From the Bluegrass Situation and WMOT Roots Radio, it’s Hangin’ & Sangin’ with your host, BGS editor Kelly McCartney. Every week Hangin’ & Sangin’ offers up casual conversation and acoustic performances by some of your favorite roots artists. From bluegrass to folk, country, blues, and Americana, we stand at the intersection of modern roots music and old time traditions bringing you roots culture — redefined.

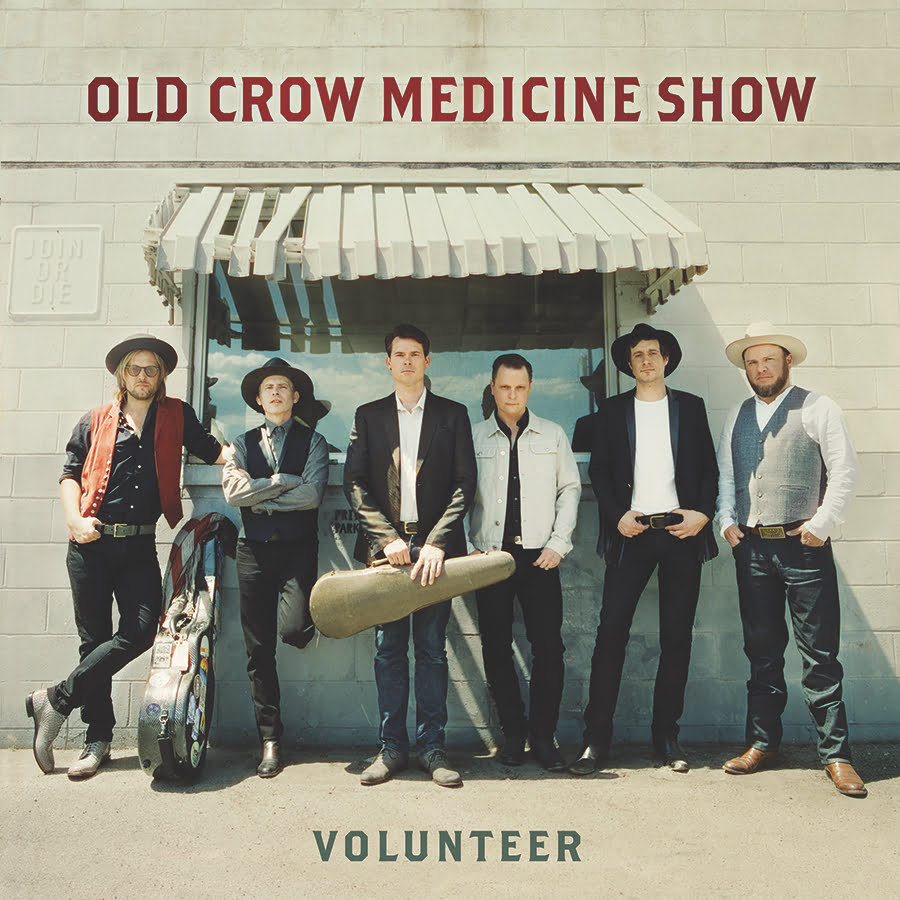

With me today at Hillbilly Central, Chance McCoy! So Chance McCoy, part of Old Crow Medicine Show, and more!

And more! So much more.

So let’s do a little Chance McCoy 101, background thing because you don’t have a website for people to go and find out about you so I think we need to teach the people.

Yes, I’m the 21st century George Harrison of Old Crow.

Alright, let’s go with that.

The Quiet Crow. [Laughs]

Yeah, okay, I’ll believe that. [Laughs] So you grew up in West Virginia, playing in punk and rock bands, yeah, a little bit?

Yeah, a little bit.

In your youth.

A little bit. The first band that I was in was called the Speakeasy Boys, and that was more just an excuse to get drunk and run a speakeasy than it was to be a band. But I did learn some music in there.

Right. And they were sort of old-time without knowing they were old-time? Kind of like the punk version of old-time?

Yeah, we didn’t know what old-time music was, actually. We didn’t know what bluegrass was, and we had heard the term “old-time.” And we were playing some old-time music. We had a washtub bass player. We were playing “Soldier’s Joy” and things like that. But it took me, like, a year of being in that band for somebody to finally tell me what old-time music was. [Laughs] We kept asking around, “What is old-time music?” and nobody could tell me!

