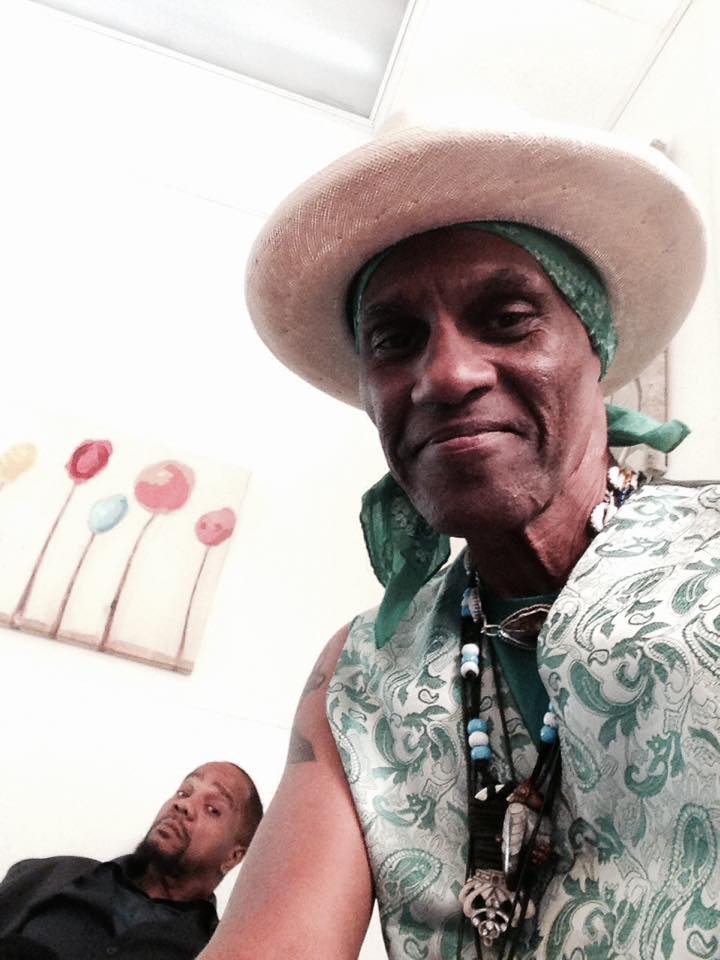

Simply put, Jimmy “Duck” Holmes is a living legend. As the last of the Bentonia bluesmen taught by Henry Stuckey, he is carrying the torch for this much-beloved rural blues tradition. Holmes was born in 1947, and his parents owned and operated the legendary Blue Front Café. The oldest still-operating juke joint, it is considered the birthplace of Bentonia Blues. Skip James and Jack Owens popularized these dark acoustic blues. Holmes took over the Blue Front Café from his parents in 1970 and has been busy spreading the music ever since. He’s pushing 69 years old and showing no signs of slowing down. On June 17, he is releasing his latest album, It Is What It Is.

Congratulations on your upcoming release, It Is What It Is. I want to ask specifically about the first song, “Buddy Brown.” It has a much harder and distorted sound than you are usually associated with. What brought about this change and did recording at your Blue Front Café affect how you approached these recordings and the overall sound?

Recording at the Blue Front Café was normal to me. I’ve been around the Blue Front Café my whole life. My parents started it when I was only 1, but I’ve been skipper of the ship for the last 46 years. It’s where I learned to play and where the Bentonia Blues grew. I’ve recorded here before. As far as that particular song, I wanted to play a song to show what I had learned from Tommy West. He lived in Bentonia, but he played hill country blues. So I played a little hill country blues in the Bentonia style.

Your vocals sound amazing on these tracks. How do you keep it in such good shape?

I don’t know. It just comes natural, I guess. I would say I get my singing from my mama. She used to sing gospel songs when she was cooking and things.

Seeing as you and your siblings spent much of your childhood at the Blue Front Café, did it operate as a juke joint from the beginning or did the live music come along later? Have the blues always been a part of your life?

