Long before he built a studio in his backyard, long before he twiddled knobs for a range of rootsy artists, long before he developed a reputation as one of Nashville’s most adventure-seeking producers, Neilson Hubbard paid his dues as a struggling singer/songwriter. He got a break more than 20 years ago with the band This Living Hand, which signed in the early 1990s to E Pluribus Unum, the boutique label founded by Counting Crows frontman Adam Duritz. It wasn’t long, however, before the Mississippi native embarked on a solo career, starting with 1997’s The Slide Project (which mined Memphis power-pop bands like Big Star and the Scruffs) and 2000’s Why Men Fail (which channeled shoegazer acts like Galaxie 500). He achieved, arguably, his greatest success with a short-lived project called Strays Don’t Sleep, which he co-founded with Matthew Ryan and had a song featured on One Tree Hill.

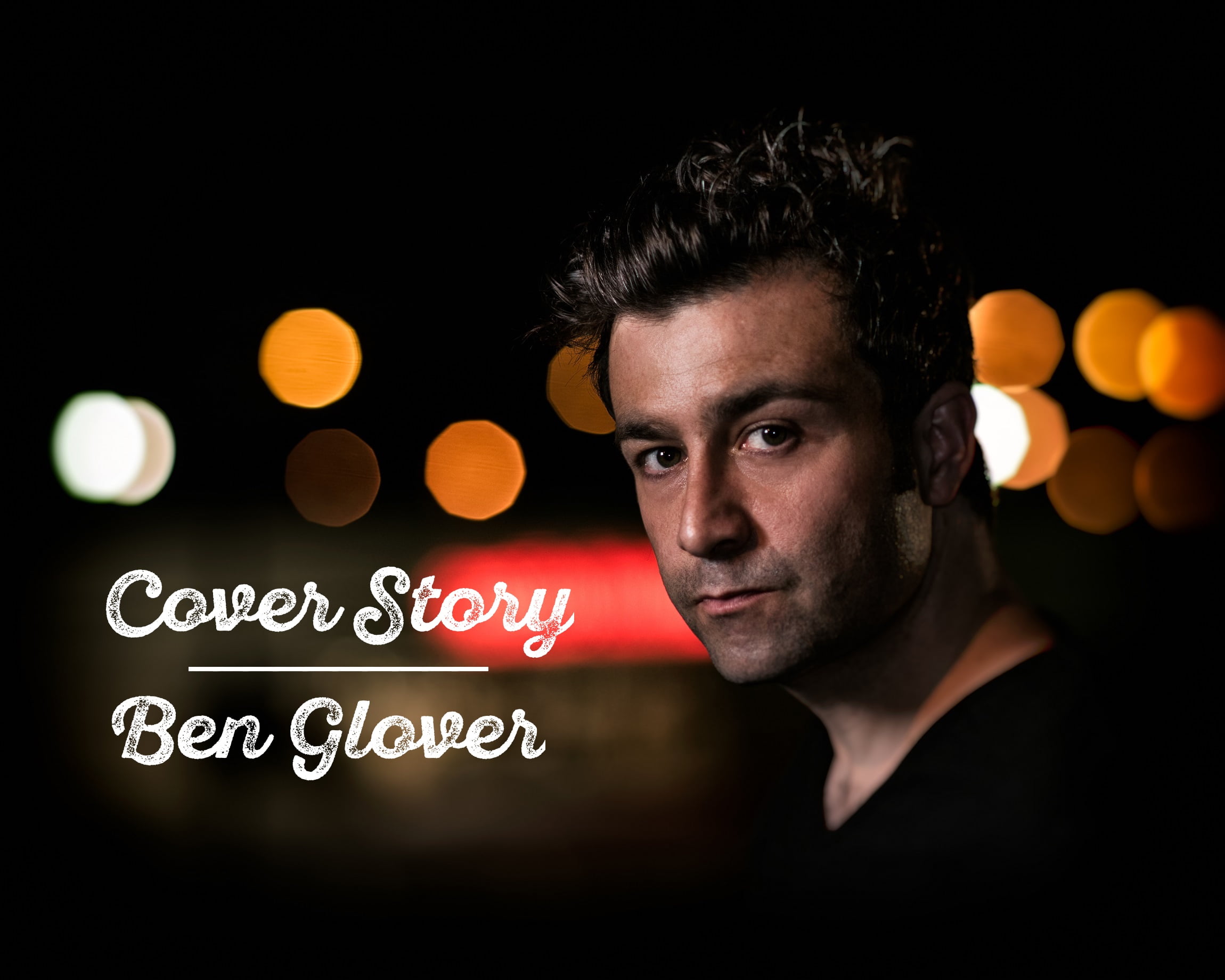

In the 21st century, however, Hubbard has gravitated away from the stage and toward the studio. His résumé is an intergenerational who’s who of folk, rock, and Americana: Glen Phillips’ Mr. Lemons, Apache Relay’s American Nomad, Matthew Perryman Jones’s Throwing Punches in the Dark, Ben Glover's Atlantic, and Amy Speace’s That Kind of Girl, to name just a few. He prefers to remain invisible behind the console, but if he does have a personal aesthetic, it’s one defined by a sense of space and eccentricity, with an emphasis on capturing soulful vocals and juxtaposing loops with live instrumentation.

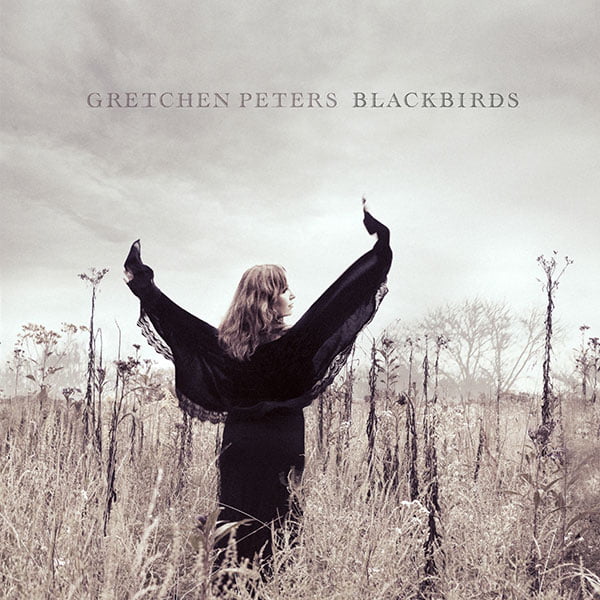

