Though singer/songwriter Chely Wright made her name on the country charts back in the ’90s, her new album’s quiet confidence showcases what is probably the truest side of her: a conscious and caring, creative and compassionate woman rooted in faith and family above all else. Produced by Joe Henry, I Am the Rain features 12 tunes written by Wright, along with one Bob Dylan cover that feels right at home in the set. It also continues the artistic recalibration Wright began with her 2010 Rodney Crowell-produced release, Lifted Off the Ground.

Congratulations on a hell of a decade you’re having. Can I just say that?

[Laughs] Yeah. It’s been pretty crazy. I’ve been really contemplative in the past few weeks as I’ve been doing some press about, “Gosh, what has happened in the past decade?” It’s been pretty action-packed.

Check my timeline. I was just putting it together. In 2010, you came out publicly, Like Me was published, Lifted Off the Ground was released, and the LikeMe Foundation was established.

Yeah.

In 2011, you got married … happy anniversary, by the way.

Thank you! Yep.

And the Wish Me Away documentary … which, kudos. That was so brave.

Thank you. I’m really happy with it.

Then 2013, the boys.

Yeah. Wait. Hold on. Got knocked up in 2012.

Okay. We’ll put that in. [Laughs]

Well, I mean, being a lesbian, it’s a little bit more than a back-seat of a Pontiac and tequila. It takes some getting done. [Laughs] So that’s important for the timeline.

Indeed. Then, 2014 was your huge Kickstarter campaign. So did you make the record last year or this year?

We made it in 2015 — 2014 was Kickstarter and my mother died in May. That really was a seminal moment in the process of the itch. You’re a creative person, you know. If you’re thinking about a piece you want to write, you write a lot of it in your head, I’m sure: “What am I going to say? What does it mean? What’s the point? What’s the art?” Then you get an itch when you know to sit down and start typing. My mom’s death in May of 2014 was the itch that caused me to go to my pile of songs and start taking inventory of what I had.

Got it. That Kickstarter campaign must’ve made you feel REALLY great. Did you write the songs and plot the record after that? It probably directed a lot of how you went about things, yeah?

I’ll answer both questions: Did it make me feel great, the Kickstarter? It made me feel things I didn’t know I needed to feel. When my managers and I discussed crowd-funding, at first, I was like, “That sounds like something other people do. I don’t really think I want to do that.” But Russell [Carter] was like, “You have to pay attention to the way history is changing. It’s not begging for money. It’s, essentially, a pre-sale.” He said, “More importantly, it re-engages you with your fans.”

I didn’t really hear that, when he said it. So, in my mind, when we kicked the whole thing off, my thinking was that a successful campaign would be to get funded. I quickly understood that the success of it, for me, was to reconnect with fans that had been following me for 20 years and new fans that I could connect with. More sentimentally, I was reminded that I didn’t lose all of my fans. I didn’t even lose half. Maybe I lost 30 percent of my fans because there were people saying, “You don’t know my name, but I love your records.” Or, “I saw you in Bagdad.” Or, “I saw you at the Nebraska State Fair in 1996.” It was emotional for me, in that regard.

But you probably picked up just as many from the documentary and all the other stuff, I would assume.

Here’s the thing about those new fans coming aboard: More people, in other demographics, became aware of me because I’m the new lesbian on the street, right? And they would go to my Facebook page and hit “Like,” I think, out of support for my coming out. But there’s a big chasm between somebody who doesn’t typically like what we think of as country music and their clicking “Like” on Facebook. They’re like, “I’m going to click ‘Like’ because I like what she did, but I’m not going to buy a country record.” So, a lot of those new people aware of who I am because of coming out — it doesn’t necessarily translate into record-buying, concert-going fans. In some cases it did, though. And that’s great. I love it.

And, to answer your second question: Did I write the songs before or after the Kickstarter? I think 70 percent of the songs that ended up on the record, I wrote before. And 30 percent after.

This record, it’s polished and pretty, but it’s not slick, I guess.

Ding, ding, ding! [Laughs]

[Laughs] Yeah, yeah. It continues to stake your ground in the more roughly hewn Americana world, which may be surprising to people who only know you from the way-back radio hits. What would be your message to those folks, in terms of getting them to keep listening, or re-listen, or start listening?

I love that you say that it continues to stake a claim there in the Americana world. It’s not slick. When you make a record with Joe Henry, if you want to make a slick record, you might as well put your guitar back in the case and leave.

And go on home.

[Laughs] And go on. Because Joe Henry … I mean, I learned a lot on my last record with Rodney Crowell, and I learned a lot with Joe. It was terrifying, frankly, the notion of working with Joe because I know what he does. And what he does is, he brings in everybody and demands that they bring their A-game for every second that they’re in there. There’s no going back and fixing. There’s not a “We’ll do this, then put a real guitar overdub on later and you can tidy up your vocals.” You have to get it when the band gets it. That’s scary for a person who’s made 20+ years of records that you can make them slick.

