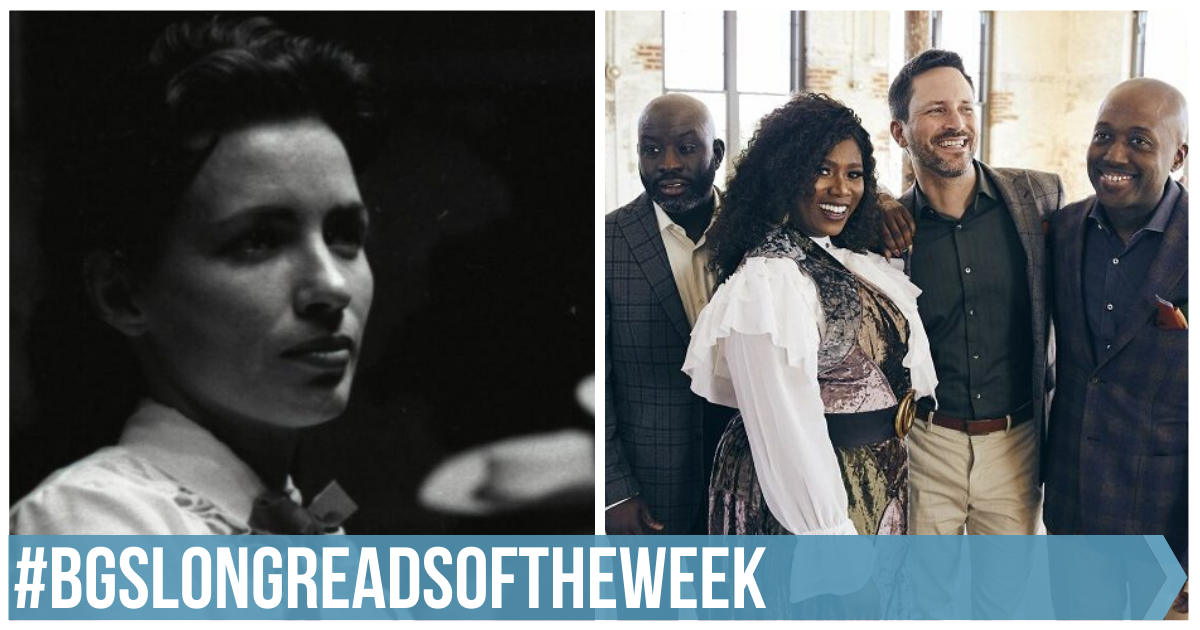

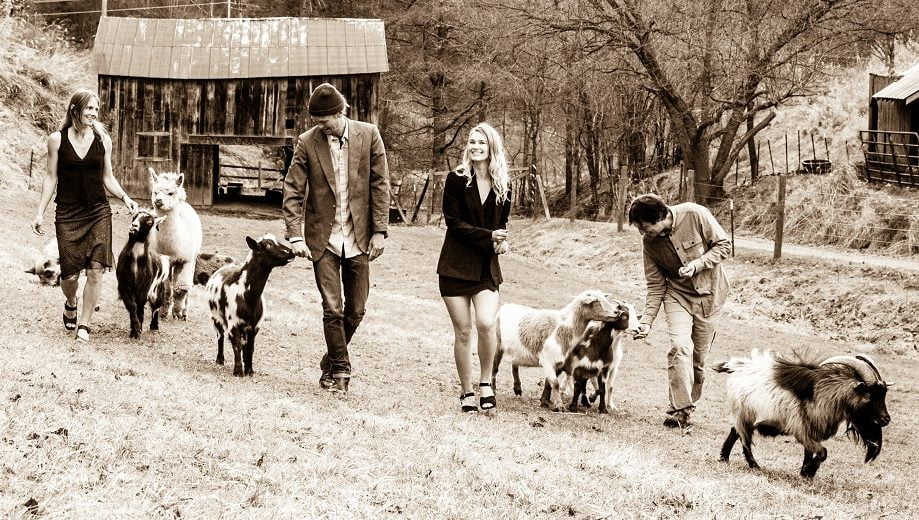

On an unseasonably cool summer afternoon in Los Angeles, something very interesting happens as Cary Ann Hearst and Michael Trent chat with a third person at a cafe patio table, though it takes a few minutes to unfold.

The topic, at first, is how much real life is in the songs Hearst and Trent make as the sweetly rackety, Charleston, South Carolina-based duo Shovels & Rope. Does it reflect their decade’s worth of experiences as a married couple and, now, their experiences with two small kids? The material, after all, gets kind of dark at some turns.

“Yes and no,” Trent says. “I mean, we’ve always kind of been character writers. That’s just the type of writing that’s been interesting to us. And also, we’re, you know, generally happy people. We don’t need the suffering to…”

“I hate suffering,” Hearst interjects cheerfully.

“Some people feel they need to experience firsthand some kind of suffering to make art,” Trent continues. “And I’ve never really subscribed to that. We just make up the world and make up the character thing and write about it.”

Then, as it does, the subject turns to murder ballads. They’ve done a few in the course of their time together. There’s “Evil,” a song they wrote on the 2014 album Swimmin’ Time. And their new album By Blood features “Pretty Polly,” their reinterpretation of the staple of the British-Appalachian folk canon.

“We’ve got a song like ‘Evil,’ right?” Trent says. “So we didn’t have two kids at the time. And we’ve definitely never abused them. And Cary’s still alive. So that’s obviously just a made-up story.”

