Tyler Childers has taken an unlikely path to the top via live performance, not radio singles. He’s become an improbable arena-level star by ignoring typical Nashville bromides – equal parts Patterson Hood’s working-class Southern blues, Chris Stapleton’s bluegrass bonafides, and Woody Guthrie’s progressive populism. After all, you’re not gonna call your touring band The Food Stamps unless you lean left, at least a little.

Like Billy Strings, Childers has become enough of a sensation for his appeal to extend beyond the Americana-adjacent world, too. Last year, he even turned up onstage for a live cameo with pop star Olivia Rodrigo in his Kentucky stomping grounds to do his song “All Your’n.” It went over like a house on fire.

Since country radio is finally, belatedly catching on with “Nose On The Grindstone,” lead single to Childers’ fine new Rick Rubin-produced LP Snipe Hunter, let’s take a look back to where he came from.

How’d this happen, anyway? Like this.

“Hard Times,” Bottles and Bibles (2011)

Going back to the beginning, “Hard Times” was the song that opened Childers’ full-length debut Bottles and Bibles. It’s an actual hillbilly elegy that definitely sets a tone, with finely detailed lyrics that unfold like a short story. Simultaneously stoic and emotional, Childers’ quavering vocal about a holdup gone wrong makes him sound like a protagonist who somehow regrets both everything and nothing at all: “And if the Lord wants to take me, I’m here for the taking/ ‘Cause Hell’s probably better than tryin’ to get by.”

“Long Violent History,” Long Violent History (2020)

Bluegrass roots and of-the-moment progressive activism makes for an unusual combination, but here we are. “Long Violent History” is the title track to a bluegrass album and it’s the only original and non-instrumental track on the record. Evoking “Faded Love” at the outset and “My Old Kentucky Home” on the outro, it’s a rural Southern score for the Black Lives Matter protests that swept America in 2020.

“It’s the worst that it’s been since the last time it happened,” Childers sighs at the outset, resigned to the inevitability of violence happening again. For good measure, Childers made a supplemental spoken-word video (below) explaining the necessity of BLM: “If we didn’t need to be reminded, there would be justice for Breonna Taylor, a Kentuckian like me, and countless others.”

“Jersey Giant” – Elle King (2022)

If Childers ever records his own version of “Jersey Giant,” he’ll have to hustle to top Elle King’s cover. As with the similarly themed “Me and Bobby McGee” (written by Kris Kristofferson, but owned for the ages by Janis Joplin), King just completely inhabits the song’s bittersweet, longing anguish. “I left town when we were over… Just didn’t feel the same” – the way she pauses a beat between lines is just chef’s-kiss perfection. There are numerous cover versions of “Jersey Giant” out there, but this is the one that’s going to linger.

“Luke 2:8-10,” Rustin’ In The Rain (2023)

Remember the big pivot-point moment of truth in the classic holiday cartoon A Charlie Brown Christmas – the “Lights, please” speech that his friend Linus makes? Childers must have grown up with that, too. Linus spoke these Bible verses, Luke 2:8-10, which Childers transposes to the key of honky-tonk in this song with his drawl in full effect. You can almost imagine the “Peanuts” dancers doing a two-step to it.

“Purgatory,” Can I Take My Hounds to Heaven? (2022)

Childers’ ambitiously wide-ranging 2022 album Can I Take My Hounds to Heaven? featured eight gospel songs, each done in three different versions dubbed Hallelujah, Jubilee, and Joyful Noise. The latter category tricked each tune up with samples and remixes, which might be the closest Childers has ever come to hip-hop electronica (at least so far!). In this guise, the title track from his 2017 project Purgatory cuts the sort of groove you’d expect to hear in New Orleans.

“The Heart You’ve Been Tending,” Harlan Road – NewTown (2016)

What does it mean that so many of the best covers of Childers’ songs are by women? Who’s to say, but here’s another great one, from the Kentucky band NewTown’s Harlan Road album. “The Heart You’ve Been Tending” is in waltz time, with fiddler/singer Kati Penn’s vocal shining bright as a lighthouse cutting through a foggy mountain breakdown.

“In Your Love,” Rustin’ in the Rain (2023)

Another multimedia project of sorts, this song from Childers’ Rustin’ in the Rain started out as a relatively conventional devotional love song. Then he enlisted collaborators including his fellow Kentuckian, author Silas House, to make a video that casts “In Your Love” as a sort of country music version of Brokeback Mountain set in coal-mining country. As beautiful as it is heartbreaking.

