Leyla McCalla couldn’t have known that, weeks after releasing her fourth solo album, Breaking the Thermometer, the New York Times would publish a major report detailing the long history of Haiti’s mistreatment at the hands of France and the United States. But McCalla, the Haitian American daughter of Haitian-born human rights activists and the granddaughter of a radical journalist, was already well aware of Haiti’s troubled past and present. The subject lies at the heart of this album, which grew from a multimedia theatrical project based on Duke University’s Radio Haiti archives.

Radio Haiti was the first Haitian outlet to broadcast news in Kreyòl, the country’s main native language, while challenging government corruption and brutality; the Duke project’s title, Breaking the Thermometer to Hide the Fever, came from a phrase Radio Haiti founder Jean Dominique used to characterize that government’s violent repression of its citizens. Dominique was assassinated in 2000, 10 years before McCalla, a cellist who earned a music degree at New York University, moved to New Orleans to become a “trad jazz” busker. As she learned more about New Orleans and Haitian history, she discovered banjo had played a prominent role in Haitian music. In time, she was recruited to join the Carolina Chocolate Drops — which eventually led to Our Native Daughters, the banjo-playing collective that Rhiannon Giddens formed with McCalla, Amythyst Kiah and Allison Russell. Both groups have focused on reclaiming Black musical history and shining light on Black experiences.

On Breaking the Thermometer, McCalla delves into the Haitian aspect of Black history, weaving spoken memories and snippets of Radio Haiti broadcasts into a gorgeous musical narrative. Through lyrics sung in both English and Kreyòl, she examines Haiti’s political turmoil, rich culture and deep spirituality, while exploring her own identity and relationship to this complex land.

BGS: How did the commission for the project that led to this album come about?

McCalla: I was at a place that I really wanted to be doing something that would be life-changing; that would change the way I saw things and be creatively challenging and fulfilling. So when Duke University asked me if I wanted to be involved in creating a multimedia performance based on the Radio Haiti archives, I said yes. We ended up creating a piece called “Breaking the Thermometer to Hide the Fever” that incorporates video projection, sound design, music and dance. That was definitely way more mediums than I’d ever worked with or coordinated before. It became really clear right away that I would need to have other collaborators, so I hired Kiyoko McCrae to direct. We did a lot of workshopping and brainstorming and creative writing, trying to get to the source of what this was about. It took a few years of working on the project to realize that I even wanted it to be an album.

I found out later that my father had helped Duke University get in touch with Michèle Montas [Dominique’s partner], the journalist who was hugely a part of the making of this record, to help facilitate the transfer of the archive from Haiti to Duke — and that Duke also acquired the archives of the National Coalition for Haitian Rights, which my father ran. In that archive, there’s a picture of me at a protest with my mom. I think I met Michèle Montas when I was 15, at a screening of The Agronomist, the film about Jean Dominique, who is credited with elevating journalism in Haiti. A lot of serendipity and personal connections have been revealed over time.

I take it your parents are very prominent in the Haitian American community.

I can’t go anywhere without someone knowing my parents [laughs], especially Haitian spaces. And everyone is very excited that I’m talking about Haiti, because there’s a lot to talk about; a lot to discover. There’s so much misinformation — or no information — about Haiti.

One of the things that I’ve been grappling with in creating this piece, and why I inserted my own personal story into this — which was not my idea, by the way; it was Kiyoko McCrae, the director, who [noticed] I was getting a lot of memories coming up [while] listening to these recordings and trying to really understand the culture, because I’m [part of] a diaspora, I’m not Haitian — not just Haitian. My identity has a big duality in it, with my Americanism. That became a big point of conversation in all of our brainstorming, and Kiyoko said, “I feel like we’re going to be able to reach people at the emotional level, at the heart level, If you share your perspective.” So that became a storytelling device.

I started to put the timeline of my own life against the timeline that we’re looking at with Haitian history and Radio Haiti, and seeing all these intersections and filling a lot of gaps in my knowledge. Part of the challenge for me in creating this work is that I grew up in a Haitian family that didn’t speak in Kreyòl to me. … We decided to confront that disconnect head on by inserting my story into the narratives.

Americans have this perception of Haiti as a very poor country with terrible dictators, which may be true, but it’s probably very reductionist. What are we missing?

