“It seems such a contradiction, really,” says Shirley Collins with a bright, lively laugh. “I’m such a cheerful person, but I love all these dark songs.” Her new album, a gem titled Lodestar, is full of viscera and violence: drownings and stabbings and poisonings, what might be a bloody disembowelment, and a man dancing on the grave of the woman who rejected his proposal. Most of the songs are hundreds of years old, missives from deep within English history, and Collins sings them with a solemn matter-of-factness that lends heft to the human suffering.

She has been singing these songs for most of her life. In the late 1950s, she joined Alan Lomax on a three-month song-collecting tour of America, which she still speaks of fondly and excitedly. In the 1960s, she was at the vanguard of the English folk revival, recording old tunes in new settings, often a cappella, but sometimes with accompaniment by her sister Dolly Collins. In 1965, she paired with the guitarist Davey Graham for Folk Roots, New Routes, a landmark album that launched several generations of co-ed folk duos.

However, at the end of the 1970s, Collins abruptly stopped singing, recording, and performing. She retired to her cottage in Essex, where she raised her children and kept listening to the old songs. During that time, she developed a reputation as the grand dame of English folk music, inspiring musicians on both sides of the Atlantic, including Billy Bragg, Will Oldham, and the Decemberists’ Colin Meloy (who recorded a covers EP in 2006).

It’s only been in the last few years that she has found her voice again and returned to singing; Lodestar is her first record in nearly 40 years, and it’s one of the best and most welcome comebacks of 2016, a bright spot in a sorry year. The time away has added some grain and texture to her voice, which is lower and less steady than it was in the ‘60s and ‘70s but still careful in its phrasing and sensitive to the material — not just the human horrors contained in the songs, but the long histories they represent.

When you’re singing a song that’s several centuries old, are you thinking about the real people who might have sung it? Are you thinking about characters?

Not necessarily. You connect with the songs, but they’re not personal songs. What you’re doing is passing them on. You’re slightly removed from them, in a way, because we don’t sell songs, people who sing folk music. We don’t sell it. We don’t push it at you. We let you come to it, so I think it retains its essence. You don’t have to sing them in front of an audience, necessarily.

I just feel these people behind me — the people who have sung the songs down through centuries — and they know them by heart. I want to treat them with a warm respect and present them with the best accompaniments I can make, then just let people make up their minds about the songs. Just sing them as straight as I can, no embellishments really. Because that’s not the way we English sing, really. The Irish have great deal of ornamentation in their singing, but the English don’t. It’s just a different tradition. We sing the songs quite straightforwardly, but that doesn’t mean they’re not crammed with emotion. I think they are.

Singing these songs sounds like a very immersive experience for you, like you’re being swallowed up by history.

That’s absolutely right. You focus in on the song and you inhabit it, as well, but without it being pretentious. I can’t bear it when people show off when they’re singing or get too dramatic and overload a song. I just sing it as straightforwardly as I can, but recognizing that virtually every song has a fantastic history. So I feel responsible for doing the best I can with them. That, in one way, is why I stopped singing for so long: I felt I wasn’t doing the songs justice, and I couldn’t quite bear that. It was very difficult.

In what way?

My voice wasn’t up to it, for quite a long time. And I had a very bad marriage breakdown. My husband had left me for another woman almost overnight. I was singing in public every night at the National Theater with the [Albion Band]. We had a promenade audience right in front of us, and I was in such a state of heartbreak that, some nights, I opened my mouth to sing and I would croak. My voice would break or nothing would come out at all. Martin Carthy, who was also in the band, would help me out on those nights. Some nights it was fine, but it just got more and more scary because I didn’t know what was going to happen. I kept trying and trying, but finally I felt I couldn’t put myself through it and I can’t put the songs through it, either. I had two kids to bring up, so I had to find another job for quite a long time. But a friend said to me, "You listen to field recordings of old singers, and you don’t mind their voices being old." No, I guess I don’t. In fact, I love it. So I summoned up all my courage and started singing again. So here I am again and happy about that.

Do you revisit your old recordings? Especially for something like the new version of “Death and the Lady,” which you recorded in 1970.

I recorded that in the first instance with Dolly, my sister who did arrangements for flute and organ. Why did I go back to it? It’s a song that’s haunted me for ages. A musician friend of mine named David Tibet persuaded me, after some years of asking if I would sing at one of his concerts. He kept saying, "Just one or two songs." It was the first time I had sung in public for some time, and I knew I could manage to sing “Death and the Lady” because it wasn’t a huge range. I’d slightly altered the tune anyway. David played it on guitar, and it just felt so appropriate. It’s so dark, and there’s a real sinister quality to it, so I decided to put that one on the album.

Ian [Kearey], the guitarist who also produced the album, he and I meet regularly. It was Autumn and we were rehearsing “Death,” and I suddenly broke into a Muddy Waters version of it. You know “Mannish Boy,” of course. When I got to the verse about death, the verse that goes, “My name is death,” I went, “I spell it D. E. A. T. H.” I don’t think it’s disrespectful, really. It’s such a strong song that it can take it.

