The humble appearance of the Station Inn could never give away the enormity of its legacy and importance to bluegrass music. Nestled between skyscrapers in an ever-growing city, a single story cinder-block building with its windows painted shut sticks out as a relic from the past — when the Urban Outfitters across the street used to be an empty field of waist-high grass.

For nearly 50 years “the World Famous” Station Inn has played a pivotal role in bluegrass as both a venue and community hub, drawing people to Nashville and making connections that had a major impact on the music. Through the rest of 2021, The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum will honor and present the history and legacy of the venue in their exhibit The Station Inn: Bluegrass Beacon.

“The main reason that we wanted to do this exhibit is because the Station is such a vital and important part of not just Nashville music history, but of American music history,” says Peter Cooper, one of the curators of the new exhibit. The Station Inn has a larger-than-life reputation in the bluegrass community, but this new exhibit endeavors to highlight both the importance of the venue’s history and its welcoming atmosphere.

It was founded in 1974 by a group of bluegrass musicians and singers — Bob and Ingrid Fowler, Marty and Charmaine Lanham, Jim Bornstein, and Red and Bird Lee Smith — who wanted to provide their fellow musicians and fans with a venue where they could play and hear bluegrass music. At that time the Station was more of a clubhouse where the owners functioned as the house band and guests would come up to jam. They moved to the current location in 1978; three years later, the club was bought by J.T. Gray, who at the time was driving Jimmy Martin’s tour bus.

Gray, who would go on to be inducted into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame in 2020 and was given a lifetime achievement award by the Southeast Regional Folk Alliance, began booking national touring acts to perform. It would be easy and accurate to show why the Inn is significant by pointing to the artists who have played there, including Bill Monroe, the Stanley Brothers, Vince Gill, Alison Krauss, and essentially any other important name in bluegrass. But the clubhouse atmosphere always remained. Countless (as in absolutely too many to count) threads of bluegrass history, both well-known and overlooked, can all be traced back to chance meetings at the Station Inn. J.T. Gray fostered a welcoming atmosphere that led to many locals and visitors from out of town to meet there, including mandolinist Mike Compton.

“I rode up [to Nashville] with Raymond Huffmaster, a bluegrass guy from Meridian, Mississippi, where I’m from, because I’d been hanging around him trying to learn how to play,” Compton says. They visited the bluegrass spots in town including the Station Inn, and Compton recalls after heading home, “Pat Enright got in touch with me and said they were starting a band and asked if I wanted to join. So I moved [to Nashville] in 1977 and moved in with J.T. Gray.”

Mike and Pat would continue playing together and later go on to form the legendary Nashville Bluegrass Band, which became a staple act at the Station Inn. A predecessor to that award-winning band was performing at the Station the first time future bluegrass star, Kathy Chiavola, came to town in 1979.

“When that door opened, the room was packed and I saw a vision of heaven,” she says, recalling that first night. “I heard these two voices, Alan [O’Bryant] and Pat [Enright], in their prime. And I lost it. I said, ‘OK. I’m moving here.’ There was a notice on the Station Inn bulletin board that a band of women playing bluegrass were looking for a roommate.” That band turned out to be the Bushwhackers, which featured bluegrass pioneers Susie Monick and Ginger Boatwright. Chiavola eventually joined the Bushwhackers playing bass and singing lead and harmony until Doug Dillard moved to Nashville. As the banjo player from the Dillards (who were famous for playing the Darlings on The Andy Griffith Show), Dillard put a band together and asked Ginger Boatwright to join, and about a year later asked Chiavola, too. Both the Bushwhackers and the Doug Dillard Band would frequently perform at the Station.

Chiavola eventually moved into a duplex next to bluegrass bassist Mark Schatz. Together, they would often play the Station Inn with Charlie Cushman, Stuart Duncan, and Bobby Clark as part of a band called The Satellites. Other times, Chiavola would perform at the Inn with an ensemble called the Lucky Dogs which featured Jerry Douglas, Béla Fleck, Edgar Meyer (who had just moved to town), and sometimes Sam Bush or Mark O’Connor.

“It was beyond belief,” she says. “Sometimes I remember being on stage at the Station and listening to those guys play. I thought it was the most heavenly sound — I can’t even describe it to you. It was perfect music with so much feeling. You could hear a pin drop. It was so beautiful.”

Schatz, on the other hand, often performed at the Station with Mike Compton as part of John Hartford’s band. Hartford had moved back to Nashville to form a string band after a successful songwriting career in L.A. That California connection later landed him the contract to help with the music for the Coen Brothers’ massively successful O Brother, Where Art Thou? Compton’s 1927 Gibson A-Jr. model mandolin, which he played with the Nashville Bluegrass Band, in John Hartford’s string band, and on the O Brother soundtrack, is included in the new exhibit.

