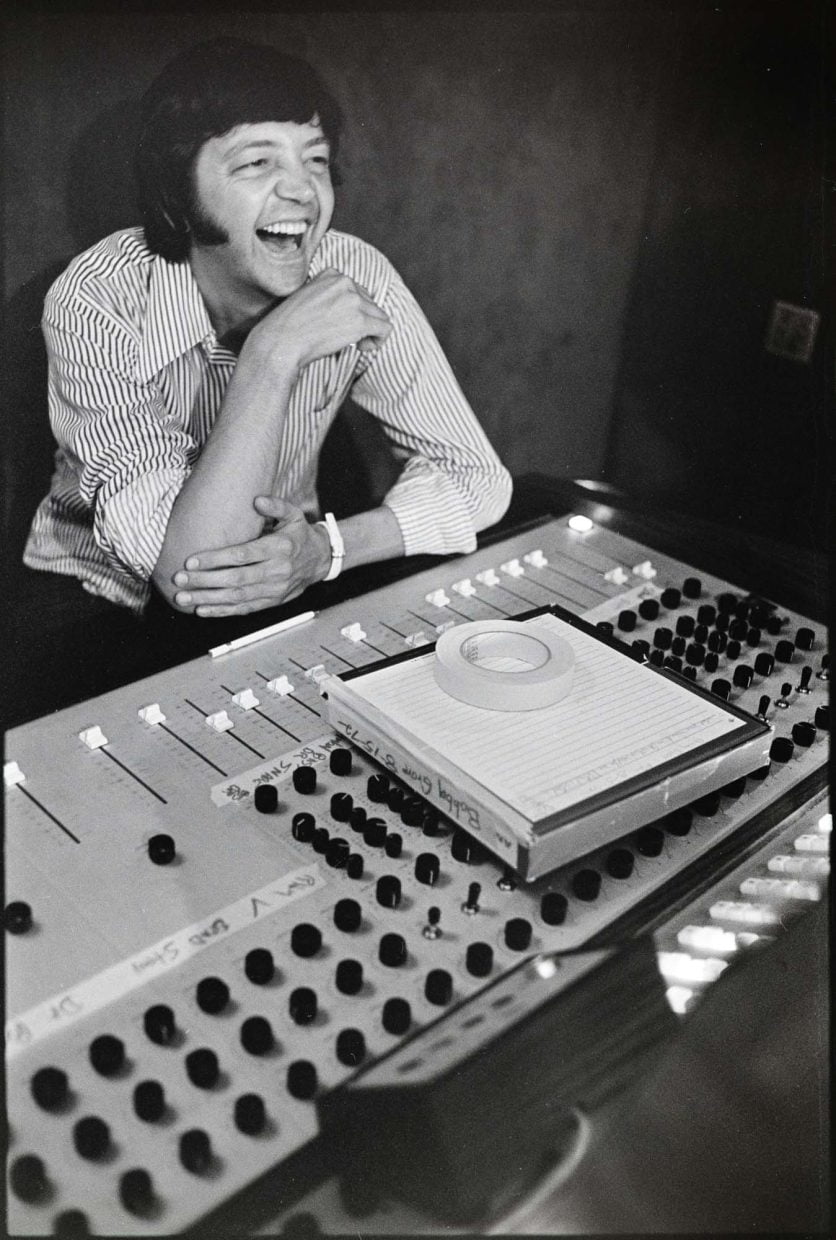

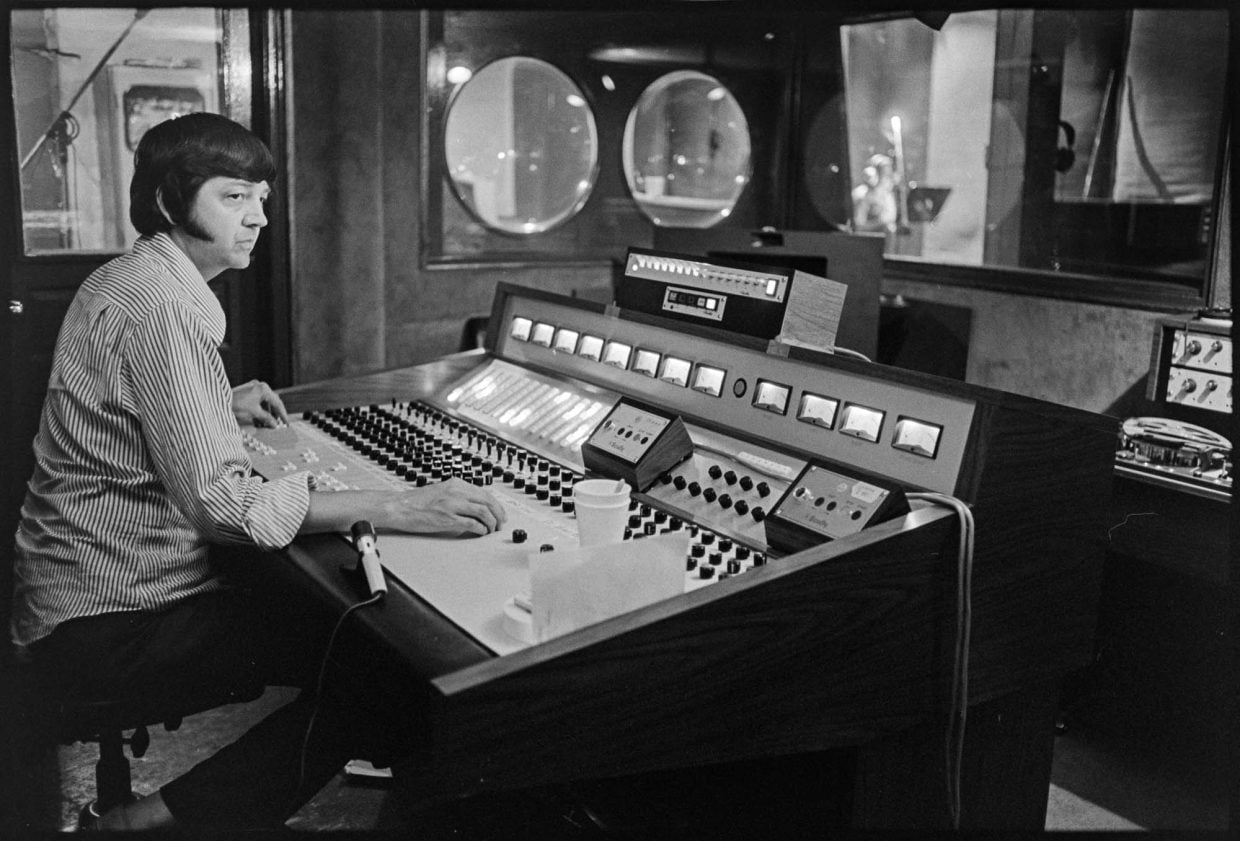

(Editor’s note: All inset photos by Carl Fleischhauer.)