His perspective behind the boards is defined by his experiences behind the microphone and in the tour van. While Hubbard does release solo material from time to time (his latest is 2013’s I’ll Be Your Tugboat), these days he’s more interested in exploring the dynamics of a group. Perhaps his most ambitious project was a country-folk supergroup called the Orphan Brigade, who last year released a period-piece concept album, Soundtrack to a Ghost Story. It’s a novelistic collection of songs set during the Civil War and features an array of singer/songwriters: Ben Glover, Joshua Britt, Jim DeMain, Gretchen Peters, and Kim Richey. They wrote and woodshedded songs for a year, then recorded them in a haunted house in Franklin, Kentucky. It’s artisanal folk — handmade in an industry that favors mass production — and the project not only shows off Hubbard’s imaginative production, but demonstrates how he is rethinking the role of the producer as a creative catalyst.

It’s all about striking a balance between these two sides of the music business: the creative and the technical. “If a couple of years go by and I don’t do something like the Orphan Brigade, I get a little crazy,” he says. “I think right now I’ve got a bunch of different outlets to express myself.”

I knew you first as a singer/songwriter and performer. How did you get into producing?

When I was in This Living Hand with a guy named Clay Jones, we were always doing demo stuff. A lot of times we’d stay up all night at his house in Oxford, Mississippi, and do four-track recordings. He’s an amazing musician, and I always saw him as the producer guy and I was the singer/songwriter. Then, in the late ‘90s, Trent Dabbs — who lives here in Nashville and does the Ten Out of Tenn stuff — asked me to produce his band’s first EP, and I thought, I think I can do that. I realized pretty quickly how much involved beyond just being a musician, but I also realized that I had been doing that all along: just the coordination of making a record and getting from point A to point B. That’s when it really started, with Trent’s record.