I’ve been around the blues all my life. I couldn’t necessarily go into the Blue Front when I was a kid, but I was around it for as far back as I can remember. Now, historians who keep track of these things say that the Blue Front Café is the oldest surviving juke joint in the state of Mississippi. It’s never been closed. Back in the day, there were also juke houses. Jack Owens had a juke house for a long time. I believe Skip James had one for a short time. But the Blue Front Café has been a juke joint from the start.

Let’s go back to the beginning, when did you start playing music?

The first guitar I picked up belonged to Henry Stuckey. It was around 1957, but I didn’t play too much then. I didn’t start playing in earnest until the early 1970s.

I’ve read that you were the last person taught by Henry Stuckey. He has taken on a mythical status over the years. My understanding is that he served in the military and learned the open E-minor tuning from Bahamian solders. When he came back to the States, he was almost like Johnny Appleseed, but he was spreading this new guitar technique and sound instead of seeds and trees. What was your relationship like with Stuckey? Was it a formal tutelage?

I didn’t have any formal lessons from Henry Stuckey. He lived in the original Blue Front Café after my parents moved it into town in the early 1950s. He would sit on the back porch and play guitar, and I would play and carry on in the yard, when I wasn’t working. I would sit and listen to him play. That planted the seed in my mind and put that sound in my ear. Like I said, I picked up his guitar and messed around some playing.

I’ve read that you were friends with Jack Owens and Bud Spires. Did they have any advice or help out when you were starting? Was there anyone else that took you under their wing?

How much time do you have? Jack is the man! Jack, Bud, Cornelius Bright, Tommy West, Cleo Pullum, and others would come to the Blue Front Café to hang out and listen to each other play. I guess you could say that I sort of got drafted into it. Jack realized that there weren’t many younger players of the Bentonia blues and he wanted to keep it going. He understood the music better than anyone, but he couldn’t tell me to play an A or E or whatever. But he was determined for me to learn how to play.

We would sit there and he would tell me, “Watch my hands.” He would play and then want me to do what he just did. We’d spend many days at the Blue Front Café doing just that — watching his hands. Watching Bud and Jack play also helped me learn to play the harp. I can’t play it like Bud could, because no one could, but I play a little harp on my new record. The other guy who taught me to play was Tommy West. He was a hill country blues player and helped me learn how to use the low E as a bass string. He could play with the best of them.

Are there any younger acts that you enjoy?

Other than a handful of guys like Bobby Rush, Leo “Bud” Welch, Gip Gipson, Little Freddie King, Big George Brock, and a few others, most everyone else is younger! I like a lot of blues. I enjoy blues musicians who genuinely love the music. I like to invite people to play at the Bentonia Blues Festival. This year, from June 13 through June 17, we’ll have music at the Blue Front Café every evening. Then, on Saturday, June 18, we have the main day of the festival out at my farm just north of Bentonia. It’s an all-day event with real country blues from Bill Abel and Cadillac John Noland, Randy Cohen, McKinney Williams, Lightnin' Malcolm, Leo, Roosevelt Roberts, Wes Lee, David Raye, and the Blues Doctors. We also got Mike Munson and Dave Hundreiser from Minnesota and Tito Deler from New York. It’s going to be a great festival. These guys can play.

Are you working directly with any younger artists?

I’m not rushing him, but I’ve been teaching my grandson, EJ Fox, how to play in the Bentonia style. I’ve shown lots of people a few things here and there over the years. Chris Bradshaw from Bentonia is good. Jack taught my nephew, Larry Allen, a few things, but hasn’t played in years. He’s been coming by the Blue Front Café to play, and I’ve been helping him remember what Jack had taught him.

Do you have any advice or words of wisdom for up and coming musicians?

Pertaining to old-school blues, for it to continue, someone needs to learn it. You don’t have to love it, but you need to appreciate the blues as a foundation. You can’t do much on the guitar without learning some blues licks. Now, you have to practice every day. And you need to develop your own signature sound so that way people will know it’s you when they hear it.

Photo credit: Lou Bopp