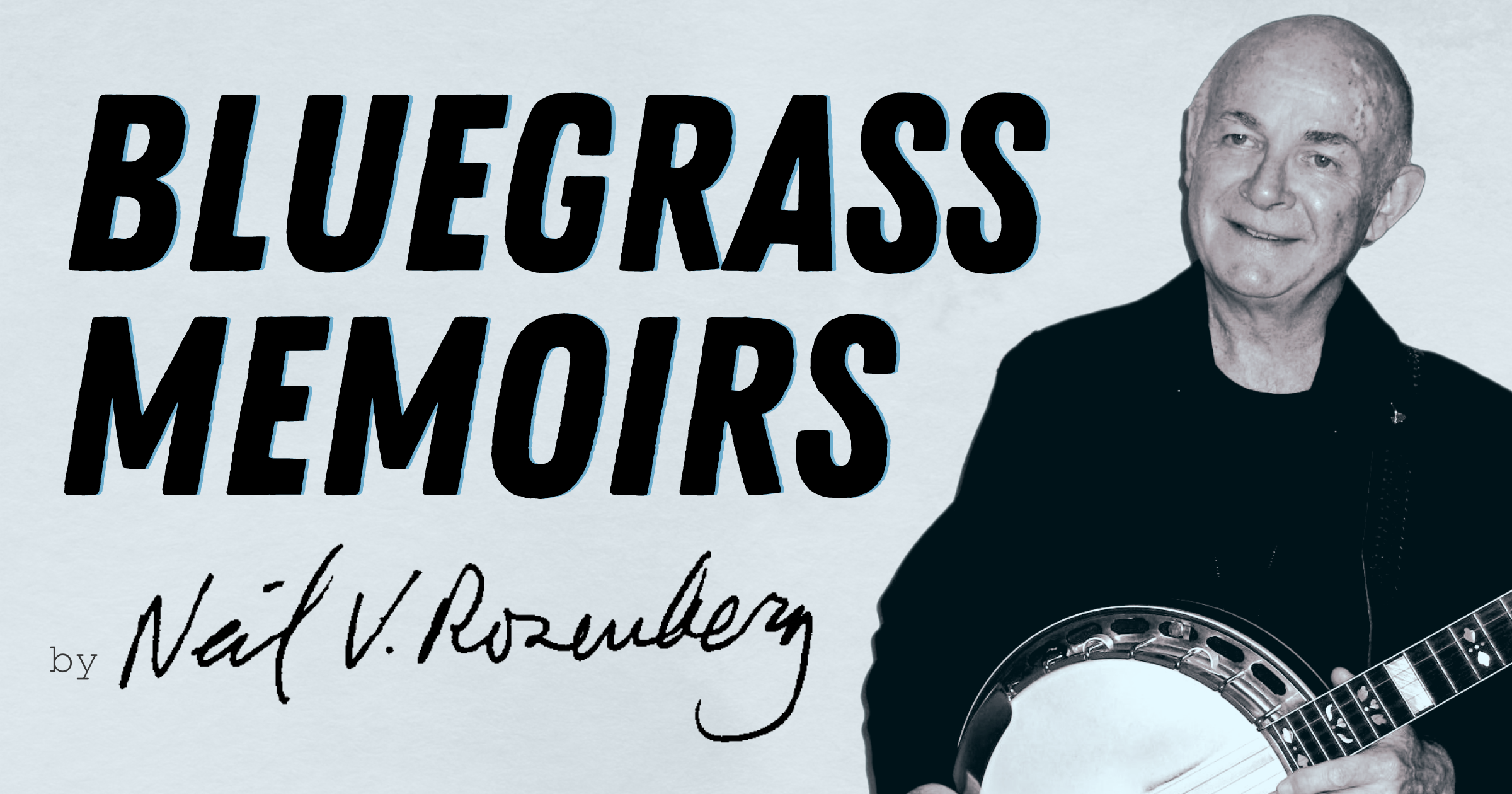

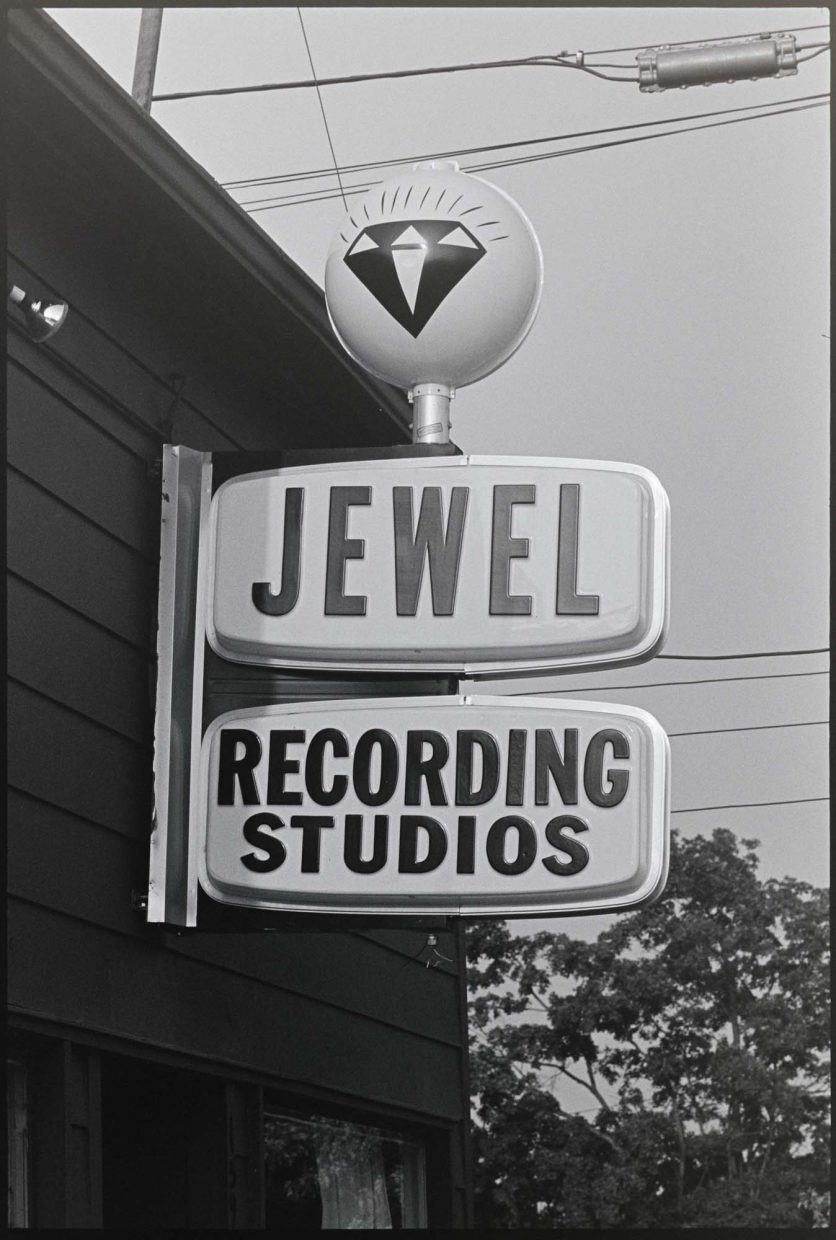

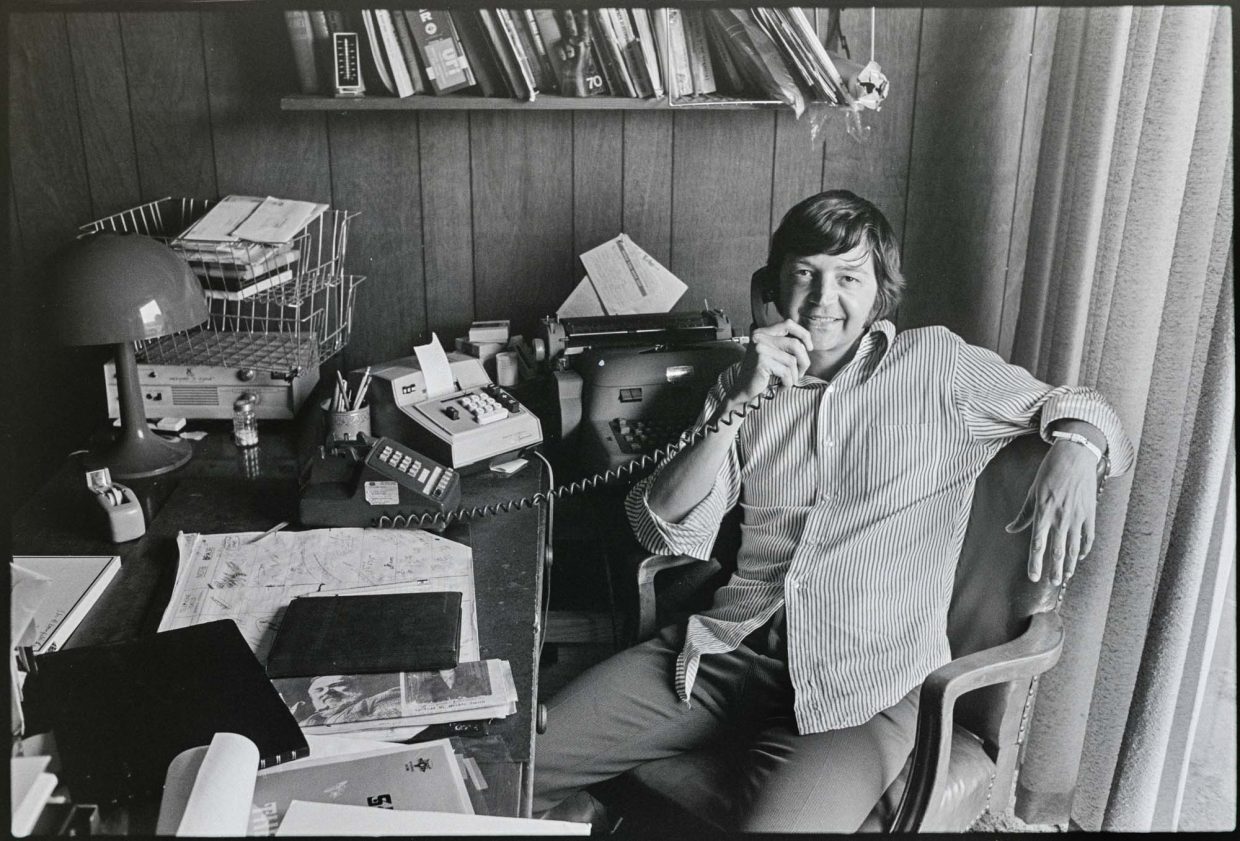

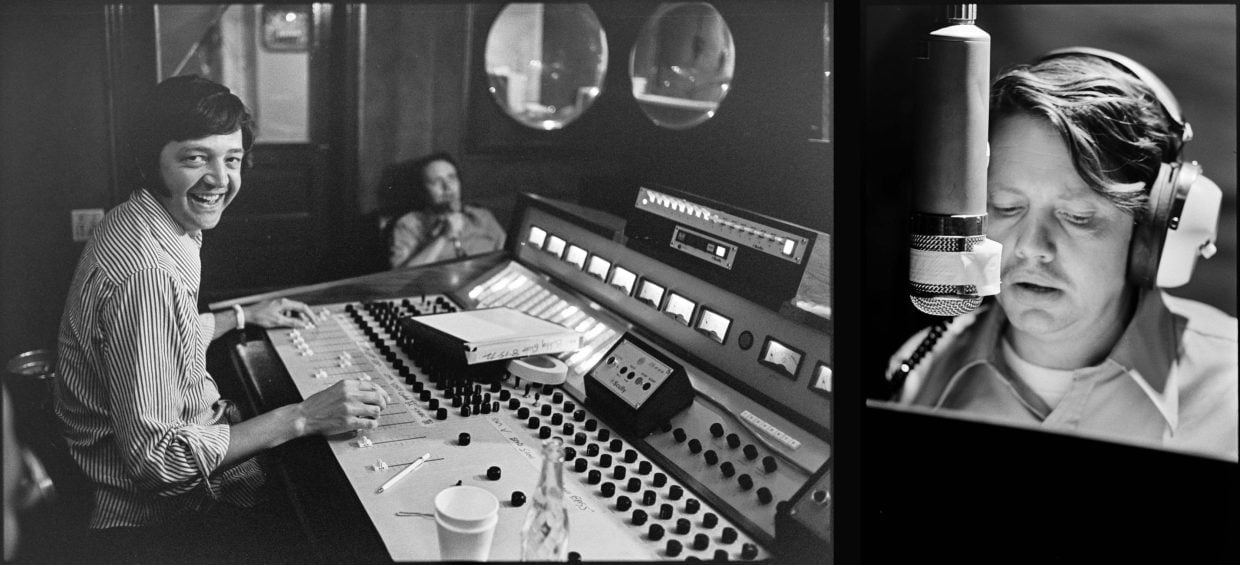

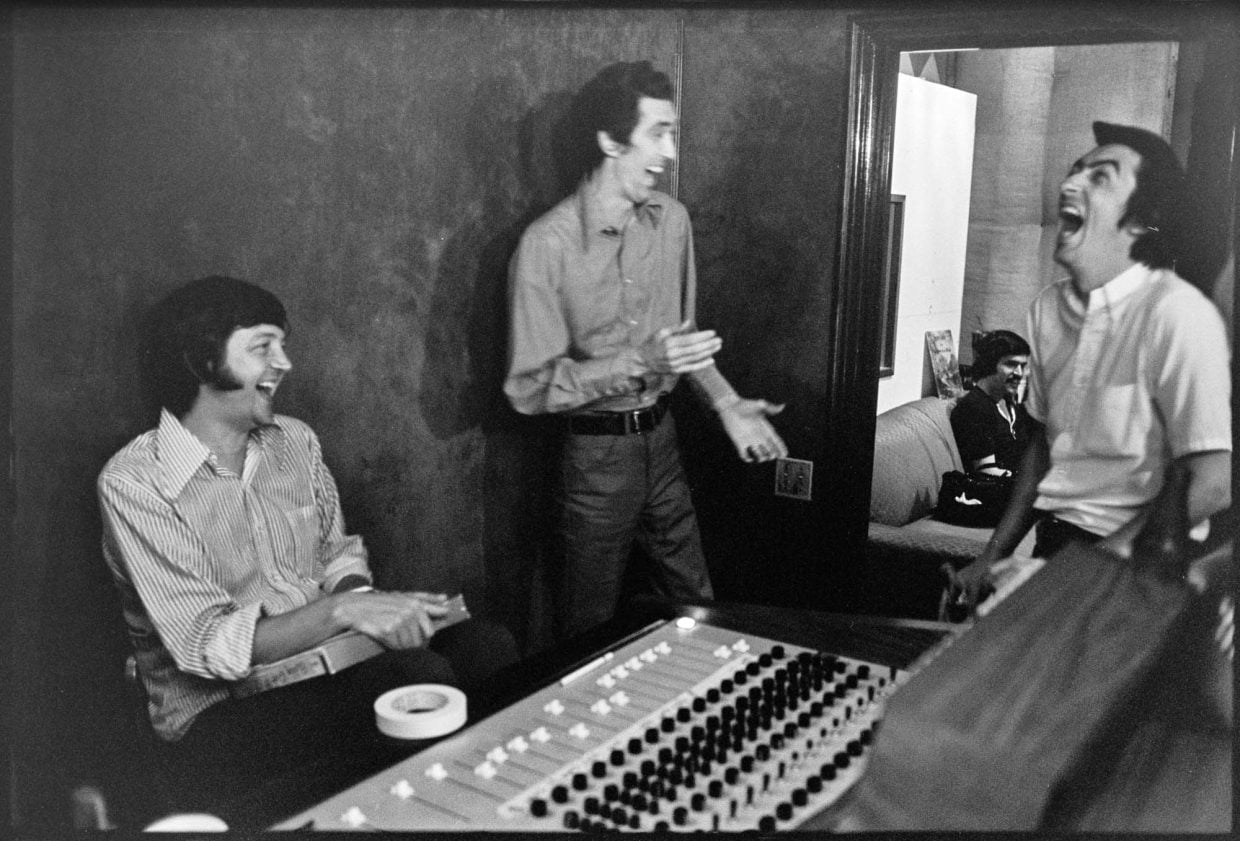

In my previous memoir I described what I knew of Rusty York when Carl Fleischhauer and I arrived at his Jewel Recording Studios in Mt. Healthy, Ohio, on the afternoon of August 15, 1972.

