Tag: Bela Fleck

Hangin’ & Sangin’: Jerry Douglas

From the Bluegrass Situation and WMOT Roots Radio, it’s Hangin’ & Sangin’ with your host, BGS editor Kelly McCartney. Every week Hangin’ & Sangin’ offers up casual conversation and acoustic performances by some of your favorite roots artists. From bluegrass to folk, country, blues, and Americana, we stand at the intersection of modern roots music and old time traditions bringing you roots culture — redefined.

With me today in the Writers’ Rooms at the Hutton … Jerry Douglas. Welcome!

Hello. How are you?

I’m good. How are you?

I’m good. I’m having a wonderful week.

Yeah, you’re getting puppies!

I’m getting puppies today! I’m getting puppies today. My granddaughter’s at the house — another puppy, then I’m gonna go see my new grandson on Sunday — more puppies. It’s puppy week!

That’s good livin’!

It is good livin’. I love it.

Okay. Let’s talk about this dobro thing that you’ve got going on.

I’m sorry. [Laughs]

As you should be. [Laughs] What was it about the dobro that first lured you in, so many moons ago?

I don’t know if it was the dobro by itself or the guy who was playing it. Josh Graves played the dobro with Flatt & Scruggs, and he was the one that made me want to become a musician. It wasn’t just the way he played it, because I was hearing Bashful Brother Oswald, at the same time, playing with Roy Acuff and that was good, but Josh Graves stepped up to the microphone and he blew the doors off the place! He could keep up with Earl Scruggs, and he played bluesy, too. He played the blues. I think that was the difference for me, because I was growing up close to Cleveland, Ohio, so I was hearing a lot of rock ‘n’ roll at the same time, and it all worked for me — made the instrument work for me.

My dad had a bluegrass band, but there wasn’t a dobro player within a million miles of me. [Laughs] I told somebody the other day that I stood a better chance of getting hit by a car than to find a dobro. It was not something you saw and they didn’t know what it was. You’d go to a music store and say, “Do you have any dobros?” and they’d look at you like …

But you found each other.

We did.

You’re like Béla Fleck with the banjo, to me. Musically, you guys both do things with these instruments that isn’t normally expected. Who’s leading that exploration — is it you or the instrument? Are you following where it’s taking you?

I’m trying to take the instrument to new places. It’s a great bluegrass vehicle, which has been proven over and over again, with Josh Graves and Mike Auldridge and Rob Ickes. There are several people who really can play one of these things. But I keep exploring and trying to find other ways to use it — in classical music, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll. I created a pickup that works with it that keeps it sounding like a dobro, but you can play to a 24,000-seat place without feeding back. You can compete with a telecaster.

Nice. Do you ever get tired of it and think, “I’m gonna switch to the French horn” or something? Does the mastery ever stop? Is it every complete? Or is there always something new to learn and explore?

There’s always something new. I keep my ears open, and I sort of adapt other things to the guitar. The guitar’s a conduit of whatever’s in [my head], what’s rolling around in there all by itself. It’s a cobwebby place. [Laughs] But I think that I’m kind of trying to lead it from one place to another, but I do get tired of hearing it. I got so tired of it that I started carrying around refrigerator-sized racks of things to make it sound not like a dobro. And then I got tired of that, and I just wanted to hear a dobro again! So it’s a necessary evil.

But I love the sound of the guitar. These newer guitars don’t sound like the dobros did that were on the records that I learned to play from. So I keep a lot of those old guitars around, too. The guy that builds my guitars has actually just come out with a line of guitars that sound like the old guitars. Because, when I play with the Earls of Leicester, I play only old guitars, but he’s got this new guitar I played on the new record with the Earls and no one noticed.

Old sound, new technology. Probably sturdier.

Better construction, yeah. The older dobros, the Dopyera brothers got really lucky. [Laughs] The cone, a lot of things about the guitar haven’t changed since 1927. But the construction has, and how they’re big, beefy, low-ended things that have all these voices that the old dobros didn’t have. But the haunting element, for me, that drew me in in the first place, that’s missing from the big, beefy, hybrid guitars.

…

You mentioned the Earls of Leicester. I mentioned the Transatlantic Sessions and other collaborations, but your latest record is a Jerry Douglas Band joint called What If. Where do you see that album fitting into the wider landscape of your work?

That was really pushing my audience, I think. I quit a long time ago trying to make records for my audience.

I would think you would’ve had to.

I make them for me. I figure, if they really like me, they’ll go wherever I go.

Or wait until the next thing comes.

Or just wait until it comes back around to what you like! [Laughs] I love that record because it’s so big and full. It’s the full band effort with two horns and electric guitar, and everything is on this record. Except keyboards. But John Medeski is gonna play with me at MerleFest! So who knows where we go from there. But I just like the full sound and being able to, more or less, play the band, at this point. It’s dobro driven, and I write everything on the dobro, but everybody gets a little piece of the action.

…

[Tell me a memory of or something you gleaned from] Earl Scruggs.

