Joy Clark and Ani DiFranco connected over something unexpected: a Christmas song. Slated to perform at the same benefit show in 2022, the two singer-songwriter-guitarists were grouped to take the stage together and needed a holiday tune, ideally an original one. Clark’s “Gumbo Christmas” made it to DiFranco before the show, and the legendary artist and founder of Righteous Babe Records heard a hit. Once the pair synced up, they felt an instant musical kinship, and it wouldn’t be long before DiFranco signed Clark to her label.

Last October, Clark released her critically acclaimed debut album, Tell It to the Wind. Informed by her experience as a side player and imbued with a deep reverence for her craft as a solo artist, the record was one of 2024’s finest releases, announcing Clark as an artist with a keen sense of who she is and what she wants to create. The album sonically pulls from Clark’s roots as a Louisiana native and thematically from her experiences as a Black and queer woman making her way through the world. Highlights include “Lesson,” a bluesy, groovy reminder to keep your head up in the face of struggle, and the record’s vulnerable closing title track.

Before the holiday break, BGS caught up with DiFranco and Clark over Zoom to chat about Clark’s signing to Righteous Babe, her album Tell It to the Wind, and what she and DiFranco admire most in one another – as they prepare to hit the road together on tour next month.

Let’s start by having you share how you met and what drew you to one another.

Joy Clark: Well, it started with a Christmas song. It was 2022, and we were both on a Christmas show. There was a big lineup, with Big Freedia, John Goodman, and a lot of other people. So, they tried to group the performers together and I got grouped with Ani and Dayna Kurtz, and I happen to have a Christmas song called “Gumbo Christmas.” My agent contacted me and said, “Hey, can you make a recording of your song and send it to Ani?” He sent it to Ani and I heard back that it was a hit. She liked the song. So, they grouped us together and we performed it.

Ani DiFranco: It’s a total hit, this song. I mean, I don’t understand why people are not holding hands all over America singing this song right now.

JC: I wrote about my grandmother making gumbo every Christmas, it got to Ani, and I think that’s how I got on the radar.

AD: From my perspective, I’m asked to do a benefit and it’s just tons of New Orleans usual suspects involved, like she said. Then, I found out a little later everybody had to play Christmas songs for this thing. I was thinking I’d just show up and play a song or two of my own. I’m like, “Oh, man, Christmas. What the hell?” So, I’m combing through Christmas songs, and I’m like, “I don’t know.” And then I thought, “Oh, I’ll just write one. I’ll write a Christmas song.” I pounded my head against that wall for a few days and discovered that it’s harder than you think to write a Christmas song that anybody ever wants to hear.

Finally, somebody rescued me by saying, “Well, you know, Joy’s got a Christmas song. Maybe you could sing with Joy Clark.” And in comes this little video of Joy singing. I was like, “Oh, my God, that’s the best. That’s the best.” Now I know how hard it is to write a Christmas song, so my respect for this woman is already right up here for making this sweet, soulful Christmas song. And then [Joy] came and recorded it.

You don’t hear many artists getting signed off a Christmas song or even having that be their entry point to meeting their eventual label. That’s a great story.

AD: It was also just hooking up, you know, in person, doing a little rehearsal at Joy’s house, and then going and doing the gig. We got to hang out. It’s not just like I heard the song somewhere. I got to see firsthand that Joy can play and sing her ass off and was an artist in the world doing her thing. I always say that we’re not really a label with tons of resources that can create something out of nothing, or market somebody into existence or something. But what we can do is support working artists and try to get behind them and help facilitate what they’re already doing.

JC: I think that’s the cool part, because I’ve been a working musician for a long time. And not just being Joy Clark, just writing my songs and performing – I played in a lot of different bands, playing guitar, singing harmony. … I’ve really just been working, been doing the thing. I played as a side person for a long time, which is how you learn. That’s how you learn to just be a musician. I feel like that’s been a gift for me. So, now to be able to just to step out up front and write and put out music, I feel pretty lucky. But it also feels really right.

It sounds like you came into the picture with a fully realized sense of who you are and the kind of music you make and what you want to do. And it sounds like the label is a great home for artists like that, who already have strong senses of self and don’t necessarily need, like you mentioned, Ani, a lot of development and marketing.

AD: Certainly at Righteous Babe, you’re not going to have some pencil pusher telling you what you should do with your songs. The thing about an artist-run label is the artist has to follow their heart. That much is clear at Righteous Babe.

Joy, I’m going back to what you were saying a moment ago about being a side player and the opportunities that provides – or sometimes forces – for you to adapt and learn and be able to do things on the fly. How do you feel that those experiences have shaped your solo work?

JC: There’s pressure in it, but then there’s not really pressure, too, because it’s not about me. I think it allows me to just be and not think about, “What do I look like?” or “How do I feel about this certain thing?” It’s giving somebody else space to do their thing. And that gave me a lot of confidence, actually. It gave me a lot of freedom. … I think that helped me step into my work, because when you do need people, when you do need support, you get both sides of it. I think it’s made me more compassionate. I hope I’m not an ass. I don’t think I’m an asshole. [Laughs] I understand what it is to support somebody’s work.

