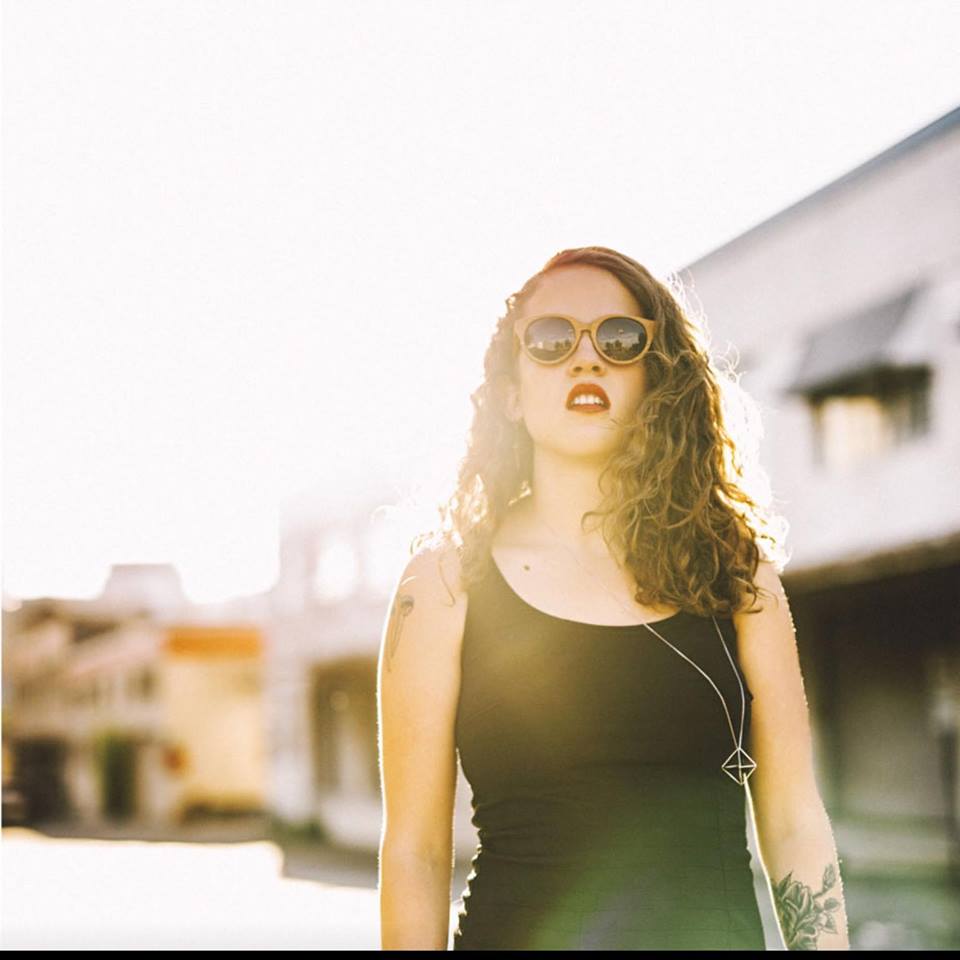

On first listen, it would seem Sallie Ford and Charlie Cunningham have little in common, except that they are human musicians. A singer/songwriter born in North Carolina but based in Portland, Oregon, Ford writes soul-baring lyrics that reveal a caustic wit, a persistent self-deprecation, and an abiding love for doo-wop, rockabilly, punk, and crunchy guitars. With her backing band, the Sound Outside, she released two albums, then went solo with 2014’s Slapback. But her latest, Soul Sick, may be her best yet: a set of lean, mean songs that reveal an ongoing battle with her baser urges, an emotional landscape where “the feeling of failing … is freeing.” Her music is blunt and direct, like a fist applied swiftly to your jawline.

Cunningham’s music, by contrast, starts as a gentle caress but ends as a deep scratch — fingernails digging into skin to draw blood. Through a series of EPs and singles, this London-born, Oxford-based musician has established himself as a formidable guitar player and a songwriter with a brutal economy of language. “I’m not here to pick a fight,” he sings on “An Opening,” “but we can, if you like.” Released on the Swedish label Dumont Dumont, his debut album, Lines, is taut and tense, with flourishes of synth and drums that underscore his percussive guitar playing.

Aside from a certain musical violence, Ford and Cunningham happen to share an understanding of music as a fundamentally cathartic endeavor, of songs as vehicles for the kinds of dark secrets you wouldn’t normally admit to a roomful of strangers. Never exactly grim nor simply self-absorbed, they are hyper-confessional lyricists, which means their albums are equally harrowing and relatable. Beyond that, they both come across very differently in conversation than they do in their music: amiable and animated, Cunningham speaking quickly and Ford punctuating her remarks with a piercing laugh.

