After singing for over 70 years, you’d think the stories wouldn’t come as easily, or the spirit wouldn’t be as willing, or some other facet of life would come to require greater attention. But if you’re talking about the Blind Boys of Alabama — and especially founding member and octogenarian Jimmy Carter — you’d be wrong. Carter makes up one of two remaining original members (along with Clarence Fountain) of the singing group that got its start at the Alabama Institute for the Negro Blind in the early 20th century, and he’s not ready to quit just yet.

The Blind Boys of Alabama’s new album, Almost Home, nods at the impending end to their journey, but their fervent voices raised together in praise signal a different kind of attitude toward death than typically prevails. It’s a celebration, rather than a worry-driven study, about what exists beyond the known world. Thanks to their faith, they don’t have any doubts in that regard. “He’s been there with me all these years. He’s not about to leave me now,” Carter sings on the title track.

To facilitate their latest album, the Boys’ manager, Charles Driebe, recorded interviews with Carter and Fountain, and then sent out a 30-minute video to an array of lauded songwriters. They received 50 options, which touched on what the men had discussed, and eventually culled that down to 12. John Leventhal and Marc Cohn, Phil Cook, Valerie June, the North Mississippi Allstars, and more contributed to Almost Home, penning songs that touched on the spirit the Boys have long exhibited with their voices. June’s “Train Fare” looks at pain from another angle: Any kind of suffering just deposits more “train fare” in your account so you get where you need to go at the end. While Leventhal and Cohn’s “Stay on the Gospel Side” (taken from Fountain’s recollection) focuses on the offer to become soul singers, and the Boys’ choice to do exactly what the title states. Secular music has never been off-limits for the Boys, though. In fact, they cover Bob Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released” and Billy Joe Shaver’s “Live Forever” on their new project. Carter knows it’s a way to reach younger audiences while slipping in that good news they are still so eager to share. He may be “almost home,” but while he has time and health and strength, he still has a message to spread.

What has it meant for you to use your voice in this way?

I’m a firm believer in God. I feel that everything that has happened to me in life is a blessing from Him. Whatever I have accomplished, I owe it to Him.

It does seem as though you’ve been called to deliver a message.

I believe that, too.

How has your faith strengthened your gratitude and vice versa?

Everything that I have asked Him for, I have received. For example, I told God to “Let my mother live until I get grown,” and he did that. He didn’t only let her live — he let her live to get 103 years old, so she just passed in 2009.

Oh my goodness.

Oh yeah, so I have faith, and I am a believer, too.

One of the stories you shared with songwriters eventually became “Let My Mother Live” on the album. What was it like being able to sing that kind of extreme faith?

The guy that wrote the song, John Leventhal, he surprised me! We were talking about it, and he wrote the song just about as I told him. It was a surprise, but a pleasant one. There’s another one on there called “Stay on the Gospel Side.” It talks about how we had some setbacks along the way, but we didn’t deviate and we didn’t turn back. We stayed on the gospel side. [Laughs]

You absolutely could’ve crossed over, as so many others did.

That’s correct. When Sam Cooke crossed over, we were there at the same time.

In the same studio?

In the same studio, and they gave us the same offer, but we told them, “No, we gonna stay on the gospel side.”

It’s so interesting because you’ve found your own way to do that. In recent years, you’ve incorporated more covers from secular artists.

The reason we incorporated and collaborated with secular artists is because we want the young people to know our music, and the secular artists can relate to young people. We collaborated with people like Ben Harper and Aaron Neville, so now, since we did that, we find that we have more young people attending our concerts than ever before.

I’m sure. When you collaborated with Justin Vernon for your 2013 album, that would’ve also opened up a new audience.

That’s true.

And no matter what, you’re still sharing your message: good news.

I say gospel is the good news of God.

If you could distill your many songs, covers, and albums down to one message about faith, what would it be?