Over the last 15 or 20 years, I became an engineer, out of necessity, and I started mixing records. I’ll mix other people’s records that I didn’t produce. I came at it as an artist/writer first and then ended up on the technical side of it. All my favorite producers are that way. They’re artists first. Even somebody like Rick Rubin. I was listening to an interview with him, and he was talking about it from the perspective of just being a fan of music. I think that’s always a good way. If your first instinct is just to twist a knob, then I don’t think that’s good. The only thing that really matters in any of this is what the song is, what the performance is. Does it resonate with people?

How does that inform your process?

I always try to figure out what someone does — what their thing is — and just turn that up as loud as it can possibly be. That’s the most important thing. It’s not about putting my stuff on their record. Sometimes you need to be invisible, just like sometimes you need to add things. But the most important thing is that their thing is the loudest thing. I think it helps to have been a recording artist and have gone through the process so many times myself.

So you’re trying to balance technical ability with songwriting knowledge?

Absolutely. The emotion that the artist is trying to convey … that’s got to be the most important thing. The technical side of it should never get in the way of that. The studio should just be a tool that you use, like a hammer. You shouldn’t be thinking about the hammer when you’re building something. You should be thinking about what the house is going to look like. That’s what I try to do. That’s the mindset I try to stay in when I’m working with people. What is the emotion this artist is trying to convey, or what is the story they’re trying to tell? And how do you get the listener as close to that as possible.

Can you tell me about your studio?

It looks like a little nothing out behind the house, and then you walk in and it looks much bigger on the inside. This is actually the second version of it. I had one, a little barn/garage kind of thing. That’s where we made Glen’s record — a lot of records, actually. The new version is about three or four years old, and I was able to incorporate what I wanted. I built it from the ground up. It still looks like a little garage, but it’s got vaulted ceilings, wood floors, a tracking room, iso rooms — all the things that I’d want out of a studio. But it still feels vibey. It definitely has my feel in there.

I always liked recording in houses. I never liked being in the most professional studios. They made me feel uptight. You’re watching the clock. Even the air in there feels funny to me. I always like to walk into a place where you’d actually want to hang out, where you feel comfortable. That’s a big part of it, too — just making people feel comfortable. That’s the only way you get people to be honest. Or maybe that’s just me. Sometimes people like to … I won’t say manipulate … but sometimes producers think they’re pulling stuff out of the artist. I have always found that great singers can sing, but you have to let them be comfortable enough to sing. So you want them to feel inspired by a place, even if they don’t know it’s happening.

Every artist who comes into the studio is going to be very different in what they do, which makes your approach different. But is there anything that you do that’s the same from one artist to the next?

Probably just hanging out. Getting to know them. That’s the most important thing to me, when I’m starting a record. I don’t want to just say, "Hey, my name’s Neilson. Let’s make a record." To me, you have to understand where they’re coming from and speak the same language. You have to know what they mean when they say something and they have to understand you when you respond. You have to build up some trust, at least if you want to get something good in the end. You don’t want everybody looking at each other going, "What is that thing? What did we just end up with?"

What you’re trying to start with is a roadmap. You’re trying to find the map of where you want to go. But the thing is, you’re going to end up somewhere different every time. That’s just part of it. You can’t know the ending of the story. That’s why getting to know them at the very beginning of the process, just hanging out and building up some trust, is so important. It makes you open to what is going to be revealed at the end of the process. Another thing that I’ve always said — but it’s never going to be possible — it’d be awesome if you could make a record and then burn your studio down. Rebuild it every time. Then you would never be churning out anything the same way.

When I started Glen’s record, he said he wanted to do a more late-night-sounding record — something he had never done. It was all based off mellow, intimate songs, so we started with the vocals and worked around that. I just did a record with Ryan Culwell about a year ago called Flatlands, and he’s gotten a lot of attention lately. We started with the same kind of technique. He was just playing stuff for me. No headphones. Just get in the room and play the songs as many times as you want. We’ll record them all and find the best takes and go from there. Some songs sounded good like that, and some songs we realized needed a band.

It seems like you could do that anywhere — away from the studio, away from the technology that drives most recording.

We’re in this time period when anything is possible. There’s nothing you can’t do. If I wanted, I could make a record with my dog. I could let her bark her head off and, if I got enough barks, I could get the scale. Then I’d get her running around the house and build loops out of the sound of her feet. Actually, that might be cool, if you could do it musically. But if you’re just trying to set up a grid and make it too perfect, then it won’t have much feeling. Building loops and making that kind of music, however, is incredible when it’s done well.

