Offa Rex began with a daydream. Colin Meloy, best known as frontman for the Decemberists, was driving his car around Portland, Oregon, and blasting No Roses by the Albion Dance Band. “I was marveling at the interplay between Ashley Hutchings’ arrangement work and Shirley Collins’ vocals,” he recalls with the geeky glee of a metalhead describing a Randy Rhoads guitar solo. Then he experienced the kind of epiphany that typically strikes more fans than performers: “It was like a light bulb turning on. I wanted to be in the Albion Dance Band!”

His was an impossible dream. The Dance Band, a loose supergroup of English folkies active during the 1970s, is no more. “I don’t have a time machine, but I have a band and I know somebody who sings really beautiful English folk music. Together, perhaps we could not only discover and re-evaluate old folk songs, but also pay homage to that era of music making.”

That “somebody” was Olivia Chaney, a London-based folk singer who straddles the trad and new folk scenes in England. Following the release of her full-length debut, 2015’s The Longest River, she toured with the Decemberists and left an impression on the band, especially its frontman. Open to the idea of collaborating on a folk-revival record (or is it a folk-revival-revival record?), Chaney joined the Decemberists in Portland for rehearsals and recording sessions

Thus was Offa Rex born, taking their name from the eighth-century Anglo-Saxon king. Their debut, The Queen of Hearts, collects new recordings of old tunes, with Meloy and Chaney trading off vocals. Some are fairly well known, such as “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” written by Ewan MacColl but popularized (in the States, at least) by the R&B singer Roberta Flack. Other choices will be perfectly obscure to Yankee listeners, such as “Flash Company,” a 19th-century tune about the dangers of stylish cliques best known from a 1980 album by June Tabor and Martin Simpson that is long out of print.

The Queen of Hearts is a curious album: UK songs filtered through a U.S. lens, a transatlantic exchange between Americans enamored with British folk music and a Brit so thoroughly embedded in that scene that she felt compelled to ask permission from her idols to cover their songs. More than that, it argues for an inescapably political aspect to this music, which is never merely decorous, as it harkens back to a very different Albion of the past. At a time when both Meloy’s America and Chaney’s England are experiencing similar convulsions of identity — Brexit over there, 45 over here — the act of singing these old songs raises questions of appropriation and nationalism that the musicians are still pondering as they prepare for an extensive tour.

For that reason, The Queen of Hearts sounds heavier and timelier than your typical covers album, although Meloy insists they undertook the project primarily for fun. “This was something we just wanted to do, not because we felt there was an audience for it, but because it was a grand experiment and a creative journey.” Will Offa Rex produce an heir? “Certainly, there are more folk songs out there to be sung.”

Tell me about the transatlantic nature of this project. How did that inform the concept of Offa Rex?

Olivia Chaney: The funny thing between Colin and me has been a to-ing and fro-ing of what he sometimes wittily describes as his almost fantasy of this project and then, for me, the reality of actually still knowing, if not working with, some of the people who made some of the records that we both know and love. For example, No Roses, I’d been doing a tribute project to that specific record with some of the people who’d been on it. Ashley and Shirley are both friends. Sometimes it was tough for me because I’d fear their judgment, but sometimes it was a really nice thing because it felt like a hand into the past. Obviously, it was a great honor to be invited by Colin to come and do this, and an interesting transatlantic conversation ensued.

Colin Meloy: The target I was going for was not necessarily realistic, and the aim was not really aping a record from the ‘60s or early ‘70s. What we came out with, potentially in some ways, you could find a place in time for it, but so much of it is also filtered through our influences as people who weren’t necessarily even alive at that time. Inevitably, it becomes something different and new. We were keeping each other in check and created something wholly different than what we had set out to do.

It wasn’t just the re-creation. You were trying to make it about interpretation.

CM: I quickly realized, even though it might be soul satisfying just to sit down and re-create note-for-note the Anne Briggs dual bouzouki/voice version of “Willie O’Winsbury,” nothing could’ve been more boring. You already have that. I think that was also the spirit of the folk revival itself — not only in England but in America. You had this group of standards that everybody was playing with and putting their indelible marks on, even if they were doing, for the most part, similar arrangements. In some ways, the interpretations would be drastically different and, in some ways, it was just incremental steps. I feel like the version of Anne’s “Willie O’Winsbury” versus John Renbourn’s, they’re really closely related and yet feel miles apart.

