(Editor’s Note: Fiddler, songwriter, and creator Libby Rodenbough writes this personal essay on her friendship with and admiration for BGS Artist of the Month, Alice Gerrard, accompanied by her original photos taken for Gerrard’s new album, Sun to Sun.)

I remember first hearing Ola Belle Reed’s “Undone in Sorrow” when I was 19 or 20. I felt like a portal had been opened unto a world that had existed around me my whole life, unseen and unheard. I grew up in North Carolina going to visit my mom’s family in Madison County, along the Blue Ridge, where any of the graveyards on the mountain sides with their little mounds of clay outside my backseat window might have been the one from Ola Belle’s song.

That portal didn’t open for me in the mountains of North Carolina, though – it was in Chicago, at the Old Town School of Folk Music, an institution that had come out of the ‘50s folk revival. I was big on Pete Seeger and John Prine at that time in my life, and had found out my dad had a cousin with a spare room in Chicago, so I went on a little pilgrimage during a recess from college.

It was there that I learned my first old time fiddle tunes, belting the refrain “down in North Carolina” from “Waterbound” at the school’s open jam while the Chicago winter dumped three feet of snow outside. It was there I first learned the rudiments – very rude in my case – of clawhammer banjo. It was also there that I first heard a left hook of a song called “A Few Old Memories” by Hazel Dickens, which appeared on her 1973 duo record with Alice Gerrard, Hazel & Alice.

I went home from Chicago with new eyes and ears. Places I’d known forever became newly populated with epic figures, recast in the light of 200-year-old narratives. My first semester back in school, I was in an introductory folklore course taught by Mike Taylor (of Hiss Golden Messenger) and he started talking about his friend Alice Gerrard, who lived a town over in Durham. I was fairly well tangled up in time and place at that point – even the deceased people I’d been learning about were brand new to me – so I had to blink a few times to digest that she was the same person singing harmony on “A Few Old Memories.”

Today, 10-ish years later, I sit with Alice in preparation for writing this piece and she tells me about driving Ola Belle Reed in her Dodge van on tours through the South in the late ‘60s. She’s my oldest friend (nearly 90), and all competition lags behind her years pretty pathetically. She also makes a lot of the people I talk to seem boring. We’re in the same business: We sing songs and play shows and make records. She’s been doing it a lot longer, and I think she knows about five times as many songs.

Hanging out with Alice helps me understand why she wanted to be friends with people like Elizabeth Cotten and Luther Davis, who were elderly when she met them. She heard the way they played and sang and had to talk to them about their lives. “They knew exactly who they were,” she says. For a young person who had moved across the country from Oregon to Washington, D.C., without maintaining much contact with home, dropped out of college, and had four children, that self-knowledge was aspirational. Though their rootedness in their communities was part of what drew her to them, she didn’t think of them as avatars of bygone primitive ways of life, or as characters in a play – they were people. Elizabeth Cotten was somewhat guarded, but over years traveling and playing together, she told Alice about indignities she had suffered as a domestic worker and as a Black female folk performer, and about subtle acts of defiance she had worked into both vocations. Luther Davis talked about how lonely it was to get old and run out of witnesses to your own life.

Alice is likewise unafraid of being a person. She’ll tell you straightforwardly that she was unprepared to be a mother, that it was essentially impossible to pursue a music career – which was something she knew she wanted for herself – and still give adequate time to her kids. We commiserate about music industry bullshit and engage in light shit-talking about the idea of showmanship.

