Tim Stafford could be renowned for any one of his many contributions to bluegrass music over his prolific career, his talents as a musician and writer having been showcased in so many of its important creations. He is perhaps most well-known as a founding member of Blue Highway, one of the most influential and decorated bands in bluegrass. Prior to that, he formed Dusty Miller in the late 1980s, and Alison Krauss hired him in 1990 as part of her band, Union Station, with whom he recorded the Grammy-winning album, Every Time You Say Goodbye.

Stafford is also an accomplished author. In 2010 with Caroline Wright, Stafford issued Still Inside: The Tony Rice Story, the authorized biography of the flatpicking icon and Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame member. As a songwriter, Tim has placed more than 250 cuts and was named IBMA’s Songwriter of the Year in 2014 and 2017. He notably co-wrote IBMA’s 2008 Song of the Year, Blue Highway’s “Through the Window of a Train,” with Steve Gulley. Tim and Steve were frequent collaborators and released a duo album in 2010 called Dogwood. Ten years later, they created another album of co-written material, but Gulley passed away suddenly from cancer soon after it was completed, making the title, Still Here, all the more meaningful.

BGS: How does it feel to release this record? With Steve’s unexpected passing I imagine it must be a more heavy feeling than a typical record release.

TS: Yeah, I’m really glad it’s finally out. Steve was really looking forward to this record coming out. We were both excited about the songs and it ended up being his last recording, which was hard on all of us. And now it’s part of his legacy. After Steve passed, I talked to the label about maybe coming up with a different title besides Still Here, but we decided it was a very appropriate title because his music is still here. He would have been proud of it. I know that for sure.

How long had you known Steve?

I didn’t know him when I was younger, although he was around and playing. He was mainly playing up at Renfro Valley in Kentucky and he didn’t travel much until he joined Doyle Lawson & Quicksilver which would have been in the late ‘90s or around 2000. I was playing a festival somewhere with Blue Highway and he came up to the record table and we started talking like we’d known each other forever because we knew a lot of the same people. We just hit it off. He was the one that first suggested we write and it was either the first or second time we got together we wrote four songs in one day. And all four of them got cut. I felt like at that point we had something special. We seemed to have a wavelength that we could touch off of each other. That’s really rare. You don’t get that with a lot of people.

The subject matter in the songs on this record seems very personal, and often about people you know. I would imagine that it’s sort of therapeutic, maybe in the same way that journaling might be, to write about personal things like that. Is that how you feel about it?

That’s a good way to put it and I did used to journal. Some of them, like “Back When It Was Easy,” are just about general topics that we know about. Whereas “Long Way Around the Mountain” and “She Threw Herself Away” are about things that actually happened that we chronicled about friends. And sometimes they are big stories that you just can’t stay away from. “She Comes Back to Me When We Sing” is a story we’d both seen on Facebook about this guy’s mother who was in advanced stages of Alzheimer’s and didn’t know anybody until she sang with her son. And when that happened, she remembered all the words and she could remember everything. We thought that was a really inspirational story and deserved to be a song.

You’ve been writing for so long that it seems like you’ve been able to build the skill of telling a story through song, rather than narrating a timeline to music.

Yes, that’s where it’s at. That’s where the craft comes in that you only develop by doing it. I really didn’t know how to write a song when I started. But you learn little things along the way through trial and error. It’s like anything but it’s really difficult to learn how to do something like write a song out of a book — although I have a whole collection of them here. I have lots of books about songwriting like Jimmy Webb’s Tunesmith and Sheila Davis’ The Craft of Lyric Writing which is really good. You can learn tips, but you’re not going to learn how to write from a book. So it’s a matter of doing it.

I don’t remember exactly where I heard it, but I think I remember Jimmy Webb talking about writing “Wichita Lineman” and him saying that it was fully fictitious. But that he felt like, as a songwriter, he should be able to write about people he didn’t know. That he should be able to understand people well enough to write a story that was convincing without it having to be true. I could be misremembering that, though.