AD: I can really relate, too. I remember the first time I worked on somebody else’s record that wasn’t my shit, and I was like, “Whoa. This is all the fun of making music without the crushing emotional baggage of exposing your guts and putting yourself up for judgment.” So, I completely hear what you’re saying about how it’s a different experience to make music when you’re not on the hot seat, when it’s not you being judged. I love working on other people’s music for exactly that reason. It’s so freeing emotionally. … And now we’re about to go out to make some live music together. That will be fun times.

I wanted to ask about that. As you get ready to hit the road together, is there anything you can share about your plans, or what you’re looking forward to, in particular, about getting to share a bill with one another?

AD: Another thing that is always in the back of my mind with Righteous Babe, if we’re considering releasing a record, is whether this is an artist we could have the means to help. Somebody came to us with a very different genre of music recently and it was a super cool record, but I just thought, “I don’t know how to get to the right audience and get this project where it needs to go.” But from the minute I met Joy and saw her play and interact with an audience, I thought to myself, “My audience will love this person.” So, that’s always in the back of my mind, like, if we put out a record on Righteous Babe, could we do shows together? That’s a really easy way for me to assemble a bunch of people and then point, “Look at her. Check this out.” I just know that they’ll eat you up, Joy. And I haven’t told you yet, but I was hoping to ask you if we could play a song or two together.

JC: Of course! Just let me know what you want. I’ve already been listening. You know it.

AD: I’ll text them to you.

JC: One thing I’m looking forward to is being on a bus. My dates have been fly, pick up a car, then drive, you know? And it’s not like I have a right hand. It’s me and my guitar, driving. When I’m driving, I can’t do anything.

AD: And it’s exhausting. Most of your energy is zapped when you get to the gig.

JC: Yeah, it’s like, “Can I just sit in the green room? Can I just recover from that?” I’m looking forward to having that tour experience of being on a bus and chatting it up and maybe even writing. We’ll see if I can actually write on the road.

AD: Yeah, you need a certain amount of space just to do that, like your own dressing room and your own hotel room. It’s so hard when you’re just out there driving around, doing all the things. Funnily enough, Joy and I were just at another benefit the other night, both playing a tribute to Irma Thomas, singing Irma Thomas songs and benefiting the New Orleans Musicians’ Clinic. We were joking and I was like, “You got to be careful because once you get on that bus, it’s so hard to get off.”

JC: I can feel that coming. I’m looking forward, too, because I’ve really only seen Ani perform once, at French Quarter Fest in 2023. Now, I get to check out the show night after night.

Ani, you mentioned a moment ago that feeling of knowing that your audience will love Joy’s music. I see a lot of connection points in what both of you do. There’s a lot of vulnerability there, for one – I think you described it as “exposing your guts” earlier, Ani, and that feels true for both of you, at least from my perspective as a listener. What points of connection do you see in one another’s music?

JC: I think Ani is a badass guitarist. I respect that, because it takes a lot to be able to play with the band and then to just be a person on stage with a guitar. I think I really connect with that fingerstyle picking. I prefer fingerstyle because it gives you a lot of different textures and it gives you different choices. Instead of strum – a strum is great, it’s just when you can pick, there are these other things happening. These little flavors and lines that I connect with, because that’s the type of player I am. I don’t have the picks on my fingers, it’s just my fingers. But I think that’s how I connect [to the instrument].

AD: Ditto for me. Keep those naked fingers, because it sounds so much better. I put on these plastic nails, but that’s just because I get so violent with my guitar and I bloody myself if I don’t have them. But the sound is so, so great with the real finger and the real nail. I’m really more of a rhythm player, and I just sort of play by ear, but you can play solos. You know what key we’re in and what the notes are supposed to go with that – all the things that I don’t actually freaking know. [Laughs]

I’m just super impressed with anybody who can legitimately play guitar like you do. There’s knowing how to play or knowing how to sing or this or that, and then there’s knowing how to stand there alone on stage and hold an audience. And Joy can do that, too.

I’m glad y’all brought up each other’s guitar playing, because there’s clearly so much passion and care there for both of you. And I don’t think we ask musicians about their instruments enough. People ask a lot of questions about songwriting and lyrics but not so much about, say, devising chord progressions. How does incorporating guitar into your songs work for each of you?

JC: It’s always different. When I write, there is no one way that it comes. But there is a feeling. There are colors that appear. Sometimes, there are sounds that come out. But one thing that I can say, for me, is that [writing] happens simultaneously with messing around on a guitar. I often sing as I play. I’m not usually writing. I do write, but the core of it is a feeling. If it’s something sentimental, then sentimental lines appear. Sometimes it happens if I’m driving, then I pick up my phone and I hum, and then when I pick up the guitar, I’m flowing. There’s an improvisation that happens and it’s a little bit mysterious. I don’t really understand it. It’s just mystery. But I love chords and I love to pick out cool shit. Then, I just put words to the thing that I’m picking.

