When last the world heard from Hayes Carll, he was stomping and hollering his way through 2011's KMAG YOYO (& Other American Stories). But five years can change a man. Hell, five minutes can change a man who has the heart of a poet that Carll does. That's why, on his new Lovers and Leavers release, he eschews the pomp and circumstance of records past. In their stead, he and producer Joe Henry gently placed honesty and honor, introspection and intention. The result won't rise above a barroom din, but it'll certainly sink into a listener's heart.

Between KMAG and Lovers, a lot has happened in your own life and the world around you. What's the one thing, though, that made the biggest difference in you and your music?

I don't know if there's one thing. I can just say that I changed. [Laughs] A lot happened in a lot of different parts of my life. My personal life had a lot to do with it. My marriage ended. That sort of forced me to take stock of where I was in my life and what was going on, and that influenced everything around me. I turned 40, which felt significant, in a way, in that I'd been living a certain kind of life for a really long time and kind of looked up one day and asked myself, “Is this how I want to live? Is this the kind of artist I want to be?” and just took stock of all that. That all influenced the record that I made.

Outside of that, in the world-at-large, I don't know that it influenced anything that I did, but it feels like people are appreciating an honest, sincere songwriter in a way that … that sounds really boring, but … [Laughs] “I don't know if I want to go to that show. He's honest and sincere. Yuck!” [Laughs]

But there's so much bullshit in the world right now that, when you find something that's a little bit True … capital “t” True …

Yeah. Yeah. Something with some authenticity to it. I do think that goes a long way. And maybe people are responding to it in a way that they haven't of late. I see a lot of writers and singers who are doing really well, and I think people are connecting with how they put their work out into the world.

Jason Isbell pops immediately to mind.

Yeah, absolutely.

Like him on Southeastern, you didn't give yourself a whole lot to hide behind on this one, sonically or lyrically.

That was a real conscious choice. I always had given myself something to hide behind. I always kind of couched my serious moments with humor or with musical pomposity. I never felt comfortable being that exposed. I think it had a lot to do with how I came up playing to crowds … you start out in these bars where, if you didn't get their attention, if you couldn't make them laugh or get them dancing, you didn't get the gig or you got something thrown at you.

So I always had this mix, as a performer and as a writer, that I was aware of both things. I aspired to be Townes [Van Zandt] or [Kris] Kristofferson and be able to capture people in a certain way, but I also felt a real need to make sure that people didn't lose interest. I think I was always a little insecure about whether my words and voice, alone, were enough to keep people there. So I always felt that — whether it was onstage and connecting to them through stories or jokes, or in the music being as super-varied as my limitations would allow.

I've seen you in a few different settings, and a song like “Beaumont” always goes over really well. So I think your fans have been with you on the poet side, as well as on the cowboy side.

Yeah, I've been lucky. I have a pretty broad fan base. I've tried to never pigeon-hole myself. Whether it was playing the Texas country scene or honky-tonks across the country or going over to Europe or playing the listening rooms and folk rooms or working with people outside of my respective genre, I never wanted to feel like, career-wise, that I was stuck somewhere. I always wanted to have options. The job is too cool to go out every night and feel bored or feel like you have to do the same thing every night. So I always wanted to be able to keep that door open.

With this record, I realized that, if I wanted to make a record like this, now was the time … because, if you don't do it and show that side of yourself at some point, then it gets harder and harder for people to accept it. It was where I was at in my life and where I was at creatively, and it just made sense to me. I thought, “Whether anybody likes this or not, it's the record I need to make and it will change where I'm at, and it's reflective of my search for connecting onstage every night and what I want my life to be like.” So, for this moment in time, that was what I needed to do. It feels weird. It feels naked.

The obvious way to look at songs is that they reflect their writer. But you can also turn that lens around, right? Do you sometimes feel like you want to reflect — or maybe even live up to — something you've written?

I think I've, at times, written to a certain audience. I've written mostly just for myself about where I was at, but I've also written individual songs or just a style that I wanted to keep open for myself. I think I've written, at times, for what I wanted my performances to be and what I wanted my career to be.