You may not be. I think that there’s actually a book out about that song, “Wichita Lineman,” that I finished here last year and I believe you’re right and he’s right. I think that being able to tell a story about somebody you don’t know is important. There’s a song that I wrote really early on called “Midwestern Town” that Ronnie Bowman recorded. That song is totally fictional. I didn’t know anybody like the character in that song. But I’ve had a lot of people come up and say that they did know someone like that or that it could have been them and that song made a big difference to them. It was a comforting song. You’ve got to be able to get inside people’s heads and think the way that they would. You have to know what your character might do in any given scenario. I can’t remember all the times I’ve been co-writing and said, “What would this guy do?”

Have you written songs as long as you’ve been playing guitar? When did you started writing songs?

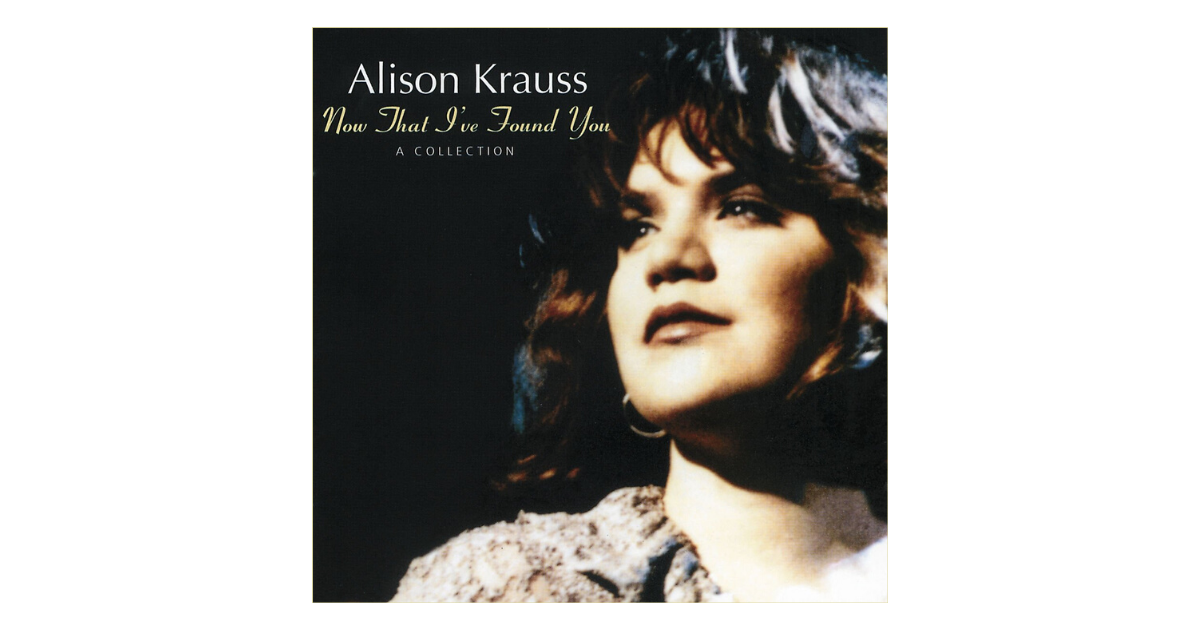

I guess I wrote all the way back when I first started playing guitar, but I wasn’t really serious about it. I had written some songs before I played with Alison in the early ‘90s and we actually recorded one of them, but it never came out which was my fault. She wanted to put an instrumental I’d written called “Canadian Bacon” on Every Time You Say Goodbye, but I talked her out of it. I told her we needed to record “Cluck Old Hen” because we were so psyched about Ron [Block] being in the band and his playing on that. And I don’t regret that though it probably would have meant more money.