Earl Scruggs was probably the first thing I remember hearing — ever. Then, when I got old enough, even at five years old, I knew that was good. I knew that was a good sound. It was obvious, just the way my dad would react to it and everybody, before I ever saw him. And then, when I saw him, he was on a pedestal to me, as was Josh Graves and the whole band. That was like seeing the Beatles for me, at six or seven years old, to see Flatt & Scruggs live in Youngstown, Ohio, at Stambaugh Auditorium. I even know what date it was and everything. It was like seeing the Beatles.

And then, I grow up and I move to Nashville and Earl Scruggs becomes my friend. That’s just nuts. But then, to get on the bus with him and be playing in his band, just to wind him up and let him start telling stories … because he was a very quiet man, a very quiet, reserved man. But when he got started telling stories, he couldn’t stop. It was so good! Everything was so good. Every minute, every second that I spent with him, I cherished. I’m blessed to have hung out with and been in the presence of some of these people. And Earl Scruggs is way up there on the top of the heap. There are not many people you can look at and say, “That guy is definitely a legend.” He’s like a George Washington, Abraham Lincoln kind of guy. [Laughs] I haven’t met many of those, a couple others maybe, but he was the first one — the first sound I ever heard and what influenced me in the journey that I’ve had, and what made me take the path that I took.

Well, thanks, Earl.

Thanks, Earl. Gee-whiz.

Watch all the episodes on YouTube, or download and subscribe to the Hangin’ & Sangin’ podcast and other BGS programs every week via iTunes, Spotify, Podbean, or your favorite podcast platform.

Hangin’ & Sangin’: Béla Fleck & Abigail Washburn

From the Bluegrass Situation and WMOT Roots Radio, it’s Hangin’ & Sangin’ with your host, BGS editor Kelly McCartney. Every week Hangin’ & Sangin’ offers up casual conversation and acoustic performances by some of your favorite roots artists. From bluegrass to folk, country, blues, and Americana, we stand at the intersection of modern roots music and old time traditions bringing you roots culture — redefined.

With me today in the Writers’ Rooms at the Hutton … Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn. Welcome, you guys!

Both: Hi!

Echo in the Valley, the latest duo release. It’s your second. The first one, it did okay for you. You know, you got a Grammy, whatever. My real question, what’s the body count on this record?

Abigail Washburn: How many people have died in the making of the record?

No, on the record, how many people died? Because the last one had a body count.

Béla Fleck: That’s true, and we’ve moved away from that sort of thing on the new record. And we’re talking about the murder ballads, of course! [Laughs] For anybody out there who’s really getting uncomfortable. Yeah, we didn’t go so much into the murder ballads. Though, to tell you the truth, the one song that Abby wrote, “Shotgun Blues,” it sounds terrible, but nobody actually gets hurt in it. It’s actually a very sweet situation.

I’m not sure I believe that.

BF: It’s all about a girl who’s giving a guy a good talkin’ to.

AW: At the end of a shotgun.

BF: At the end of a shotgun, but no actual creeps get knocked off in the song. But we decided to stop doing it presently anyway, just because of the current horrible things that have been happening in our country, and just to give that stuff a bit of a rest.

AW: Because it was really supposed to be kind of humorous in a way, you know.

BF: Yeah, it was a joke.

AW: I mean it was a serious response to the fact that it’s usually women who die in murder ballads. So it had a serious intention, which was to expose that and take the power back in a funny way. But right now it doesn’t feel like shotguns are funny.

That’s true.

AW: So we had trouble continuing to play that song. Which is good, anyway, because there’s all this other material on this record that we’re eager to share with you.

BF: I was thinking we could rewrite the song a bit and make it be about a slingshot, about a girl holding a slingshot on this creep and just stay there until he gets his crap together, and if he doesn’t, oh boy, he’s gonna get zonked, right in the left eyeball.

AW: That’s creative honey. We’ll work on that.

…

I’m a big fan of Krista Tippett’s and On Being, and your episode is one of my very favorites.

BF: Thank you.

The way you guys think and talk about the banjo and the history of the banjo and what that means to you, and how you carry that forward and hold that in your music — its power, its potential, all of those things — it’s just remarkable to me. It was very moving to hear you talk about it. If you had to sum up what the banjo means to you in a few words, what would it be?

BF: Well, I’ll start and you just think about something better to say than what I’m gonna say.

AW: I usually do. [Laughs]

BF: Yes, she actually does. But for me, I just love the banjo, so of course, if you love something, you look for all of the cool things about it and the things that you identify with. It’s kind of justifying a life of pursuing something you really dig. And because you spend so much time around it, you learn those things that really make it special. So I know that there are a lot of other wonderful things in the world besides the banjo, but for me, making the banjo the most important thing in my life, until I met Abby and until we had kids, and that changed the balance …

Only just a little, though. [Laughs]

BF: Yeah, it goes back and forth. But then you learn the story of the banjo, and it becomes a very noble story. You can see the history of mankind through this instrument. It’s just powerful. There are so many stories in this thing — from African roots, and even before Africa, probably in Mesopotamia, and then coming here and being this hybrid instrument that crosses between Black and white society and, eventually, crosses over completely to white society, to the point where Black folks, a lot of folks don’t even really realize the banjo came from their heritage anymore. It’s kind of confusing. So I don’t know, I love history anyway. I’m a history buff. I love reading history books, and I read a lot of books about American history, and then I ended up sort of in the middle of it falling in love with this instrument. Now it’s time for Abby to say something much better.