I think we’re missing historical context and significance of Haiti, which is something that is just now starting to be talked about more. Haiti was the first independent Black nation in the Western Hemisphere, and was founded on the abolition of slavery, on the abolition of an economic system that kept Black people in the so-called New World impoverished. Haiti being born out of this struggle to create an identity that was not about being a slave, that was about surviving slavery, is something that is hugely underestimated as a threat to Western power structures.

I think you just nailed something there. That leads to exactly what’s going on in the U.S.

Absolutely. If people understood more about Haitian history and that Haiti’s sovereignty has always been something that it has paid for, in one way or another — that there’s been a lot of meddling in Haitian politics by the French government, by the U.S. government in particular — maybe Haiti wouldn’t seem so far away then.

And yet we love New Orleans because it incorporates and celebrates that culture.

New Orleans wouldn’t be what it is without the Haitian revolution, which started in 1791. There were masses of immigrants from the island of Saint-Domingue — it wasn’t Haiti yet — and masses of émigrés who came trying to resettle their sugar plantations in France, which was Louisiana.

With Haiti, it’s all political, and it’s all about slavery, about these people whose plantations were slashed and burned. The slaves just burned down all the plantations. People were fleeing the revolution and trying to stabilize their wealth. It was French colonists who considered themselves Saint Dominicans, because they had been there for generations. They’re essentially Haitian, but a lot of them were slave owning, and some of them were free people of color. So you see how that moved to New Orleans and Louisiana.

The economy in the United States flourished, but it was obviously based on this barbaric system, where the justification was that Black people are not human, so they can’t have the same rights and privileges that [whites] have. We are still contending with these issues. Haiti needs to be talked about way more, because Haiti is part of really dissecting how the transatlantic slave trade created the economic systems that we’re still living in. … This isn’t just a pure defense of Haiti. It’s aiming for a more nuanced understanding of history, and our relationship to history on a global level.

Most of this album uses the language of the original broadcasts. Were you worried about making it understandable for people?

Well, honestly, a lot of my work has been trying to understand it better for myself. I realized, in the course of the album releasing, “Oh my God, no one knows about this. It just isn’t part of the conversation that we are having.” Ultimately, I want an album that is fun to listen to. I’m passionate about music, but there is an educational component to what I’m doing, because there’s been so much miseducation.

The Caribbean rhythms and texture that you incorporated are so lovely to listen to. Even though you might be telling us about an assassination, it’s done in a way that you can listen to just for the music, or you can listen to the conversations and extrapolate from that.

I developed this music with a man named Damas Louis. He is a Hougan, which is like a wizard of religion, a spiritual leader. He helped me develop the spiritual foundation for the music. A lot of the songs are based in Vodou rhythms. Vodou is another thing that has been so disparaged — especially in the American imagination — dating back to like, the ‘20s in Hollywood, with depictions of zombies. Even in the ‘80s, during the AIDS epidemic, the CDC said that there were the four H’s for contracting AIDS: hemophiliacs, heroin addicts, homosexuals and Haitians. So there’s been a lot of negative stereotypes about Haitians, and their — our — spiritual foundation, which is the Vodou religion. I’m not a religious person, but it felt like such a natural fit to be part of the music. It also felt like it served as a subversive kind of tool for understanding this history.

Are there any specifics songs that you would like to discuss?

Hmm. They all tell different parts that all feel essential to the story that I constructed, but I am glad that you said the music is enjoyable, because it is deeply spiritual and I sometimes felt like, should I even be putting this out there in this way? Do I have the authority to be playing Vodou music?

It’s not like it’s cultural appropriation.

I don’t think so, either. I just have a sensitivity about how Haiti is spoken of and represented. I’ve done a lot of work on myself to just be able to say, “Hey, this is where I’m coming from. And this is the only place I could possibly be coming from, because this is where I am. And this is who I am. This has been my experience.” All of the songs ultimately come from that place.

In “Memory Song,” I just love that line, How much does a memory weigh? What’s the price our bodies will pay? What was the inspiration for that song?

I was feeling the responsibility of representing Haiti well and fulfilling my mission with this work. And then feeling like I wasn’t sure that I had enough to offer, but also feeling like “You are the chosen one; you have been chosen to create this incredible work.” And I’m like, “Oh, God, what if it’s not that incredible?”

But literally, you were chosen!

It makes me laugh to think about now because obviously I take it very seriously, and I was grappling with a lot of my memories of Haiti and trying to figure out how those could be part of this conversation about Radio Haiti. I was just thinking how our memories are so much a part of our existence in our minds and our experience, even with things we can’t [recall]. What is the effect of that on us, physically and spiritually, emotionally?