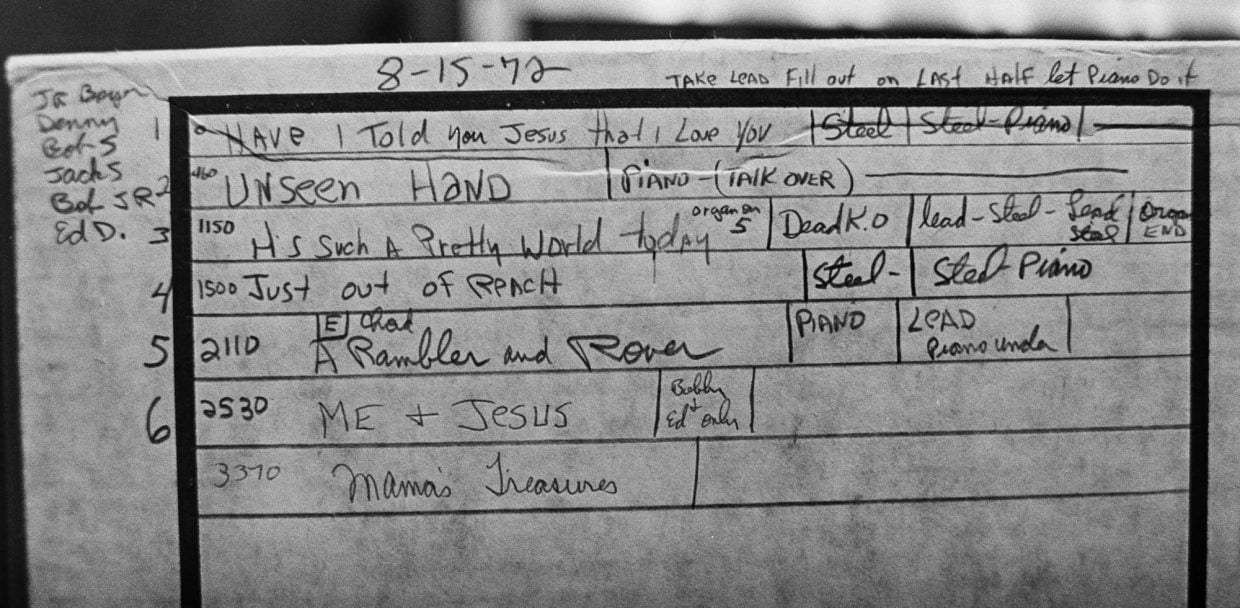

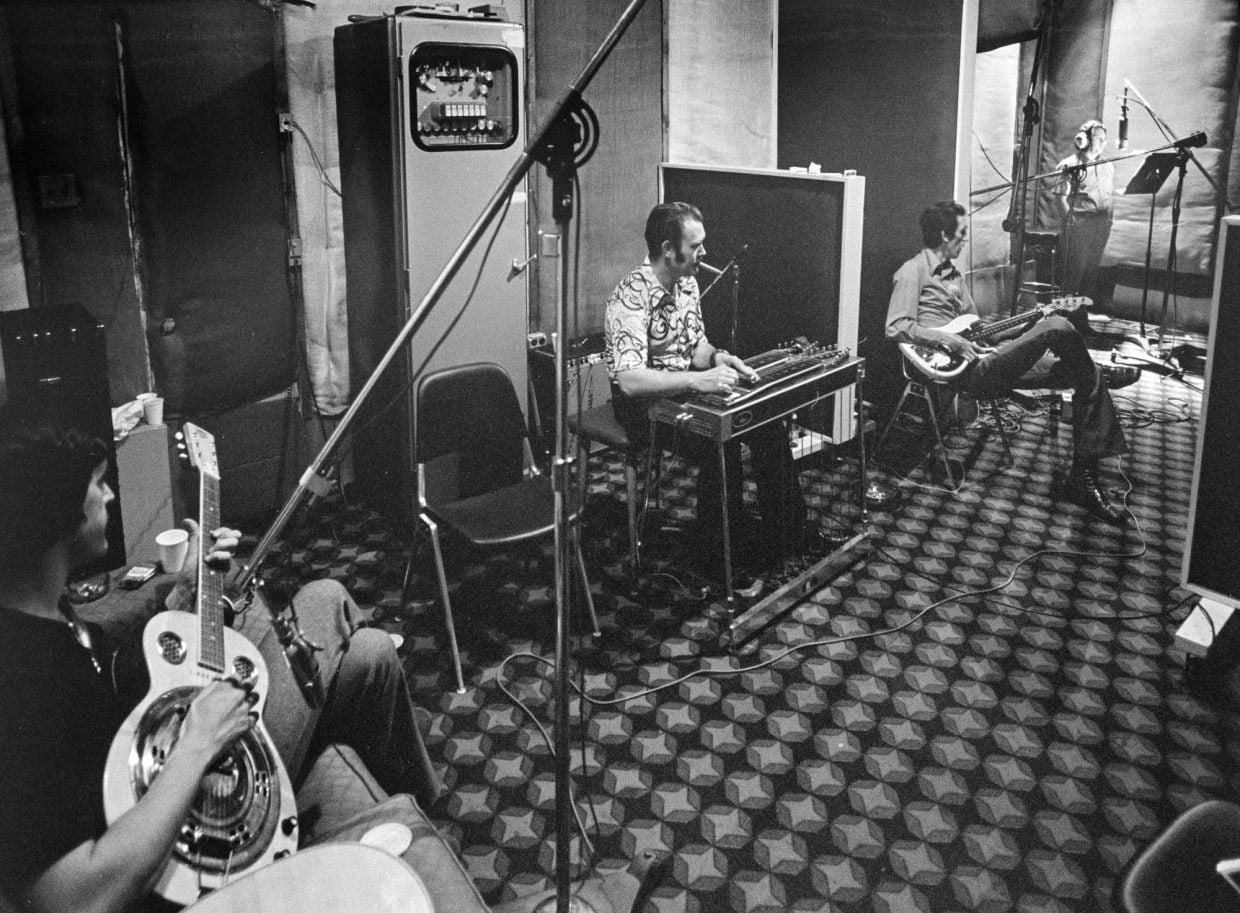

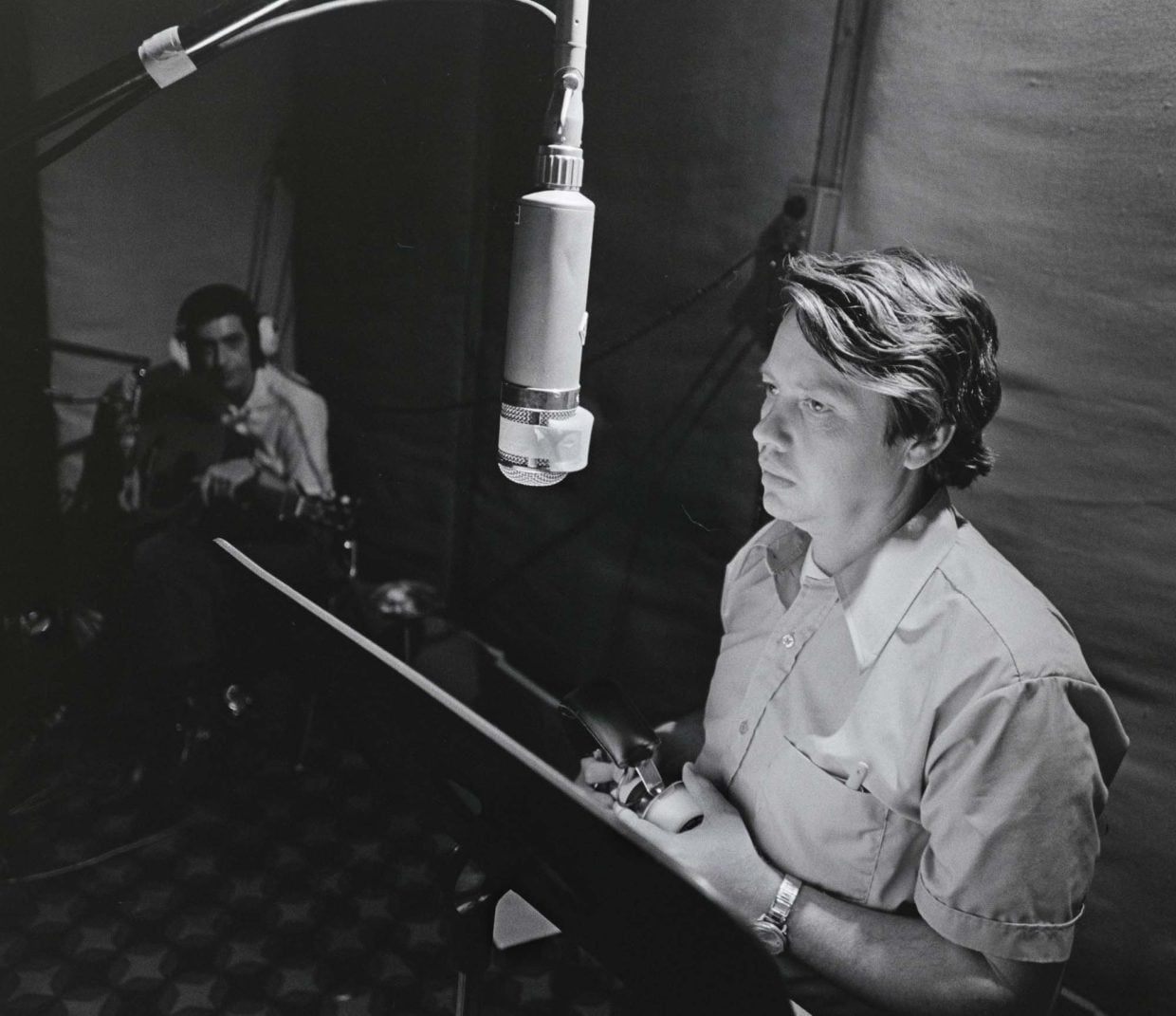

We had walked into the midst of a recording session. In the studio was the Reverend Bobby Grove (née Musgrove), his wife Fayette, oldest son Bobby Junior (a drummer), some other friends, and five studio musicians – Eddie Drake, lead guitar; Junior Boyer, pedal steel; Bob Sanderson, bass; Jack Sanderson, rhythm guitar; and Denzil “Denny” Rice, piano.