One of the reasons I wanted to get you two on the phone together is that you’re both incorporating some styles that I don’t hear in a lot of music right now — Sallie with doo-wop and early rock, Charlie with flamenco. Those styles seem integral to your songwriting, rather than just sounds you’re dabbling in.

Sallie Ford: I just like retro music, in general. I grew up listening to a lot of oldies. My parents really liked the Beatles and Aretha Franklin and James Taylor, and we would have dance parties in the living room. [Laughs] So a lot of my music is about nostalgia. If you’re going to be influenced by anything, it has to be something that just calls you. What about you, Charlie?

Charlie Cunningham: First, I want to say well done on your album. There’s so much going on there, especially on that song “Unraveling.” You can definitely hear your soul influences coming through. As for me, I’ve always liked all sorts of music, but particularly acoustic guitar music. I used to listen to a lot of people like John Martyn and Nick Drake and Leonard Cohen — those kinds of people, playing that finger-picking style. I wanted to learn how to do that. I’d run out of tools, as far as playing goes. I went for flamenco because it seemed like the kind of thing I could understand. It sounded alien, but it also sounded somewhat familiar. It sounded very human and relatable. Once I did learn it, I was off. It just took a long time. I don’t know about you, Sallie, but it took me a very long time before I was ready to say, ” Here’s my music, people. This is what I do. This is me singing. This is me playing guitar.” That was the biggest hurdle for me.

SF: I grew up playing music, but it always mortified me to perform in front of people. My mom would have to make me. I played classical violin, and she would throw these concerts at her friends’ houses, and I would just die from embarrassment. It took me moving to a new city where no one knew who I was to realize that maybe I actually did like performing. Which is strange, because my whole family are performers. They’re much better than me. My father is a puppeteer, and he would make puppets with us. We lived way out in the boonies, and I was home-schooled. It was a pretty unusual upbringing. What about you?

CC: I was born in London, but I grew up about an hour outside of the city in a bit of country. I say “a bit of country” because you have these cities like London and Birmingham and Northampton, and then you have the bits of country between them. I lived in one of those. There was always music playing in my house, but there weren’t many players in my immediate family. My granddad used to sing. I’ve got lots of brothers and sisters — I’m one of five — and we were always trying to out-sing each other, not with any kind of skill, just in terms of volume. It was mainly a thing I did on my own, really. Music struck me early. I’d watch a lot of MTV, back when it was just one channel, and VH-1, and I stared to get interested in the world of music. We listened to a lot of Stevie Wonder and Elton John and these classic songwriters at a very young age … Why does my answer suddenly seem so much longer than yours?

SF: Ha! I think you’re just good at talking. I tend to clam up.

CC: I don’t think I am. You’re quality over quantity. Anyway, do you feel any relief now that your album is done, or do you feel anxious putting it out there in the world?

SF: I’m really excited. I’ve had a whole year off, and I have a new band, so I’m excited about all that. This will be my fourth album, which is crazy. But one thing I am nervous about is just now realizing how hard it is to be a musician, and I think it’s getting harder with digital downloading. Are you familiar with that really nerdy TV show in the U.S. called Nashville?

CC: No, I don’t know it.

SF: It’s not great. It’s a lot like a soap opera, but the reason I bring it up is because they’re all talking about how musicians are being affected by downloads. The fact that they’re talking about it on a major network television show about pop-country musicians is scary to me. I’m like, “Oh my god, what did I get myself into?” Maybe it’s not as bad in Europe, so I guess I could stop touring the U.S. and just tour over there.

CC: When I was listening to your stuff, there’s definitely this sense of being aware that what will be will be — like in that song “Failure,” when you’re talking about failure being freeing and a fleeting thing. That’s a good way to think about doing music, just knowing not to expect much. It really can be liberating. It does free you up writing-wise, because you don’t have to worry if it will sell. I think live music is one of the only things now that’s actually flourishing, perhaps more than ever, just due to the fact that people have to play gigs and tour to make a living. That’s the only way I can do it. So, in a way, maybe there are some positives, but it’s a bit of a Wild West, at the moment.

SF: I feel like I’ve written my most important album, and it’s just … I’m trying not to think about the past and how it’s been such a struggle. I want to change my way of thinking. I feel like I’ve been doing this long enough that I start to make assumptions about how things are going to go. Maybe that’s just how I am — always preparing for the worst.

CC: Preparing for the worst and hoping for the best.

SF: That is my motto, actually, although I word it slightly differently: No expectations, high hopes.

CC: That’s the only way to be, isn’t it? Because, at the end of the day, it’s the music that’s going to stay forever. That’s not going anywhere. That’s your thing that you’ll look back on and say, “I’m so glad I did that.” And it’s such a good record. I like the guitar sounds. What’s going on with the guitars there? Were those vintage amps?

