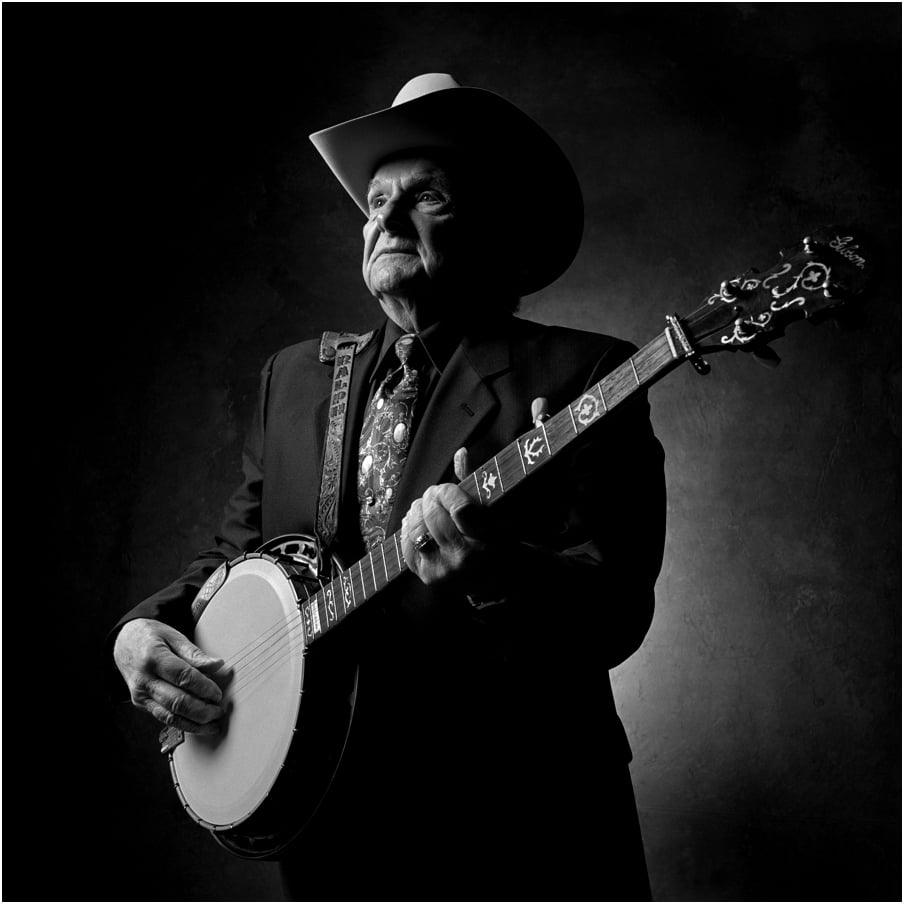

For some reason, North Carolina has long been the cradle of the Americana vanguard. In 1945, Earl Scruggs’ banjo sound created a rip-roaring hot rod of a genre called “bluegrass” (with Bill Monroe’s help, of course). In the ’60s, Doc Watson popularized a new guitar style while giving the folk revival a welcome dose of Southern authenticity. The “newgrass” boom of the 1970s owed a lot to a North Carolinian named Tony Rice, who became his era’s most important acoustic guitarist and, in turn, influenced a younger generation of fans, including Béla Fleck and Alison Krauss. Now fast forward to the 2010s and consider a Carolina string band called Balsam Range from a small mountain community in Haywood County, North Carolina.

If you approach Balsam Range with a discerning ear for key bluegrass ingredients, you won’t be disappointed. Great vocal harmony? Check. Killer instrumentalists? Check. Southern themes of home and hearth, with an accent to match? Check and check. But they also have something — a very important something — that an academic understanding of the genre tends to miss: They’re groovy. Balsam Range reminds us that bluegrass can be dancing music, hip-swinging music, backbeat music, as rhythmically hypnotic as all the plugged-in genres that formed in its wake. “It’s hillbilly soul!” says mandolin player Darren Nicholson. “It’s hillbilly funk and it’s hillbilly rock ‘n’ roll.” Not what you’d expect from the hills and hollers of Haywood County.

But Haywood County is just a stone’s throw from Asheville, after all, and maybe it’s not as culturally distant from that bohemian mecca as you’d think. Like so many hipster bourbon joints, whether in Asheville or Brooklyn, Balsam Range is playing with intriguing questions: How does Southern heritage fit into the present day? What can we learn from Appalachian traditions, and how can we carry them forward? Unlike these predictable bacon- and mason jar-themed bars, however, their approach to these questions shows some real originality, not to mention a deep knowledge of Southern music and a reverence for the richness of Appalachian culture as a whole — something they call Mountain Voodoo.

So y’all just put out Mountain Voodoo. I’ve been listening in the car. It’s a great record.

Yeah, it’s hot off the press. We’re really proud of it. I really feel like it’s the best thing we’ve ever done.