These songs provide such wonderful raw material. You can mold it into something new without losing its integrity.

Some purists might not like it, but it worked really well. The thought of death stalking the country is quite relevant these days, isn’t it? There’s so much many horror. Some people think that song comes from the time of the Black Death in Europe, when death really was stalking the land. Whether that’s true or not, I don’t know. It might be even older.

Were you choosing songs with any particular thematic criteria in mind?

We started off just with the first song, “Awake Awake Sweet England,” the penitential ballad, and it just grew from there. I jotted down one or two songs that I really like and had never really sung, like the “Banks of Green Willow,” which is a favorite of mine. It was collected here in Sussex, but I had never sung it and I wanted to. I had three or four songs jotted down, and then other things just filtered through into my mind. Other songs, like the last one, “The Silver Swan,” we used to sing it at home when we were children. Just the three of us: Mum, my sister Dolly, and me. It’s a five-part madrigal, and I was given the bass part or the tenor part because I had a deeper voice than mum or Dolly. When Ian and all of us were sitting around the table talking about the album, for some reason it just slipped into my head. I just sang it and everybody said, "We’ve got to do that." Every once in a while, there’s a bit of real good fortune and the right song comes to the forefront of your mind. You might have been lodging somewhere in the back of your mind for too long and suddenly it pops up and says, "Sing me! Sing me!"

I’m very pleased that I’ve recorded two American songs. Both were songs that Alan Lomax and I collected when I was over there in 1959. I actually collected “Pretty Polly” in Arkansas from Ollie Gilbert, who was a wonderful mountain singer. That’s a lively song about the American War of Independence — and I’m on your side! Otherwise, the songs are all English.

Do you know a singer named Horton Barker? He was in his 70s when we were there. He was recording a song for Alan called “The Rich Irish Lady,” and he forgot the words. He got halfway through singing it in a very gentle and beautiful way, but then he forgot the words. He said to Alan, "I’m sorry, sir. I can’t go on." And Alan said very gently to him, "Can you speak the words?" And he did. So there’s the complete ballad, half sung and half spoken. I have it and I put it all together with Horton’s tune and recorded it.

That song definitely has an Appalachian flare, especially with the coda.

That’s where it came from. It came from Virginia. And then, of course, we tacked on a fiddle tune from Kentucky on the end, and I will just tell you that, when we were in the studio listening to the playbacks, there was a young engineer there, and he listened to the words of the song — “I’ll dance on your grave, when you’re laid in the earth.” He turned to me and said, "He doesn’t mean it, does he?" And then the fiddle tune comes in hard and strong, and he said, "Ah, yes, he does mean it!" It’s great, because it means we achieved what we meant to.

I’m always surprised by how dark and brutal some of these songs are.

It’s not the most cheerful album, but then so many folk songs aren’t cheerful anyway. The thing is, every single subject was sung about in folk songs, so some of them are very dark and very brutal. It’s extraordinary for many of us that people wanted to still sing them, but they still do. There’s a sort of courage in it: You can sing about murders and suicides and revenge and Lord knows what, and it’s all acceptable. In fact, I find those songs particularly fascinating because they own up to what human beings are.

On the other hand, there are also songs of great beauty. There are gentler ones. I love them all. I’ve always loved old things. I loved history when I was in school. I just love the age of some of this stuff and how it’s clung over the centuries. This is before words or tunes were written down and before there were field recordings. People just sang them and they learned them by heart, because a lot of the English laboring class in the countryside couldn’t read or write. So they had to learn them by heart. The songs must have been important for them to do that. Because of that, there are thousands of songs that are still around.

What I’ve learned from the folk albums of the ‘60s and your recordings, in particular, is that these songs document a history that we can all take part in simply by singing and play them.

It’s a great social history. There’s always that behind it. It’s so valuable. In a way, it’s a bit like archaeology: You dig up the ground and you find something remarkable, even if it’s just a piece of pottery from medieval times. That’s how I feel about this stuff: You find it and it should be treasured. Like the very first song on the album, “Awake Awake Sweet England,” which was written in the 1560. There was an earthquake in the center of England, but it was a big enough one that some of the tremors reached London and toppled part of old St. Paul’s Cathedral. So this chap, Thomas Deloney, wrote a song warning the people to improve their behavior and look to God to become more righteous. This was God’s judgment on them, sending an earthquake. That happened! But I hadn’t ever heard of it until I found it in the book Folk Songs of Herefordshire from 1907, and it was in that book because Vaughan Williams heard it sung by a farmer and his wife in Herefordshire. Where had it been in the meantime? But there they were, this farmer and his wife, singing it 400 years later. It’s extraordinary, isn’t it? I’m bowled over by the wonder of it all.

Not only does it survive after so many centuries, but it still seems relevant today. “Awake Awake” could have been written about Brexit.

Nothing really changes. Well, certain things change. Lives are much easier now, but there are certain deep truths that never change. They’re permanent. People are so different nowadays, but deep down, we all must have something in common.

