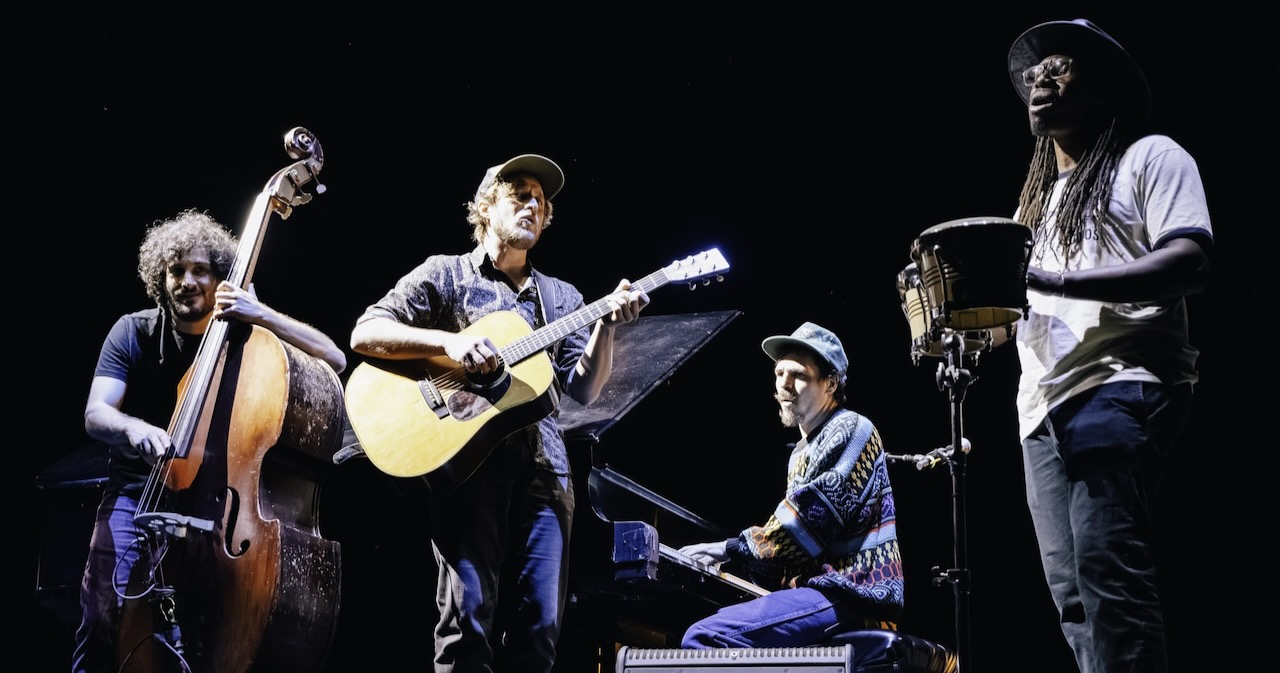

There’s something special that occurs when music is rooted in friendship and a shared mission. Perhaps no one exemplifies this better than Sam Grisman Project, founded by the youngest son of “Dawg music” pioneer David Grisman. Seeking to honor the likes of his father, Jerry Garcia & the Grateful Dead, and other musical heroes, SGP maintains a singular style and groove.

With its core iteration featuring seasoned multi-instrumentalists and songwriters Ric Robertson, Chris “Hollywood” English, and Aaron Lipp – and often featuring a host of other guests who run the musical gamut – SGP is bringing fresh authenticity, originality, and passion to the roots music and jam band scenes.

BGS spoke with Sam Grisman in early February 2024 about the origins of, inspirations, and plans for this remarkable and rising group.

What are the origins of Sam Grisman Project?