Later I wrote in my notes:

Grove has made 35 LPs. Has a “club” – he mails out each record to a list of 10,000, with a request for a minimum contribution of $4.00.

Originally from Kentucky, the Groves now lived in Hamilton, Ohio, where Bobby had opened his own church about four years earlier. I noted:

Rusty makes up soundtracks for him from the LP masters which are minus the voice tracks – he uses these in personal appearances.

Bobby’s wife Fayette described this process to me. “Really cuts down on the expenses. He just takes the soundtrack along. It’s really marvelous,” she said.

The studio was probably about a fifty-foot square, with the master panel occupying a quarter, the studio space an “L” around it… In the recording room, where I set up my cassette (it looked ludicrous!), was an 8 track, a 16 track and a 2 track. The recording was being done on 8 tracks.

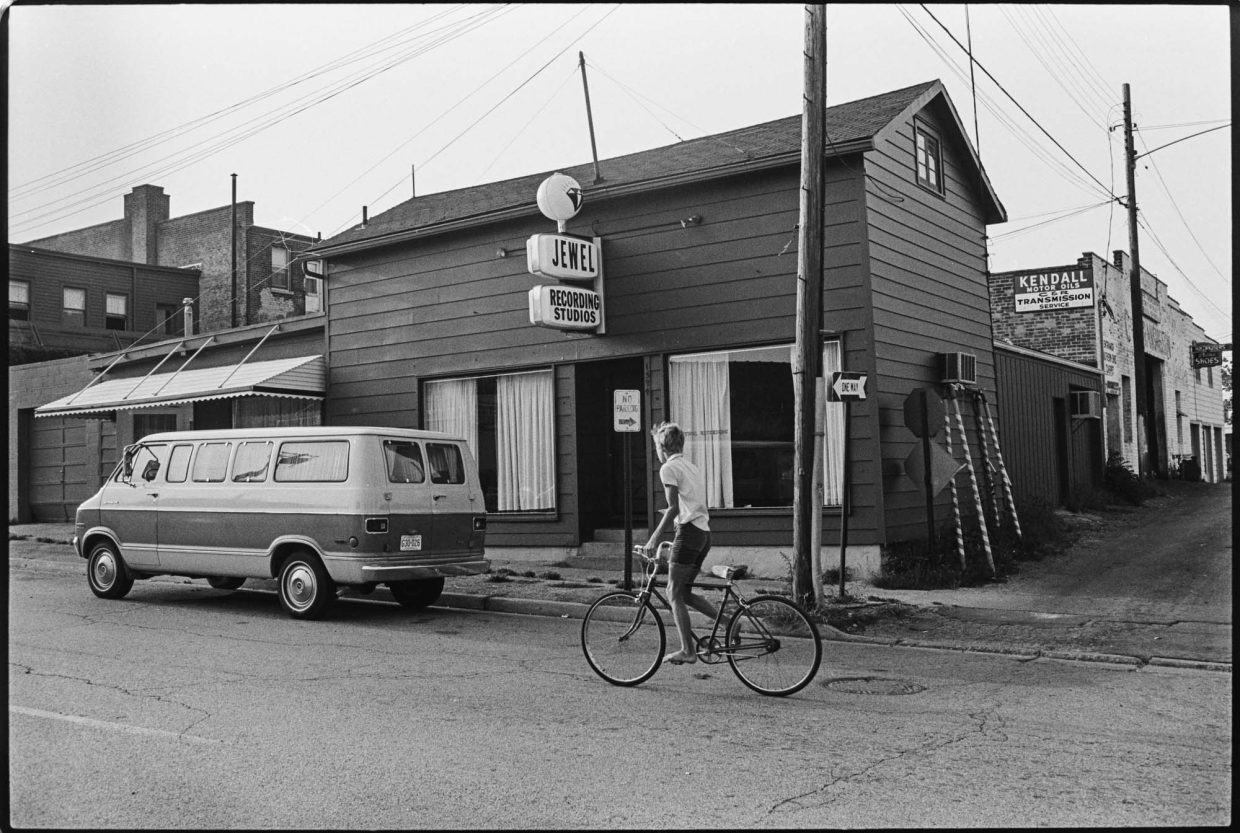

I ran the cassette intermittently trying to get snatches of conversation and brief interviews between phone calls, takes and visitors which never seemed to ruffle Rusty’s feathers. Obviously, he is a person of tremendous energy and talent, starting with his musical abilities (from rock to ‘grass) going to his present recording activities.

During this session Bobby had his bible tucked under his arm during every “take.”

After recording several songs, he asked Rusty: “Would it be all right, these next three songs, if I just sang the words — the country words — and then come in and do ‘em, like that? Then I’ll write ‘em. That way I’ll do something that we know real quick and we’ll just go through it and I’ll go home and write ‘em. And when I come in and mix it down just dub it in real quick?”

Rusty said, “Yeah that’s fine.”

In the five years since I had seen him, York had expanded…to two studios (the other, bigger, in Hamilton) with loads of sophisticated equipment.

Rusty: “I bought a professional recorder in ’61, just in my garage. In fact, you know, you were out there.”

“So, you got into it kind of gradually,” I respond.

He nodded: “I didn’t just go and buy a hundred thousand dollars’ worth of equipment like a guy I knew here in town. He’s hurting; but I’m booked, you know, all the time.”

“Since you do this all the time,” I said, “you probably get rates from the pressing people, and so on?”

“I’m their biggest customer, yeah.”

What drew him into recording, I wondered.

He explained: “It just happened. It was really nice to make fifty extra dollars on Sunday, you know, by doing our own album, you know. Or some kind of session. Still, I still play music, I thought that’s what I want to do, you know. It got to be a, where I could make so much more money and not be the big hassle, like getting stoned every night that you played, chicks all over your body.” [Laughter]

Rusty appeared to be paying only scant attention to the recording session but every once in a while, would pinpoint out-of-tune instruments (…he can isolate mikes from the fairly well-baffled studio and hear exactly who’s doing what), suggest drum riffs, etc.