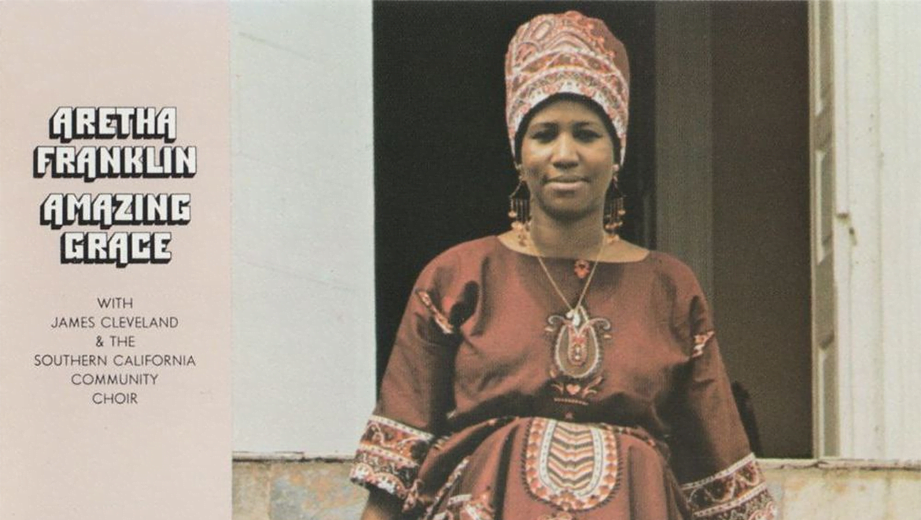

Well, we have a signature song that we do every night, “Amazing Grace.” That tells it all because, but for the grace of God, we wouldn’t be here. We sing that song every night; that’s our testimony. If we come to sing for you and you don’t feel anything, then I feel that we’ve failed you because we want you to feel what we feel. If you came to the program and went back the same way you came, then we failed you. We didn’t do you no good, and we don’t like that. That’s the way it is with us.

So it’s your group mission.

We get tremendous response from the crowd, and that keeps us going. People ask me, “You’ve been doing this for almost seven decades, what keeps you going?” I tell them, “When you love what you do — and we love what we’re doing — that keeps you motivated.”

Doesn’t it just, though? It’s so true.

Yeah, so as long God lets us go, we’re going to keep on going.

It’s amazing, too, how your spirit doesn’t always have to come across in words alone. I saw you in 2015 at Justin Vernon’s inaugural Eaux Claires Festival.

Did you?

Yeah, you sang with the Lone Bellow and, at one point, you were all just humming; I felt it deep in my chest. You can’t make that up!

Yeah, that’s what we like to see. That’s our message: We like to touch people’s lives. I’m glad you felt something.

Thank you for it; it was a beautiful moment. So what has been the most surprising moment of your journey with this group?

Let me say this: When the group started out many, many, many years ago [Laughs], we wasn’t expecting anything. We just went out and did this because we loved to sing gospel music, and we loved to tell the world about Jesus Christ. We weren’t looking for no awards, no accolades, no nothing. But I’ll never forget the first Grammy we got. That was a surprise.

A nice one, hopefully.

A good one! And we got five in a row! Oh, that was good. It took a long time.

Isn’t that funny how it happens?

I always say, “Better late than never.” And then another surprise, we got the chance to go to the White House three times. That was a great experience. We had a chance to sing for three presidents.

If Donald Trump were to be the fourth to invite you, what’s the one song you and the Boys would sing to help him understand a more unifying spirit than he’s been displaying?

I don’t think he’s going to invite us.

I don’t think so either, but just in case …

I would say “Amazing Grace.”

If he didn’t feel anything, we’d surely know something’s up, as if we didn’t already. So with the Valerie June-penned song “Train Fare,” I thought that was such a unique way to look at suffering. What was your take when you first heard it?

I didn’t like it! [Laughs] I didn’t like it because I didn’t understand it. I had to listen to it; it had to grow on me.

That is the case sometimes.

Yeah, but as we listened and we talked about it, we began to understand it. My train fare … when I go through trials and tribulations, I’m paying my train fare. It’s a good song.

And with “Singing Brings Us Closer,” I was struck by the sentiment that invoking songs can bring those we’ve lost closer somehow. Do you have a favorite song you like to sing to bring the memory of your mother closer?

Like I said, our favorite song is “Amazing Grace.”

So across the board, that’s the one?

That’s the one.

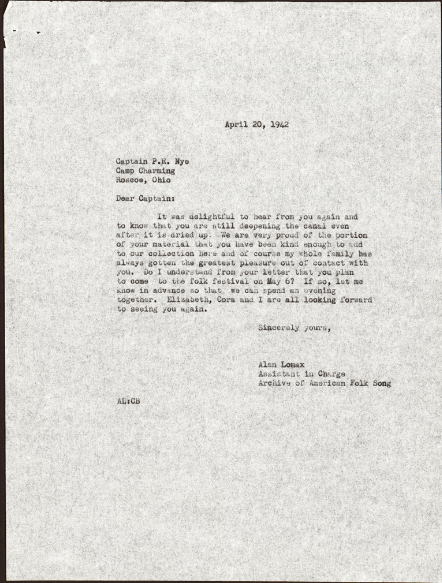

Photo credit: Jim Herrington