Sam Grisman: Ever since rekindling my musical friendship with the great Ric Robertson, who I’ve known since I was 14, I’ve been wanting to start a band that showcases the impact that the legacy of my dad and Jerry’s music has had on me. Ric and I started scheming on ways to make some music together and what that might look like. I figured we might have a good opportunity to play out in the live touring landscape if we paid tribute to the catalog of music that my dad and Jerry recorded together; that it could create the space for us to really do whatever we might want musically. We’re not limiting ourselves to the catalog of music that my dad and Jerry played together or individually, but we are honoring the spirit of what they did together, which was to dive into great songs that they had a shared love of.

I’ve always had a talented group of friends, going back to the time that I spent growing up at bluegrass festivals, fiddle camps, and the Mandolin Symposium. We have chemistry, and that is irreplaceable. Ric started playing music with Aaron Lipp around the time we turned 20 and he has been a part of my musical reality since then. He and Ric have developed strong chemistry, where they’ve been finishing each other’s musical sentences for years now. Aaron is from Naples, New York, about an hour away from Rochester, New York, which is where the great Chris English hails from. When Ric started making some music with Chris and telling me about what an amazing drummer and human being he is, I knew he would fit into the core of this band perfectly.

Who are you honoring with this project and why?

We’re honoring the musical heroes who influenced us the most. For me, because they provided the soundtrack to most of my earliest musical memories, that’s my dad and a lot of his friends who came through our house in Mill Valley to record. The friend who came around the most was Jerry [Garcia], but also John Hartford, Mike Seeger, Doc Watson, Tony Rice, Del McCoury and Ralph Stanley.

We honor our heroes, not just my dad and Jerry. We play lots of John Hartford music and Townes Van Zandt songs. Lots of Bob Dylan’s music, some Alan Toussaint, Dr. John, John Prine, Warren Zevon, Randy Newman, and Peter Rowan.