It’s clear right off the bat that you have your own style, your own sound. But I thought it was interesting that the description of Mountain Voodoo on your website mentions specific songs as if they’re different genres. It says there’s a “Tony Rice-style vocal song,” a gospel song, a honky-tonk tune, and others. How do you stay conscious of all those different styles and genres, but also just make something that sounds like Balsam Range?

Well, when you’re fan, when you truly love music, it’s like ice cream: You don’t like just one flavor of ice cream. So we can do a honky-tonk country song, we can do straight-ahead bluegrass, we can do a gospel tune, but the reality is that it’s always the five of us. You’ve got to get comfortable enough in your own skin to realize that, no matter what song you approach, it’s still us five.

I think that’s true. The whole thing sounds like one cohesive band.

Well, I hope so. We like traditional bluegrass and progressive bluegrass. We love the Americana stuff. We love playing to different crowds. We love playing to not just hippie crowds, but to any young crowd that has an open mind to music. And we try to express ourselves through different styles of music, but the reality is it’s going to sound like us. You could get George Jones to sing a Merle Haggard song, and it’ll be a Merle song, but he still sounds like George Jones! So, once you get comfortable doing your own thing — that’s the awesome part — it’s always going to sound like us.

So that’s what Balsam Range is doing, right? Focusing on having your own thing, not trying to be pigeonholed?

You’ll hear elements of all of our influences, of course. You’ll hear elements of Tony Rice or traditional stuff, but it’s about making the best music you can and being yourself. Bluegrass is like a curriculum. When you grow up playing bluegrass, it’s like learning your ABCs. You learn all that stuff, so it’s a part of you and it comes out sometimes, but that’s not what dictates who you are. You can show your roots, but you also have to do something that’s uniquely your own. Learning how … that’s a maturity thing. Once you realize how to blend that together, it can be a lot of fun.

That must be one of the hardest things to do in any style of music. You can learn the licks, you can learn other people’s songs, but how do you learn to sound like yourself?

I think that’s a problem with a lot of young musicians. Same as the problem with mainstream radio. They go with whatever is trending. You know, Frank Sinatra or Elvis Presley or the Beatles didn’t just go along with whatever was trending. They stayed true to what they did. George Jones, Bill Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs … they did their own thing. If you believe in it, then you keep hammering it out. It may take 20 years, it may take 50 years, but you have to stick with your thing.

It seems like some people treat bluegrass as a collection of licks that are supposed to be memorized and played in a certain way.

Well, the early generation really got it. Some of the newer bluegrass guys don’t — they’re trying to copy Tony Rice or J.D. Crowe. The first generation — Bill Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, Jim and Jesse, the Osborne Brothers, the Stanley Brothers — they all wanted to sound different. Then, if you’re doing your own thing, you’re not in competition with anybody else, even within your own genre. That’s what we’re trying to do in the modern day. We find songs that we like, a sound that is identifiable as us. And people like that.

People who really know bluegrass are aware of the history, about Monroe, Flatt and Scruggs, and the Stanley Brothers, like you’re saying. But when you’re playing mandolin, are you thinking, “This is a bit of what Bill would do?” Are you conscious of drawing from the history while you’re doing it?

There are elements of that, but, you know, I try to play what fits the song. If it’s a traditional-sounding song, I may put a Monroe twist on it. If it’s a modern, edgy kind of song, I may let the rock ‘n’ roll side of me come out. If you try to back up the singer and play to the song, you can never go wrong. If you get stuck in “I only play this style” or “I only play traditional bluegrass” or “I only play progressive bluegrass,” then you’re really limiting yourself. You’ve got to have an open mind.

So there shouldn’t be any problem combining Bill Monroe with rock ‘n’ roll energy?

He’s in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame! People forget this. He was an innovator. He was playing rock ‘n’ roll 20 years before Elvis. He influenced Chuck Berry. So he was part of the mountain music thing, the old timey fiddle music, but there was also a Black blues guitar player he grew up listening to named Arnold Shultz. That’s what makes bluegrass great. That’s what makes it uniquely American. Nothing was off limits to him.

People who are die-hard traditional Bill Monroe fans, they want to manipulate him into representing what their beliefs are. The reality is that he was open-minded. He’s the only guy in the Country Music Hall of Fame, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and the Bluegrass Hall of Fame. That was the cool thing about the old generation: Whether it was Frank Sinatra or the Beatles or Bill Monroe, they all realized they had to do their own thing. Now, when there’s a hit, they try to make 10 others that sound just like that hit. They conform to whatever is trending. Those guys didn’t give a damn about trending. They wanted to be unique.

You mentioned all the influences that combined to form bluegrass music in the early days. Taken all together, how would you sum up what bluegrass is? What is it that you love about it?