AW: [Laughs]

Whatcha got, Washburn?

BF: Lay it on us!

AW: I completely agree with Béla, as to all the aspects of how it’s intellectually enlightening to learn through the banjo — its history and its path and its journey through the world, and especially in American society. For me, a lot of music is very much about spirit and spirituality, and what I mean by that is, there’s a spirit that can be channeled and passed along when something like this, an object that does have so much history to it, when I pick it up and start playing it, and I can feel the stories of people before. I know Béla and I both feel that these stories people have been singing about from the past are so important because they expose how humans have been and the patterns of human behavior throughout history — their hopes, their wants, the trials and tribulations they lived through, the joys and the successes of life. It’s just so helpful to hear those old stories and recognize that humans are still basically the same. There’s comfort in that, but there’s also a calling.

And so the spirit of the banjo, its heritage, and the voices that come to me through it teach me that there’s a lot to retain and preserve from our history and our roots, but there’s also a lot to be thought about, in terms of the potential of humans to transform and change. And there are ways we really need to do that. There are mistakes and sufferings we impose on each other that the old stories tell us about — like old murder ballads is a very obvious one. Protest songs, inspirational songs … like we do a version of a song called “Come All Ye Coal Miners,” which is a woman named Sarah Ogan Gunning in Appalachia telling the people, “I’ve lost two children to starvation, both my husband and my father died of black lung. This is wrong.” And yet, this is still happening today. So we can sing the same song that was written by her 60 years ago in the mining camps, and it’s still very powerful today, and it can be a catalyst for change. So I believe music is a catalyst for change and for preservation, and all of it’s important.

BF: And also just reminding us of things. Because we make the same mistakes over and over again, as people and as a race. So if you’re cognizant of things that have happened before, you might have a better chance of avoiding some of them.

I just want to throw one weird thing out there: It just sort of struck me that the banjo was rejected by Black people because it too much embodied the slavery days. And then later, it was rejected by white people because it too much embodied white Southern culture for a lot of people, and it was put down and made a joke of. So it’s been made a joke of from both angles. It’s very ironic. And then you’ve got people from all over the world … I mean, I come from New York City, what am I doing playing the banjo? But you know, there is a lot of banjo playing from the 1800s on in New York City. So anyway, that’s my last thing to throw in on that subject.

AW: I’m just gonna dovetail on what you’re saying. It feels like a powerful time right now. There’s a lot of polarity, lots of energy going in different directions, divisiveness, people sensationalizing emotion into reality. So it feels like a time when there can be a very transformative impact from things in culture, like music. And it does feel like a new day for the banjo. And that’s global, but also very connected to roots and to our local existence, too. And I think it’s the perfect device to channel what we need, which is preservation of what’s beautiful, what’s meaningful, what defines us, and the power to change what happens in the future.

Watch all the episodes on YouTube, or download and subscribe to the Hangin’ & Sangin’ podcast and other BGS programs every week via iTunes, Spotify, Podbean, or your favorite podcast platform.

Steve Martin: Making the Same Sound Different

The sound of a five-string banjo has a cosmic pull. When Earl Scruggs first took to the Grand Ole Opry stage with Bill Monroe and his Blue Grass Boys in 1945, his rapid-fire, three-finger picking style shocked and stunned the Ryman Auditorium audience and radio listeners across the country. The standing ovation he received shook the entire building to its rafters with hands clapping, boots stomping, and hootin’ and hollerin’. It was the Big Bang of bluegrass banjo.

Almost every banjo player could tell you the first time they heard the instrument, the first time they encountered its cosmic pull — a personal, introspective banjo Big Bang unique to each person who is struck by its irresistible, joyful, magnetic sound. Steve Martin describes the first time he heard a banjo as his “What’s that!?” moment. “I kind of pin it on the Kingston Trio,” he remembers. “But I know there were earlier things. I fell in love with the four-string banjo, too. When I was 11, I would go to Disneyland to see the Golden Horseshoe Revue, and there was a four-string banjo player. When I worked at Knott’s Berry Farm, there was a four-string banjo player there, too.” His voice shifts to a whisper, as he adds, “But, we all know that five is better.”

He continues, “I do believe it was kind of the Kingston Trio or folk music, in general, that really made the sound like, ‘Wow, what a happy, wonderful sound!’”

He picked up the banjo as a teenager, taking on three-finger, Scruggs-style picking with the help and influence of his friend John McEuen. But, unlike most banjo pickers, who choose one style — Scruggs’ namesake method, or jazz and ragtime on tenor and plectrum banjos, or any of several types of frailing — Martin also had a “What’s that!?” moment with the old-time form, clawhammer: “It was a record called 5-String Banjo Greats and another record called the Old-Time Banjo Project. They were both compilations. So I don’t know who introduced me to clawhammer. When I was learning three-finger and I was into it about three years, I started to really notice clawhammer, and I go, ‘Oh, no. I have to learn that, too.’”

