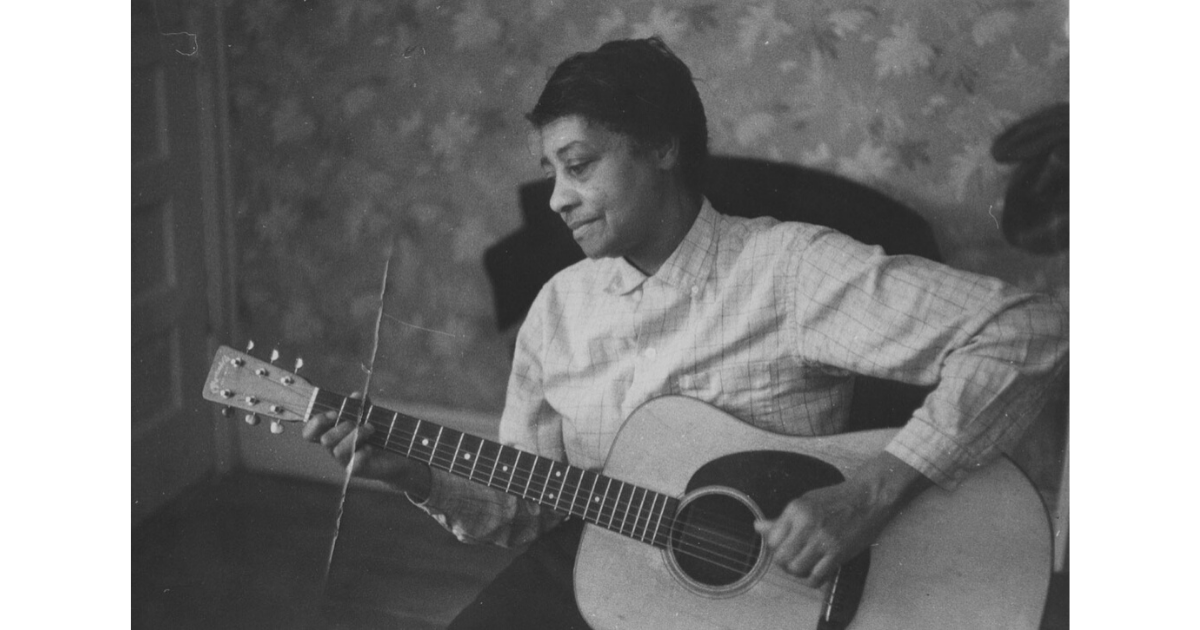

You can’t tell the story of country music without June Carter Cash.

Her mother, Maybelle Carter, helped usher in the era of commercial country music through the 1927 Bristol Sessions as a member of The Carter Family. When that group disbanded, Maybelle eventually gathered her three daughters – June, Anita, and Helen – and started performing radio shows, with June playing autoharp and cracking jokes. (They even had Chet Atkins in their band.)

In time June teamed up with comedians Homer & Jethro for a corny duet of “Baby It’s Cold Outside,” which charted for one week in 1949, and by 1950, the Carter Sisters debuted at the Opry just a month before June’s 21st birthday. The ensemble opened shows for Elvis Presley in 1956 and 1957. June also stepped out as a duet partner with her first husband, Carl Smith, on the eye-rolling (but quite hilarious) “Love Oh Crazy Love,” from 1954.

If your entry point to country music is the 1960s, June Carter is all over it. Still married to Smith, she shared the stage with Johnny Cash for the first time in 1961 as part of his touring package. Two years later Cash scored a major hit with “Ring of Fire,” which Carter co-wrote after seeing the phrase “love’s burning ring of fire” underlined in a book of Elizabethan poetry owned by her uncle, the Carter Family’s A.P. Carter.

By 1967, she and Cash landed a major hit (and soon their first Grammy) with “Jackson,” then got hitched in 1968. It’s important to remember June’s role on Cash’s landmark 1968 album, At Folsom Prison, performing a lively rendition of “Jackson” that got the captive audience hollering. They encored the performance for Cash’s 1969 album, At San Quentin.

June Carter Cash did pretty well for herself in the next decade, too, having her own 1971 country hit with a song she wrote, “A Good Man.” Johnny Cash produced her sole album of that era, 1975’s Appalachian Pride, even as they dug periodically into the folk canon for duet recordings and she won her second Grammy for the Cash/Carter duet, “If I Had a Hammer.”

She appeared regularly on the groundbreaking series The Johnny Cash Show, sang on Cash’s records, and almost always toured with him. Considered more of a comedian than a vocalist, June nonetheless charmed audiences around the world. In the rarely-seen 1979 performance of “Rabbit in the Log” below, she steals the spotlight with a banjo on her knee, cracking jokes and sharing her talent with a Century 21 real estate convention in Las Vegas.

Even listeners who came into country music in the ‘80s and ‘90s can find a tie to June. She harmonizes with her sisters, as well as Johnny Cash, on “Life’s Railway to Heaven” on Nitty Gritty Dirt Band’s seminal 1989 album, Will the Circle Be Unbroken, Volume Two. Around this same time Carlene Carter, her daughter with Smith, emerged as a force in country and rock, and later paid homage to Mother Maybelle as well as June’s stepdaughter, Rosie Nix (from June’s second marriage), on the sweet song, “Me and the Wildwood Rose.” Carlene also wrote one of that era’s most enduring compositions, “Easy From Now On,” and charted multiple singles like “I Fell in Love” and “Every Little Thing.”

Meanwhile, Rosanne Cash (June’s stepdaughter) placed 11 No. 1 singles on the country chart, including the modern classic, “Seven Year Ache,” and she’s now a cornerstone of the Americana community. John Carter Cash, the only child born to Johnny and June, continues to carry on the brilliant legacy of his parents, through books, museum presentations, and reissues. He also produced Loretta Lynn’s past three albums at the Cash Cabin recording studio in Hendersonville, Tennessee.

Johnny Cash, incidentally, was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1977 and the Country Music Hall of Fame in 1980. A.P. Carter joined the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1970, “Ring of Fire” co-writer Merle Kilgore followed in 1998, and Rosanne Cash entered in 2015. However, June Carter Cash is not yet a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame or the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame — omissions that deserve reconsideration. A spiritual and religious woman, she shared the stories of her life in two memoirs: 1979’s Among My Klediments and 1987’s From the Heart.

Always a natural on stage, June actually trained at the Actors Studio in New York City after being spotted by Elia Kazan at the Grand Ole Opry in 1955. In the late ‘90s, she drew upon those thespian skills with roles on Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman and the acclaimed film The Apostle. Not to be overlooked is her heartbreaking role in Johnny Cash’s 2002 video, “Hurt,” where the viewers sees the devastation of an American music legend through her shocked and tearful eyes.

Carter remained a legendary presence in the final years of her life — and beyond. Her 1999 collection, Press On, won the Grammy for Best Traditional Folk Album, while the Carter Family classic “Keep on the Sunny Side” resurfaced in a major way due to its inclusion on the O Brother, Where Are Thou? soundtrack in 2000, as sung by The Whites.

Following June’s death in 2003, she was awarded two more Grammys – one for her own performance of “Keep on the Sunny Side,” and the other for the folk album, Wildwood Flower. Nashville native Reese Witherspoon collected an Oscar for portraying her in the 2005 film, Walk the Line. A two-disc compilation released that same year surveyed her remarkable career. She is buried next to Johnny Cash in Hendersonville, Tennessee.

Photo credit: Don Hunstein, Sony Music Archives