“No, no, no, no.”

Ry Cooder is quick to put something to rest as he talks by phone from his home in the hills above Pasadena, California.

Yes, he and Taj Mahal went a full 54 years between recording projects together — from Cooder playing on Mahal’s 1968 solo debut, which grew from them co-fronting the band Rising Sons, to right now for the duo album Get on Board: The Songs of Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. The thing is, in the decades that harmonica master Sonny Terry and Piedmont blues virtuoso Brownie McGhee worked regularly together, from 1939 to the early 1980s, they were often at odds, sometimes not even speaking to each other off stage.

But no, there were no rifts between Cooder and Mahal, no disputes, no bad feelings that kept them apart.

“Nothing like that!” Cooder insists. “No, no, no!”

The time between projects?

“Musicians, you know,” Cooder says. “He travels around all the time.”

Yet, in other regards…

“It’s funny,” says Mahal, on a separate call between tour stops, “because we’ve actually become the men that we admired. We’re the new version of it, you know? So, it’s like full circle. It’s a wonderful thing to have really accomplished that, to be in a life in music.”

The way Cooder and Mahal have become the men they admired, presumably, is in the role of elder statesmen keeping traditions alive. They are honoring and, in highly personalized ways, refreshing the music with deep ties to past generations and cultures. That full circle — global circumnavigations, really — has seen them explore a wealth of music and cultures, from Cooder’s key role in Cuban group Buena Vista Social Club projects, to Mahal’s drawing on the Afro-Caribbean roots of his musician/arranger father. Their individual efforts include collaborations with musicians from Africa and India, just for starters. But with this album they each go back to where the sparks for all that first happened.

For Cooder, it started with the first Terry/McGhee collaborative recording, also called Get on Board, a key release in the essential catalog Mo Asch created on his Folkways label. In fact, the new tribute album not only uses the title but has cover art that is an homage as well. The full title of that 1953 album was the now archaic Get on Board: Negro Folksongs by the Folkmasters.

Sonny Terry had come to some mainstream recognition as part of the original cast of Finian’s Rainbow on Broadway in the late 1940s, and as a pair he and Brownie McGhee were featured in the Broadway productions of Tennessee Williams’ Cat on a Hot Tin Roof and Langston Hughes’ Simply Heaven. They were also championed by Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie and Harry Belafonte, among other prominent supporters. But for young Cooder, this record was a discovery marked by its vibrant energy, with Terry and McGhee joined by one Coyal McMahan on vocals and percussion.

“It’s a great record,” Cooder says. “You’ve got the mysterious Coyal McMahan on bass voice, sort of a church bass, and maracas. They should have kept him on. I don’t know why they didn’t. He added a whole other quality to it. I don’t know who he was and nobody knows at this point.”

The new album features three of the eight songs on the Terry/McGhee set — “Midnight Special,” “Pick a Bale of Cotton” and “I Shall Not Be Moved.” Its remaining songs are part of the icons’ other recording and live repertoire, from the reverent “What a Beautiful City” to the carousing “Drinkin’ Wine Spo-Dee-O-Dee” to the double-entendre “Deep Sea Diver” to the down-and-out “Pawn Shop Blues.”

Adding their own touches to the songs, Cooder and Mahal recorded mostly live in the living room of Cooder’s son, Joachim, who also played various percussion instruments and bass, sort of filling the McMahan role (and more). They didn’t seek to recreate the originals. What they did do, was have fun.

“That was the intent,” Cooder says. “I mean, it seemed to me that we could pull it off and keep that feeling that those guys had back then. I don’t want to say ‘jolly,’ but foot-tapping, nice music. They had gone for a white audience, I’m pretty sure, at that point anyway. So, you couldn’t very well play very dark music at white people in those days. They wouldn’t know what you were talking about, what it was for. By the time they started recording together, I guess, black popular music had changed radically.”

Cooder is conscious of the radical changes since then in music and culture, in particular noting “Pick a Bale of Cotton.”

“They’re still really good songs,” he says. “And I think people will like hearing them as much now as they liked hearing them back when Brownie and Sonny did them. It’s a different time now. Of course everybody’s consciousness is totally different. I mean, everything is different.”

That’s part of the point, not to let the music that inspired them get lost.

“It just feels like old times,” Cooder says. “I have those records from when I was a little kid, so I can dig it. I remember how it used to make me feel listening to the record, how tremendous it was, how exciting it was.”

The circle for Mahal goes back to the early 1960s, when he was a student at the University of Massachusetts.

“There was a whole network for folk music and blues and bluegrass and country and all that old-time stuff in and around the Northeast sector,” he says. “I was like 19, 20 years old. And those guys were coming through and playing at local coffee houses. You could get to see them quite a bit. And I thought they were just an incredible powerhouse duo.”