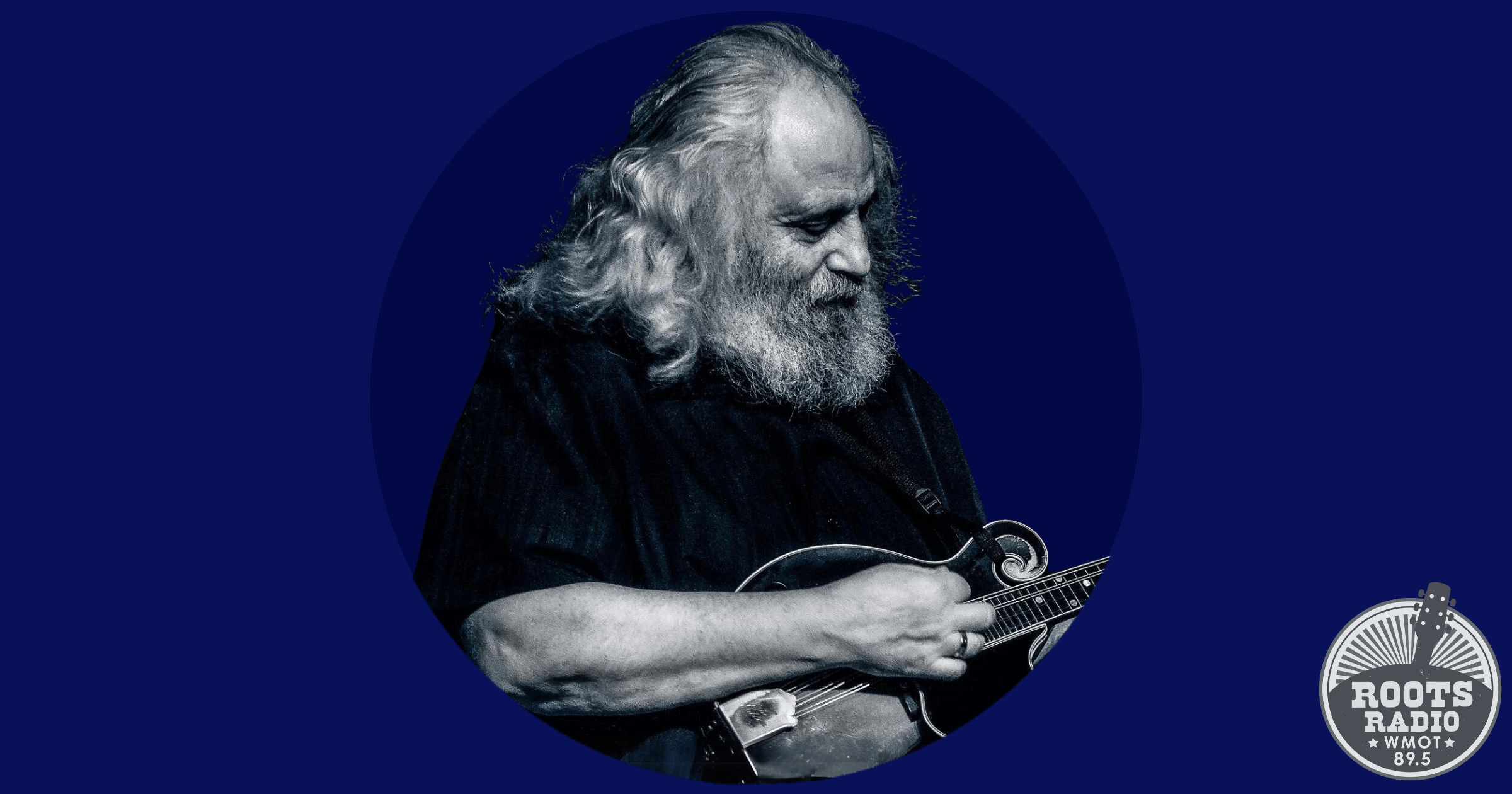

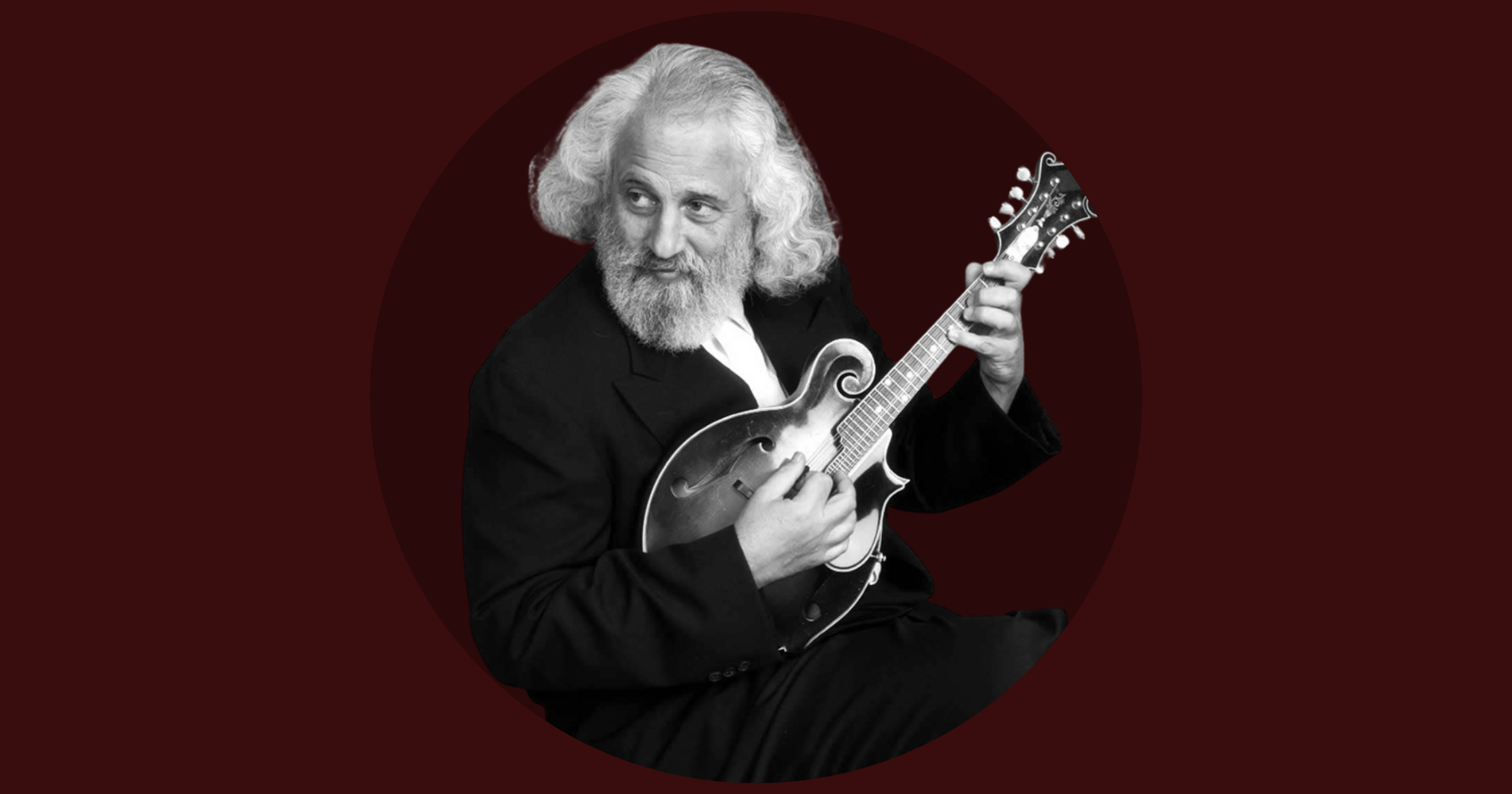

Can you describe what Dawg music is and what you’ve learned from your father?

Dawg music is a highly evolved form of acoustic music that is a synthesis of many different genres including old-time, bluegrass, hot club swing, jazz, and funk, with elements of classical music. It’s really a sort of genre-less genre pioneered by my father. It showcases – but is not limited to showcasing – the sound of the mandolin. The instrumentation in his quintet has traditionally been one or two mandolins, guitar, upright bass, and violin, but that’s expanded over the years to include percussion and drums.

That instrumentation of percussion, mandolin, guitar and bass is what I modeled the core of this band after. I’ve learned so much from my father about music and the music business – how to treat your friends and how to honor your elders. I am profoundly grateful to have been born to my particular set of parents and I’m grateful that there are other folks who have a deep appreciation for my dad’s impact on the musical landscape. I’d like for people to also appreciate how wonderful a human he is, so this is a small way that I get to share my dad with other people. He loves everybody, he’s grateful for the support, and he can feel it.

Who are some of the musical guests that have performed with SGP, and what does that mean to SGP?

It means a lot. It’s a representation of the community that we’re a part of. We’ve brought in some of our heroes as guests including dear family friends like Lowell Levenger “Banana” from the Youngbloods, Maria Muldaur, Eric Thompson, and Peter Rowan. We’ve had my dad sit in three times, which has been an absolute honor, and we’ve had a whole slew of our guests who bring different insights and a similar passion to the project: Dominick Leslie, Alex Hargreaves, Roy Williams, Bennett Sullivan, Nathaniel Smith, Phoebe Hunt, Lindsay Lou, my dear friend Tod Patrick Livingston, Mike Witcher, Chad Manning, Wyatt Ellis, Matt Eakle (the great flute alumnus from my dad’s quintet), and more. Eddie Barbash came and played a set with us in New York. Max Flansburg, who has a similar passion for this material and highlights a different corner of the Garcia/Hunter catalog than we do, played two of our New Year’s shows with us. We also had our old-time banjo hero, Richie Stearns, on all of those gigs that weekend. We’re going to have Logan Ledger on some shows coming up, and we’ll have Victor Furtado and Nathaniel Smith in the band.

When did SGP start touring in its current iteration, and how is the experience of touring with your best friends?