A lot of contemporary folk groups seem to be confronting that distinction: How do you get past the revival to the raw material?

OC: For me, a bit of a personal irony is that I get called very trad. Even though I grew up listening to a lot of the second revival records, I didn’t, and still don’t, regard myself as trad compared to lots of people in the real deep English folk scene. My interest is in contemporary classical music and other songwriters who were pushing boundaries — that’s often the way I come at trying to reinterpret traditional songs. That’s what interests me. So it was good, Colin and I working together, because we’d keep a check on each other’s agenda and hopefully meet somewhere in the middle.

CM: I don’t know if purism is really the thing because, if we were being purists, we would be in a barn singing a cappella in front of a shitty microphone and …

OC: Colin, we were in a barn.

CM: That’s right. We were in a barn. We had that much going for us. It’s not necessarily purist, but you’re always going for what you feel is right and organic. In popular music, there is a time-honored conversation between the English and Americans — not only in the folk world, but certainly in R&B and rock ‘n’ roll. Both sides of the Atlantic have informed the other. Sometimes the person who seems least qualified to approach a certain kind of music inevitably injects something interesting into it. I feel like there’s so much discussion going on about the dangers of cultural appropriation, and that’s something that we talked about in regard to Offa Rex. I imagine that accusation could be leveled at us. Other than having our token Englishwoman fronting the band, we’re definitely guilty of cultural appropriation. We’ll see how people respond.

Folk music has always been tied to a national identity. Especially at a time when Brexit and other things are changing that identity, this album potentially reflects that change in an interesting way.

OC: I’m obviously very English, but really, in some ways, ethnically or in terms of my upbringing, I’m quite a mongrel, as well. I am interested in a sense in cultural identity — or going back to certain roots of different cultures. Folk music often is such a profound expression of a culture or a people. It’s quite a strange mix of things in that sense, as well, the record.

Do cultural purism and musical purism lead to the same dead ends? Sorry, this is getting really deep.

CM: It is really getting deep, but I think it does. If you put boundaries around everything, innovation becomes more difficult. We’re seeing that, if you really want to get political, in our own country, the idea of shutting out immigrants and immigration will do real harm to the sciences and to culture. We need new input for innovation. Particularly for the fraying relationship between America and England, maybe this is a bridge. We’re going to bring America and England back together. [Laughs]

This music is obviously linked to a certain place and a certain culture. With that in mind, I’m curious about the decision to record in Portland, as opposed to some old farm in Northumbria.

OC: I think there was probably some logistical, practical …

CM: Financial …

OC: Exactly.

CM: We were working on a budget. Also, the environment that you create something in can have a profound effect on the outcome. We rehearsed it in the country outside of Portland, in Willamette Valley — very western America. And then we recorded it in Portland with Tucker Martine. All of that created a flavor that’s going to offset whatever sort of Britishisms are there in the music and create a different color altogether, hopefully.

What can you tell me then about choosing these songs? Did you have criteria in mind for a finished product? Or were they just songs you wanted to sing?

CM: We both just made wish lists from the outset. She came out in the summer and we sat around and listened to a lot of records. Then we went away and listened to each other’s wish lists and hemmed and hawed about things — something’s too familiar or it’s not familiar enough.

OC: There were a few songs that I ended up doing that were almost soloistic, and those ones tended be ones that Colin had maybe not commissioned me to do, but certainly gave me license to do. My fear was that the criticism from my own people on the folk scene in the UK would be that we had done too many of the tried-and-tested classics. But then we both agreed that there’s nothing wrong with that. I don’t think I would’ve had the bravery to come up with something like “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.” I didn’t quite realize it could fit the brief, but Colin was very decisive and clear that he thought that would be a great one to do. I’m really happy that we did it.

CM: That came from a place of relative ignorance. I thought I was really steeped in this music, but now I feel like I’m barely breaking the surface. I was like, “Let’s do ‘Fine Horseman’ and give it the pulpits it deserves.” But Olivia said, “No, everybody does ‘Fine Horseman.’” It’s funny: In America, Lal Waterson’s “Fine Horseman” is as obscure as it gets on a record that been out of print for years — although I saw that Domino is reissuing it. But that song is more well known in England. That was something to keep mind — that certain songs I felt were ripe for re-evaluation were considered too familiar by Olivia. It was really a question of finding a balance. Is this a rediscovery record? Or is it a standards record? I think we did a little bit of both.