Rusty explained to us that his connections with Bobby Grove reached back to his earliest days in Kentucky:

“Yeah, we’ve all worked together at one time or another. Willard and I worked at Bobby’s father’s, he had a little barn dance and that, the Stanley Brothers –”

Grove’s son interjected: “Grandpa!”

Rusty said, “Huh?”

“You met my grandpa.”

“Yeah, probably before you was born.”

I asked: “What was his name?” “Jason Musgrove,” Rusty said.

Grove’s son recalled the venue well: “Did you know in that barn he had a sign, said no alcoholic beverages allowed in this area? He stayed drunk there all the time.”

“No!” Rusty replied in a mock serious whisper.

“That’s right”

“Well, we had a bottle or two out in the front of our car all the time.”

Grove: “I can picture him wrestling a bear.”

Rusty: “We saw a bear-wrestling match in there.”

Grove: “Was you there when that happened?”

Rusty: “Yeah. Were you around?”

Grove: “No, that was when I was born. ‘56” [Laughter]

Rusty explained: “His grandpa ran a, what did he call it? Green Valley Barn Dance. And right now, that place is worth millions of dollars, and he lost it cause he couldn’t make the payments or something. Forty-two dollars a month payment.”

Grove: “Kent Valley Lake”

“Now it’s, you know, you could probably get twenty, thirty million dollars for the place. Got a big lake –”

“I started playing, I guess, when I first come to Cincinnati, about ’52. I just picked up an old guitar. My father bought me an old five-dollar guitar.”

“I went to see Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs first time up in Jackson theater in about ’53, I guess. And I just couldn’t believe man, anybody could play a banjo like that, I just… Boy! I stayed for both shows that night… I mean it was just like heaven then, ‘cause nobody, you couldn’t never see it. There’s so much of it now, you know. Everybody can play good now, you know. But then, it was only him. I had a tenor banjo, I put fifth key on it. It was a Mastertone too, Gibson. Four-string.”

The only five-string banjo style he’d known before Scruggs was that of his Grandma. He recalled that she’d made the head of her banjo from a groundhog skin.

“Willard Hale was from Somerset. Where I met Willard, I stopped into a little bar out in Cincinnati, and they had music. They set up a little amplifier and the mandolin with the guitar. Willard and this other fellow were singing duets and one guy played the mandolin. I set in with my banjo and then this one guy left and I – every weekend, I’d go out and play with them. Like Friday, Saturday night. Boy, free beer! I couldn’t believe it, you know, getting free beer and a, I found out later that this guy was getting paid for me all the time I wasn’t getting any bread.”

“Willard and I used to just stand on the stage, two of us, and play banjo and guitar and sing duets. Then Elvis came along and they started saying, ‘Hey you know “Hound Dog”’ and you know, man, ‘You from the country, you shouldn’t be asking for a song like that.’ And even country boys started liking Elvis, you know. And we had to switch over to electric guitar and a guitar and then switch over to bass, and we finally had to add drums, then turned into modern country. Although we were the highest paid ones in Cincinnati for a long time, just Willard and I. …Our salary was on ten-fifteen bucks apiece a night, but the kitty would be the kind of money, might be fifty bucks a night. And that was a lot then.”

“The highlight of our whole night was when we got the banjo and upright bass and Martin guitar out. And boy people really dug it, but we didn’t give ‘em too much of it, cause they still like to dance. [Otherwise] I played electric guitar and the other boy played bass. And we might play, sometimes an hour of bluegrass. Really it was a treat, you know, a change for the people.”

“I played banjo – ‘Down The Road’ and things like that. And every, the whole place would swarm the floor, you know. They’d do this soft-shoe backstep buck and wing hoedown. That’s what I call it. It’s almost like square dancing without any organization. Everybody just doing their own thing. But it, it’s that clog, what I call – the soft-shoe backstep buck and wing hoedown.”

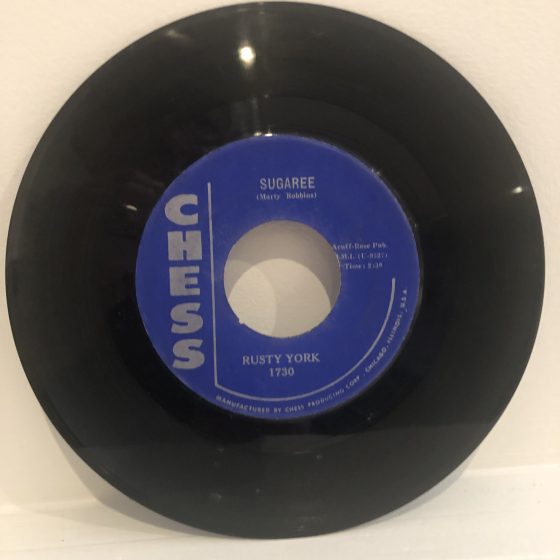

I was curious about “Sugaree,” that jukebox single I’d bought in Oberlin back in 1960. Rusty explained:

“I was doing, you know, some bluegrass stuff and this guy came to me, said — that’s when the Chipmunks were popular [1959] — he said let’s go and record this ‘She’ll Be Coming Round The Mountain’ we’ll go ‘She’ll be dum da da, Do diol lu’ (etc. — imitates twangy guitar doing first line of that song) and the Chipmunks go ‘Cha Cha Cha’ (high pitch).”

“On the way out there [to the studio] he says, what are we gonna do on the other side? I says, I don’t know. He said, well do ‘Sugaree’ or ‘Long Tall Sally’ or something, I said I don’t even know that. That was just decided on the way out to the studios. It was a bad record – shoo! I, I can’t stand to hear it.”

“We recorded it at King records studio. Paid for the session ourself. Forty bucks it cost. We tried to peddle it to everybody – RCA and Mercury – and nobody wanted it. So, we put it out ourselves on my [own label], started Jewel. It got to be number two in Cincinnati, and they said something must be happening, you know we pressed the thousand, sold them, pressed a few more and this guy, Pat Nelson negotiated with Chess Records and we leased it to them.”

“I did another record and they never released it. I died, as far as — I did the Hollywood Bowl, and American Bandstand with Dick Clark.”

I was also curious about those “Bluegrass Special” EPs he’d done in the early ’60s. Did he still have copies?

“Ah, I’ve got ‘em on tape, but I don’t have the actual records. You know, those sold a lot of records. Like 200,000… Used to hear Jimmie Skinner and I on that fifteen-minute thing [Wayne Raney show on WCKY], selling the package.”