I love playing honky-tonks. I love having 1,000 people at a rock club going nuts. But I very much value my ability to go play solo in a listening room and have a completely different experience. That's kept me engaged, kept me alive. That's, honestly, how I feel most connected and comfortable as a performer, because I don't need to rely on a bottle of whiskey. I don't need to rely on volume. It's me, a guitar, and these songs. They either hold up or they don't, but I have a much more immediate understanding of whether it's working or not when I'm in a more stripped-down setting.

And to make a record that reflects that … yes, it's emotional and it's creative, but it's also a little bit practical because that's job security, if you know you can always go out and play your songs solo or you know that you can make a pretty simple recording. Those are the records that stand up and become classics for the generations.

A couple of years ago, I realized that, whatever happens — whether I become a big alt-country star or whatever — that I've got a collection of songs and I'll continue to write, and worst case — and it's not all that bad of a case scenario — I can go do house concerts and folk rooms and there will be some group of people that is drawn to that music. I think maybe even more than the financial side, I just wanted to keep that open for myself. And I needed to do it now or it might not ever happen.

I always talked about having a sonically cohesive record that was a songwriter record, that was sparse, and I'd never quite done it. I'd make attempts at it, but then I would cover it up with a joke or some bombastic rock and never just let that stand on its own. I'd always, I guess, been scared to put that out there. Maybe I didn't have faith that that was enough for me, and I needed to prove to myself that it was.

So that's why I'm excited about this record. There's no single on there. It's not going to get any radio play. It's not anything people are going to play at a party. There's nothing to dance to — all these things that I could kind of peg, like, “Okay, I've got that covered and that covered and that covered.” It's sparse and emotional and personal and intimate. But listening to that and not pulling people off in other ways can get you into a headspace, as a listener, that you can't get, necessarily, if you're jumping all over the place. I'm trying to have trust that this can work. So I did it. And, whether anybody likes it or not, I'm proud of the record. That probably doesn't sound like that big a deal to a lot of people, but for me, it was important to be able to take that step, creatively and artistically.

As you were writing, instead of checking off the things you wanted, were you checking in with yourself and checking off the things you didn't want? Like, “Oh, I just habitually took this song there and I need to pull it back.”

I don't know, as I was writing, how conscious I was of that because I wrote a lot of stuff that is completely incompatible with this record. I had a lot of those things that are funny or rocking or even were more subtle but just didn't feel like they were part of this story. There are very few songs I can think of where I sat down and said, “Okay, I'm going to write for this record.” I was just writing.

And they emerged as a group?

Yeah. Themes started showing themselves. I've never been able to sit down and write thematically. I've never had the attention span to stay consistent about it. There were definitely things I was writing about in my life, here, that came out. But there were also songs I'd written before a lot of this happened that sort of fit that narrative and that part of the story, though that was not my goal when I wrote them, initially. But I'd look at them and go, “I thought it was this one thing, but it actually fits really well with what I'm doing here.”

Setting aside music as your own artistic outlet, what role does it play in the Life of Hayes? Friend? Therapist? Pastor?

It's been all of those things — and none of them — at times. It sort of depends when you catch me. Certainly, growing up, it was my teacher, my inspiration. It was my joy. It was this very mystical, foreign thing. I grew up in the suburbs and these people I was listening to, particularly the songwriters — [Bob] Dylan, Kristofferson — they took me to another place, far from where I was, and that was something that I really needed. I struggled to find my identity and an ability to articulate some of the things that I had on my mind. A lot of these guys did all that for me. They gave me some kind of identity. I felt a connection with them. I felt, “These are my people.” And it moved me. I got into Townes. There's music that can affect your life in such a deep and powerful way that everything else seems trivial.

Something I've struggled with a little bit over the years is that I have that connection to writers like that and, then, I have a connection to Chuck Berry and Jimmy Buffett. There are a lot of different elements and that hodgepodge has kind of made up my style, for most of my career. But, yeah, it can turn my day around, for sure, and keep me going.

When I interviewed Lee Ann Womack last year, she commented that sometimes she feels guilty connecting herself to you through recording “Chances Are,” and she thinks, “I hope Hayes doesn't mind that I cut his song.” Various award nominations later, may we assume that you, in fact, do not mind too much?

[Smiles] Yeah, we're talking again now. [Laughs] I was honored that she recorded it.

It's done pretty well for the two of you.