It’s soul music. It’s hillbilly soul music! It’s hillbilly funk and it’s hillbilly rock ‘n’ roll. The things that I love about a great funk band or a great rock band or a great country singer are the energy and the heart, when somebody really makes you feel something. When a great bluegrass band hits the stage and melts your face off and makes you say “WOW,” it isn’t just a bunch of guys busking with a washboard — it’s the real damn deal. It high-octane music with some real substance behind it. And when there’s substance there, that overtakes everything else. Great bluegrass gets down to the raw power of music.

I’ve heard other musicians say that, when they watch a killer funk band, they’re watching the bassist. Or when they see a tight rock band, even when there’s a great vocalist, they’re watching the drummer. When you’re listening to a great bluegrass band, what are you listening for?

It depends on the band. There are some bands I like because they’re not polished. It’s that raw thing that I love. There’s other bands I appreciate because it’s so clean, so polished. Our band tries to bridge the gap. The way I see it, whatever the band, if someone is truly good, you feel something when you hear the music.

My son is a huge Beatles fan. I mean obsessed. And that’s awesome. I love the Beatles. So, this Summer, we went on vacation and stopped off in Cleveland and took him to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Bill Monroe is in there and Hank Williams is in there, as well as a lot of Black blues musicians. You can see the roots of where it all comes from. Monroe is in there all over the place. If you listen to his early stuff — there’s a song called “Bluegrass Stomp” — you can hear it, man! It’s like Chuck Berry 20 years before Chuck Berry. It’s clearly rock ‘n’ roll. So I was thinking, you know, you can’t move forward unless you can look backward at the early guys.

You think something’s different now? You think we’ve lost some of that early spirit or energy or whatever it was?

Yeah, it’s seems too commercial now, too focused on repetition. If Miley Cyrus has a hit, they want the next 10 singers to have a hit that sounds just like her hit. They don’t realize that competition is what makes it great.

I love that we’re covering ground from Bill Monroe to the Beatles to Miley Cyrus.

There you go! You know, American music from the ’30s to the ’70s, I just don’t think we’re ever going to see a period of creativity like that again. The machine of selling stuff has now gotten away from that.

How old were you when you got into bluegrass?

I’ve got pictures of me on stage at 18 months old. I’ve been around it all my life. My dad played old-timey music, country music. The people who grew up in Western North Carolina, Eastern Kentucky, Tennessee, we’re very fortunate to be a part of that Appalachian music tradition. Mountain Voodoo — that’s not just the title of our record; it’s what happens when you’re exposed to it. There’s a magic in this music that gets passed down from generation to generation. That’s what we hope to carry on. I can’t remember not being into music and I can’t imagine doing anything else.

I started learning guitar, including a lot of old folk tunes, Doc Watson tunes, when I was about 10. I have other friends who discovered bluegrass when they were 25. And then there’s your story — on stage at 18 months. Is there something different between growing up on it and learning about it later? What do you think it gives you when you’re really reared on it from a baby’s age?

Well, we all end up getting to the same watering hole. But how you appreciate it or respect it, that’s a different thing. It becomes a part of your blood. It’s not just something you do when you get off work on Friday — “Oh, I think I’ll go see a show at the Orange Peel.” Those folks enjoy it, but we wake up every day thinking about it, getting the instrument out of the case, and working at getting better, rather than something you do for fun on the weekends. It’s in the fiber of our being, a part of us. For some folks, it’s an outlet, and they enjoy it on that level, but it’s a question of what level you take it to. It’s like throwing a baseball in the yard versus working hard enough to be Greg Maddux. We all love and appreciate it. The question is, “Is music a part of your life or is it your life?”

Do you have a particular memory of being moved by music as a child and realizing you wanted to pursue it?

I remember getting a Louvin Brothers record — Charlie and Ira Louvin, early country music — and I would sit in my room when I was 10 years old and listen to these records. They were singing about dying, about working in the cotton fields, losing loved ones — nothing that I’d experienced — but I would just sit there and cry. I was just emotionally overtaken. They were singing so good, they were playing so good, and they were being genuine about what they were singing. That’s why I can’t get fired up about what’s trending in L.A. or Nashville. It feels forced.

Y’all are from the mountains of North Carolina, and it seems like that’s a big part of who you are. I’d love for this interview to help explain to people who don’t know tons about bluegrass how to place Balsam Range within the genre. Does being from North Carolina, or from the mountains, affect the way you play bluegrass, the way you relate to the music?

Sure, what we play is Carolina music. Also it’s mountain music. Bill Monroe, of course, was from Kentucky, but it didn’t sound like bluegrass until Earl Scruggs came into the picture. He was from Shelby, North Carolina. And there is a magic that happens here in the mountains. That’s the voodoo. It grows here, you know? So when we make music, we’re paying homage to the people who came before us. There’s a sense of nostalgia, sure. But, from our perspective, we’re just keeping in mind all those who influenced us and just trying to keep the bar high.