One of my favorite records of all time is the Kanye West album that Jon Brion did, Late Registration. I know everybody has their thing about Kanye, and I’m the same way. Sometimes it’s a little much. Bu the music on that record, everything about it — the beats, his rapping — everything sounds handmade. A lot of original hip hop is like that. Very handmade. I love that stuff. It’s not there to be perfect. It’s just there to have feeling.

Is that something you try to emphasize in your own work — that sense of the hand-crafted?

I think handmade is another word for real or organic. You can make things with loops that feel that way as long as they feel human. I’m working with an artist named Audrey Spillman, who’s also my girlfriend. That’s the first time that’s ever happened, where I’ve dated an artist. She’s this weird mix of indie-pop, soul, and a little bit of jazz. I spent a lot of time making loops for us to play to — just her making sounds with her mouth or things around the house … organic and very interesting sounds, plus some ambient stuff. When we ended up tracking a band with her singing live, we were playing to these loops that we had made. So it wasn’t just a straight-down-the-middle-of-the-road record. I’m mixing it right now. I haven’t gotten to do that kind of record in a while, because I’ve been doing a lot of live-sounding records, like the Orphan Bridge record. We all got together and did it live in a house in Kentucky. It’s different. But that’s the thing. It’s most inspiring to me when a record is dictating your process. The art is dictating the process, not the other way around. That’s when I feel like I’m really doing something cool.

Both of those records sound very different from the new Ben Glover record you did, The Emigrant. It’s very minimal, with voice and guitar and maybe a few ambient elements.

That’s probably the fifth record we’ve worked on together. The first couple were more straight-ahead Americana records, very singer/songwriter. The last one we did (Atlantic), we went to Ireland and recorded in the house he grew up in, with the band sitting in a circle in the living room. For The Emigrant, he knew he wanted to do something that would explore his Irish roots. So we started with that.

We recorded his acoustic differently from how I’d ever recorded, but I thought it would work well for what he was trying to do. It took up a different space. We needed the guitar to function in a certain way, so I’d mic it this way. We knew we weren’t going to put a lot of instruments on it. Everything was going to be super important, because every element was going to take up a lot of space. And the vocals have to be arresting. Of course, the vocals always have to be arresting. That’s the most important thing on any record. But they had to stand out on this record. It’s funny — the record we did in Ireland was about his connection to the Mississippi Delta, and then he came back here and we made a record about missing his home in Ireland. He felt caught between two worlds, always going back and forth and feeling like an immigrant in his own country. That was the start of the new record.

It seems like place is very important to you. It almost sounds like it determines the creative process.

I’m always up for going somewhere new and pushing myself to a place where I’m not sure what the end will be. That’s inspiring because it makes me more creative. I know the drum sounds I can get in my room here, and I’m always manipulating that. But there’s just something really inspiring about being somewhere you’ve never been and making music there. It’s probably the same thing a performer feels when he gets on a new stage in a city he’s never played before. The reverb might sound different, or the crowd reacts differently, or whatever. It’s a human thing, and I’m always trying to tap into that. There’s so much calculation in the world right now. But I think spontaneity is part of true art.

I do a lot of film stuff, as well, with a guy named Joshua Britt, who’s also in the Orphan Brigade. Just some music videos but also some music documentaries to chronicle the records we do. We’re about to do a record with him and me and Audrey and Jim DeMain and this artist from Scotland, Dean Owens. It’s called Buffalo Blood. Dean has gone out West a lot and is drawn to Native American stories, and he started writing a lot of songs about that. He got to know Josh and Audrey when we were making the Orphan Brigade record, and we started writing together and playing songs together. It was something really cool, but what did we want to do with it?

We had done a documentary about the Orphan Brigade record and we decided to do something similar with this one, so we’re going to talk about why we want to write about Native American history and why that’s important. And we’re going to make the record in the desert — literally outside in the desert — at the end of May. We’ll be flying out to New Mexico, so it ought to be a beautiful setting to make a record. We’ve been dealing with the logistics of how we’re going to do it. I think we’re going to have to have a mobile battery-powered rig. Maybe that’s too much work for one record, but that’s the stuff I want to do. I have no idea how it’s going to sound. I just know I can’t wait to find out.

Photo credit: Jim DeMain