonized and then some for her myriad contributions to country, bluegrass, and every other genre in between. [Read about this musical pioneer]