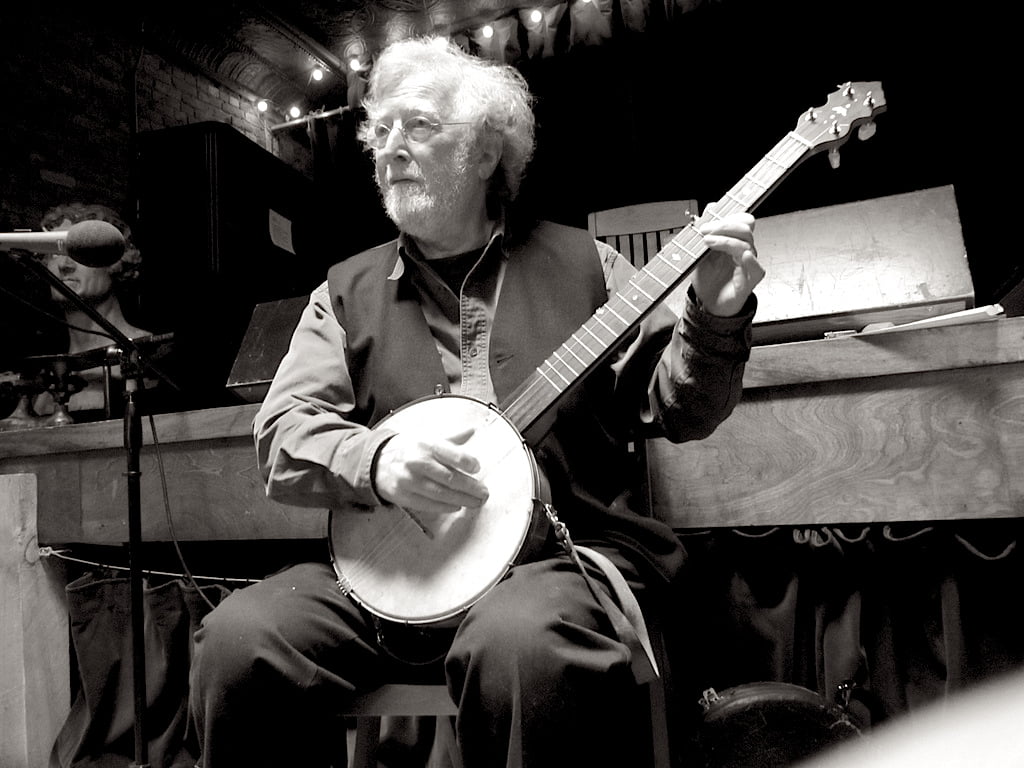

OC: With someone like Lal Waterson, when I got off the phone with Colin, I had to ring Eliza Carthy, Lal’s niece. I felt I had to seek the family’s permission, if we were going to do one of Lal’s songs. It was just a funny expression of the situation; we were both coming from such differences places and experiences in relation to the music. Me, coming from a tiny island, I’m inevitably going to know half the people who sang or wrote those songs.

Is that something you did with other songs? Did you feel compelled to seek permission or guidance from the originators?

OC: Yes. I had a really interesting correspondence with Andy Irvine about a few songs I did for a new Kronos Quartet record. Some of it’s trad singers, but some are just artists on Nonesuch Records. I did a version of an old Irish song, “You Rambling Boys of Pleasure,” which I learnt from an Andy Irvine recording. I combined asking him about the origins of that song with talking to him about “Willie O’Winsbury” which, rumor has it, he taught Anne Briggs. Also, I did some shows with Norma Waterson and Martin Carthy very recently and was asking Martin about the song “Queen of Hearts.” I think it’s my issue of needing to seek approval from elders and experts. That’s my big hang-up, and Colin certainly was trying to kindly beat that out of me.

CM: I wanted you to be in the cone of silence and not have any interaction because you would just be intimidated. Inevitably, it would influence the process. But that may be the American dilettante in me. Covering a song, I’d never really sought permission and maybe that’s a bad thing. It is more of an American attitude, although I did appreciate getting some sort of approval from the MacColls when we did “First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.”