So yeah, it was amazing! We basically ran a bar out of a basement of a friend’s house and, every Sunday, a friend of ours would go down to the Potomac River and fish out a bunch of catfish and we’d fry them on a barrel, and about 200-300 kids from the local college would show up and we’d play music. It was a ball.

That’s awesome!

So that was my experience learning folk music and bluegrass and old-time, and then I started performing in folk clubs and I was like, “Why is everybody sitting down and listening? This isn’t what you do, here’s a beer! Go ahead and dance, just start dancing!”

What do you think it was about that kind of music, or maybe it was how you guys were doing it, or maybe it was the beer and catfish, but what was the appeal to those college kids?

Um, I think the appeal was that we created a scene. Our bumper sticker read, “We’re not a band. We’re a party.” [Laughs] That was the appeal!

Your life motto ever since!

Yeah, I think that works for a lot of acts. Sometimes it’s not about the music; it’s about the event — creating a party. So that was very much what the draw was in that band.

And then once you got into the more “proper” old-time and folk scene, it was a whole other vibe.

It was a whole other vibe, yeah. It was great because, growing up in West Virginia, I’d actually never heard folk music, because it was pretty rare. I mean, it still is. I didn’t know where to look. I didn’t have any connections to it. So, when I finally discovered folk music in West Virginia, I was in my early 20s, and I realized that there was incredible depth, this well of music that went so much deeper than just the surface level “Soldier’s Joy” and all that kind of stuff — “Pig in a Pen.” And that’s where I really started to fall in love with old-time music, especially. And I was lucky enough to study and apprentice with master musicians form West Virginia, so that’s where it started to change for me. And then I took all that and went out and tried to perform it and that’s when I realized … [Laughs]

That’s when you ran into all the folks who were … the “that ain’t bluegrass” folks.

Like, “Well, actually …” [Laughs]

…

So you were just living out in a cabin and teaching fiddle at Augusta Heritage Center when you got the “Hey, come try out for our little string band, Old Crow Medicine Show” call.

Yeah, I got a cold call! Yeah the little string band that you know, we have the song “Wagon Wheel.” Nobody’s heard it.

Nope! What was it like stepping into that band with them having been a band for so long, even though they took a few years off, sort of regrouping?

It was really hard because I had to figure out how to join this band, like you said, that had already been a huge band that had been really successful, and I had to figure out how to enter the band and not make it seem like I was trying to replace Willie Watson or what he did. And that was always something that was really a sensitive issue where we all wanted to integrate me into the band in a new way where it didn’t feel like, “Oh, Old Crow’s back, but now this guy’s replaced this other guy.”

So there was this intentional shift in the band, and I tried to take sort of a back seat role and a more supportive role in that band, and not try to, you know, try to get myself out there and play a leading role in the band. And, in doing that, I was able to really support them to go in directions that they hadn’t gone before, and I was integral to the creative process and helping write the songs and record the records and doing all that, but I was sort of the behind-the-scenes guy, where I was just kind of trying to make Old Crow great again, and lift them off.

Because, when I met them and they went on that tour that I joined them on, when they reunited, they had kind of come out of a broken place with having lost Willie, and then being like, “Is anyone gonna like the band anymore? Are we gonna be able to do it? Is it gonna be any good?” So it was a real fragile situation that I came into, so I really tried to come in and just support them as musicians and help them realize their vision for what the band was gonna be moving forward.

And clearly that worked, or it was just a coincidence that you joined the band to play on Remedy and oh, it wins a Grammy, the first Grammy for a record.

[Laughs] I like to say I have the Midas touch. Any project I join wins a Grammy.

If anybody needs a fiddle player/banjo player/guitarist/carpenter …

I can build it. I can play it.

And you can win a Grammy.

[Laughs] Yeah, it was an amazing rise to success, especially coming from where I had been before I got the call. I had kind of sunk into poverty in Appalachia and it was rough times, for sure. I was just scraping by, barely, when Ketch [Secor] called me. So that was a good call to get.

…

You recently did some solo shows here in Nashville. So is that still a lingering ambition in your mind, are there projects coming?

It is! Yes, there is a project coming. I’m gonna be going into the studio in a couple weeks here, after I finish building it. [Laughs] And laying down my next record, which is gonna be called The Electric Crow. It’s kind of the next creative project where I wanna use all the different elements, all the different kinds of music that I play, and kind of bring that through my own creative focus and hone in something completely new. So, yes, that is on the way!

Watch all the episodes on YouTube, or download and subscribe to the Hangin’ & Sangin’ podcast and other BGS programs every week via iTunes, Spotify, Podbean, or your favorite podcast platform.