Right now, no band is blending country and punk music better than Vandoliers. Although that mash-up has been attempted for decades, it’s rare to actually find a band that disregards the rules completely and still sounds like they just might belong in a late-night honky-tonk. For years and years, that’s likely where you would find this Dallas/Fort Worth-based band. And if you’re gonna play in Texas, as the old country song goes, you’ve gotta have a fiddle in the band. While that instrument does provide a definitive fire to their show, it’s just one component to an invigorating sound that sets them apart on the local landscape.

However, the band has tapped into a market well beyond Texas, hitting the road with artists like Flogging Molly, Lucero, Old 97s, and their own personal heroes, Turnpike Troubadours. When the group’s European tour kept getting delayed during Covid, a disc jockey in Spain kept playing their songs anyway, and by the time they wound up in Madrid, they were selling out clubs to crowds who knew every word. Beyond just singing along with “Every Saturday Night,” which they’d heard on the radio for years by this point, the Spanish fans were almost certainly responding to the blasting, somewhat unexpected trumpet solos that punctuate anthemic songs like “Before the Fall.”

Most impressive of all, they managed to bottle up their on-stage energy and inject it into their first album in three years, The Vandoliers. While the band had a day off in Lawrence, Kansas, lead singer and principle songwriter Joshua Fleming filled us in about their first time at the Ryman Auditorium, kinda learning how to play guitar, and the unmistakable influence of country star Marty Stuart.

BGS: When I saw you at the Ryman, what struck me the most was your showmanship. You guys were full throttle from the moment you walked out there. What does it feel like in those moments before the stage lights hit you?

Fleming: We play this song [backstage] called “Urban Struggle” by the Vandals, and it’s an old punk song from the ‘80s. Evidently there were two clubs — a punk bar and a country bar — that were right next to each other, and that song is about the fight that would ensue because of that. Every time that comes on, we all just get super excited. It’s really those moments of excitement. Like at the Ryman, I had a moment where I went out back and hung out in the alley where all the musicians hung out before the show. I’ve been doing this thing where I’ve been writing a tour journal, and I wrote a little paragraph. Instead of posting it on Twitter or Instagram, I have this little book that I’ve been writing in, just trying to gather my thoughts, because there’s been those moments.

Like when we first started, when people would tell us we weren’t country enough, which they were probably right, you know? But we love that music so much and we love that heritage and we love that legacy. This is just how we get to be a part of it, by sounding like this, because that’s just where we’re from. I’m not from the hollers or the hills of Kentucky, or anything like that. I’m not from Nashville, Tennessee. I’m kind of stuck in the middle between Fort Worth and Dallas. … That’s where I grew up, so this is just the sound that I love, and these are things that remind me of Texas and where I’m from. When you get to play at the Ryman, especially for a band like Turnpike, who’s been a massive influence on us, and being accepted by your peers after seven years of kind of being the red-headed stepchild, it’s really surreal!

Do you have any influences in terms of the way you present yourself on stage? Did you ever see a band and say, “THAT’S what I want to do!”?

All the time! We’ve played a lot of empty bars and had to get people out of their chairs to get the excitement. We’ve also gotten to learn tricks from Old 97s, Lucero, and Flogging Molly, and those bands kind of taught us and showed us the ropes of how to put on a show and get people moving. When I was out with Flogging Molly, Dave [King, the lead singer] just completely commands not only the crowd’s emotions, but also their bodies. He can get their hands up, waving, and they can get people moving. And with Lucero, every Lucero show is just the crowd singing Lucero songs with Lucero. I saw that and I was like, “THAT’S the kind of show I want.” What I really want is a cathartic release and if I’m lucky enough to write some songs that people want to sing with me, that means a lot.

This was my first time seeing you and I noticed you don’t spend a lot of time on stage banter.

Oh yeah. I hate banter! I come from the Ramones school of “1-2-3-4, ‘Good night!’” I want every song to sound like they run into each other. I don’t want that energy to stop. I don’t want to shut the crowd out; I just don’t want to turn it into this soapbox because I want to play as many songs as possible.

