It’s no secret that the South is home to some of the greatest musicians around, past and present. From early bluesmen like Robert Johnson to country legends like Hank Williams, the South has produced some of the foremost forebears to our current musical culture. And while the South has big names a-plenty, it’s also rich with local musicians hoping to keep the region’s musical history alive, often, unfortunately, doing so with little to no recognition.

The Music Maker Relief Foundation was established for that very reason: to, in its own words, “preserve the musical traditions of the South by directly supporting the musicians who make it, ensuring their voices will not be silenced by poverty and time.” Founded in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in 1994, the 501(c)3 non-profit has grown from a handful of passionate music lovers helping a small coalition of local musicians with simple necessities like securing food and paying bills to a globally recognized entity responsible for working with over 300 artists, releasing more than 150 albums, and spreading Southern music to all corners of the world.

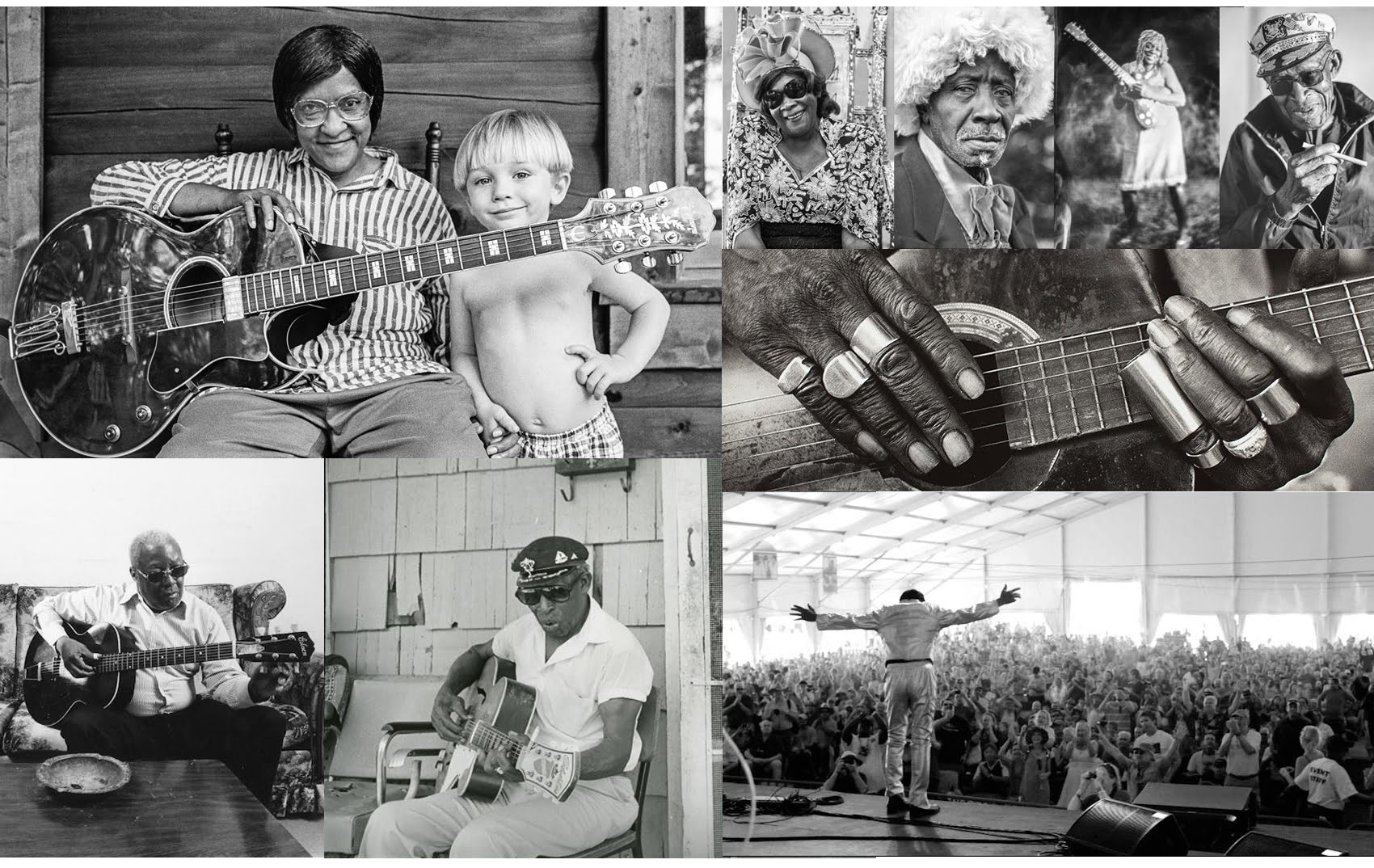

Timothy Duffy co-founded Music Maker with his wife Denise after enrolling in the folklore program at UNC, Chapel Hill. His time working in UNC’s archives led to a chance meeting that planted the seeds for what would become Music Maker. “There aren’t many jobs in folklore,” Duffy laughs. “I was working for the archive and met an old bluesman named James ‘Guitar Slim’ Stephens in Greensboro. Before he passed, he introduced me to a guy named Guitar Gabriel in the early ‘90s. Gabe and I became partners and we put out a cassette. He was a great blues artist. He was very famous in a circuit that was never documented by white folks. It was called the Black Carnival Circuit. So he knew everybody. He knew all the musicians because he’d played in their towns for 40 years.”