He is a master of both three-finger and clawhammer to this day and, on his brand new record, The Long-Awaited Album, he shifts effortlessly between the two — sometimes within one song.

Through his career as a comedian and actor, the banjo was ever at Martin’s side. It was a part of his stand-up act, it was peppered into his comedy albums, and it made cameos on his TV appearances. It would be cliché to assume that the banjo and bluegrass were a byproduct of Martin’s comedy career, but the instrument was never an afterthought, an addendum, or a prop. In fact, bluegrass and folk music showed him from his early show biz days working at theme parks that humor was an integral part of these musical traditions.

“When I first started hearing live music, like the Dillards or folk music of some kind, they all did jokes,” he says. “They all did funny intros to songs. They did riffs. They did bits. And then they did their music. That’s essentially what we’re doing now.” The silly, whimsical, comedic elements of the music Martin makes with his collaborators, friends, and backing band — the Steep Canyon Rangers — are just as much a testament to Martin’s history with bluegrass as they are a testament to his extraordinary comedy career.

During the seven years that elapsed between their last bluegrass album, Rare Bird Alert, and The Long-Awaited Album, Martin and the Rangers wrote, developed, and arranged the project’s material during soundchecks, band rehearsals, and downtime on the bus. Barn-burning, Scruggs-style tunes and contemplative, frailing instrumentals are sprinkled amidst love songs and story songs, silly and earnest, all steeped in quirky, humorous inventiveness. The album is centered on a solidly bluegrass aesthetic — but bluegrass is not a default setting.

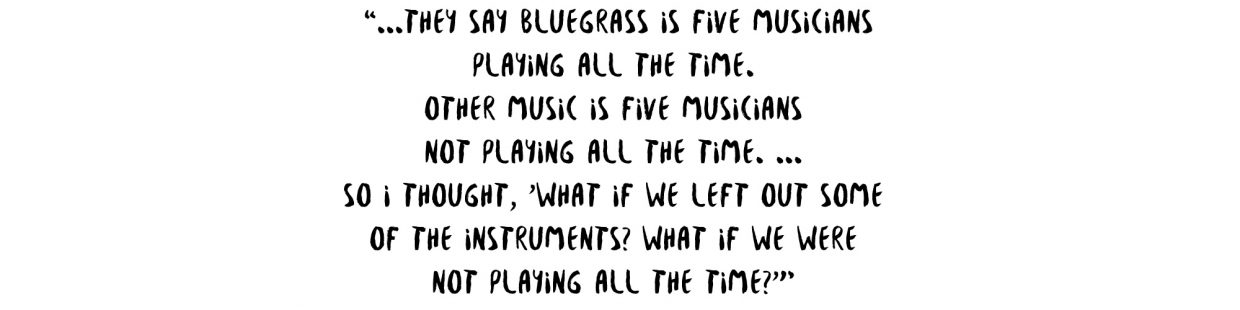

Musical and production choices for each song were pointed and deliberate, with producer Peter Asher, Martin, and the Rangers keeping each song central and building out the sound around any given track’s core idea. “I love the sound of the five, six instruments that are traditionally bluegrass,” Martin clarifies. “That’s all we need. The Rangers, they say bluegrass is five musicians playing all the time. Other music is five musicians not playing all the time. In bluegrass, they have breaks, but there’s always the backup going. There’s always everybody chopping. So I thought, ‘What if we left out some of the instruments? What if we were not playing all the time?’ It really made a different sound.”

By leaving out an instrument here or there, adding in a cello or, in the case of the lead track, “Santa Fe,” an entire Mariachi band, the album’s sound registers immediately as bluegrass, but refuses to be lazily or automatically categorized as such. First and foremost, it sounds like Steve Martin and the Steep Canyon Rangers. “I’ve always loved the idea of the sound of the banjo against the cello, or viola, or violin, because you have the staccato notes against the long notes. The cello or viola contribute to the melancholy and mood of the banjo. But mostly, it’s just us, the seven musicians, including myself. We can reproduce it on stage … except for the mariachi. But the song called for a mariachi band, you know?” He laughs and adds, “There’s almost no way to avoid it.”

Where many bluegrass and folk writers eschew modern vernacular, places, and topics, Martin leans in, embracing contemporary scenarios and themes that don’t necessarily fit the stereotypes of train-hopping, moonshine-running, field-plowing folk music. The Olive Garden, nights in a biology laboratory, a gate at an airport, “Angeline the Barista” … the timelessness of roots and folk music isn’t lost in these themes and settings; it’s enhanced, it’s relatable, and it’s damn funny.

“I’ve written a song about a train, and I’ve written a song about Paul Revere. I think it’s got to be specific for people. They’ve got to go, ‘I know that!’ If I’m writing about a train, I know that 99 percent of people that the song will be heard by won’t really have that experience. But if I write about the Olive Garden and a girl busting up with you, I think a lot of people can relate to that, even if they don’t have that exact experience.”

