The cultural contrasts between Kaia Kater — the singing, Canadian, clawhammer banjo player of Afro-Caribbean descent — and Nefesh Mountain — a northeastern, husband-and-wife bluegrass duo made up of Jewish musicians Eric Lindberg and Doni Zasloff — are immediately obvious. But once you get them all on the phone together and begin to wade into the favorite topic of virtually every artist — music-makers they admire — commonalities quickly emerge.

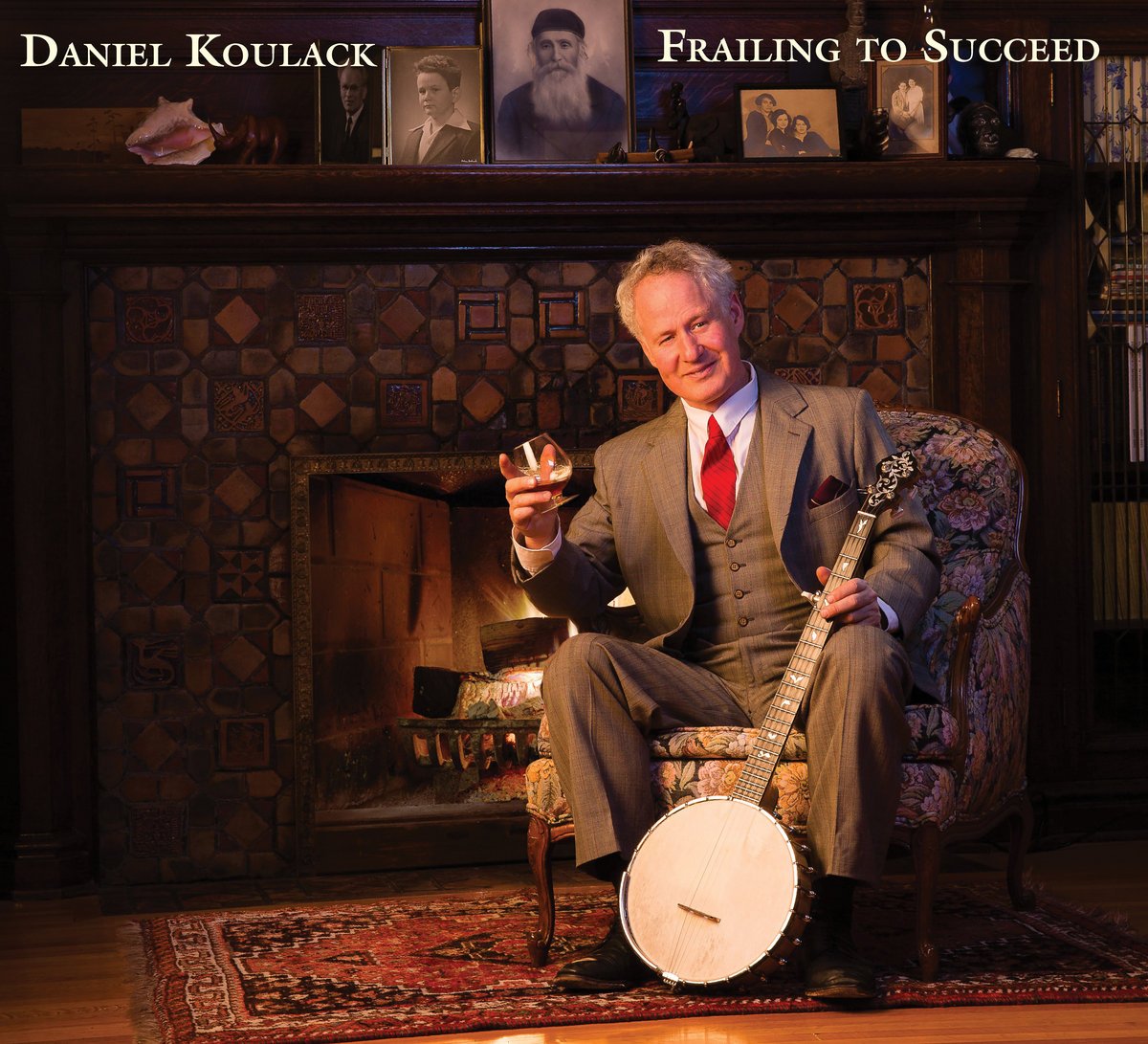

For starters, Kater and Lindberg, who also plays banjo, share a deep admiration for the musical curiosity of Béla Fleck. Kater was captivated by watching Fleck mix it up with his peers on the Banjo Masters stage at Grey Fox, hold his own with Questlove during a one-of-a-kind live jam, and retrace the banjo’s roots to West Africa in the documentary Throw Down Your Heart, while Lindberg has closely followed Fleck’s virtuosic pivots from progressive bluegrass to jazz fusion, classical, and a dizzying array of other stylistic territory. Fleck could easily “coast on how well he’s doing,” Kater marveled, “but I feel like he’s always into new things and discovering different parts of the instrument or its history.” “That, for me, has broken down any mental barriers that I’ve had,” Lindberg concured, “and maybe in some ways has helped me say, ‘It’s okay to do this,’ and kinda be fearless in it.”

They bonded, too, over their encounters with upright bassist Mark Schatz, who played on Nefesh Mountain’s recently released self-titled debut. “Did Mark show you any of his hambone?” Kater wanted to know. “Oh yeah!” Zasloff enthused. “He clogged and hamboned on the record.”

Kater’s latest album, Nine Pin, also has a track featuring percussive dance. But that’s hardly the most significant similarity between her output and Nefesh’s. Both artists are incorporating their multi-faceted identities and voices into string band music in compelling ways, and they had plenty to say about what it takes to win over an audience when you're coming from an unexpected vantage point.

Doni and Eric, meet Kaia. Kaia, meet Doni and Eric. I presume you’re new to each other’s music.

Eric Lindberg: Nice to meet you.

Kaia Kater: I just checked you guys out. You sound amazing. I just love it.

EL: Thanks! You, too.

Doni Zasloff: Likewise.