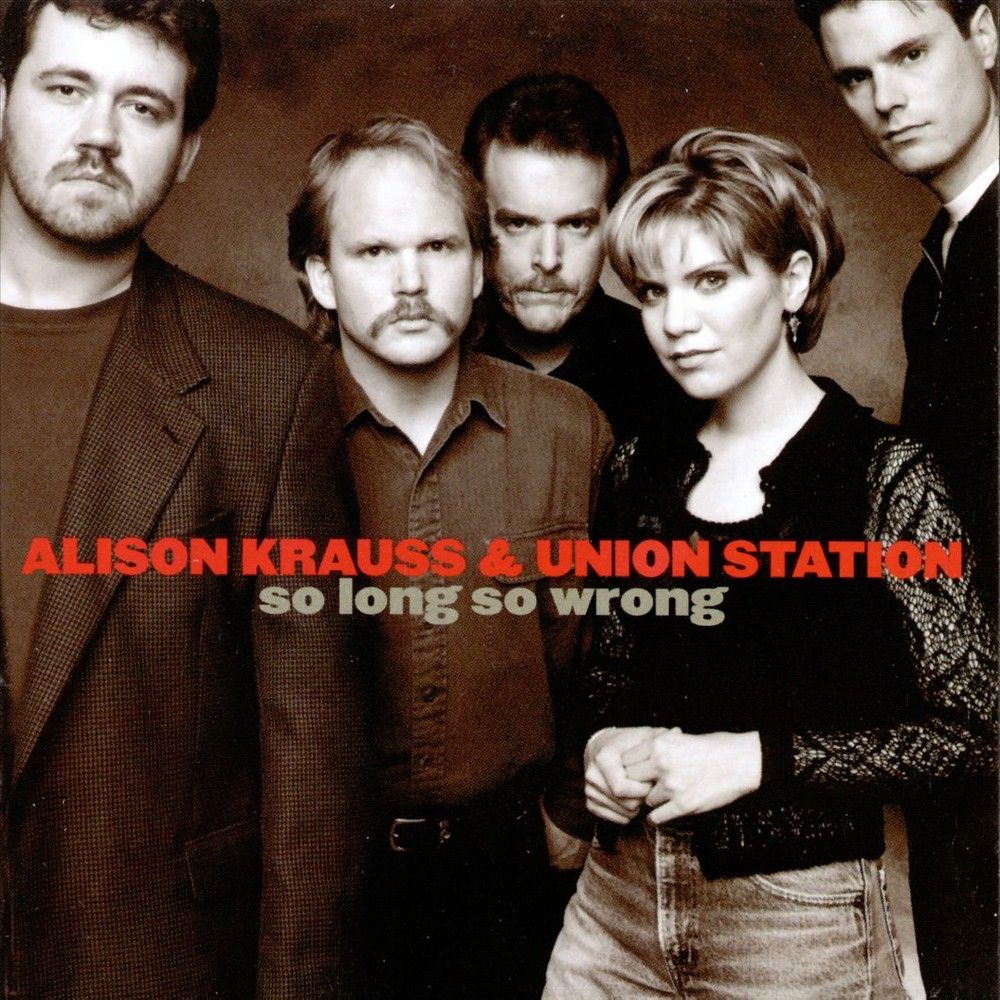

You were in Union Station from 1990 to ‘92, right? That was a very cool lineup of that band. How did you feel about it at the time?

I was blown away by it. I loved it and it was really cool that it worked out because the first time she talked to me about playing with her, it was back when I was in a group called The Boys in the Band. We played at SPBGMA and her band was there but her guitar player, Dave Denman, was leaving. She called me a few weeks after that and asked if I’d be interested. At that point, she had only recorded Too Late to Cry and I was really impressed with the songs, with John Pennell’s writing, and her singing. I had already committed to playing with a different group though so I had to decline.