The relatability and visibility of Martin’s music have brought bluegrass — and the banjo — to countless ears that may have never heard it otherwise. In 2015, the International Bluegrass Music Association awarded Martin a Distinguished Achievement Award with this visibility and outreach in mind. With The Long-Awaited Album; the Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass that he awards annually; a national tour of his banjo-forward, Tony-nominated Broadway musical, Bright Star; and a heavy touring schedule criss-crossing the country with the Steep Canyon Rangers and his longtime comedy partner, Martin Short, Martin is poised to continue bringing the banjo to many first-time listeners.

But when faced with the idea that he, himself, could very well be the “What’s that?!” moment for an entire generation of brand new banjo players, he is unfalteringly modest. “What I try to express with the banjo is the sound of the banjo. When I first heard Earl Scruggs, I loved his skill, his timing, and his musicianship. I regard myself as someone who’s expressing the sound of the banjo rather than being a superior, technical player like Béla Fleck. So, if anyone picks up the banjo from hearing me, it’s because they fell in love with the sound of the banjo. What I do is get the sound of the banjo out there to a broader world, I guess.”

Lede illustration by Cat Ferraz.

3×3: Violet Bell on Prince, Prince, and Prince

Artist: Violet Bell

Latest Album: Dream the Wheel

Personal Nicknames: “Omar” is ripe for situation-specific nicknames — Showmar on stage, Promar when we’re practicing, Gomar when we’re on the road … the list goes on. Omar’s been introducing Lizzy on stage as the boss with the sauce, Lizzy Ross. Sometimes she also has floss.

What song do you wish you had written?

Omar: “7” by Prince and the NPG, or “Agua” by Jarabe de Palo

Lizzy: This is a tough question. Today, the answer is … “I Was an Oak Tree” by Jonathan Byrd. Omar played with JByrd for a few years, and we both admire his catalog of gorgeous, soulful songs.

Who would be in your dream songwriter round?

Neil Young, Debussy, Nina Simone, JJ Cale, Fela Kuti, Gillian Welch, Lou Reed, Béla Fleck … how many songwriters can we have? The list goes on! Prince! Dolly!

If you could only listen to one artist’s discography for the rest of your life, whose would you choose?

Prince, Prince, Prince. So many different flavors, concepts, and motivations. We love that man’s willingness to go out there into uncharted musical and conceptual territories and bring back some light. Or Béla Fleck. His discography runs the gamut of styles and he’s got music for every emotion.

How often do you do laundry?

We’ve gotten better about it! About once a week now for the both of us! Any longer and the car can get …gnarly. Folding it is the real challenge. As we tour more, what’s the point of having more clothes than we can fit in a duffel bag?

What was the last movie that you really loved?

We both loved Secret of Kells — spectacular Irish music, faeries, ancient secrets buried in dusty old books? Yes, please. Omar loved Hateful Eight. Tarantino films are always full of surprises and nuggets.

If you could re-live one year of your life, which would it be and why?

Lizzy: Maybe next year? I’m excited to find out. It seems the best is yet to come. I have loved being alive, so far, and I’m excited to be here and now. Life keeps unfolding before us, and I wouldn’t change where it has brought me so far!

Omar: Pass.

What’s your go-to comfort food?

We LOVE Pho. On the road, however, all those noodles can make us sleepy behind the wheel. Green curry is a serious contender. On tour, we sometimes eat it every day… sometimes more than once a day! We like the spice. We’re beginning to wonder if we need a green curry intervention.

Kombucha — love it or hate it?

Love it! Fizzy mushroom tea?? Count us in! Before we got so busy touring, we used to make it at home!

Mustard or mayo?

Both! They’re like us: complementary.

Béla Fleck & Abigail Washburn, ‘If I Could Talk to a Younger Me’

It’s good to be reminded, sometimes, of the important things — the ones we so easily forget. Between the breakfast coffee and the toothbrush before bed, a day can swing by in what seems shorter than a few breaths. It’s a cliché thing that, most memorably, we once needed Ferris Bueller to cement into our brains: “Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.” Pop culture has a way of being pretty poignant. Preach, Ferris.

Abigail Washburn and Béla Fleck, two of our modern masters of the banjo who happen to also be married with a child, handle this concept of the fast drip of time more elegantly on “If I Could Talk to a Younger Me,” from their forthcoming LP, Echo in the Valley. Emotive and ethereal, Washburn sends a message out into the universe … to her self, to her offspring, to whomever might tune their ear to her songs. “If I could talk to a younger me, I’d tell me to go slow,” she sings, as the banjo plucks furiously in an instrumental duet. “This time on earth, it moves so fast, and when it’s gone, it’s gone.” These aren’t complicated lyrics cased in metaphor, but a rather simple reminder to take a moment — as Ferris would say — to stop and look around once in a while. And it never hurts, especially if you’re Washburn and Fleck, to do this in a way that makes that time on earth sound just a little bit more beautiful.

Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn to Host the 2017 IBMA Awards

Banjoists Béla Fleck and Abigail Washburn are set to the host the International Bluegrass Music Association awards in September. Their presence on stage signals the genre’s expansive growth in recent years, reaching toward the edges in order to better understand the center. It also preempts their second full-length album, Echo in the Valley, due out October 6 on Rounder Records. The follow-up to their 2014 self-titled debut finds the husband-and-wife duo exploring new territory by restricting their creative path: They only used banjos on their latest set of songs, and ensured all recordings could be reproduced live. The resulting conversations they have — a mix of original songs (all co-written for the first time in their career as a duo) and covers of Clarence Ashley and Sarah Ogan Gunning — reveal a quiet muscularity. The limitations, rather than stripping away their imaginative prowess, instead lay fecund ground. If 2017 really is the “Year of the Banjo,” then Béla and Abby are its exciting exemplars, showcasing just how much fun can be had on the edge.

The IBMAs are part of the International Bluegrass Music Association, and will take place in Raleigh, North Carolina, on September 28. Tickets can be purchased through the IBMA website.

As a superstar banjo couple, do you have a conjoined nickname like Brangelina?

Béla Fleck: Abba.

I think that one’s already taken.

Abigail Washburn: I don’t think we create those ourselves. You’re going to have to create them.

Leave it to the people — that’s fair. What does it mean to you both that you’re hosting the IBMAs together?

Béla: I’m quite proud. I’ve had a long association with the IBMAs — from the first year when I won the banjo award, then a couple of years ago I did the keynote. For me, as a long-time bluegrass player and a person in that world, I’ve been a little disassociated, and this means I’m not anymore. I’m right in the center of it.

Abby: And for me, it’s an extreme honor. I’ve played music that’s certainly got a lot of bluegrass elements to it — the old-time Appalachian music that I’ve been playing with Uncle Earl for a long time, and the work that Béla and I do — so just to be so deeply included in the community, but also to be on stage in front of those wonderful people who are preserving and passing along this really bright and beautiful piece of American culture and tradition. I’m excited, too, because Béla and I and the folks that are heading up the awards presentation, are brainstorming lots of ideas to be playful and have fun. We’re excited to get to share the playfulness of our couplehood on stage.

Béla: I think we both look for ways to be creative with any situation that we’re involved in. We’re trying to figure out, “Okay, what could we do that would really be fun and really feel good to everybody?” We’ll see what we come with.

It seems like a crowd that appreciates laughter.

Béla: I think part of that is they’re all together. It’s very safe for bluegrass people. Out in life, we can sometimes feel we’re very unusual and odd, but at IBMA, everyone’s together and so everyone understands these subtle jokes about old-time bluegrass people we all love … or Sam Bush’s hair. I think that’s really special.

I know, like any genre, there are some players who get mired down in tradition and don’t want to see things change, but you’ve both pushed those boundaries in really exciting ways.

Béla: I would just say the very fact that we’ve been invited to do it … because I’ve spent a lot of my life outside of the bluegrass world playing other kinds of music, but I always take bluegrass with me. And Abby, you wouldn’t call her a bluegrass artist at her core, but she’s very associated with it. It’s showing that we’re all part of that family. We’re very respectful of the tradition; we just happen to live on the edge of it. But bluegrass is a very wide musical genre these days. We only lose by chopping off the edges. Even Earl Scruggs was excited about swing. I’m hopeful that this is just part of appreciating the fact that you need some outside blood every once in a while. Where would we be without “Polka on the Banjo”?

That’s what makes for such exciting growth. Well, BGS has dubbed 2017 “The Year of the Banjo” because there are so many projects that are either banjo-focused or banjo-inspired. What would you pin to that explosion?

Béla: I’m a little skeptical of those kinds of things. I think people are doing great work every year and, a lot of times, the great strides come gradually along the whole scope of the curve, but then, every once in a while, there’s a moment when everybody shows up at the same time with new stuff and we do make a big jump. In the past, some pretty wonderful things were happening in the dark that might not even be covered, and might be ignored by the world at large, but now there’s enough interest in the banjo that we can really talk about it and build some energy around it.

Going back to your keynote address from 2014, you mentioned how the banjo was almost a hindrance to your early career because of the way people viewed it. It’s gone through its own sea change in terms of popularity.

Béla: I think part of it is we aged away from Deliverance. It’s an old movie and you have to go find it now. When it came out, it was everywhere and the song “Dueling Banjos” was such a huge hit. It sort of cemented that image of what happened in the movie with how people thought about the banjo, which was an unfortunate piece of that whole phenomenon. I saw very gradually a shift from “Squeal like a pig” to “The banjo? That’s cool.”

Abby: I think there have been a lot of people working really hard for a long time, including yourself. I will compliment my husband, at this point. He’s been working for decades trying to show another side of the banjo to people. Now there are a lot of younger groups who have really taken to it because of Béla.

Béla: Well, a lot of other people, too.

Abby: The list goes on. It’s having an impact. The things that younger people see isn’t Deliverance, but the Bill Keiths and the Rhiannon Giddens, and, gosh, Mumford and Sons. Different kinds of people playing the banjo. There’s the most wonderful representation of banjo that’s come from the edges. It’s very cool.

Very much so. Turning to your forthcoming album, you set out limitations about what instruments you could use and recorded songs that could be recreated exactly on stage. Why set such staunch parameters around creating?