Let’s start with your encounters with preconceived notions about bluegrass music — who makes it, who it’s for, what it sounds like. My understanding, Kaia, is that, at some point after you picked up the banjo, you came to recognize that women of color are not well-represented in bluegrass. How did that shape your decision about what direction to take your banjo playing?

KK: I started playing the banjo, I think, at a time when it wasn’t very popular, so I didn’t tell many people. I started when I was maybe 12. I grew up going to bluegrass festivals. Like, I went to Grey Fox for a long time. I mean, that was before even the Chocolate Drops [were well known]. I sort of thought that it was a white instrument, and I just really liked it, which is why I picked it up.

I distinctly remember the Chocolate Drops showcasing at Folk Alliance and, at that point, they were just a bunch of rag-tag college kids who met their mentor, Joe Thompson, and realized the importance of bringing Black string band music into the musical dialogue. So I was obviously very inspired by what they were doing. Over the last 10 years, I [found] Valerie June — she’s a Black artist in string band and old-time music — and Leyla McCalla, who plays string band music.

McCalla’s collaborated with the Chocolate Drops at times.

KK: Yeah. So I think in terms of Black women playing old-time string band music, there’s never been a better time. I feel like we have critical mass now, which is a funny thing to say, but it feels good.

For a long time, I didn’t really wanna bring race into my music. I didn’t really brand myself as any type of Black music. I had a lot of influences who were Black women … like Nina Simone and Lauryn Hill were great influences of mine. I’m still coming to terms with what it means to me. I was talking to Leyla about it: There’s this understanding that the music you play is largely for white audiences. My cousins, they listen to Fetty Wap. They don’t listen to Abigail Washburn or anything like that. So, at a young age, I knew that my musical interests were a little bit different. I think I’m still trying to find my place within that and who I want to be and what I want to say.

Doni and Eric, you’ve pointed out that bluegrass typically exists in non-Jewish contexts. And I would add that there’s often been a perceived connection between bluegrass and white, protestant, Christian gospel traditions, as seen in the repertoires of Ralph Stanley, Doyle Lawson, Ricky Skaggs, Dailey & Vincent, and others. What made pushing against that perception appealing?