“Matthew,” Country Squire (2019)

Childers has always been wildly eclectic and this song from his Country Squire LP is a prime example. “Matthew” is yet another working-class waltz, with enough bluegrass savvy to drop bluegrass legend Clarence White’s name in the lyrics – plus an actual sitar as oddball sound-effect mood-setter at the beginning of the song. Somehow it makes perfect sense.

“Bottles and Bibles (Live),” Live on Red Barn Radio I & II (2018)

With or without a band, Childers has always been a riveting performer. This live version of the title track to his 2011 studio debut closed out 2018’s Live on Red Barn Radio I & II and it’s just voice and guitar. All the better to focus on the tale of a preacher as wayfaring stranger pondering the difficulties of keeping to the straight and narrow: “But they ain’t had to walk with the weight that you’ve hauled/ They don’t know you at all, but they think that they do.”

“Coal,” Bottles and Bibles (2011)

What might Bruce Springsteen have been like if he’d grown up in a Kentucky coal-mining family? You can imagine him turning out like the narrator of this song, which sounds way too timeless to have originated in this century. It’s pure working-class desperation: “We coulda made something of ourselves out there, if we’d listened to the folks/ That coal is gonna bury you.”

“Oneida,” Snipe Hunter (2025)

To be a Childers fan is to accept that he does have some idiosyncratic boundaries. There are songs from his live shows he’s never recorded, like the previously mentioned “Jersey Giant”; or popular recorded songs he has sworn off playing live, including the now-widely-seen-as-problematic “Feathered Indians.” For the better part of a decade, one of his unrecorded orphans was “Oneida,” a longtime fan favorite that’s like a Harold and Maude for the country set. Lo and behold, a recorded version finally surfaced as one of the best songs on Snipe Hunter. Dreams do come true.

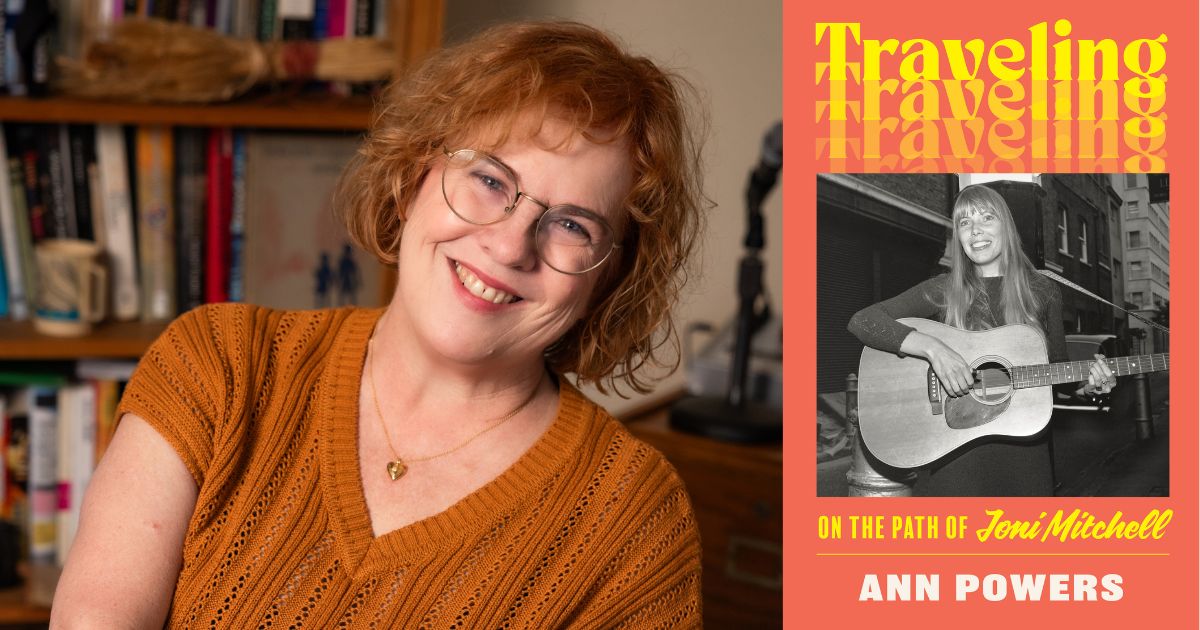

Photo Credit: Sam Waxman