Abby: Limitations are actually extremely freeing, when you set the right ones. We really like being able to create a record that can be experienced live by people. And it’s created these new kinds of challenges for us, because we want to learn and grow and spread our wings as a duo, and working on the eccentricities and complexities to develop the nuance of duo performance means that we incorporated some new ideas into what we’re doing.

Béla: My only addition to what Abby said is that it’s awkward when you make a record that you can’t perform live. We wanted the honesty of the music to be very clear. It’s really very sparse duet music, but we’re finding a way to make it sound as big and powerful as we can with just our two instruments. It’s an art of recording that we aspire to do well at, because I love that part of the process myself. I’m a nerd recording-type guy.

I would say that this latest LP is quieter than your debut and yet it’s no less powerful. I kept thinking of musical conversations that ebb and flow so naturally. Has your playing bolstered other forms of communication between you two?

Béla: I would say we have suffered times on this record because we have a lot of stuff to figure out.

Abby: Suffered times, in terms of the fact that we had an infant. This time, we had higher expectations for ourselves, musically, so we took on new challenges that made for a lot of conflict at times.

Béla: Someone would have an idea, and rather than the other person going, “Yes, that’s perfect,” they’d say, “That’s cool, what if we tried this?” You might get your feelings hurt a little bit, but a little time would go by and we’d come back and go, “Okay, how can this be both of us contributing equally to the song?” I think we’re really good in our relationship at taking each other into account, but in the creative process, things are never exactly equal. You gotta fight for your ideas and then you have to find a way to change them to fit what the other person wants.

Abby: We decided we wanted to write the lyrics together, and that was different from the last record.

Béla: So that was hard for both of us, but we got to a place where we’re both very pleased, and that made our relationship stronger.

Photo credit: Jim McGuire

Béla Fleck on Playing His Newest Role

Béla Fleck has explored chapter and verse over the course of his tome-length music career, but there remained one role he had yet to play — father. The world’s most inventive banjo player took on that title over three years ago when he and his wife, clawhammer banjo player Abigail Washburn, welcomed their son Juno. Parenthood inevitably shifted innumerable things for both musicians, not least of which included when and how to write music. “It’s all family-motivated,” Fleck explains about his life now. “How do you find the time to be a musician when you’re trying to be the best parent you can be? It was a new structure that I’ve never experienced before.”

It was especially tough at first. Fleck and Washburn received a standard warning from their doctor about Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) prior to taking Juno home from the hospital, which left an indelible mark. “All I could think was, ’I’m not letting him out of my sight. I’m going to have my eyes on him 24/7,’” Fleck recounts. “When he slept, I would sit and watch him all night because we were all so spooked.” Composing at home, as opposed to concentrating on duet or band projects requiring his presence elsewhere, became a way to balance fatherhood with the musical identity he’d long inhabited. “That was the beginning of realizing you can get a lot of work done by yourself when you’re with your family,” he says. Fleck took to using naptime and nighttime to work out ideas he quickly captured on a recorder during other points of his day. “Creativity can be like maple sap coming out of a tree,” he says. “If you don’t collect it for a while, and you go back, there’s a whole bunch waiting for you. It really happens that way sometimes.” As a result of his newfound approach, Juno’s influence is everywhere. “Anybody who has kids knows how that works.”

It’s an influence that extends to Fleck’s latest project and second banjo concerto, Juno Concerto. Besides naming the project after his son, Juno’s thumbprint arises thematically throughout each of the three movements. “As a musician, I was trying to be who I was as a father, and I also wanted the music to express some of the ways I was feeling,” Fleck explains. “Some simpler emotions were coming out that I was not expecting to ever feel before I became a parent. I felt more comfortable with letting them be in the music and encouraging them, while still finding ways to be my complicated self in the middle of it.” The end result is cinematically striking, full of sweeping musical phrases and a seamless conversation between banjo and orchestra. “I didn’t expect to be playing over the full orchestra going crazy, but I had to be very aware of creating textures where the banjo could be heard and then creating places where I was either in support of the orchestra or not playing at all so I could be big and not distracting from the orchestra,” he says. “It’s like a David and Goliath heroic kind of thing, but they’re not competing. At their best, they lift each other up.”

If there’s one singular characteristic to Fleck’s career, it’s his willingness — his inclination — to push boundaries. Having recorded as a solo artist, a collaborative partner, and in an array of bands — including the Béla Fleck and the Flecktones — as well as a variety of styles, Fleck takes pleasure in erasing preconceived notions about where his instrument belongs. “I want it to be on the edge and something that hasn’t been done before,” he says about his approach. “That’s the whole reason to play music: expression and exploration.” Thanks to his boldness, Fleck has done much to quell ideas about high and low art. The banjo may have found its most familiar setting in bluegrass, but over the course of his career, Fleck has helped reveal its historical place in early jazz (bringing it up to speed in the modern era), its African lineage, and now its classical possibilities. “I’d prefer to be a wine that matured and got better than a wine that you need to drink when it’s young, because I’m not young anymore,” he laughs. “I’m trying to say something meaningful and trying to get deeper into honest, pure expression as I play music, whatever music I’m playing.”

