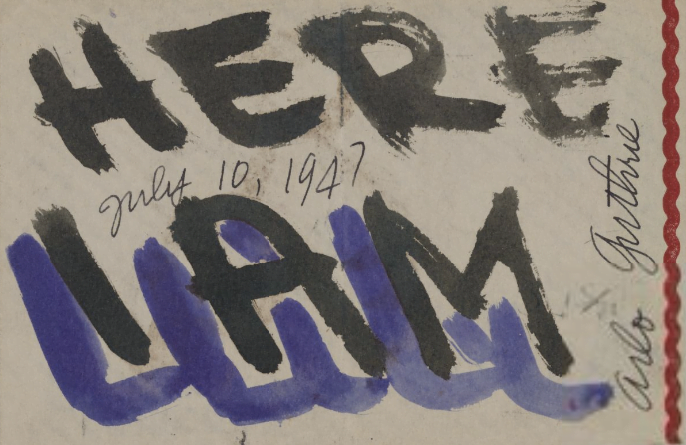

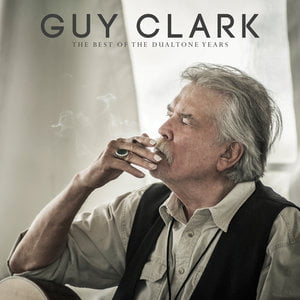

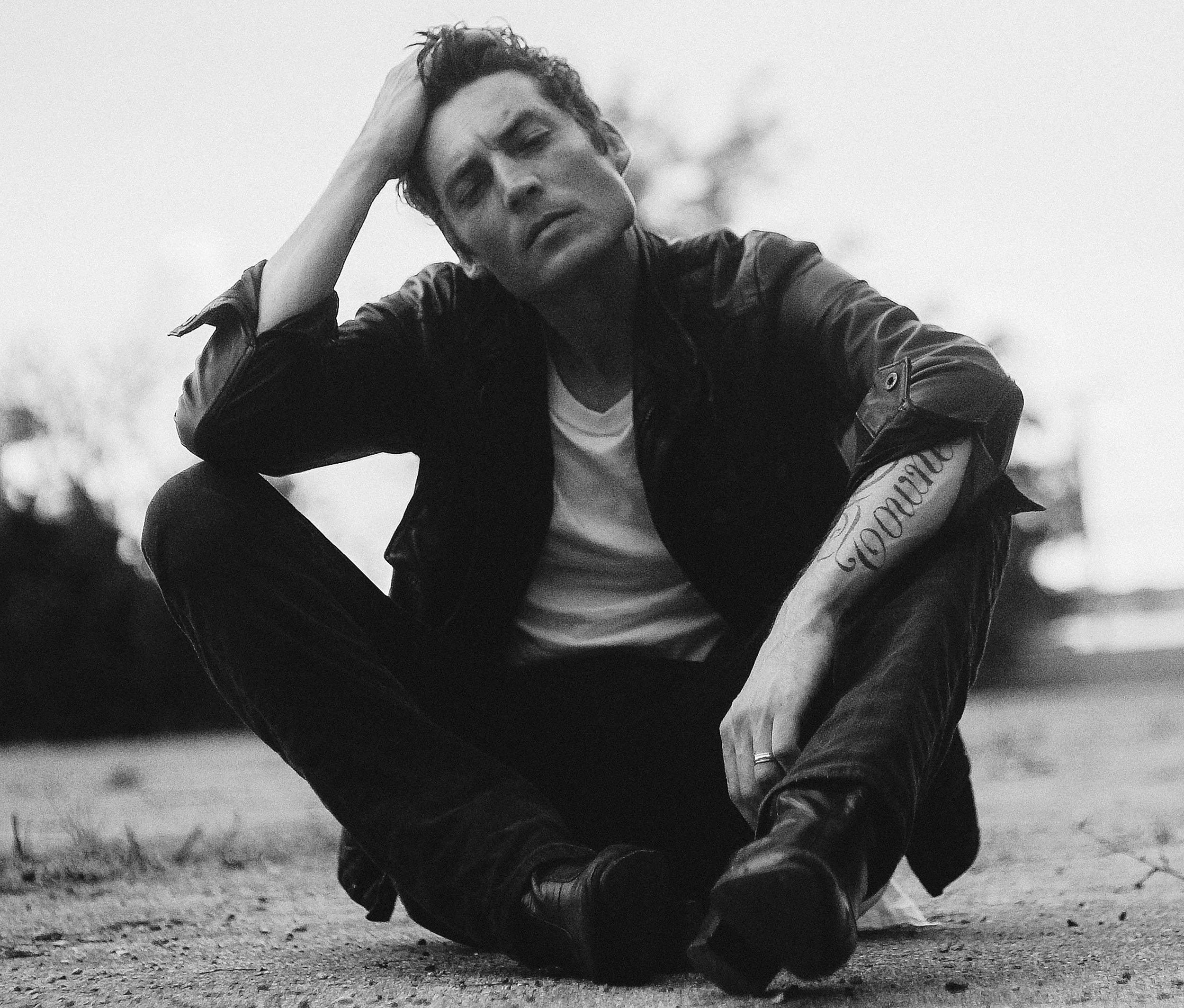

After more than a decade at the heart of Augustana, Dan Layus recently released an official solo album, Dangerous Things. And anyone who thinks they are going to get another bunch of roots-rock anthems out of Layus has another think coming their way. The sparsely drawn, country-tinged singer/songwriter set summons Gram Parsons, Woody Guthrie, and early Tom Waits as its patron saints, and Layus's Rodney Crowell-esque voice feels right at home in the form. There's a fragility to the whole artistic affair, but one which makes it clear that there's strength in being vulnerable, in asking for or offering help.

I dig this record. A lot. And I'll tell you why: It has a serious lack of pretense. It's not trying to be anything that it's not. You're just putting it out there with nothing to hide behind. How's that feeling?

I appreciate that. Without sounding pretentious, ironically, that's exactly what I was going for — to, essentially, go for nothing. [Laughs] It's like Seinfeld; it's a show about nothing. That's probably my favorite compliment about the record. Thank you. That's very intuitive and a little bit left-of-center approach to describe it. And that's absolutely what I was going for.

Let me put it this way: It felt far too predictable to say, “I think I'm gonna make a country record now. That seems like the thing to do.” It felt like that would've been laughed off the map. Being a self-described narcissist, I know that I care a little too much about what people think sometimes, especially music people. So I needed to challenge myself … I'm joking about the narcissism, by the way. [Laughs]

[Laughs] Yeah, yeah. I gotcha.

I hoped you would. I needed to let go of a lot of the practices — the writing practices, sonic habits I had in the past. It's very easy to fall into a pattern of crutches, when it comes to music. You get used to certain elements around you. Even things as simple as “Where do the drums go on this song? What's the bass gonna do?” — assuming that there needs to be these four cornerstones of a record that make the sound of the record. I think what I was able to do — and it was a greater challenge than I thought — was to just not worry about it at all. Just rely on the characters in the songs, let them be themselves.

I won't lie: I'm absolutely in love with the few elements, sonically, that are implied and nodded to, as far as pedal steel and fiddle and, of course, the Secret Sisters and the female background vocals. I'm in love with those, but I think the subtleties of them are what make it say, “Yes, this is what you think it is, but I'm not going to stand on top of the building and say, 'I'm a country artist now. Hear me roar!' I'm just going to let it be what it's going to be.”

It seems fitting, too, to leave the band name behind with the big, sweeping melodies and the arena-rock drums fills. Just let that all live in its own world.

Right. Yeah.

Why, for you, was that shift in branding and that shouldering of responsibility important? Because, like I said with the music, there's nothing left to hide behind, brand-wise.