OC: I would be pretty terrified as to what Peggy Seeger would actually say about it. I saw her on a BBC program which, Colin, I still need to send you. It’s for some anniversary of the song and they’re interviewing her and playing the Roberta Flack version in the background. Peggy is quite a force of nature, as I’m sure you both know. She basically says, “I don’t really like most of the versions,” and I don’t think she’s a huge fan of the Roberta Flack version, either. But her son, Neil MacColl, is a friend and a wonderful musician, plus he’s a big Decemberists fan. He loved the fact that I was doing the project at all with Colin and thought it was a really wonderful idea. I’m excited to play it for him — just not his mum.

That song was one, in particular, I wanted to ask you about. It always feels like the “Mustang Sally” of folk tunes. Everybody covers it. It’s very popular. But this version sounds very fresh, especially with that flickering drone in the background.

OC: That’s the weird tremolo stop on my little Indian harmonium. It’s really magical, that sound.

CM: It’s got a good psychedelic bent. I wouldn’t go so far as to call it the “Mustang Sally” of English folk music, although I do think that people associate it with the Roberta Flack version. I didn’t know that it was actually written by Ewan MacColl, until I was studying the liner notes of some Atlantic R&B compilation and saw Ewan MacColl had written this beautiful, smoky R&B tune. This is the same guy who had written “Dirty Old Town,” which I had known from the Pogues. So there was this weird line between these two things. I heard Peggy’s version much later, which has this beautiful, almost naïve art approach to it — a piece of folk art in her inimitable way of singing and phrasing. To my mind, this project was an opportunity to strike a balance between those two and maybe make something new there. Olivia did a phenomenal job of that. It was beautiful.

OC: I don’t know about that. But, again, this is an example of where I don’t feel like a pure folkie. Although I know the son of Ewan and Peggy, and work with a lot of those people in that scene and love traditional British folk music, it’s certainly not the only influence on me or the only music I grew up on. I grew up on the Roberta Flack version. I used to lock myself in my room and listen to her record. I was a massive fan. I felt like I really had both strands and very consciously tried to pay homage to both. And, again, I was kindly bullied by Tucker and Colin not to do 160 takes, but actually live with possibly the second or the third.

CM: For many, many versions of “First Time Ever I Saw Your Face,” the Roberta Flack version is the source material, whereas we really made an effort to take the Peggy Seeger version as our source material. Maybe that’s part of the process, too: Rather than going off the last version of a song that’s been done in an effort to move the needle forward, we went back even further and hoped that would lead us down a different road.

You mentioned not doing 160 takes of a song. Did you have to adjust your process working with the Decemberists?

OC: Yes. Especially since we were working to tape, it was quite an eye opener for me and really challenged the way I approach making music. There were just some really hilarious moments, specifically on “Flash Company.” We’d get to the end of a take, and I would look at everyone and be all kinds of “Oh, God. That was a disaster. We’ve got to do it again!” And they’d all be high-fiving and going, “Yeah. We’ve got it in the bag.” “Are you serious? What the hell?” Then they’d be bummed out by me being bummed out by my own singing, but eventually I’d have a slow epiphany that maybe there was some truth in the fact that actually that first take was quite lovely. It took me a while to get there.

I love the way that song leads into “Old Churchyard.” Musically, it’s a nice moment, but, thematically, it’s pretty powerful to have those two songs tied together and talking about the nature of life and death.

CM: It does work, thematically. In my head, it’s like, “Oh, it’s in the same key and we can drone into the next one.” But it is kind of like a pilgrim’s progress a little bit.

OC: I used to sing that song a cappella at gigs. When I first started singing traditional music, I was not playing folk clubs at all and I’ve never really done the hardcore folk circuit ever. I was just playing strange DIY hipster venues around East London, which certainly wouldn’t be the kind of place where they’d expect to hear an a cappella religious song. It was a good way to shut a room up and get them listening in a way that they might not otherwise. The song has got a very ping-pong transatlantic journey, because I knew that song from the Waterson:Carthy record. The Watersons learnt that song from an old American singer, when they were traveling around America. Of course, it would have originally come from the British Isles, but then become an American folk song. I think it’s gone to and fro across the Atlantic Ocean many times.

CM: Sort of like a game of telephone — with each pass, the song distorts a little more.