AD: I can basically relate to everything you’re saying. Same for me. It’s different all the time. There’s no, like, set process, of course, and each song happens in a different way. But generally, it’s just being able to hang out with your instrument and just be with your guitar, hang out, and process your feelings with it. I miss that myself in life these days. I’m older and at a different point in my road than Joy. And I, many moments, wish I could put myself back where you are, Joy, just embarking on something and being really focused and having that guitar by your side all the time. Now, my kids are in the way most of the time, you know? [Laughs] … But that’s really what it is, having a relationship with the guitar that deepens and deepens. The understanding between you and this instrument deepens, and the guitar starts finishing your sentences.

JC: You can find some really pretty jewels in something that didn’t really feel good [while] writing it. But I want something to grow on me. Maybe it doesn’t fit so perfectly, but in time, “Oh, yeah, that does make sense.”

AD: I feel like that’s what you want for other people, too. It’s not necessarily to always be making songs that are instantly like, “Oh, Skittles! It’s sweet and fruity.” But, something that, maybe, on repeated listens, it takes its time to get under somebody’s skin. Then it really lives there. … What I’ve learned over many years and many albums and hundreds of songs is that, even after you get back to your disillusionment or you sour on something that’s not new anymore, you just have to have faith that somebody out there in the world is still going to have that first experience that you had with it. Somebody is going to feel that way about it, even if it’s not you anymore.

That feels like a lovely place to wrap. Before we sign off, do you have any parting words for one another?

JC: I’m really freaking grateful. I’ve been doing my work and I feel pretty lucky that people want to hear what I have to say. And I feel really lucky to have an album out on Righteous Babe, on your label, Ani. I feel like it’s right. I just turned 40 a couple months ago, and I think it’s pretty fantastic to feel like I’ve just started.

AD: Well, I would say – in a way that’s not weird, in a way that [reflects] that we’re on the same level – that I’m proud of you. It makes me so happy to see you stepping into yourself and your music and stepping out there in the world. You’ve paid a lot of dues and you completely deserve this moment. I can’t wait to see what’s next.

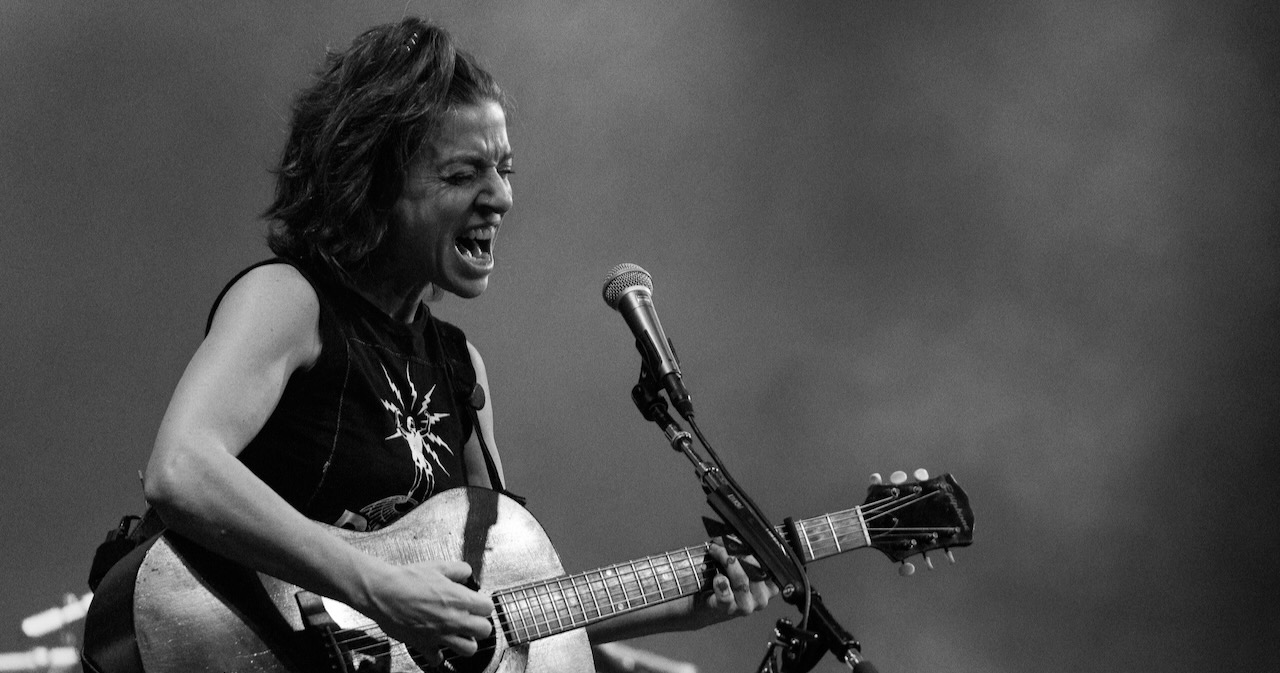

Photo Credit: Joy Clark by Steve Rapport; Ani DiFranco by Shervin Lainez.