Through his time with Guitar Gabriel, Duffy realized there was a vast community of phenomenally talented blues musicians that was virtually unknown to the rest of the world. Even more troubling to Duffy was how many of these musicians were living in poverty. “I soon realized that there was no place for these guys in the music business,” he says. “The blues guys never sold many records. They could barely scratch by a living. You’ve got B.B. King and that’s it. If anyone knows a blues artist after B.B., that’s amazing.”

The contrast Duffy’s own experience encountering countless talented players with the widely held notion that the blues was a dying art appealed to his presevationist roots. “There was this really weird view that the blues was dead,” he explains. “That was clear to me after meeting people like Alan Lomax, Archie Green, and some of the greatest folklorists of our time. It was just another case of politics of culture, of people appropriating what they wanted and keeping it for themselves and putting the culture down.”

Duffy saw the work of these little-known musicians as essential to preserving the musical legacy of the South and worked with Guitar Gabriel, Willa Mae Buckner, Preston Fulp, Mr. Q, Macavine Hayes, and a number of other North Carolina blues players to start Music Maker. A large focus of the organization’s initial efforts was simply providing these musicians with the financial assistance they needed to keep playing. “They were very disenfranchised economically. They were living on $3,000 or $4,000 a year,” he says. “We bought cases and cases of Ensure, because a lot of these guys had strictures in their throats, had nutrition problems. We bought clothes, shoes. We paid electric bills. That’s what it was founded as, at first.”

Thanks to the group’s passion, it didn’t take too long for Music Maker to begin growing into the internationally respected organization it is today. Word spread throughout the blues community that Duffy and his team were doing good work, and the community rallied around them. “Taj Mahal heard about me in 1995,” Duffy says. “I flew out to L.A. and hung out with him, and he introduced me to B.B. King. B.B. fell in love with the project and took me around London, New York, L.A., and introduced me to all of these influential people like the Rolling Stones, Dan Aykroyd — wonderful people that supported the organization. That was our start. Now we’re here, 22 years later, and we’ve issued over 300 records.”

That increased notoriety for Music Maker has, as Duffy and his team hoped, also brought newfound fame and success for the artists involved. “A lot of times, in these small communities, that elevates them greatly,” Duffy says of Music Maker’s artists. “They go from this obscure guy that lives in an old trailer, now, to an international figure in their community that has played Carnegie Hall, Lincoln Center, traveled all to Australia, France, Argentina. That elevates interest of the music and it helps them in their mission to keep this music alive and vibrant in their communities.”

While Music Maker has been an invaluable resource for older blues musicians like Ironing Board Sam and Pat Wilder, it’s also played an integral role in developing the careers of a number of emerging and newly established roots artists. Newer artists Music Maker has worked with include Dom Flemons, Spencer Branch, Cary Morin, and, perhaps most famously, the Carolina Chocolate Drops. “When I learned that the Carolina Chocolate Drops were learning from Joe Thompson, an old banjo player from right down the road, I went and saw the performance,” Duffy says. “We took this small, fledgling group that barely knew how to play instruments to a Grammy-winning phenomenon, that really did quite well.”

In addition to artist advocacy, Music Maker has kept busy over the years with all kinds of projects, including a photgraphy exhibit (“Our Living Past”), a book and CD (We Are the Music Makers), and the Music Maker Blues Revue, a touring group that has recently played as part of Globalfest at New York’s Webster Hall. “Gabe and I started [the revue] back in the early ‘90s,” Duffy says. “When we go play Lincoln Center or jazz festivals, we bring all these guys on stage and do a revue show. That cast is ever-changing as people pass away.”

Upcoming projects include a fundraiser to purchase instruments for the town’s prison bluegrass band and a new blues club set to open at the Durham Bulls Athletic Park, the latter of which has support from Durham Bulls owner Michael Goodman and his family. “They started a new brewery called Bull Durham Beer,” Duffy explains. “Right by the box office, they’re opening a blues club. For every beer that you buy there at the taproom, they’re giving Music Maker a dollar and also providing a budget for us to hire Music Maker acts. I think it’s going to be the nation’s greatest blues club because it’s one of the only places you’ll see these kind of guys playing. “

It sounds like a lot, but the folks at Music Maker see their work as a labor of love — one inspired by their deep admiration for Southern music history and the musicians sacrificing it all to keep that history alive.

“All music is from the South,” Duffy says. “All modern music. There’s not one popular form of music that doesn’t trace its roots back squarely to the South. The blues, bluegrass, pop music … it’s America’s greatest legacy to the world. It’s better than the Colt .45 or whatever guns we invented. The music is the greatest thing we’ve done.”

Lede photo of Eddie Tigner by Tim Duffy