I was very surprised that Turnpike gave us an hour at the Ryman. I had [prepared for] a 45-minute set so I actually got to add songs instead of take away, and that was super fun. But I shoved 16 songs into an hour. I think I gave myself three minutes to say our band name. And tune. [laughs] And to say thank you to Turnpike because they’re the reason we were there. It was really great that they allowed us to be a part of their coming back. We played their first two shows at Cain’s and those were amazing. But playing the Ryman, I mean, it was their first night at the Ryman, too, so we got to share that feeling together. That was such a cool bro thing to do. [laughs]

I read an interview where you said Marty Stuart was the reason you started the band. What did you mean by that?

I mean, I’m constantly learning and there’s so much music I don’t know. And when I found Marty Stuart, it was this perfect time. Hank III was on his show and I just gotten into Hank III. Marty Stuart is a Hall of Famer and absolutely brilliant but he wasn’t quite as in-your-face as other artists I had seen and heard all my life. So, when I discovered him, it was through The Marty Stuart Show. I watched the episode with Hank III, and I was like, “This is RAD! This is rockin’!” There’s an electric guitar up there and he’s ripping — Kenny Vaughan is up there, just crushing. And their harmonies were perfect. Harry Stinson is of the best singers ever while also being one of the best drummers. It’s really unfair that they’re so talented!

My wife and I, one of our favorite bands is T-Rex, so that glam rock thing was very fresh in my mind at that time, because we had just met and I was showing her these records. We walked down the aisle to The Slider and “Metal Guru” was the song. I really love glam rock. So, anyway, I see the glam in Marty. I see the talent. I see the stories. It was everything that I loved from all of these different genres, and also very traditional and amazing.

So, I run in to find my wife, who’s a huge country fan, and I’m like, “Look at this guy! He looks like a country Marc Bolan!” She’s like, “Oh, that’s Marty Stuart. He’s awesome.” And goes back to bed like it’s no big deal. [laughs] I got obsessed and watched every episode of that show and bought records and tapes and CDs. And one day I got to open for him, going out with them for three shows with him in Texas, and he was one of the kindest people in the world. He is so cool and everybody in that band is the coolest. If Marty Stuart can accept me and be kind to me, then the sky’s the limit, right?

When did you learn to play guitar?

I started banging out chords when I was, like, 11. I wasn’t very interested in being a virtuoso, like a guitar-solo guy. I was more into that outlet to speak and write my feelings out. And I also really liked the idea of being in a band. I played sports but there was always somebody on the bench. No one’s on the bench in a band. Everybody gets to play and it gives you a little bit of a social scene, too. Those were the things that I was really interested in at the time. I started my first band when I was 12. I played roller rinks and movie theaters and little DIY shows for all the kids in my middle school. And then I moved to high school and I played all-ages clubs and theaters with my ska band. Then I moved into cutting records and learning about recording and going to school for recording. It’s been a long journey.

So, did I “learn guitar”? Kinda. I learned how to write a song and I learned how to be in a band — and it’s been great! I think that’s why I liked punk in the beginning because it made me feel like I could do it. I didn’t have to worry about having some pedigree. I didn’t have to be the son of some famous dad. I was from a small town very far away from L.A., Nashville, New York, and Chicago. It was more of just me being able to have a little place in my social scene and it kind of grew from there. Then I started touring and traveling.

Is that where the song “Sixteen years” comes from?

Yeah, that’s actually exactly it. You can take it any way you want, but in the song, story-wise, my dad’s not a preacher. That’s actually referencing one of my songs from my punk band, The Phuss. Like, “A poor man’s song that no one wanted to hear” was “Bottom Dollar Boy,” which we re-recorded for Bloodshot, but it came out on our first EP that didn’t sell very many. [laughs] I wasn’t famous because of that song but I really love that song. It’s just referencing trial and error, trial and error, trial and error. And it’s not about being successful. It’s just about doing it. So, even if it takes me forever, I’m still going to do it. And even if I don’t even make it, whatever that means, I would still do it. I love it so much.