Fleck composed his first banjo concerto in 2011 after receiving a commission from the Nashville Symphony Orchestra. “It’s a lot of fun when you’re composing. You’re just sort of ordering everyone around on paper,” he says. Appropriately titled The Impostor, it involved a good deal of posturing; Fleck concentrated — thematically and literally — in asserting the banjo’s place alongside more traditional classical instruments. But he didn’t include a true slow piece for the banjo, following a concerto’s typical fast-slow-fast structure. With Juno Concerto, he set out to answer that challenge. “The banjo tends to do things well that are fast and crisp and clear,” he says. “I made a real point of insisting that the banjo could play slow, as hard as it was to do these gaping spaces. It was a challenge.”

Juno Concerto didn’t fill an entire album’s worth of space, so — as he’d done with The Impostor — Fleck set about adding additional string pieces, recording “Griff” and “Quintet for Banjo and Strings: Movement II” with string quartet Brooklyn Rider. He originally composed “Quintet for Banjo and Strings” with Edgar Meyer in the early 1980s, but never got about to recording it. “It’s so good to have something like that to settle the dust of all the craziness of the pieces I like to write,” he says. And since he’s received one more commission to compose a concerto, he anticipates following suit by combining concerto and string pieces for that next album. “I didn’t intend to do the exact same thing, but then I started to think, ‘Well, if I do it three times, it’ll be a set,’” he says. “Three concertos with three string pieces, that becomes interesting.”

For all his experimentation, it might seem that nothing intimidates Fleck anymore. In fact, the bravery he’s developed by inserting himself into myriad musical conversations only comes about after months and months of hard work. “I’ve done so much stuff that, sometimes, I forget how hard I worked on each thing,” he says. “I have a pretty intense work ethic, and then when I’m done, I forget and I go back and listen to the record and go, ‘Oh that sounds pretty good.’ I don’t hear all the blood and guts that went into getting it to that level. But when I start on a new project, I go, ‘Wow, this doesn’t sound very good. Maybe I just don’t have it anymore. Maybe my good years are behind me.’ But I don’t realize that I spent months and months and months working on those projects that, in hindsight, makes them sound easy.”

If there are ever any doubts about his talent diminishing with age, Fleck’s work ethic seems likely to keep things in check, as well as his son. Growing up in a household with two world-renowned musicians means Juno has developed quite the ear. “He doesn’t realize how much he knows about music from being around it so much,” Fleck says. Still, there’s one point on which they continue to disagree. “He always asks me, when I play instrumental songs, ‘When’s the singing going to come in?’” Fleck jokes. “That kind of bothers me because I’ve made a life of trying to make believe that singing doesn’t have to be there for music to be good. I’ll play him a song and he’ll go, ‘Papa, that’s too long.’”

Lede illustration by Cat Ferraz.

Don’t Miss PROJECT AMERICANA at Symphony Space in October!

3×3: Hot Buttered Rum on Doc Ellis, Béla Fleck, and the Perils of Hydration

Artist: Nat Keefe (of Hot Buttered Rum)

Hometown: Redwood City, CA (currently lives in San Francisco)

Latest Album: The Kite & the Key

Rejected Band Names: Shuttlecock, Christmas Is Ruined, Webalo … I think we’ll stick with Hot Buttered Rum.

If you had to live the life of a character in a song, which song would you choose?

If I could be a character for one day, I’d like to be Doc Ellis in Todd Snider’s “America’s Favorite Pastime.” That guy pitched a no-hitter for the Pittsburg Pirates high on acid! What’s a stranger thrill than that?!

Where would you most like to live or visit that you haven't yet?

I was driven by travel-lust for years. Now that I’ve been to five continents and all the states, all I want is to explore my home. That is, when I’m not enjoying the highways and motels of this great country with Hot Buttered Rum.

What was the last thing that made you really mad?

…

What's the best concert you've ever attended?

The month I graduated high school, I saw Béla Fleck at the Fillmore. Something came together for me there, and I saw a life of music unfold in front of me. Seven years later, I was onstage with Béla in Bean Blossom, Indiana, for Peter Rowan’s all-star jam! I love that guy’s spirit of adventure and dedication to excellence. He makes me think, “What’s the next uncomfortable, scary situation I’m going to put myself into?"

What was your favorite grade in school?

A split between kindergarten, because I love finger-painting, and senior year, because that’s when my game with the ladies started coming together.

What are you reading right now?

I just finished Ralph Stanley’s autobiography in preparation for this project. Highly recommended! He somehow got his voice onto the page, and I don’t think he blogs every week for practice. I’m also on a serious Philip Roth kick. I think part of me wishes I was Jewish and from Newark.

Whiskey, water, or wine?

A little of each, please. I have aspirations to be well-hydrated, but I also have a small bladder. So I balance my water intake with our travel itinerary. I get made fun of for always having to pee. My skills with a culca have improved. What’s a culca, you ask? Well …

North or South?

Wherever I’ve travelled in the world, there’s always a rivalry between the North and South, the East and West, the highlands and lowlands. People, myself included, thrive on rivalry and calling someone the “other.” I channel this urge into professional baseball. Go Giants! Beat L.A.!

Pizza or tacos?

I live in the Mission in San Francisco. It’s all about the burrito.