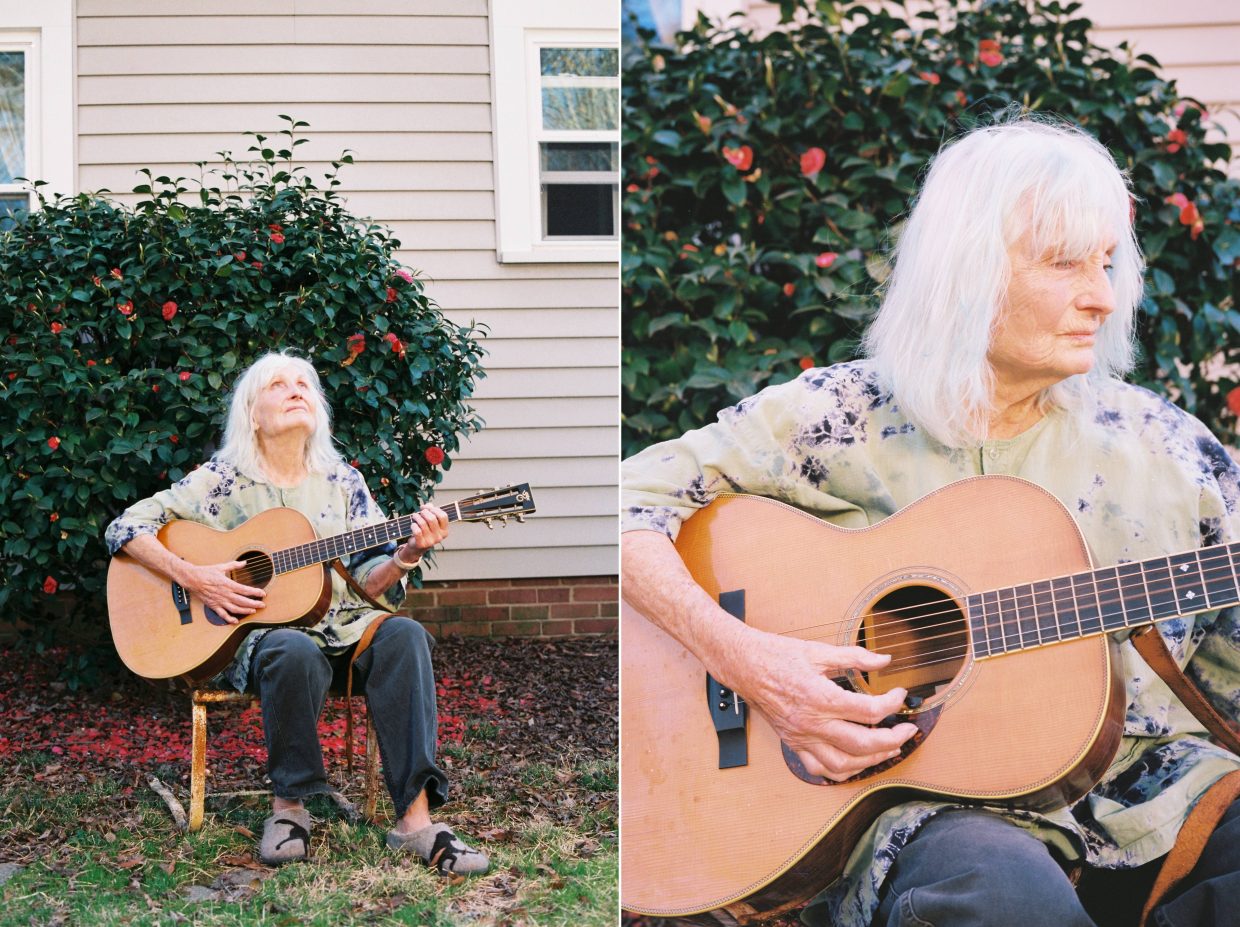

She’s usually wearing one of her collection of t-shirts that pertain to her dog Polly’s agility training facility (“Fast and Furryous”). This past March, when I took these photos of her to use for promotion of her new album, Sun to Sun, we went through her closet together and dug out some gems, including a bedazzled commemorative t-shirt from Obama’s inauguration.

