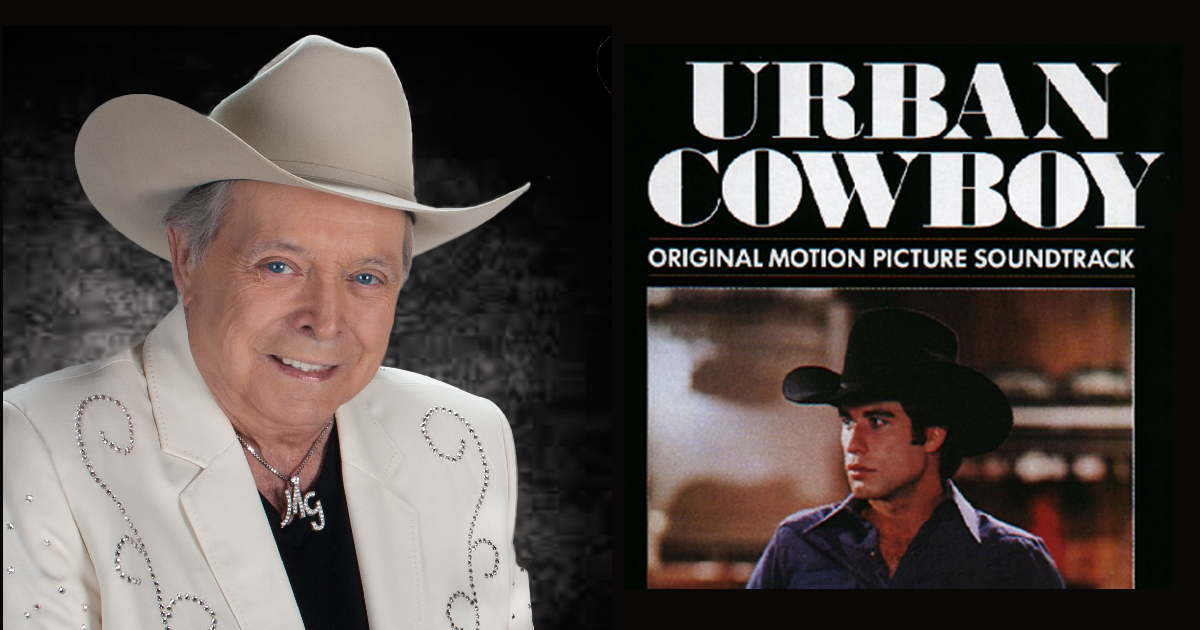

The career of singer-songwriter Ronnie Milsap has been remarkably inclusive from an idiomatic standpoint, even if it’s also accurate to say his greatest acclaim has come within country circles. But over the course of five plus decades in the performing and recording arena, Milsap has also toured with James Brown and Ray Charles, been a pianist for JJ Cale, had R&B hits – with songs penned by Ashford & Simpson or previously recorded by Chuck Jackson – cut successful gospel and adult contemporary songs and albums, and even worked the oldies circuit while covering ’50s classic rock and roll and doo-wop.

Still, it’s his poignant, soul-tinged country tunes that have made Ronnie Milsap so beloved, while earning him induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame and membership in the Grand Ole Opry. A two-time Country Music Association Male Vocalist of the Year, Milsap also helped induct longtime friend and mentor Charles (who once encouraged him to choose music over law school) into the Country Hall of Fame. During the ’70s and ’80s Milsap enjoyed a frequent presence on the country charts, and during the ’80s scored thirteen of his thirty-five number one hits.

Even as times and tastes changed, Milsap adapted and continued to enjoy success through the ’90s and into the next millennium. Now, at 80, he recently decided it was time to call a halt to performing in Music City. Pausing a couple of weeks before his final Nashville show at Bridgestone Arena October 3, Milsap told BGS that there’s one idiom he loves that folks don’t often cite or acknowledge when discussing his influences.

“Man I love bluegrass too,” Milsap said. “Those harmonies, the melodies, that’s a sound that I’ve always enjoyed. Some people didn’t understand exactly where ‘Smoky Mountain Rain’ came from, but that’s the influence. Also gospel is a big influence and of course, I’ve always loved country and soul music. All of it I just absorbed and worked into my own style.”