DZ: I would just start by saying, because it’s always been a vehicle for spirituality, it felt almost natural. We loved this music always. From our background, it was like, “Of course it’s gonna make sense for this.” It’s always been that vehicle in a lot of ways.

EL: I’ve loved everyone you just mentioned deeply since I was a kid, especiall Ricky Skaggs & the Kentucky Thunder Band and Ralph Stanley. If you’re going to put genres on it — which we all kind of hate using genres these days, because it’s all so cross-cultural — it was never religious music, per se. To me, it was just American music, but it always had this Christian undertone, which is not a bad thing in the slightest. But it just wasn’t one that I connected to in Brooklyn growing up. So it was just a little inward struggle. I felt so powerfully connected to my American heritage through bluegrass and old-time.

Our band and our music is very much by accident. We both are huge bluegrass fans, and when we were writing our music, this is what came out. It wasn’t like a purposeful endeavor to try to go out and blend stuff. As an artist, it really makes me feel good to try to follow my truth. And Kaia, we have some common ground here, where it’s not the norm; it’s not what people would think.

We’re on the road now. Whenever we’re traveling in airports — this just happened, like, two days ago: Someone came up to me and saw a banjo and said, “What do you do?” “Oh, we play bluegrass.” “What kind of bluegrass?” “We play Jewish bluegrass.” And then there’s a roar of laughter.

DZ: They can’t control it. They laugh.

EL: Like it’s a joke. Of course, you’ve gotta kinda look at it like that. Mel Brooks kind of set a tone for Jews being funny in the Old West and stuff like that.

DZ: But that’s not what we’re doing at all. It’s very soulful and it’s very authentic. I would say a preconceived notion is definitely something we face. But the minute people hear us and see where we’re coming from — and it’s this really authentic and spiritual place — they get it. But it does take a little bit of laughter and, “Wait. You’re doing what?”

You’ve pointed out an overlap between the instrumentation of bluegrass and Klezmer music.

EL: Yeah. Obviously, all over the world, the violin is played pretty commonly, especially in Klezmer. You have guys like Andy Statman, who can do the cross-pollination of taking a mandolin and playing Bill Monroe tunes and also play in a Klezmer context. Beyond the instrumentation, the overall feeling and drive of bluegrass, like a slight bit ahead of the beat, [is shared by] bluegrass and Klezmer. The same thing that makes Jews get up and dance the Hora [makes people] dance in the round to old-time fiddle tunes.

DZ: We actually experience that when we do these concerts. A lot of the audiences may not have had experience with bluegrass, some of the Jewish audiences. And the minute we start playing this music — there’s a Hebrew word called “ruach” which means spirit, and that spirit is in Klezmer that a lot of the Jewish community has felt — and they absolutely feel it the minute the bluegrass starts.

You’ve all made conscious choices about how you want to present yourselves as musicians, how you want to frame what you’re doing. Kaia, you straddle trad performer and singer/songwriter territory. Why is it important to you to do both, and emphasize that you do both?

KK: I think it comes with what Eric was saying about genres and how sometimes it is easy to get stuck in a genre. I think you can be and do whatever you wanna do. But for obvious reasons — for marketing reasons — people tend to categorize. You were talking about people asking you in the airport, "What do you do?" You get that question so often, and it’s a frustrating question.

I’ve always been drawn to the lyrical side of things, and I think it’s what keeps it interesting for me. It’s a way that I feel like I can grow. It’s been a little bit challenging to [step forward] more as a songwriter, because my first album was very heavy on the trad stuff. [For Nine Pin] I wrote a song called “Rising Down,” which was about the Black Lives Matter movement, and I had a little bit of apprehension: “How are people gonna take this?" Maybe people just want me to be a trad artist that plays West Virginia music or something. But it’s been really well received, which I’m really thankful for.

So this airport encounter that’s come up twice now … that’s a moment when you introduced yourselves explicitly as a Jewish bluegrass duo. What, to you, is the difference between placing the Jewish descriptor right out front like that and calling yourselves a bluegrass duo made up of two people who are Jewish?