Yeah. To have the life that it's had with the Grammy nominations was completely unexpected for me. It was very cool. It took a lot for it to set in when I got the news. I thought, “Okay. Yeah. Fine.” I had sort of trained myself to not care about these things. I didn't even know when the Grammys were being announced. I had no idea it was a possibility. I have tried to distance myself from needing those things. So, when it happened, I was like, “Oh, yeah. It's no big deal.” Then, as I started getting congratulations from family and friends, and seeing the reaction that this news had on them, I started feeling like, “Oh, this is significant.” And not that it validated me for myself, but it was important to a lot of people who are important to me.

So, anyway, I'm honored that Lee Ann cut it and couldn't have been happier with its life.

So maybe you'll let her have another one at some point?

Yeah. Yeah. Absolutely. I just did a tour with Aubrie [Sellers, Womack's daughter]. Hopefully, Lee Ann and I can play together some day.

I met Lee Ann up in Colorado in Steamboat Springs. There's a little country festival up there. I remember I was sitting in this room, like a suite, and a bunch of my friends were up there playing and picking. I played “Beaumont,” and there was this little person with a hat pulled over, in a chair, legs up in the chair … I had no idea who it was. And she goes, “That's a really cool song.” Or something to that effect. I went, “Thanks … whoever you are …”

[Laughs] “… little hidden troll in a hat.”

[Laughs] Yeah. I didn't put it that way! Then it was, “Hayes, meet Lee Ann.” And we got to do a thing here in Nashville with Sirius XM and [Bobby] Bare, Jr. and Bobby Braddock and Lee Ann, which was super-cool. He played “He Stopped Loving Her Today” and Lee Ann sang “Chances Are.” It was the first time I got to hear it, sitting right next to her.