Punch-ins and vocal comps galore, right?

Yeah. Yeah. I had to unlearn a lot. I wanted to unlearn a lot of that stuff. You know when you go play golf and everyone’s watching you hit the ball? You don’t want to use your new grip, you just want to go back to that old one you know you can hit it with. But, if you want to change your game, you really have to go out there and swing with your new grip.

[Laughs] Ummm … a golf reference?!

[Laughs] I know, right? That’s how I equate it. There’s that temptation to use your old grip. But I went in fully trusting Joe and, frankly, fully trusting myself that this was worth being courageous. For that, I feel like we have a record that sounds like somebody hit record at a really good live show.

Working with Joe and some of my favorite players ever … plus your voice … other than the nerves, that’s a recipe for success, right there — that combination.

Well, one would hope. Our intention, with this record, was that it’s a narrative. It’s not meant to be listened to on your computer speakers while you’re emailing. You put your phone down. You put your favorite headphones on. You lie flat on the floor. You hit play. And you take in … I don’t even know how many minutes the record is. Do you know?

Let’s see … 13 x four-and-a-half …

I’ve got some long songs on there, friend.

Yeah, you have that fiver at the end, but you have some fours and three-and-a-halfs …

Alright. Yeah. Well, what we intended and hoped for people to do is put their favorite headphones on and hit play and follow along and absorb it. I’m guilty, even these days … I bought somebody’s record the other day and had the nerve to listen to it on my iPhone speaker. Halfway through the second song, I was like, “Shame on me! What am I thinking?!” [Laughs] Isn’t that awful?

Headphones on the floor … with maybe a little wine or … something … that’s my favorite way to listen to a record. It just is.

[Laughs] That’s how you do it! That’s what I want. If you glean anything from our discussion today, please pass along that that’s what I really want is for people to take a moment and absorb it in the spirit it was intended. Because Joe and I are really proud of it and we hope people find something in it that moves them.

How did those groovy little cameos come about with Emmy, Rodney, and the Milk Carton boys?

Well, first of all, Rodney … I call him Shep because he’s my shepherd and he has been for a long time. He and I co-wrote one song on the record called “At the Heart of Me.” It’s a song I had written and I brought Rodney in on. It was completely finished and we decided to let Joe join us. We never shared with him the actual music of it. We gave him the lyric, and he helped re-shape the lyric and the new melody. So Rodney was on the record, but it didn’t seem like that was a song to put him on.

But Joe and I had written a song called “Holy War” and Joe called me about five days after I got home from the sessions and said, “Hey, I called Rodney. I’m going to have him come in and see what he can render on ‘Holy War.’” I said, “Of course! Why not?! That makes sense.” What I love about Rodney on the record, it really does sound like … Rodney and I have done a lot of shows together and we end up around one microphone in the middle just singing … and it really sounds to me like a live take of a show.

What’s funny is that I get press releases all the time claiming “This record features Emmylou Harris,” “This one has Rodney Crowell,” and “This one has Milk Carton Kids.” You got the trifecta!

[Laughs] I did! I’m telling you: I’ve always been the luckiest person I know. I don’t know why, but I’m like Forrest Gump. I walk into these really great situations.

So Joe called me, again, about a week or so after I got back, and said, “’Pain’ is really raising its hand. It’s really standing up for itself, wanting to be seen. I think I’d really like to get somebody special.” We did some talking and who doesn’t agree that Emmylou Harris is just about as special as it gets. What made me so happy about her vocal is that she said, “I just want to match where you are. I just want to match the emotion of what you’re singing.” Hearing Emmy’s heartbreaking voice, her haunting voice, on a record of mine … not to mention a song I authored … I made up these lyrics and SHE’S SINGING THEM! What?! [Laughs]

[Laughs] Yep!

And it gets better when you know that, shortly after I moved to Nashville in 1989, I chased her around a Kroger at midnight one night. [Laughs] I came from a place where we didn’t have 24-hour grocery stores. When I got to Nashville, I worked at Opryland, and I got off my shift and needed groceries, so I went to Kroger. I’m buying my stuff and I see this beautiful woman that looks a lot like Emmylou Harris, so I start trailing her a little bit — like eight cart lengths behind her. Chased her down a couple of aisles and finally she turned around and said, “Yes. It’s me.”

[Laughs] Perfect.

[Laughs] I just nodded and turned around and ran the other way. So … 27 years later that she’s singing on a song I wrote … Isn’t that the American dream? Isn’t that what everyone wants?

I read in a Rolling Stone interview where you said, “Who doesn’t want to grow up to be Emmy or Loretta?”

Well, that’s true.

Did she pass along any advice to get you there?