We had our first run as a band in January 2023. This conversation with you comes at the end of our longest break as a band, where we’ve had the entire month of January off. We’re starting back up on February 4th in Tucson, at a festival called Gem and Jam. It’s an absolute treat to travel the country with the people I care the most about, and to make great music and memories and friends everywhere we go. It’s important to anchor ourselves and ground ourselves in the music, because there’s a lot of work that goes into being out on the road that can make you lose perspective on how special it is to be doing something that you love for a living and to be able to do it for people who love what you’re doing.

SGP is obviously celebrating and continuing a particular musical legacy, but doing so with your own flavor. What makes SGP unique?

Our branding is our individuality and our honesty. I grew up in the house where my dad and Jerry recorded all of this music and I really do enjoy playing that music with my best friends. It gives me a sense of purpose to be able to play some of that music for folks who are passionate about it. There’s definitely room in the live music space for bands who take a preservationist approach to carrying on the musical traditions and catalogs of artists that came before them. A lot of musicians try to sound like their musical heroes, but that’s not our approach. I hired my friends to participate because I love their individuality and how they play, sing, and write music. I wouldn’t want to steer them towards sounding more like Jerry Garcia or my father.

We have been influenced by listening to tons of great music our entire lives, but we try to stay true to ourselves when we’re playing, so nobody is reaching for a sound that isn’t theirs. We all enjoy injecting our individuality into this music and having the flexibility to take the material in different directions depending on how we’re feeling. It’s amazing to have such versatile friends to work with.

How does original material fit into the broader vibe of SGP?

All three of the core guys – Ric Robertson, Aaron Lipp, and Chris English – are amazing songwriters. All the time I’ve known Ric, since we were teenagers, he’s been writing great songs. He was always a great singer, but he’s become one of my absolute favorite singers on the planet. There’s a lot of his music that lends itself incredibly well to looser, more long-form arrangements, which is something that SGP has become comfortable with.

Aaron Lipp is also an amazing songwriter who writes incredibly poignant music and aphoristic lyrics. Chris English writes amazing, feel-good music – not always overtly happy, but always with a strong message. His tunes add a lot of depth to our sets and take us to a more groove or bassline-oriented place, which is really refreshing for us and our audiences. I think there’s always going to be room for original music in SGP. As much as these guys are inspired to play their own tunes, I want to play them.

You released a great EP in 2023. Is there anything else currently in the works?

We’re gonna make a full length album at some point in 2024. Over the course of the last hundred or so gigs we’ve developed a pretty good repertoire and a strong rapport with each other. I don’t think it would take very long to put some of these tunes down in the studio, but we also multitrack most of our shows and we have an archive of live music to sort through. We’re going to be putting some shows up on Nugs.net pretty soon. We have a pro-taping policy to encourage folks to come and tape the show. I share Jerry [Garcia]’s philosophy that if you bought a ticket to the show, the performance is really yours as long as you’re not charging anybody else for it. Some of those shows have made it to archive.org, which is a free internet resource where folks can listen to live music. At some point we’ll probably put together some compilations of live material and put them up on the streaming services. I think our live show is always going to be the emphasis of what we do, so it’s important to have some recorded examples out there for people to check out.

What’s in store for SGP in 2024, and what does pursuing that mean to you?

We’ve got another solid year shaping up. We played about a hundred gigs in 2023 and we’ll probably make it pretty close to that in 2024. I’m going to expand the cast of characters a little bit in 2024 and bring some other friends into the fold. I’m looking forward to introducing my new friends and audiences to my dear musical compatriots who care about this music as much as I do. I’m grateful and humbled to get to do it. It means a lot to get to honor my father every night by playing his music. We take out the mandola that he gave me for my 21st birthday, the mandola he recorded “Opus 38” on. We get to play “Opus 38” on that very same mandola for people who appreciate what’s happening, and I feel like he and Uncle Jerry are with us every night. It’s a big blessing all around.

Photo courtesy of the artist.