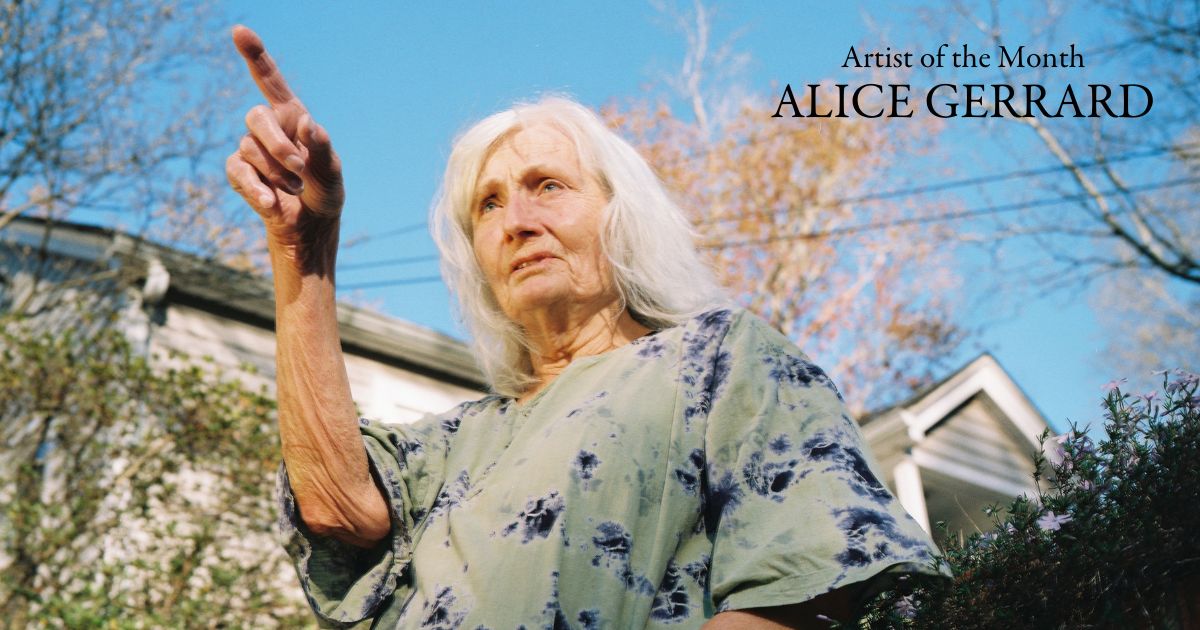

I have no training in photography – I shoot film because I enjoy the feeling of not really knowing how it works. We went to Duke Gardens in Durham, where we both live, on a week when the cherry trees had popcorned into glory. Alice looks radiant in the halo of those glowing blooms. But I also love the photos where she’s at home, standing in front of the brick retaining wall around her front yard, before she realized she still had her Apple Watch on. The sky was so blue that day, her white hair incandescent. She looks like she knows something you don’t, but in a warm way, like she knows you’ll get it eventually.

Alice is unafraid to treat a song like it can handle a little handling. She knows that songs are alive and she’s interested in being a part of their lives, not their memorialization. She smiles talking about how, in an old John Cohen film, the Madison County ballad singer Dillard Chandler starts a song in a key around here (she holds her hand at her waistline) and ends it here (she raises her hand up level with her temple). She’s delighted by the particularity of the human touch. She prefers singing voices with a bit of weirdness over purely pretty ones. Talking about Carter Stanley’s high whine, she says, “Whatever was eating on him from the inside, it was showing up in the way he sang. Nina Simone, the same way.” She tells me what a struggle it is to teach that kind of feeling to people accustomed to singing prettily. “If you’re trying to get somebody out of the soft, breathy voice, you say, ‘Look, your kid is running out into the street and you have to call your kid back.’ You don’t say,” — she coos — “‘Heyyyyy Brian, get back here.’ You say, ‘BRIAN! GET BACK HERE!’”