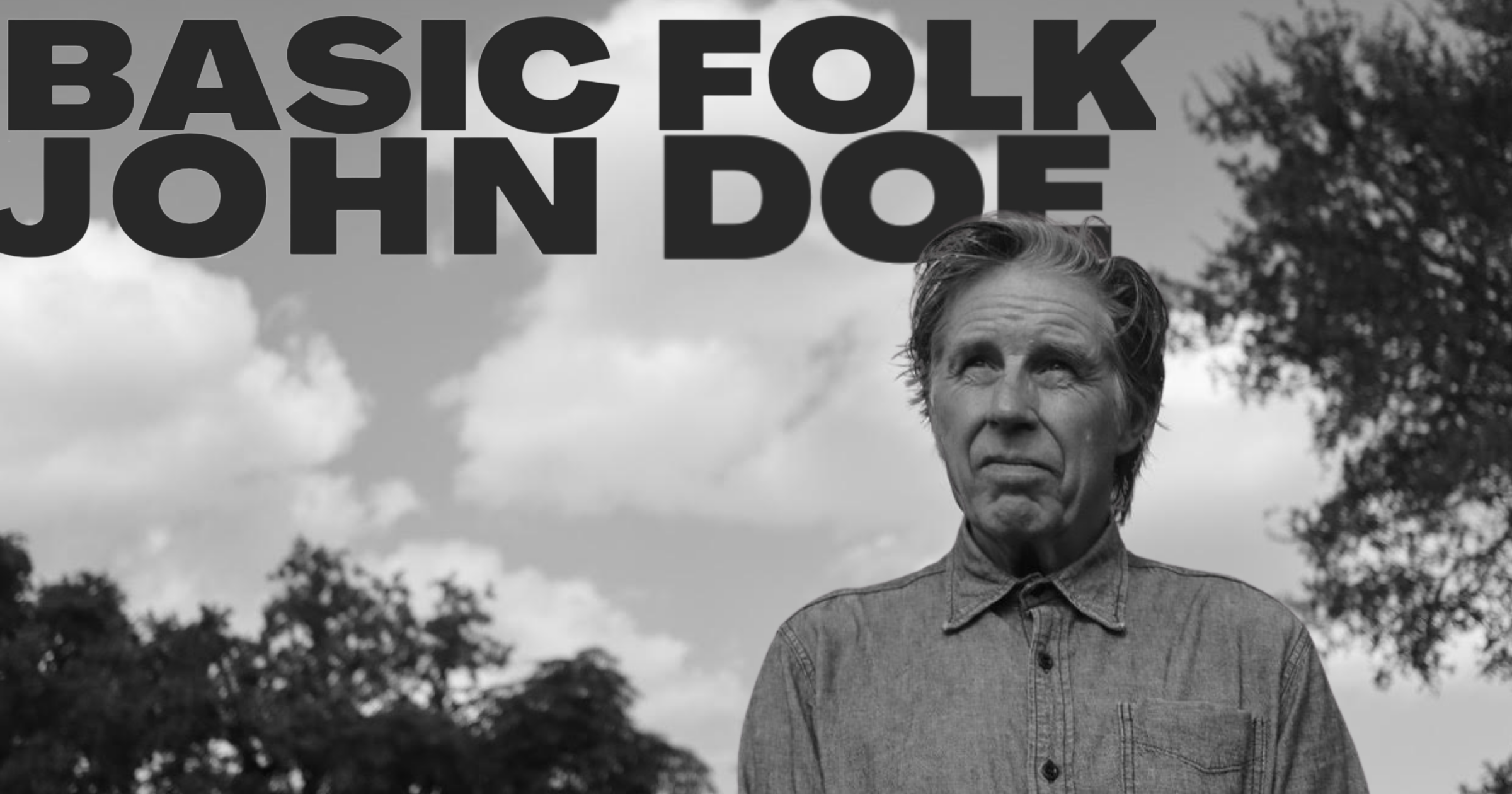

Photo Credit: Rico DeLeon