EL: That’s a good question. I don’t present it that way. I don’t come out and say, “Jewish bluegrass.” Usually what I say is, “We play bluegrass.” We’ll show up in Denver and someone goes, “Oh, you’re in Denver. Are you playing [this or that venue]?” And we’re like, “No, we’re actually playing at a synagogue.” And then they go, “Huh?” And I go, “Well, we play Jewish bluegrass, and we’re leading a bluegrass Shabbat service tonight with a congregation, and then we have a big community-wide concert the next day.” And they’re still like, “So you’re not playing at Red Rocks?”

When Doni and I set out to make this record, I think we both felt really strongly that we wanted to make a bluegrass record from the perspective of two Jewish Americans.

DZ: One thing we’ve definitely come up against is the word “Jewgrass.” We don’t have a problem with it, but again it’s this question of, “What does Jewgrass imply?” So actually, I love saying “Jewish bluegrass.” I love to say it, because that’s what we’re doing. It’s just a matter of being authentic and owning who you are and celebrating your background, our background. I don’t know the best way to say it — I guess I’m just trying to be it. I’m not really sure of the language yet.

Kaia, your mother has been involved in organizing folk festivals for years, and you grew up attending them. I know you’ve also pursued formal studies in Appalachian music and, in fact, just completed your degree. Moving through those contexts, how have you made space for yourself?

KK: Doni, I really liked what you were saying about past all the labels “Is this Appalachian? Or is this bluegrass? What is it?” I feel the same. I think, at the end of the day, you just want people to hear your music for what it is. It can be many different things — things that, to a lot of people, seem contradictory or just not the norm.

Just speaking from a very recent experience, I spent four years in West Virginia going to school. There were a lot of experiences for me as a Black person going to West Virginia, which is not really Southern, but I think a lot of West Virginians think of themselves as aligning more with a Southern sort of mentality. There was so much richness there, and I learned an incredible amount, spending four years in a community and meeting people and going to square dances. You know, there are a lot of old timers that are pushing 80 who won’t be with us much longer, and them being willing to impart traditions on a Black Canadian, which I was very thankful for. There was a lot of beauty in moving to a region whose music I’d admired for such a long time.

If 70 or 75 percent of the time it was a wonderful experience, there was also that other part of the experience where I did encounter some racism, or I witnessed racism. I felt the racial divide very strongly, more so than in Canada. … I toured with a string band and a percussive dance team, clogging and flatfooting and Appalachian dance styles. I was with 15 other people from the school. It was myself and a Black tap dancer named Katharine Manor. We performed and then we were standing together at intermission. Nobody came up and talked to us. Like, nobody. And we would even try and talk to people. They weren’t really responding to us. We looked around and our friends, our dear friends, who are white, were getting such positive responses from some of these people. It didn’t cut us deeply, but the tension as palpable. At that point, I realized, “Yeah, you’re gonna perform for people that won’t get it, or that don’t understand your place in this type of music. That’s okay, because the majority will.”

When I’ve poured my heart and soul out for 45 minutes and I’m not getting any sort of response, at that point, you just have to do it for yourself. You have to understand that, some people’s hearts, you can’t change. Coming back from that experience, I think I’m much more Zen about the whole thing. I will try to change to change hearts where I can, but it’s not my problem if people aren’t open to what I do or what I have to say.

Eric and Doni, what does your performing life tend to look like? How often are you playing to an audience who shares a religious and cultural identity with you but is unfamiliar with bluegrass?

EL: Our shows are all over the map. We play for only-Jewish audiences sometimes, and for everybody. The gig changes from day to day.

One really bright note since we’ve launched the record and started to hear back from people [is] how many Jews love bluegrass. This is something I’m really proud to say I think people needed. It’s so gratifying to get an email from someone that says, “I’m a Jew who lives in Memphis, and I never thought this could be done.” Jewish audiences are really receptive to it, as well as non-Jewish audiences, who are really eager to learn about how Jews consider their spirituality. There are so many universal themes in what we write about. When we sing to non-Jewish audiences, there are so many themes that everyone can hold onto.

DZ: It does feel like an equalizer and a connector. We were just in Idaho and it was a mixed audience. I’m sure there were some Jews in the audience, there were some non — lots of different backgrounds. It’s like we get on the stage and just sing and be us. What was amazing was, by the end of the show, everybody’s up and dancing and celebrating together. It’s so beautiful, really.