SF: Yeah. I have tube amps. It’s actually all new equipment, but it’s modeled to sound old. I really dig Fender guitars, especially if you put them on the most trebly sounding pickup. I really love a thin, trebly sound. I love surf music. Actually, when I first learned guitar, my first teacher was trained in flamenco playing. He could do all this fast picking because of that training. He got some of the chops. Here’s a question for you: Do you play solo when you tour, or do you have a band with you?

CC: I’ve been playing solo for the last couple of years, but I’ve got a European tour starting pretty soon and there are going to be a couple of other people on stage with me. It’s still really minimal stuff, just some light percussion and some soft synths underneath to give it a bit of a lift. It’s still fairly simple and calm stuff, nothing too dramatic. I think the only way I was able to play music for the last couple of years was to do it on my own. Otherwise, it’s just too expensive to travel with a group of people. But I could usually say yes to anything because it’s just me and my guitar and a bag. But now I think I could probably justify getting some people on board, so I’m looking forward to traveling with other people for a change.

SF: Sometimes I think I might go back to doing that. I never did it that much. I did open mic nights, when I first started playing. My biggest goal right now is to go to Japan, and I feel like that’s not going to be a money gig. So maybe the next record will be a solo record that lets me tour in Japan.

Why do you want to go to Japan?

SF: I went to Japan when I was 12 because I had a bunch of pen pals. Since I was home-schooled, my parents would let me write to pen pals as part of my homework. So I would spend hours researching the countries they were from, and I was obsessed most of all with Japan. I learned Japanese and had a Japanese teacher, and she took me back with her to Japan to meet some of my pen pals. I’d really like to go back. I find that most Americans are pretty fascinated by Japan. What’s your dream tour, Charlie?

CC: To be honest with you, I really want to tour across the pond in your part of the world. I’ve never played a gig in America, but I’m coming over for the South by Southwest festival in March. Hopefully I can get some other dates during that trip. That would be fantastic. It’s a bit of a dream, but growing up in England, watching the telly and listening to American music, we knew American culture really well over here. So I think it would be interesting to see it and play some gigs over there. I’m just going to go over on my own, not with a band or anything. So, you’re from Portland, right?

SF: I lived here for about 10 years. I moved from this little city in North Carolina called Asheville, which is like a miniature Portland but not as famous. It’s one of the most liberal college towns in the South. Have you heard much about Portland over there?

CC: I’ve been to the States once, and one of the places I went was Portland. I went there and Seattle. I really like Modest Mouse, so I was excited to see the city. I heard this band called Mimicking Bird. Did you ever hear them? I think they’re on the label that Isaac Brock from Modest Mouse runs. It’s really nice music. And Johnny Marr from the Smiths lives in Portland, I think. I’ve seen that program Portlandia, as well, which I love.

SF: So many cool musicians who live here, for sure, but it still feels like a small town. That’s what I like about it. You run into people you know all the time, and most people know each other, especially in the music scene. Most of the time people aren’t very competitive with each other.

CC: A little bit of healthy competition can be okay, but generally you need to be supportive. That sense of community is important. I think that’s why I keep ending up back in Oxford. There’s a sense of community here, and good music. People go to each other’s shows and they keep an eye out for what everybody else is doing. That really helps the creativity and makes you feel involved.

What took you to Oxford?

CC: It’s not a million miles away from where I grew up. Basically, I grew up between Oxford and London, and I ended up studying there — not at Oxford University. I should just clear that up right now. But I did study at a university in Oxford for a little bit. I met a lot of people there, and there’s a big music scene going on there. You’re only an hour away from London, so you can be really involved in that scene, but then you can step out of it and be in this much smaller town. It’s an inspiring place to be. There are lots of people from all over the world in Oxford, because of the university. So you get to meet a lot of different people. And I love a bit of history. It’s nice to walk into town and see all these really old buildings. It’s a clam place to be. When I get home from touring, Oxford is a good base. I’ve lived here for eight or nine years total, but I keep moving away and coming back. Maybe I’ll end up staying a bit longer this time.

SF: I saw something on your Facebook about how you went to Abbey Road. What was that like?

CC: Yes! I went there to master the album. I recorded it in New Cross in south London, and then I did the mastering at Abbey Road. What a great day that was. I was such a Beatles fan when I was growing up, so it was just crazy to be there. You go through the studio and see all these pictures of people who have played there. And it’s everyone. It felt humbling, and I was really trying to be present for it. There’s a lot of stuff that happens and you don’t sit with it properly, but I spent most of that day really trying to take it all in. And they did such a job with the mastering. They really took it to another level, and it was incredible to watch and hear that happen.