That is true. It was kind of for selfish reasons. Sometimes you forget, at least for me, if I'm a fan of a certain artist or singer that's associated with a band, you forget that they have their own feelings of weight or they're battling with their own self-image in that environment. You forget that. “Oh, I just like the music. I like that band a lot.” You forget there are all these times that, potentially, they don't feel totally comfortable in their own skin underneath that umbrella, that moniker, that brand or band name. It comes with a weight. It comes with an expectation of a certain sound, a certain style, a certain form.

I think what happened was, I put out this last record — the last Augustana record — I made it, essentially, by myself with a few producers. It felt like a desperate plea. I loved the songs, but the album felt completely scattered. I tried my very, very best to be myself in that situation and carry it or be comfortable with it. But it became glaringly obvious, after a few years, that this was done. This was not what it once was. To call it a band and call it what it used to be in 2005 is just silly. I'm lying to myself and to the fans. Times change. Things change. Relationships change. People's careers change. One day you work in a business office and one day you don't want to work there anymore. You need to try something new to feel motivated or excited about something.

So it really is more of a reboot than an evolution, creatively, then?

I think so, yeah. I felt that, creatively and in a career-minded way, Augustana had reached its resting place. I have nothing but wonderful feelings about it. Never felt angry about it. Never felt jealous about other people's standings, maybe people we were coming up with and where they ended up, if they ended up anywhere at all. I was always able to keep that all in perspective.

But I think, for my own benefit and the benefit of my family and our future and definitely my future in music, I felt like, “You know what? Let's live in the current place that we are.” And the current place that I am is that I'm ready to make an album that has my name on it and sounds the way I've always wanted it to sound. And nobody's gonna tell me no, that I can't have pedal steel, that I can't have a fiddle. [Laughs] Nobody's gonna tell me that it sounds too Americana.

[Laughs] And it's a fiddle, damn it. Not a violin.

It's a damn fiddle! [Laughs] Nobody's gonna tell me that this isn't gonna work at alternative radio because it's too alt-country or whatever. I'm just gonna make the damn record sound the way I wanted it to, ever since I heard Gram Parsons or Ryan Adams, when I was 16. That's the record I've always wanted to make, but for whatever reasons, I was never able to fully realize that sound and feel. I feel more at home now, than I ever have.

I think that's going to be reflected in the people who respond to it. I'll be honest, I have a few Augustana songs in my iTunes, but I wasn't that big a fan.

Yeah.

But I seriously love this record. It reminds me of Chely Wright's new one. I was never a commercial country listener, so I knew of her and liked a few of her tunes, but on her new record — it's the same thing — she found her true voice. I feel like that's what you've done.

Awww. Thank you. Thank you very much. I appreciate that very much.

You're welcome. And I don't say that just to say it.

[Laughs] I can tell! I can tell that you mean it.

[Laughs] Now, you've talked about having to let go of songwriting in order to write these songs. Is that because of the personal nature of the songs — that they were for your album and not for a singer to be named later or for a band?

Yeah, that's part of it, certainly. I'd be lying if I said that it wasn't partially my fault for investing a lot of time in co-writing with other people over the last five or six years. Especially in Nashville over the last two to three years.

That's the way it is here.

That's the way it is here. I learned a lot. I learned a lot of good writing habits and I learned a lot of bad writing habits over the course of a few years. And I already had my own style of writing, which a lot of people do, when they come to town. I was writing with people in L.A., too. It just has its own thing to it. Coming to Nashville and being like, “Alright. I'm going to try to get some cuts. Some BIG country cuts. I need to make some damn money for my family. I need to let go of my whole artistic thing, because it ain't working out.” [Laughs] “If I'm a music guy, if that's what I'm gonna do, then I better find a way to support my family with music because I don't know what the hell else I'd be able to do. I know I can write a song, so let me get in with some writers. Let me try to get some cuts.”

And it didn't really work out. I had a hard time letting go of my own … I don't know what it is … my own method. I couldn't just say, “It's for the money. It's worth it.” I was never able to go to the point where I said, “Yeah, this song is worth barely being able to sleep at night.” [Laughs]

[Laughs] Well, it's putting a price tag on your soul, right?