Rusty told me about the next chapter in his story, which was new to me at the time:

“I went with Bobby Bare; you know I was front man for his show. Played Reno, Las Vegas and just about every state in the Union and I went to Europe, about ten countries. … in ’64 and ‘5. It don’t seem that long ago.” …

I replied, “It doesn’t to me either.” I asked, “You’re not playing any, now, then, are you?”

“No, I started back playing about two months ago in one of the biggest nightclubs here. I just couldn’t take it, ‘cause I’d have to get early do a session and I make 90 buck an hour here, over there I might make – I was playing for the door. Sometimes we would make six hundred bucks a night for the band and sometimes a hundred, split five ways. So–”

“I enjoy just sitting around and playing, but I don’t know, as far as getting before a crowd and doing a thing, I’m not crazy about it. It’s really work, to me. … Most people, I’ve found, have an ego problem. I don’t know if it’s ego or insecurity, but they want to get up before a crowd and sing and–”

“Work it out, up there?” I interjected.

“Yeah. Most, most people that are in the business are very insecure and [play to/depend on] the crowd a lot. Bobby Bare was … he was a nice guy but he was kind of a, well was insecure. He’d like to sleep maybe eighteen hours a day, escape from reality.”

I was struck by York’s insightful comment about musicians having an ego problem. In later years I’ve characterized it in this way: the musician, selling himself or herself, is both product and salesperson. It’s a vision that has stuck with me, like “Don’t Do It.”

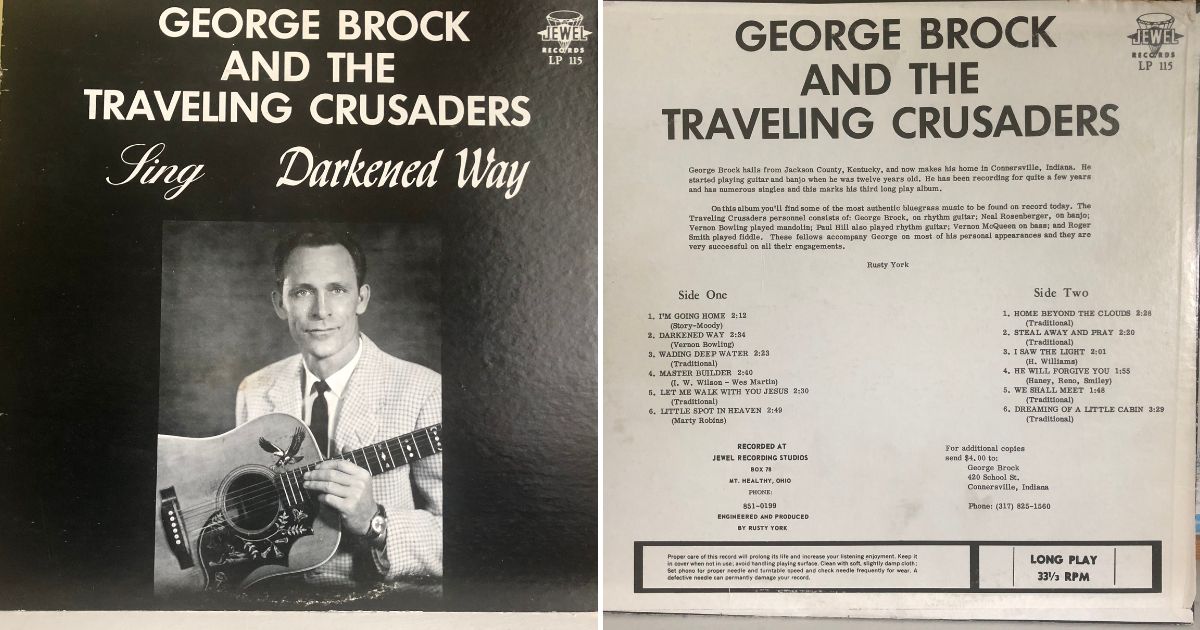

Since my research was focused on bluegrass, I was eager to hear what Rusty had to say about it. He began by talking about recording bluegrass.

“Here I don’t do a lot of bluegrass now. Most of them don’t have the money to afford to record. … I try to give ‘em a real good break. Something that’s gonna be around for a long time, I mean a bluegrass record is gonna be around forever, because there always will be somebody that likes bluegrass. I charge them a flat rate you know – sixteen hundred bucks or so for a thousand albums. In other words, they could not afford to pay studio time and do an album and pay for the tape and the mix so I just give them a flat break, price.”

I suggested, “You must know most of the good bluegrass musicians in this area.”

“Yeah, I do. They all want to record with me because they, I understand it a little bit better than some engineers.”

He told me that it’s the most difficult stuff to record, explaining:

“Well, most of ‘em play and sing at the same time. You got a mic for the banjo over here and voice up here — you got two mics, you’re gonna have phase cancellation between them. A mandolin player, you’re gonna have to do the same thing. The bass leaks into the voice mics, cause he’s got to sing too, and it’s really difficult. … And they want to get, this space is big and they all like to get right together.” Pointing to the spread-out, country sidemen working with Grove in the studio, he said: “See how far apart these guys are now? And they won’t overdub. It’s a real challenge, I’ll say that. To get a real group in here, that’s really got good harmonies, you know that’s really nice. I’d almost do it for nothing.”

I asked, “Do the country DJs around here play much bluegrass?” “The Osborne Brothers,” he said, adding “Paul Mullins plays a lot of bluegrass. He’s very well liked and a lot of people listen to him. He’s got little witty – you’ve heard him – little witty sayings and he’s about that… Yeah, I’ve got an album by him coming out by him. It should be out any day now, that he cut here.”

I closed my notes for that day summarizing the work at Jewel:

Rusty’s operation involves packages – he sells 1,000 finished LPs for $1600 (more or less, depending on studio time, number of tracks – the latter a function of tape since 16 tracks takes 2” tape, etc.) and he sees to recording, mixing, pressing, printing, art, etc. The musician who is buying the package pays for the sidemen though Rusty often (as in Grove’s case) sets up the session sidemen too. He assigns master numbers, keeps records of his operation, etc.

In Bartenstein and Ellison’s book, Industrial Strength Bluegrass (Illinois, 2021), Mac McDivitt devotes a section to Jewel, saying that by 2008, when Rusty retired, “Jewel had cemented a reputation as the ‘go to’ place to record in the Cincinnati area” (53-55). Selling the business, York moved to Florida. He died in 2014. Bear Family has released two CDs of Rusty’s rockabilly recordings.

Neil V. Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, and co-chair of the IBMA Foundation’s Arnold Shultz Fund.

Photo of Rosenberg by Terri Thomson Rosenberg. All other photos by Carl Fleischhauer.

Edited by Justin Hiltner.