Here’s a quick question for you. That song “Get Out,” is that about trying to get songs out of you, trying to get music out of yourself?

SF: I love that interpretation. It’s cool when songs can mean different things to different people. When I wrote it, I was thinking about how I tend to give up pretty easily. If I’m feeling overwhelmed by a situation, my first inclination is to remove myself, especially struggling to do music. It’s overwhelming, and I tend to give up on things too quickly. I’ll take some new class or try some new hobby and, before I even start, its like, “Oh no, I’m already over this.” You can’t do that before you’ve even started. You can’t be the best at something as you’re learning to do it.

I recently took this weird circus class, and I had this competitive feeling, like I want to be really good at it. But it was so hard and I struggled so much that I swore in front of the whole class. They were trying to get me to hang upside down, and I finally went, “Screw this!” It was the very first class. I made the mistake of going with my friend who was really good at it. I was jealous.

CC: At least you went to the class. Some people might not even try. I think that’s admirable.

SF: I started doing hip-hop dancing a few years ago. I was pretty bad, but it was so much fun that it kept me coming back. I would never do it in front of anyone, but there’s so much about it that I love. It shuts your mind off. Everybody talks about yoga shutting your mind off, but for me, it’s dancing.

CC: I used to dance a lot more than I do now. I need to dance more. I used to enjoy going to clubs and dancing, but when I got older, I got more self-conscious. Maybe that’s something to fix. Maybe when I’m in Austin, I should have too much to drink and end up dancing somewhere. Note to self …

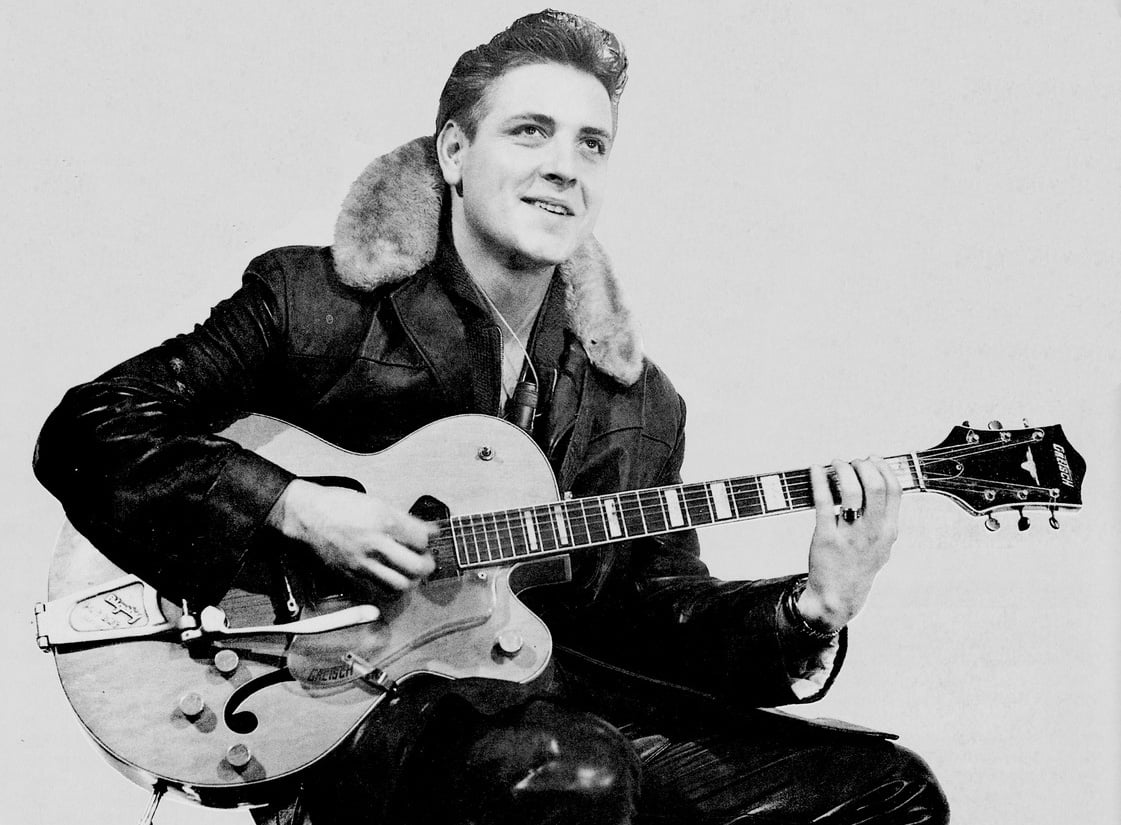

Sallie Ford photo by Kim Smith-Miller. Charlie Cunningham photo by Louisa Stickelbruck.