You’re uniquely positioned to be able to play at a Shabbat service or a folk festival or other kinds of venues. What’s different about what you bring to the context of a Shabbat service, where people aren’t expecting to be passive members of a concert audience so much as participants?

EL: When we do a Shabbat service, it’s interesting because everyone in the Shabbat service generally knows the prayers that we’re singing — although we’ve written our own melodies and arrangements, the whole song behind these age-old Jewish prayers. But what we can lean on and make people aware of is the genre of bluegrass, spreading the love of the music, playing banjo, and having our fiddle player Gary and our bassist Tim — whose last name is Kaia, incidentally. It’s really thrilling to help people feel that lonesome Appalachian sound through connecting our worlds. We play in American Jewish synagogues and we’re playing American Jewish music.

You were saying, Kaia, that for a long time you weren’t sure if you wanted to bring race into your music, or how you would do it. You mentioned your song “Rising Down,” and there’s another on your new album called “Harlem’s Little Blackbird.” How did you move into telling stories in your songwriting that speak to experiences of people of color?

KK: Going back to what Eric and Doni were saying, I think most of us don’t go into trying to write an album or song by being like, “Oh, I’m gonna write a song about the Black experience in America.” You draw on your life or you feel inspired by something and it comes out. The songs that I put on the record were taken from moments of inspiration, rather than just trying to grind out a song because I’m Black and I should write a song about being Black.

I mentioned Katharine Manor, the tap dancer. Because we were the only two Black arts students at the school, I think the dance and music department decided to commission a piece from both of us, and also our professor. We were asked to get together every Wednesday night and try to come up with a piece about the Black experience [Laughs] which is, like, the opposite of what you want to do. It was like, “Great, we have to do this now, because someone said that we had to.” Our inspiration came from looking at the news and talking about what was happening. We ended up talking a lot about state violence and state racism. … Then, in December of 2014, Tamir Rice was shot in Cleveland, and I remember going into class the Wednesday after that happened and we were talking about it and we just broke down, because he was 12 years old. It was horrifying. … So I sat down and thought about what I was feeling, and then I came back with the lyric, “Your gun, it’s always at my temple.” I worked off of that and I wrote “Rising Down.” So we created a dance piece around that.

It’s been a very long process for me to work up the courage to talk about it, and it’s not something I take lightly. Actually, I’ve only presented the song live in my own shows about twice. I don’t know if you guys experience this, Eric and Doni, but when you start talking about things that are really close to your heart with an audience, it’s a very intimate bond that you create. And it is very hard as a performer to put that out into the world, into the audience, and let them catch you. You’re not doing something that’s part of the majority — it’s not Christian; it’s not white; it’s something that talks about hurt. I’m still trying to figure that out: How do you create that bond with your audiences?

EL: I love that image of a musical trust fall, kind of going out on a limb and just jumping off, hoping that the world is good enough to catch you. I think that what you’re talking about, Kaia, in racial issues and religious differences and all of these things that put up dividers between all of us, are hard things for people to deal with, but they’re also real things. You’re singing about real things, and we’re singing about real things. Your stuff sounds great. It feels like you. And our hope is that ours sounds like us. The best compliment that anyone could give us after a show is, “You really sound like you mean it.”

DZ: That goes a long way, being authentic. That’s all we’ve got, really.

Kaia, some years back you made a far more obscure recording called “Rappin’ Shady Grove,” a hip hop-style tweaking of a traditional number. Was that an early experiment with how you might bring disparate stylistic elements together?

KK: That was my very first EP recording. I think I was 17, and Drake was just coming out. Toronto was really proud. I was listening to a lot of Drake, and he was just telling his story. I just admired what he was doing. So I was thinking, “What’s my story?” I just decided to rap, but I think it was more like spoken word. I have listened to a lot of hip hop and rap, and that’s where I get a lot of my inspiration. So I just did it and put it out there and I felt like, “Okay, I’ve told my story in a way that feels authentic to me.” And I haven’t felt the need to do it again. But maybe in the future. Who knows?

EL: Within the last year, we’ve been playing a combination of songs live. It’s not on the record. A Nigun is a melody that you just kind of “Yaida dai.”