Whenever I’ve played music with her, Alice seems to lean into what people at the Old Town School liked – actually, loved – to call “the folk process;” she lets arrangements evolve as the spirit of the universe sees fit. I’m lucky she’s not a stickler for tradition, even traditions she could write encyclopedias about, because my fiddling style is distinctly unmoored. I was a half-rate Suzuki classical violin student growing up and then at the Old Town School I learned how to accompany folk singers on songs with three or fewer chords. I came home and started going to the old-time jam at Nightlight Bar & Club in Chapel Hill, where the jam leaders were American Studies PhD candidates who also grew up learning fiddle tunes from their hometown octogenarians. Some of my friends started a band called Mipso that was flirtatious with bluegrass and asked me to join, but I told them up front I didn’t know any licks. (They didn’t seem bothered by that.) I’ve since learned a few licks, and I would rather play an old time tune any day of the week than do almost anything else, but I never could sit still long enough to do what Alice calls “holding the line” — keeping and caring for the tradition.

I’m indebted to, and grateful in my heart for, people who do that work. I may roll my eyes at gatekeeping, but it’s more than wide-eyed would-be fiddle players at the gate; it’s the whole monster of monolithic, capitalist cultural imperialism, chomping down on everything small or strange. Songs can, and do, disappear, like cultures and forests, and not just by inertia but by clear-cutting. A lot of days I feel self-conscious about whatever it is I’m doing instead of holding that line. When I listen to Alice tell stories about the many singers and players she’s known over the years, though, I remind myself that they each have a distinct relationship with tradition – and with what it means to be an artist.

For a long time there’s been a divide, rhetorical and sometimes actual, between “the folk” and “the folkies,” which maybe means country people versus city people, or maybe people who grew up in a given musical tradition versus those who came to it later. Alice and I both fall into the latter category, though she’s had considerably sharper focus since her initiation. I’d rather replay a 10-second clip of a Mark O’Connor fiddle solo at one-quarter speed forty-seven times in a row than try to examine that dichotomy in any more detail at this moment, but I did spend a lot of my undergraduate days thinking about authenticity and who’s entitled to do what with old songs. Alice has often found herself among people who look at it from an academic angle – her ex-husband, Mike Seeger, came from a folklorist family – but her view remains that the compulsion to define and categorize is basically academia trying to justify itself. I don’t take that as bitter or glib, I just think she hasn’t found it necessary, in her personal relationship with the music she loves, to try to determine who gets to claim it. Or maybe, for Alice, the claim is in the singing. Talking about what makes a voice “authentic” (a word that sends a chill down my spine), she paraphrases Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart from 1967 in his definition of pornography: “I know it when I see it.”

As we clink the ice around our $7 decaf specialty iced lattes, Alice tells me about a song she’d just heard, a haunting falsetto voice with nylon string guitar, in the opening scene of Pedro Almodóvar’s new short film, Strange Way of Life. After some Google sleuthing, she identified it as a recording by the Brazilian artist Caetano Veloso (in fact, the movie is named for it – “Estranha Forma de Vida.”) She’s head over heels for this song, itching to go home and dig into Veloso’s catalog. If they ever meet, I know she will have great questions for him, the type of questions that make a person believe songs must do real work in this world.

I ask her if she thinks of her music as having “a purpose.” “Not really,” she says. But she goes on, “I want people to hear what I hear in this music.”

In my view, that’s an altruistic goal, because it’s clear that whatever it is Alice hears in the music, it gives her life its very marrow. I admire the decades she has devoted to learning and documenting traditional music, but what I aspire to most is the way she still loves a song — viscerally, instinctively, with gusto. That’s what makes a line worth holding.

“There was something about the music, the quality of the voices,” she says, recalling first hearing Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. “There’s so much beauty in it, it’s like, God, yeah.”

I had that “yeah” moment when I heard “Undone in Sorrow” and “A Few Old Memories” – and now, Sun to Sun. I hope to be saying “yeah” like that about songs for the rest of my life.

All photos: Libby Rodenbough