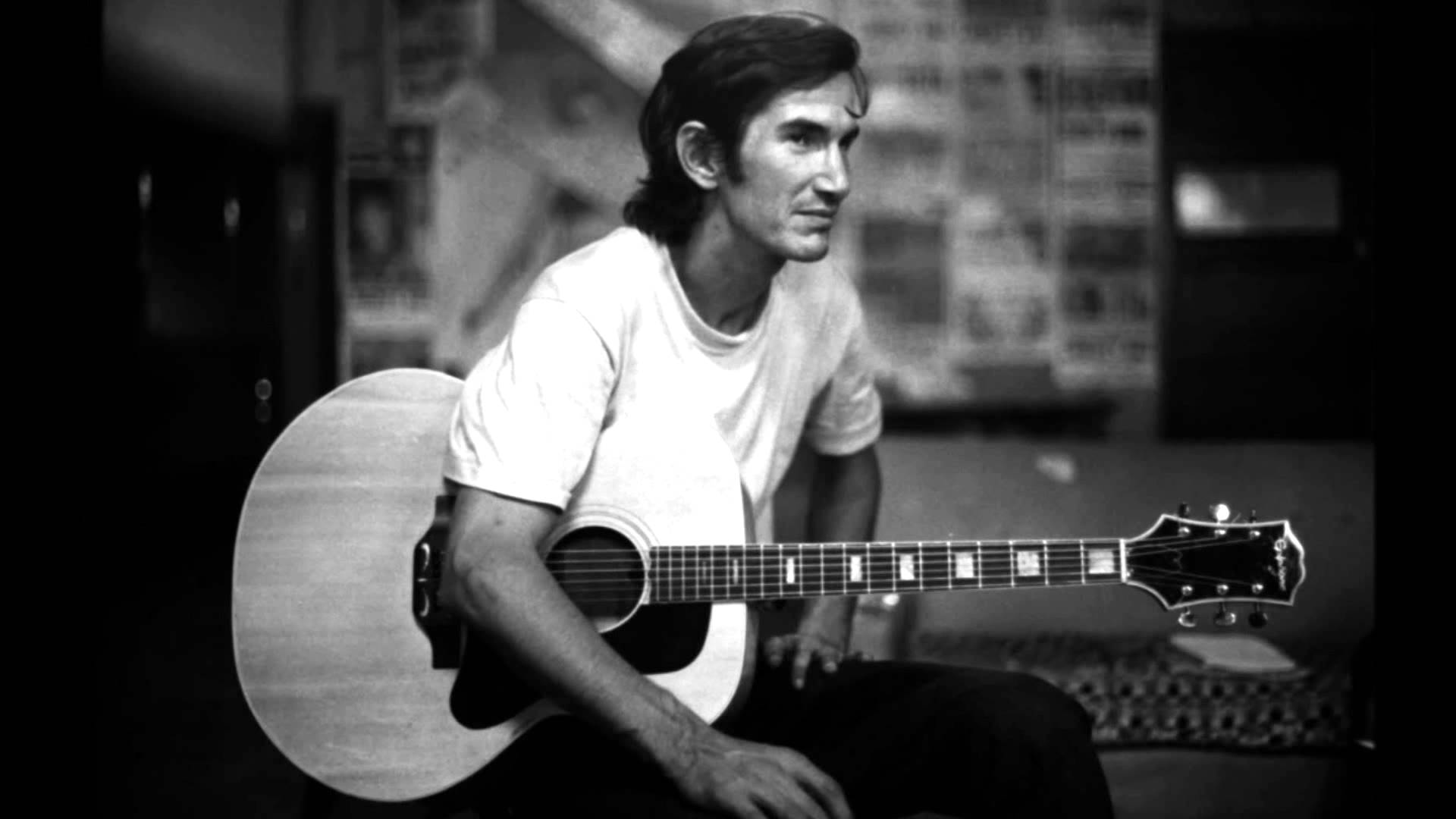

Photo credit: Jacob Blickenstaff

In the 1940s, this was one of the first nightclubs to feature folk music. The great protest and folk singer Josh White held court at Café Society for five years. Billie Holiday and Lester Young were regular performers in what was one of the first clubs to truly break color barriers. When Dylan lived here in 1962, it was the Haven — one of New York’s largest openly gay nightclubs.

In the 1940s, this was one of the first nightclubs to feature folk music. The great protest and folk singer Josh White held court at Café Society for five years. Billie Holiday and Lester Young were regular performers in what was one of the first clubs to truly break color barriers. When Dylan lived here in 1962, it was the Haven — one of New York’s largest openly gay nightclubs. Keep heading toward Dylan’s apartment and then turn right on Jones Street.

Keep heading toward Dylan’s apartment and then turn right on Jones Street. This is the street from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album cover. Take some photos and continue down the street — at the end is Caffe Vivaldi. Pop in for a beer. It’s a great place to hear some burgeoning New York musicians, as it is still home to songwriters and one of the only clubs with a piano. It’s a great old room.

This is the street from The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan album cover. Take some photos and continue down the street — at the end is Caffe Vivaldi. Pop in for a beer. It’s a great place to hear some burgeoning New York musicians, as it is still home to songwriters and one of the only clubs with a piano. It’s a great old room. This room has a rich history. It was first the Commons. Opened in 1958, the Commons was originally a small theater and café that was tres bohemian. It was also one of the first basket houses — a coffee shop that had live music — in Greenwich Village. The performers were paid in tips, which were collected in a passed basket. The Commons expanded in 1960 and changed its name to the Fat Black Pussycat. This is where Dylan wrote "Blowin' in the Wind."

This room has a rich history. It was first the Commons. Opened in 1958, the Commons was originally a small theater and café that was tres bohemian. It was also one of the first basket houses — a coffee shop that had live music — in Greenwich Village. The performers were paid in tips, which were collected in a passed basket. The Commons expanded in 1960 and changed its name to the Fat Black Pussycat. This is where Dylan wrote "Blowin' in the Wind." Dylan performed at Café Wha? on his first day in New York. It was an open mic hosted by Fred Neil. Fred Neil is best remembered as the songwriter behind “Everybody’s Talking” from the film Midnight Cowboy. In 1961, he managed the café’s day bookings and MC’d the open mic. Dylan did a set of Woody Guthrie songs and Neil hired him on the spot as his harmonica player.

Dylan performed at Café Wha? on his first day in New York. It was an open mic hosted by Fred Neil. Fred Neil is best remembered as the songwriter behind “Everybody’s Talking” from the film Midnight Cowboy. In 1961, he managed the café’s day bookings and MC’d the open mic. Dylan did a set of Woody Guthrie songs and Neil hired him on the spot as his harmonica player. This café is virtually unchanged from the day it opened. Without a doubt, Dylan spent time here. You might also recognize it from the film Inside Llewyn Davis. Caffe Reggio also claims to be the birthplace of the cappuccino.