A couple of years later, Mahal, who had started playing on the folk circuit himself, encountered a guitarist with a great feel for blues.

“I said, ‘Well, where the heck did you learn how to play like that?’” Mahal remembers. “And he said, ‘Well, you know, I took some lessons from this guy out in California named Ry. I said, ‘Do you think that guy might like to be in a band?’ And he said, ‘Well, he’s only 17 years old.’ I said, ‘Are you kidding me?’ And I said, ‘I guess I have to go to California.’”

And he did. When they connected, a love for Terry and McGhee was one of their bonds. Cooder, too, had seen the duo play a few times by then, the first coming when they played at the opening night of the Ash Grove, a Hollywood club that would become the center of the California folk and blues scene.

“My mother took me down there,” Cooder says. “I was 13 or so. I sat there and watched them. My gosh! It was something to see the whole thing come to life. You know, it was a tremendous impression when you’re young like that.”

And when they’re not-so-young. (Cooder just turned 75 and Mahal will be 80 in May.) They first chatted about teaming for a project after Cooder joined Mahal at the 2014 Americana Music Honors & Awards at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium on Blind Willie McTell’s “Statesboro Blues,” a staple in the Rising Sons repertoire and a standout on Mahal’s 1968 album. That latter version, which featured Jesse Ed Davis on electric slide guitar, is reputedly the recording on which the Allman Brothers’ rendition was modeled.

When Cooder suggested an album honoring Terry and McGhee, Mahal was, well, on board. “Those guys are foundational titans,” Mahal says. “Here’s a guitarist and harmonica player that spanned 40 years, at least.”

But these musicians are also largely forgotten, which adds a sense of mission to this project, to rekindle interest in the guys whose recordings and concerts meant so much to them.

“If you stood on a corner and did an exit poll and talked to a million people, none of them would know who they are,” Cooder says. “They’ve been completely overlooked. I don’t know anybody that’s ever heard of them or remembers who the hell they were, except for musicians who have made it a point to keep certain things in mind. It’s like bluegrass. If you keep Bill Monroe or Reno & Smiley in mind, it’s that kind of thing. That’s how you live, and that’s how you evoke things, this memory that you have of these records.”

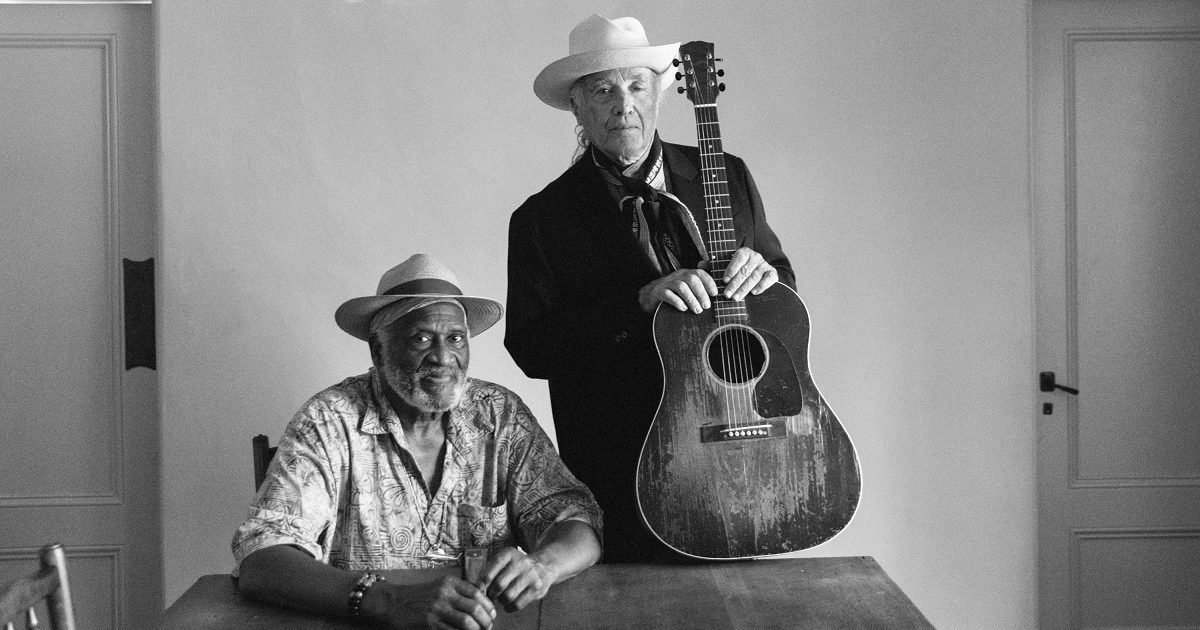

Photo Credit: Abby Ross