What does “home” mean?

Answering this question became one of the main themes in my lyrics over the last several years – especially on my new album, Anything At All. After touring consistently for the first 15-20 years of my music career, I finally bought a house in South Philadelphia. Ten years later, my family and I relocated to my hometown, Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Before moving back to Lancaster, most of the places I lived felt kind of like a coat rack. Sure, most of my belongings were there, but I knew I’d be traveling again soon – things that felt centering or “home-like” to me existed outside of the confines of a space.

My current life is a lot different than that time. Now I am a husband, a dad of two young kids, a carpenter, and a part of my local community. I spend a lot of time trying to build a comfortable and consistent home life for myself and my family. My idea of what a home means is changing yet again. I’ve compiled a few songs that encompass the various meanings of “home” to me. – Denison Witmer

“Homesick” – Kings of Convenience

I think this is one of the best opening tracks on any album. The way the two guitars immediately start walking down the scale is captivating. My favorite lyrics are the last few: “A song for someone who needs somewhere to long for/ Homesick because I no longer know where home is…” It makes me think about the many days I’ve spent in headphones traveling in trains or tour vans, leaning my head against the window and listening to music that made me feel at home.

“Rene And Georgette Magritte With Their Dog After The War” (Original Acoustic Demo) – Paul Simon

I put this song on almost every mix I make. This is Paul Simon at his finest – just him and a guitar. In this story we follow Rene and Georgette Magritte as they reflect on the differences between their time in New York City and their lives in Europe during WWII. Ordinary moments like opening dresser drawers or window-shopping trigger memories of home.

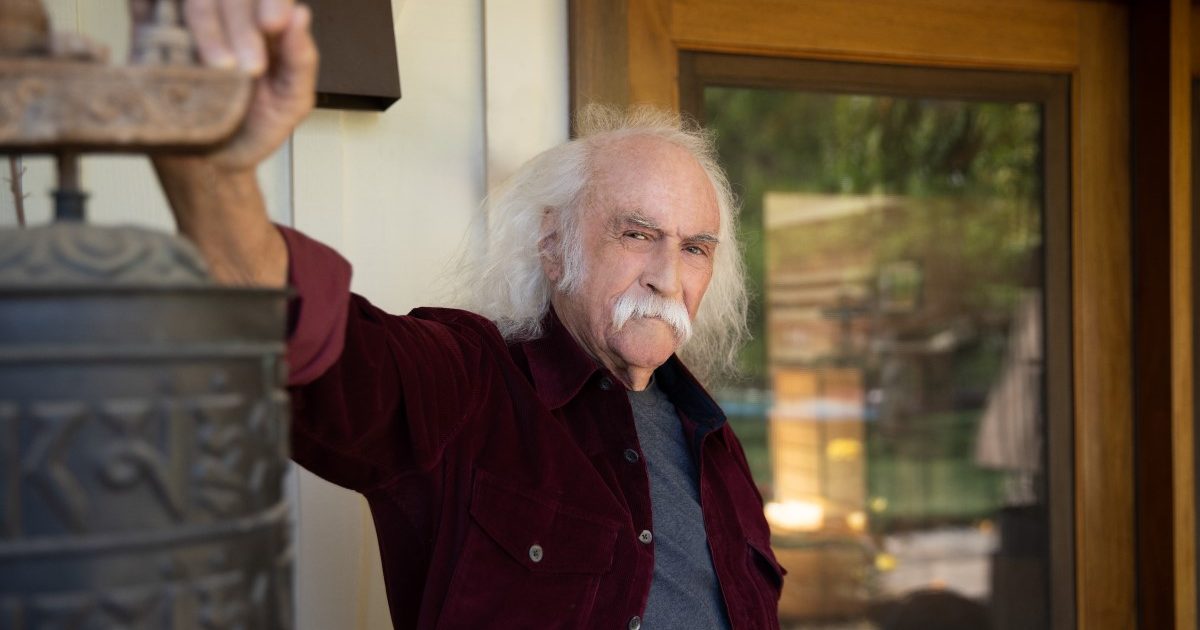

“Just A Song Before I Go” – Crosby, Stills, & Nash

Starting with a crash cymbal and leading right into a fuzzy guitar riff, this song has an instant warm vibe. I’ve always loved the way Graham Nash leans into writing about his life as a musician/songwriter. There’s a risk that it might not be relatable to a wider audience, yet he always finds a way to make the feeling universal. The lyrics “When the shows were over/ We had to get back home/ When we opened up the door/ I had to be alone…” connect deeply with me.

There were a lot of times on tour that I felt like I was turning into a ghost – passing through towns and people with no real sense of deeper connection or longevity. No real sense of home. Sometimes weeks would pass with mostly small talk and I would lose sight of who I was. Finally getting home, dropping my bags, closing a door behind me, and spending a week alone in silence was just what I needed to recoup.

“In Tall Buildings” (Live) – Gillian Welch

A lovely song written about returning to and centering your life around the things that really matter to you. I love the lyrics “When I’m retired/ My life is my own/ I made all the payments/ It’s time to go home/ And wonder what happened/ Betwixt and between/ When I went to work in tall buildings.” It’s a beautiful reflection on the things that we leave behind either knowingly or unknowingly when we get swept up in the paths our lives take. Gillian Welch’s vocal delivery is always beautiful. The way she can take any song and filter it through her own style with honesty and sincerity is incredible.

“A House With” – Denison Witmer

Yes, adding one of my own songs here. It fits with the theme. Mid-COVID lockdown, my wife and I got really into two things: birding and plants. We did everything we could to get birds to visit our yard. We did everything we could to green the outside and inside of our house. This led to hanging bird feeders all over the place and planting everything from shrubs to trees to lots (and I mean lots) of indoor plants.

This song started as kind of a joke. I often walk around my house playing a small classical guitar and making up goofy songs to make my wife and kids laugh. This song started that way — I was watching the birds on our feeder and naming them as I saw them, then I went from room to room naming the plants we have in our window sills. I recorded an iPhone voice memo and forgot about it. I’m not sure what motivated me to share it with Sufjan (who produced my new album and this track), but I think it was because I knew he is a fan of concrete nouns and words that are interesting phonetically. He ended up choosing this from the batch of demos I presented to him. I am glad he did, because it’s one of my favorite songs on the album.

Sufjan didn’t like the original lyrics of the last verse… I remember him saying, “In the first two verses you are telling us what you are doing and how it fills your heart, but you never tell us why. You should try to answer that question for yourself.” I rewrote the ending and it was at that moment that things clicked into place for me.

“Take Me Home, Country Roads” – John Denver

You can’t really go wrong with the earnest nature of John Denver. I love the lilting quality of this song – lyrics about longing juxtaposed against the happy upbeat sound. It’s a love song to a place. I have a lot of respect for John Denver, because he was always unapologetically himself. He talked about how he wanted to not just entertain people, but also touch them. I think he understood the magic of music and connection. Listening to John Denver also makes me think about my dad because he was his favorite musician.

Photo Credit: Lindsay Elliott