“And ‘Pretty Polly,’” Hearst notes. “We’ve never gotten anyone pregnant and killed her by the river.”

But then things take an intriguing turn. They get talking about the whole nature of murder ballads, the enduring place of them in music and culture. Hearst wonders about the clearly misogynistic violence of the form still having a place in our supposedly enlightened culture: “Why is it OK in this day and age that the murder ballad is this weird, sacred musical thing that we aren’t like, ‘Cancel! Hashtag cancel’?”

As they discuss this, though, they focus on each other. They lock eyes, talk only to each other, and it’s as if the rest of the world has gone away. He defends the form, noting the relationship to and appeal of crime drama and horror stories.

“You’re right,” she concedes. “I never thought of it that way. It just feels closer to home and personal because these are songs. Maybe it’s like, ‘What are you singing this song for? Did you do that? Is that what you think?’”

Trent shrugs. “I don’t know.”

“Just occurred to me that you might have the answer,” Hearst says.

“Oh, like I’ve got some dark secrets?” Trent wonders.

And so it goes for a few minutes.

If you’ve seen them in concert, you’ve seen this. In a small L.A. club the night before this conversation, it seemed they spent the first several songs hardly looking at the audience at all, just staring into each other’s eyes as they performed before later turning things more outward.

They laugh at this notion. The truth is, they say, on stage that behavior tends to be more pragmatic than romantic.

“I think we were trying to figure out what this was,” Trent says. “We check in with each other a lot. This was a bit of a weird show in a weird place. And we also do a lot of musical communication on stage, just checking in with each other. A lot of people mistake that for us, like, lovingly looking at each other. And it’s really like, ‘Oh. I know you missed your cue…’”

“‘Are you going to miss it again?’” Hearst interjects.

Their 2008 debut, self-titled album, they say, preceded them becoming a real item in life and music. Since that time, they’ve figured out the ever-shifting dance of the personal vs. the professional, art vs. life. They’ve figured out how to put them together when necessary and keep them apart when demanded. After making 2016’s Little Seeds as new parents, they added a buffer between work and family space.

“After Little Seeds, when our first kid was born, we were like, ‘This is insane,’” Trent says. “We need a place that’s not in the house. So we just built a utilitarian building in the backyard. Now we have a place that we can separate the work by at least a few feet.”

“Being parents for the first time, everything was insane,” Hearst says. “We would have somebody come over to hold the baby while we went upstairs to record, and you can hear it, the baby’s screaming downstairs. It’s just so much better now. It’s saved everything. It felt like it was a smart move to make.”

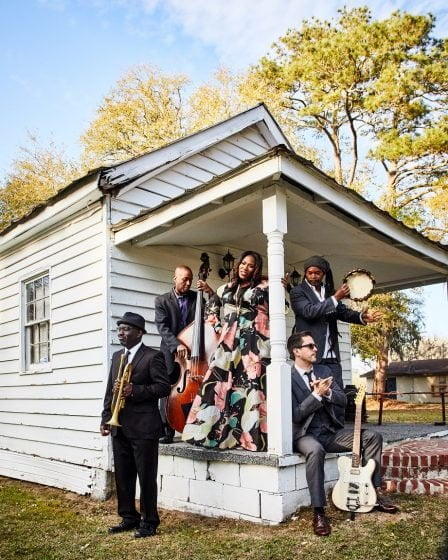

And, touring now for the first time with two kids, they’re spending part of the summer as the opening act on fairly big shows with Tedeschi Trucks Band and Blackberry Smoke.

“First of three acts at big sheds,” Hearst says. “Great catering! On early, like around 7.”

“We’ll be able to put our kids to bed at night and then have our jammies on by 8:30,” Trent adds.

Still, they allow, there are some deeply personal things that, pardon the expression, bled through on By Blood. The opening song, “I’m Coming Out,” with its very specific birth references and their second child now having been born a mere five months ago? That’s just the start.

“There’s some pretty personal things on this record for sure,” Trent says. “Like ‘Carry Me Home.’ Is it a pretty confessional song? Yeah, that’s true, like leaning on the other person.”

And there’s “The Wire,” which opens with the line, “I’ve been a disappointment at times.”

“‘The Wire’ is very much about how nobody is the perfect partner that you want to be,” Hearst says. “If you’re accountable, and they want accounts, good enough. This whole record is people who are jussssst good enough, but want to be a little bit better.”

Then there’s the title song, about the light and shadows of being in each other’s space all the time, of never having to be alone but never getting to be alone. Not only does the song close the album, but they put the lyrics of it in clear, can’t-miss type right on the front cover. That, and the whole album, per Hearst, serves as something of a marker in their lives and career.

“I think that we have many years of records in us,” she says. “But if this were to be the last stand, you know, of our creative output, there is a kind of timestamp with By Blood. We’re like this little baby that’s grown from making our first homemade record in the most rudimentary situation, and we got a little better at our instruments, a little better at record-making.”

But it goes deeper than that.

“I feel like we’ve become adults on records,” she continues. “Definitely we got adulted by Little Seeds. I mean, that time period after Swimmin’ Time and before Little Seeds was like, ‘Oh, you mean we’re growing older? We’re not gonna live forever? And our parents are getting old and babies are coming? Oh my God, we have to have life insurance and how come we can’t be just like, you know, freewheeling children for the rest of our lives?’ It kind of turned inward and now we’re kind of on the other side looking out and moving forward.”

Photo credit: Curtis Millard