This café is virtually unchanged from the day it opened. Without a doubt, Dylan spent time here. You might also recognize it from the film Inside Llewyn Davis. Caffe Reggio also claims to be the birthplace of the cappuccino. The Gaslight was the place to play in the 1960s. It was the Carnegie Hall of folk music, where Dave Van Ronk hosted the weekly hootenanny every Monday and Dylan was one of the regular performers within a year of moving to town. There were typically five performers each night and they would rotate every four songs. It is a tiny spot, and there would be lines stretched down the block. Before being converted to the Gaslight, this was the coal room for the building. The walls were stained black from years of storage, but the room embraced it and left it dark. It’s also been rumored that this is where the beatniks began snapping instead of clapping, so as not to disturb the upstair tenants.

The Gaslight was the place to play in the 1960s. It was the Carnegie Hall of folk music, where Dave Van Ronk hosted the weekly hootenanny every Monday and Dylan was one of the regular performers within a year of moving to town. There were typically five performers each night and they would rotate every four songs. It is a tiny spot, and there would be lines stretched down the block. Before being converted to the Gaslight, this was the coal room for the building. The walls were stained black from years of storage, but the room embraced it and left it dark. It’s also been rumored that this is where the beatniks began snapping instead of clapping, so as not to disturb the upstair tenants. This is the former Kettle of Fish. When not performing, the musicians would eat and play cards up here.

This is the former Kettle of Fish. When not performing, the musicians would eat and play cards up here. Izzy Young from the Beatnik Riots was the proprietor. Dylan referred to the Folklore Center as “The Citadel of American Folk Music.” Izzy was a notoriously bad businessman, but his folklore center was the hub of the New York folk revival. Van Ronk, and countless other musicians, were technically homeless — although they always had a place to crash. This was where their mail was sent. It was also where Dylan came to absorb records and learn new songs.

Izzy Young from the Beatnik Riots was the proprietor. Dylan referred to the Folklore Center as “The Citadel of American Folk Music.” Izzy was a notoriously bad businessman, but his folklore center was the hub of the New York folk revival. Van Ronk, and countless other musicians, were technically homeless — although they always had a place to crash. This was where their mail was sent. It was also where Dylan came to absorb records and learn new songs. Continue to 152 Bleecker Street where the old Café Au Go Go is now a Capital One Bank. Café Au Go Go was a cultural hotbed in the 1960s hosting folk, jazz, comedy, blues, and rock. The Grateful Dead played their first New York show at Café Au Go Go. A young Joni Mitchell had a weekly gig. Blues legends Lightnin' Hopkins, Son House, Skip James, Bukka White, and Big Joe Williams performed at the club after being "rediscovered" in the '60s. Young Bob Dylan spent many nights listening to his peers and forefathers.

Continue to 152 Bleecker Street where the old Café Au Go Go is now a Capital One Bank. Café Au Go Go was a cultural hotbed in the 1960s hosting folk, jazz, comedy, blues, and rock. The Grateful Dead played their first New York show at Café Au Go Go. A young Joni Mitchell had a weekly gig. Blues legends Lightnin' Hopkins, Son House, Skip James, Bukka White, and Big Joe Williams performed at the club after being "rediscovered" in the '60s. Young Bob Dylan spent many nights listening to his peers and forefathers. This is where Dylan came up with the Rolling Thunder Review. When he moved back to Greenwich Village in the '70s, he spent many nights at the Bitter End. There were many late-night jam sessions and, one night, he decided to take this loose collective on the road. He recruited some of his famous friends, hired a film crew, and embarked on one of the most ambitious tours of the 1970s. The Bootleg Series put out an amazing double album, and Heavy Rain was recorded on this tour. If you’ve ever seen Dylan in white face with a pimp hat, it was from the Rolling Thunder Review.

This is where Dylan came up with the Rolling Thunder Review. When he moved back to Greenwich Village in the '70s, he spent many nights at the Bitter End. There were many late-night jam sessions and, one night, he decided to take this loose collective on the road. He recruited some of his famous friends, hired a film crew, and embarked on one of the most ambitious tours of the 1970s. The Bootleg Series put out an amazing double album, and Heavy Rain was recorded on this tour. If you’ve ever seen Dylan in white face with a pimp hat, it was from the Rolling Thunder Review.