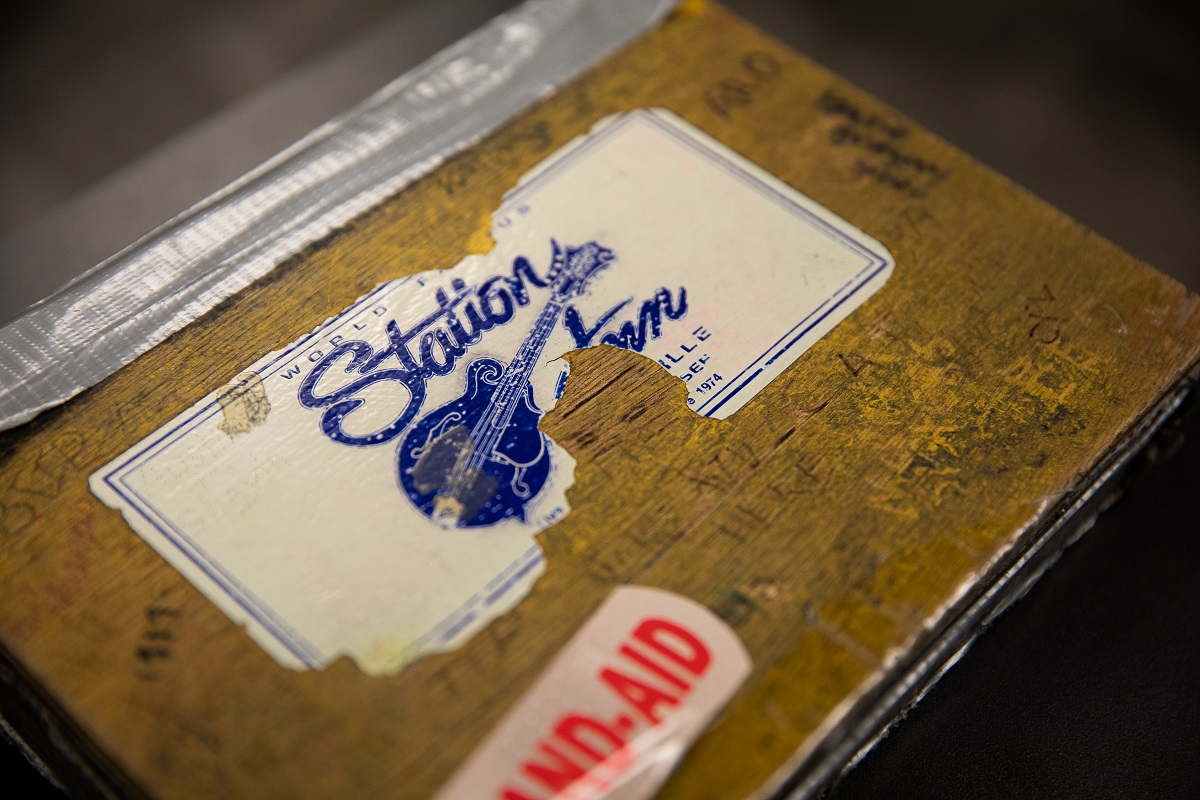

Also on display is a small wooden box that was used to collect admission for years, along with some history about former Station Inn employee and local folk icon, Ann Soyars. “Ann embodied what the Station is about,” Cooper says. Soyars worked the door and was “small but fierce.” She was known to throw out rowdy college football players for being too loud, but also welcome regulars and newcomers alike. “Ann’s inclusion in the exhibit is indicative of what we’re trying to do, which is to help people understand not just the facts of the matter, but the spirit of the matter. The Station Inn is an example of musical community building in the most positive way. It’s like Cheers for ‘grassers.”

In addition, the exhibit features other artifacts from both the building and the musicians who have performed there including a fiddle played extensively by Tammy Rogers with the SteelDrivers, Mike Bub’s Kay M-1 double bass, which he played with many groups at The Station Inn — including Weary Hearts (Chris Jones, Butch Baldassari, Ron Block), the Del McCoury Band, and the Sidemen (Terry Eldridge, Jimmy Campbell, Ronnie McCoury, Gene Wooten, Ed Dye, Kristin Scott Benson, and Larry Perkins). Seats from a tour bus used by Lester Flatt, which serve as seating in the venue, are on view as well.

Generations of performers’ children have grown up in the Station’s green room and backstage and have gone on to perform on stage as adults. Newspaper has been put down on the bar to admire someone’s new puppies. Great care has been taken to lovingly craft the perfectly reheated pizza. Beers are shared by locals and honored guests after the doors are closed to the public. (And I have hidden fancy decaf coffee and a pour-over in the back that I take out when I visit.) To this day the Station Inn is a community gathering place where friendships, bands, and lifelong loves of bluegrass are formed. It embodies not only the authenticity of the music but of the community. And often, everyone knows your name.

Editor’s Notes: The Station Inn has endeavored to safely present live music throughout the pandemic. They have reopened to live audiences at a limited capacity and live stream performances through their web portal stationinntv.com.

The Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum will present The Station Inn: Bluegrass Beacon until January 2, 2022. The museum is currently open to the public at a limited capacity.

Photo of Station Inn and artifacts: Emma Delevante for the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

Other photos: Charmaine Lanham