That sound, an inspired blend of mellow tone and emphatic delivery has made the list of unforgettable Milsap tunes a lengthy one: “(There’s) No Gettin’ Over Me,” “Pure Love,” “Only One Love In My Live,” “(I’m A) Stand By My Woman Man,” or “Daydreams About Night Things,” to cite just five of his numerous hits. Milsap has managed the difficult task of being both sentimental and evocative, never letting his vocals become maudlin or exaggerated, and always credible and persuasive in his stories and testimonies.

Milsap’s also maintained a healthy interest in contemporary happenings and performers, as evidenced by his 2018 LP The Duets, which he called “one of my favorites.”

“Man I love that Kelly Clarkson,” he added. “She’s fantastic. Working with her was a thrill and I love how she sings. Ricky Skaggs, he’s one of the all-time greatest musicians I’ve ever seen and heard. He’s incredible. There are still so many good young singers out there and great musicians in Nashville. It’s a real pleasure to hear them, and I’m so happy about this show coming up. It’s such an honor.”

The last Milsap concert was billed as “The Final Nashville Show,” and a packed house filled Bridgestone Arena two weeks ago. Twenty-nine artists across the country spectrum performed 30 tunes to mark Milsap’s 50 years. The event was co-hosted by radio veterans Storme Warren (The Big 615) and Bill Cody (WSM), while such luminaries as Reba McEntire, Dolly Parton, Clint Black, and Luke Bryan whose schedules didn’t permit them to attend or participate sent videotaped tributes. In addition, prior to the show, new Nashville mayor Freddie O’Connell declared it “Ronnie Milsap Day,” and Tennessee governor Bill Lee added an official proclamation honoring Milsap’s “Final Nashville Show.”

Depending on personal perspective and taste, there were multiple highlights. One contemporary star who got maximum exposure and delivered a powerhouse performance was Scotty McCreery, whose version of “Pure Love” was a big audience winner, as was Randy Houser’s “Don’t You Ever Get Tired (of Hurting Me)” and Trace Adkins’ “She Keeps the Home Fires Burning.”

Kelly Clarkson’s “It Was Almost Like a Song” was a show stopper, as powerful and dynamic as anything anyone did during the evening, and a rousing rebuttal to those who think her iconic daytime status protects another overrated celebrity. A pair of surprises were gospel vocalist/pianist Gordon Mote and contemporary Christian star Steven Curtis Chapman. Both took secular tunes and soared on them; Mote on “Lost In the Fifties Tonight (In the Still of the Night)” and Chapman on “What a Difference You’ve Made In My Life.”

View this post on Instagram

Band of Heathen’s rendition of “Houston Solution” and Breland’s cover of “Any Day Now” got polite applause, while rousing songs performed by Sara Evans (“Let’s Take the Long Way Around the World,”), The McCrary Sisters (“Stand By Me,” and also appearing backing Clarkson), Terri Clark (“My Love”) and Lorrie Morgan (“I’d Be A Legend In My Time”) reaffirmed the appeal Milsap’s best tunes have had for both men and women vocalists. Elizabeth Cook’s “Nobody Likes Sad Songs” added another element, that of a fresh, lesser known but emerging artist enhancing her reputation with a strong and impressive performance.

Appropriately, the guest of honor closed the show, and while Milsap at 80 isn’t the singer he was in his prime, he remains an effective entertainer. His closing set began with “Smoky Mountain Rain,” and also included “America the Beautiful,” “Stranger In My House,” and “There’s No Getting Over Me.” The night ended with a stage full of the performers who’d previously paid homage to Milsap backing him on an engaging version of the Rolling Stones’ “Honky Tonk Woman.”

Throughout the evening, all the performers were superbly supported by the Nashville session band Sixwire, augmented by special guests like the great Country Music Hall of Famer Charlie McCoy and saxophonist/steel guitarist John Heinrich, a longtime Milsap band member. It was a memorable night, and a wonderful celebration of a premier American musical talent.

View this post on Instagram

Photo courtesy of Gold Mountain Entertainment