Not directly. But one only has to watch what she’s done. That’s the perfect advice. When Rodney and I made Lifted Off the Ground, that was part of the discussion: I want to be a 55-year-old, 60-year-old woman sitting on a stool with 200 people showing up wherever I decide to play singing songs that I can believably sing. And say something. And feel good about saying something. She’s the gold standard — she and Loretta and Dolly. That’s as good as you get.

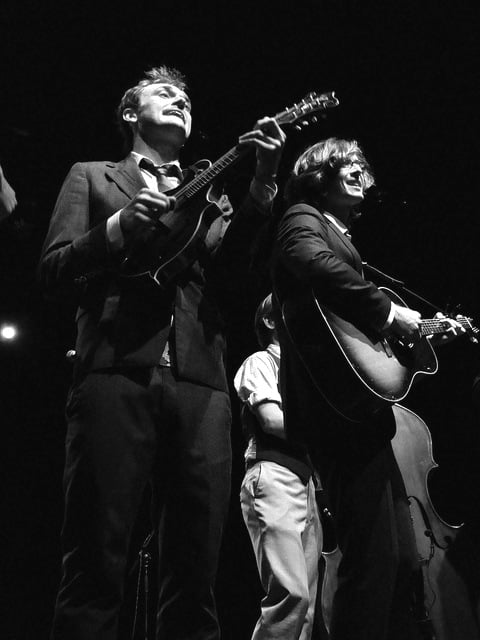

And then those crazy Milk Carton Kids … Joe Henry has a relationship with them. It was his idea to make the Bob Dylan song really jump off the page and I think they did magical work on it.

Speaking of … watch what I do here: Same Rolling Stone piece, you talked about how the pronouns in your songs wouldn’t suddenly go gay. But on the Dylan song — “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” — you sang it like he wrote it, which I always appreciate. I hate it when singers flip it so they don’t come off as … whatever. The beauty of storytelling is setting yourself aside and allowing space for listeners to insert themselves into the story. Is that your thinking, too?

First of all, I just love the craft in that sentence. That was really beautiful, a really great couple of sentences that you just spoke there. [Laughs] That is, I think, the beauty of storytelling. If you listen to my last record, there’s nothing on there, except for the song “Like Me,” where it’s clear I’m talking about a woman with whom I’m having a relationship. It’s not clear, in the other songs, if I’m singing as a straight woman or a gay woman. For this record, I’m singing a song called “Mexico” and I’m not singing as me. I’m the waitress in the song.

But, as far as the Bob Dylan song, I didn’t want to change it … for a couple of reasons. Bob Dylan is perfect and how dare I alter anything. But I really loved … it’s so intimate and it’s so truthful for me to say, “If only she was lying next to me, I could lie in my bed once again.” To me, it would’ve felt too cheeky to change it.

It’s interesting, though, isn’t it? Like, Patty Griffin, her pronouns are all over the place and nobody ever brings anything up. But as soon as you or Brandy Clark sing something either way …

The thing about Patty Griffin — which, by the way, when I say her name, I sign the cross on my chest — she was never part of the commercial machine that would dare question something so trivial and small. … Patty is the ultimate … she is the character singer. We don’t know anything about Patty Griffin, the person, really.

No. And she won’t give it up in an interview, either. I can tell you that.

She won’t. That, to me, is just a different way of approaching her art. And, boy, it’s paying dividends for her listeners. We love it, right?

We really do. Talk to me about the difference in feeling you get from impacting someone’s life with your activism or your charitable endeavors versus your music.

That’s another … you’re on fire today!

Thank you!

Without a doubt, receiving a letter or speaking to somebody … I got a beautiful letter today from somebody in Washington state, a young person, that said my book saved their life and my film helped start a repair with their parents. There’s no comparison. That’s it. That’s the most gratifying, the most heart-warming, the most invigorating, humbling thing I can experience.

And you wouldn’t have that platform without the music, so they are really kind of inseparable, in a lot of ways.

That’s a great point. That’s a really great point. There was criticism, when I first came out. I remember seeing a few things. People’s rants about “She did this for attention” … which is ridiculous. I don’t know of anyone … that’s obviously spoken from a straight person. Or people who say, “I didn’t get an award for coming out as straight!”

Yeah, because did their family disown them for that? Did they contemplate suicide for that? Really, guys?!

Right. Yes. When people have been critical, and I don’t hear it so much anymore, but when people have been critical about my coming out publicly the way I did, my feeling is, “I’ll tell you what: You go move to a city, from a podunk Kansas town, with thousands of other people who want the job that you want. You get the publishing deal. You get the record deal. You go on all the radio tours. You do all it takes and work with the record label and bust your tail end and you get a couple of hit records and then you decide what you’re going to do with that.”

I made my decision and it was the best thing I ever did — not just to come out, but to come out the way that I did. I look at my life now … my wife and I are celebrating five years and I just know I wouldn’t be alive, had I stayed in the closet. So, life is good.

For more on country singers going Americana, read Kelly’s interview with Wynonna Judd.