About two or three years later I had started a group called Dusty Miller that she was a fan of. That band had Barry Bales and Adam Steffey in it. The three of us kind of grew up together playing music. We’re all from Kingsport, Tennessee. I actually gave Adam his first mandolin lesson, which is such a joke. [Laughs] Adam didn’t know anything about the instrument at all at the time. I tried to show him some stuff and I just kept thinking, “That guy’s never gonna get it.” And I barely knew how to play myself but I tried to show him “Bluegrass Breakdown” and he just couldn’t get it. He got with a different teacher after that and got real serious about it. The next time I saw him play, I was like, “What happened here?” [Laughs] It was like the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen in my life. I take absolutely no credit for that whatsoever.

Barry Bales was a student of James Alan Shelton. And James and I both taught at the Guitar Shop in Kingsport. That’s where I met Adam and gave him that lesson, and I met Barry down there, too. We all three ended up playing in The Boys in the Band. And then we started Dusty Miller. Alison liked that rhythm section so she offered the job to all three of us at the same time, and we took it. This was early 1990 and we played our first show in May — I think it was at the Station Inn. It was just incredible. We played some amazing places, but it was during the period of the band when we were all traveling in a van and staying in one hotel room.

I was playing with Alison when I met Tony Rice. We ended up playing a lot of shows together because he and Alison had the same agent and were on the same label. I never will forget the first time I really ever talked to Tony much. We were playing right before him at Winterhawk (which is now Grey Fox) and I broke a string on the last song we played. We got a standing ovation so I was backstage digging around, trying to find a string so we could do an encore. And Tony walks over with “the antique” and says, “Hey, man, here, play this.” I had a smile from ear-to-ear and Alison was smiling too.

What was it like getting to put that biography of Tony together? What led to that?

Well, a few years after that, after I left Union Station and started Blue Highway, I was still playing shows with Tony because Blue Highway had signed with Rounder, too. We were at a show with Tony and I said, “Man, have you ever thought about a biography?” And he said, “Well, actually, yeah, I have thought of that. But I’ll tell you what,” he said, “I think you’d be the ideal person to write it.” I said OK and started on it. That was about 2000 and it took 10 years to finish.

Three years into it, Caroline Wright came on board through Pam [Rice, Tony’s wife]. Caroline is a journalist and her mom was a member of the bluegrass community from New York state. Caroline lived in Hawaii at that time and had written a really well-done article about Tony in Listener magazine. I had started Tony’s book, but I was bogged down with it and wasn’t making a lot of progress and Pam suggested that Caroline come on board. We did four or five major, huge interviews with Tony that could have each been a book by themselves. And when we started transcribing them, we realized that Tony was so eloquent that we had to put it in Tony’s words. We couldn’t make it a narrative biography. That’s why it’s laid out the way it is. It’s chronological but in Tony’s words.

I’m really glad that we got to do it. Somebody would have done a book on him eventually, but I’m really glad that it came out before he left us. He’s one of those generational talents. I just don’t know that there’s going to be many people ever come along again who have an impact like that. He’s in the same league as Earl Scruggs, a top talent who created a language on the instrument.

So, it’s been a weird year, obviously. What have you been doing during this time?

I’ve been doing a lot of co-writing over Zoom. The other day I wrote my one-hundred-and-fourteenth song since the pandemic started.

Whoa!

Thomm Jutz and I’ve written 40 or so, just the two of us and, you know, you just get into the habit of doing it every week. I feel like Zoom is going to stick around and be the standard after the pandemic. I think it’s changed the way a lot of people think about co-writing. It makes you more disciplined and more productive. The technology just makes it easy. There’s no reason now for me to make a trip to Nashville, which is like four and a half hours, and get a hotel and all that when I can do all of it from home on my computer.

When you’re writing or doing work, are you the sort of person that has to change into regular people’s clothes to feel productive, or can you stay in your pajamas and be productive?

I think I’ve written at least a hundred of those 114 songs in my pajamas. [Laughs] I’m not going to dress up, I just want to be comfortable.

Photo credit: Ben Bateson