Yeah, it really felt like it. I think, at the end of the day, I found that there were a few songs that really impacted me with some of these writers who I'd met in town. And they made the record. They were close to being cut by other, larger artists in Nashville who passed on them and I was like, “You know what? Then I'm going to do it because this feels like my song.” So there are a few of those cuts on there.

The rest of the record, I wrote myself, which I hadn't done 70 or 80 percent of a record on my own for seven or eight years, so that was part of letting go of the songwriting process that I was referencing. After driving into Nashville from Franklin every day from, essentially, 9 to 5, coming home to dinner after writing a pop-country song or whatever it was, it becomes this occupation, this lackadaisical, mediocre endeavor, if you let it.

At some point in that process, it became that. It became very mediocre, very uninspired, and I realized that I needed to stop and stay at home for a minute and not try to go get cuts and write my own songs. I had to figure out how to write my own songs again, by myself without another writer. It sounds crazy, but I needed to. I became too reliant on the process where the goal is just to finish a song a day. That was a very convoluted perspective to develop and I felt like, “Man, I don't know how I lost my way on this one.” So I took a step back, stayed home, and … I don't know what song it was, but it just broke open the floodgates. I was so proud that I could write a song that I could feel something about, that I wanted to showcase and go play. That's what happened, as far as writing was concerned.

Got it. “You Can Have Mine” … it might be my favorite cut. I'm not sure. There's some competition there.

Ohhhh, wonderful!

It reminds me of that old parable of a friend jumping down in a hole with someone because they know the way out. So I wonder if that is that a role you've played for someone … or had someone play for you? Or if music plays that role for you?

You know what? A little bit of everything. That's one of those songs. Two of these songs are written with a wonderful writer named Emily Wright — “You Can Have Mine” and “Call Me When You Get There.” There was a stretch of a few weeks when we were getting together and writing a bunch. It was a wonderful connection, as far as writing was concerned. We saw things in a similar way. Both of those songs kind of just shot right out and felt really great right away.

“You Can Have Mine” — the title just popped into my head and we just started writing it. So I don't know where it came from, specifically, but it came out of something. It definitely came from experience. At that time, either myself or my wife was battling a pretty heavy bout of stock seasonal depression, I think. Which, living down here, as you know, can be very impactful when January, February come around and money's running low and you're feeling tired and estranged from any feeling of inspiration and kind of a little lost or down. That's something my wife and I, and probably most people, go through — just feeling like you've got someone there to go through it with you, you have somebody to call or go home to or get up for the next day. That's something that I don't think I address as often as I should, these bouts of depression that I feel or that my wife feels.

It is something you explore, though, on this record.

Absolutely.

Like on “Only Gets Darker.” For you, it's not a passive state with a big “Time Heals” light at the end of the tunnel. You have to be an active participant in your own healing, right?

Yes. Yes. That was how I felt about it, and still feel about it. This is a long life. Just because I've been sober for five-plus years doesn't mean that's it. [Laughs] It's a constant struggle for anyone to get out of their own way, essentially. That's the battle every day that I feel I'm fighting. It's not just booze or whatever. It's anything. Just trying to move yourself out of your own way and find a way to appreciate the moment that you have, what's happening around and in front of you, people who love you, people you love. That's a challenge. It's easier to see the things you're not getting or that aren't being given to you.

That song, in particular, I never felt as if … and this is just my perspective, everyone feels differently … but my experience is, seeing yourself out of a dark place or having a hand to help you like in “You Can Have Mine,” that feels like the only way. Not only is it empowering to give you confidence for the next time, but it also just feels like the truth. I mean, I've never just woken up one day and said, “Oh, shit. I feel better.” [Laughs] It's a conscious effort. It's a thought process. It's your actions. It's your choices that help you wind up in a better place, mentally and emotionally. But I don't know. That's just me.

For another folk-country songwriter's perspective, read Kelly's interview with Lori McKenna.

Photo credit: Justin Clough