Tell me about your trip to America. That seems to have informed Lodestar .

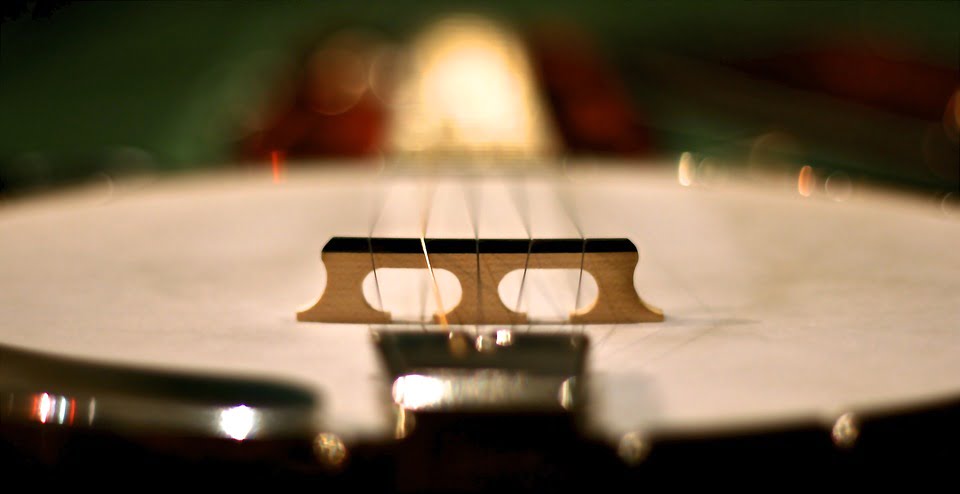

I did have a wonderful time in America when I was there in 1959. I remember hearing the Stanley Brothers for the very first time, I think at a fiddle gathering in Virginia. I was on my feet! There were the Stanley Brothers in their Stetson hats and their smart maroon suits and playing something virtually impossible on a banjo. I was on my feet clapping and cheering. I had never seen anything quite so exciting as that. Those memories are still very vivid, despite it being such a long time ago. The music made such a great impression on me. So did the people I met. I was so fortunate to be on that trip, at that time, when there were still enough people in the mountains singing the way they always had done and playing wonderful old fiddle tunes. That was just the most incredible experience and just reinforced everything that I was starting to learn about traditional songs. It reinforced the wonder and the beauty and the excitement of it.

Where did you travel?

We started in Tennessee, then went up into Kentucky and down to Alabama and Mississippi, where we recorded for the first time Mississippi Fred McDowell. Then we went down to the Georgia Sea Islands to record the people who lived on St. Simons. It was quite a comprehensive trip, and it took us three months. And I’ve been to Arkansas, where we met Jimmy Driftwood, whom I absolutely loved, and Almeda Riddle, who is perhaps the greatest singer I’ve ever heard in my life. She sings some wonderful ballads and love songs, and they’re absolutely haunting.

It was a great experience just meeting people of that generation. I was just 23 when I was there, and I was meeting people in their 60s and 70s. It was such an honor to hear them sing and make friends with them. They were often thrilled, as well, to meet us, especially people like Almeda and Ollie Gilbert. When they sang a ballad, I was able to sing the English version that is still going in England. They were so delighted to know that the songs were still being sung back at home. They spoke of England as the old country. I think perhaps, at that time, they thought the interest in songs and old singers was fading a bit, so it was wonderful to share that with them. About 15 years ago, I wrote a book about it called America Over the Water, so it’s absolutely been kept alive in my mind in the freshest way possible.

One other thing about Almeda Riddle singing: She was right deep in Arkansas, and she’d never see the sea in her life. She sang a ballad called “The Merry Golden Tree,” which is a song about unpleasant happenings on the high seas, set in times of galleons — probably older than that. When she sang the chorus — “As she sailed upon the low and the lonesome low, as she sailed upon the lonely low lands seas” — the way Almeda sang it, you could just see a seascape. She just brought the sea right in front of you, though she’d never seen it. That’s just the power of words and the power of music and the power of the voice. I get goosebumps when I think about that now.

Do these songs change for you or reveal new meanings or significance that you hadn’t caught before?

I think perhaps I appreciate them even more than I did at first because, when you’re young, you’re a little bit superficial, aren’t you? Because you don’t know much. But it all still holds up so wonderfully and I get very emotionally attached to it, too. It’s a great tug of memory for me to go back to when I was a young woman in America and I’d never left home before. It was quite extraordinary, really. I went over on a boat because that was cheaper than flying. Flying was for film stars, and going on a boat was for ordinary people. Quite the reverse nowadays. But I think I still have the more or less same response, but an even greater admiration for it and an even greater emotional attachment to it — which I don’t think I’ll ever lose.

There is one thing I wish I’d learned to do, and that was Appalachian flatfooting or buckdancing. Oh, I wish I’d learned to do that when I was in America. I think it’s magical stuff, but it’s beyond me now for sure.

Photo credit: Eva Vermandel