The lyrics in “Artibonite” really caught me. It’s such a spiritual call and response. Is there some history with that?

That’s a song I found on the archive, originally written by Sanba Zao, who is part of the musical collective Lakou Mizik. Samba in Kreyòl means poet. He’s a deeply spiritual guy, and he was singing in a language — I actually sent the Mp3 to my dad to try to get a translation, but my even my dad didn’t understand what he was saying. I suspect he was singing in ngas, a language with very voodooist lyricism and these old words from Africa; it’s hard to know exactly where they come from. But I love the melody so much. And there was this call and response with these women singers and the melody he was singing, so I decided to write new words to that song because it was honoring the assassination of Jean Dominique, the significance of that, and I thought that was so beautiful.

It stood out not just because it was in English, but because you could feel the spirituality, and it does take you back to how slaves communicated in the fields. And it’s just such a lovely melody. But I loved the determination in your lyrics, too.

He lives in the fields

He lives in the flowers

Hold on to your strength

Hold on to your power.

I was thinking about Jean Dominique’s life; how he was originally an agronomist in the Artibonite region of Haiti, which comprises most of Haiti’s exports. It’s a super beautiful place, and he really had a close relationship with some of the farmers who were trying to unionize in that region, so I kept with that theme. There’s also a proverb in Haiti that says, “Beyond mountains, more mountains,” which is fitting because ayiti is a Taino word that means mountainous land. There’s a bunch of Haitian proverbs that I always try to incorporate into my songwriting; that’s why I was thinking, beyond mountains there are mountains yet to cross, thinking about the cyclical nature of — I mean, this tragedy and all the repression, and how we’re still fighting in these cycles. And once we get over the next mountain, there’s gonna be another mountain, and how much that is just a part of the human experience and a part of life.

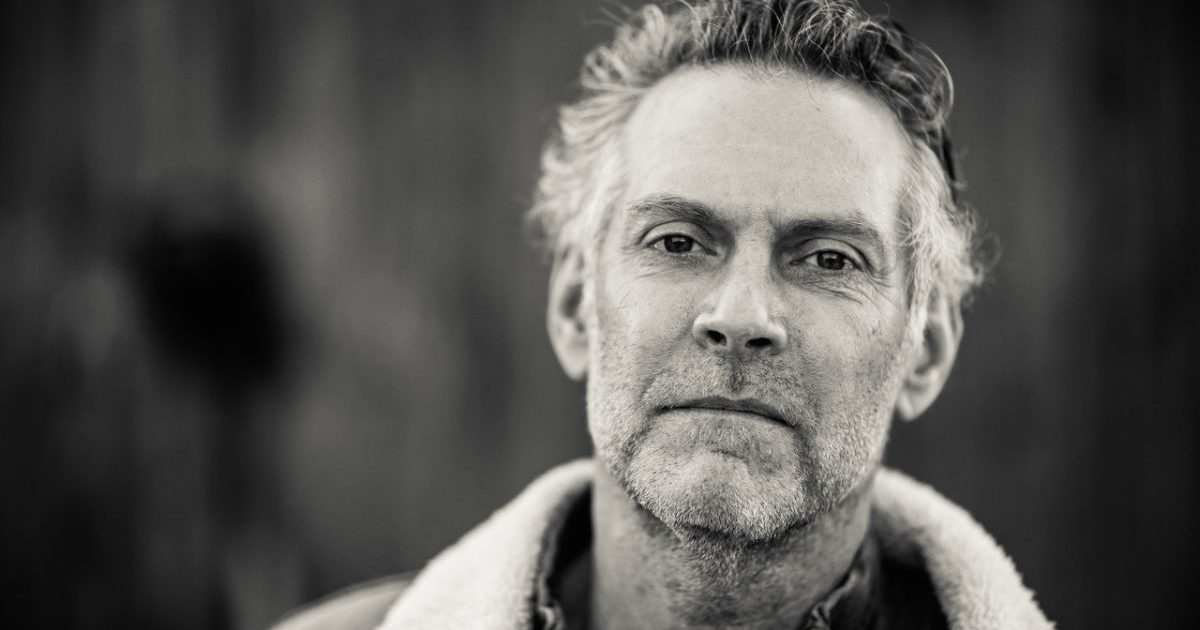

Photo Credit: Noe Cugny