DZ: You repeat.

EL: [It’s that combined] with “Shady Grove.”

KK: That’s awesome.

DZ: Sort of mixed the two together.

EL: We kind of weave in and out of them. We put them in the same key. It’s an old Jewish melody. If you play it with Jewish instrumentation, then it might sound more Klezmer-y or maybe more Eastern European, but if you play it with clawhammer banjo, which is how I choose to play it, it had a really lonesome, haunting “Shady Grove” kind of sound.

Doni, I know you recorded “Singin’ Jewish Girl” — your version of Lily May Ledford’s “Banjo Pickin’ Girl” — which I first heard from Abigail Washburn. Was that a way of owning your musical space, placing yourself at the center of your musical story?

DZ: That’s exactly what I feel when I sing that song. Not to over-share, but you know, Eric and I fell in love writing this music together. So Eric actually wrote that song for me. When you meet somebody who really understands you and celebrates who you are, it’s just an amazing gift. Singing that song, not only do I feel I’m being authentic and being myself, but I feel this connection with him and this love of the music that we play.

I listened to some recordings that you made with your other group, the Mama Doni Band, and they’re very playful, funny, and kid-friendly. Bluegrass was one of many styles in the mix — along with reggae, disco, and lots of other stuff. You mentioned that you naturally went in a bluegrass direction with this songwriting. Have you reflected on how or why it became an outlet for more serious expression from you?

DZ: I think as a person, as an artist, and as a woman, you grow, you change, and you evolve. I’m continuing to find myself in my story and my life with my voice. I started out sharing Jewish culture with kids, and I wanted to share it, as you said, in a playful and fun way. That’s how it was expressed. I think as we wanted to go deeper with it, that’s where the bluegrass came in. When Eric and I came together was really when Nefesh Mountain came out. Again, it wasn’t planned. It’s just kind of what happened to us together. Bluegrass has the most pure and honest sound.

There are some fine pickers in the Northeast. Why was it important to you to come to Nashville and get A-list musicians like Rob Ickes, Scott Vestal, Sam Bush, and Mark Schatz?

EL: So much of what happened with the record, I feel like we’re still catching up to why it all happened the way that it did. It’s almost like we were being told by the universe what to do. Those guys are our heroes, so to play with Sam and Rob and Mark Schatz and Scott Vestal and our friend Gary, who played with us, was really the thrill of a lifetime, being northeastern Jews from the New York area who wanted to come down. I really wanted to make a bluegrass record that had the sound of a bluegrass record — not just people picking. If I could have Sam Bush play mandolin, that’s the sound of bluegrass. I mean there are a ton of people, now more than ever, who are playing in the New York area and New Jersey, but it really meant something to me to have some of these guys who, themselves, have redefined the genre. So it was important to me to have them help craft this sound and put a stamp on it. This is an American record; this is a Jewish record; this is something that has that sound, what they bring.

KK: Mark Schatz is awesome, and so is Sam Bush. Stellar lineup of musicians there. Nice work.

Kaia, how did you assemble your circle of collaborators?

KK: I have recorded only in Canada. Mostly because the Canadian government offers pretty generous grants to musicians — Canadian musicians — to record albums. You are eligible for more money if you record in Canada, which makes sense because they want to keep the economic growth within the country. You can work with a U.S. producer, but you have to fly them in.

I think what was important to me was to have some instruments on the record that were maybe not typically considered to be old-time instruments. I felt, because my lyrics are different and my songs are different, it would be fun to give them a different feel. So we brought in a trumpet and flugelhorn player, Caleb Hamilton, and a bass player, Brian Kobayakawa, and my producer Chris Bartos plays five-string fiddle and baritone electric guitar. I played banjo and a little bit of piano on the album, too. We also put in a little bit of Moog. I was interested in doing something a little different. I think, like Eric said, you want to keep the music exciting to you.

Is there any chance you all might be playing the same festival sometime this year?

KK: Are you guys going to IBMA?

DZ: Yep.

KK: Cool! Well there’s one.

EL: Are you playing?

KK: Yeah, I’ll be there.

EL: We should hang.

KK: Totally, totally.

Illustration by Abby McMillen. Photos courtesy of the artists.